Life in Prison for Hemp

José Peña brought some roadside weeds home from Kansas. Cops decided it was reefer, and a Texas court sentenced him to life in prison – without the evidence. It took a decade for Peña to get back some of the pieces of his life.

By Jordan Smith, Fri., March 16, 2012

(Page 2 of 3)

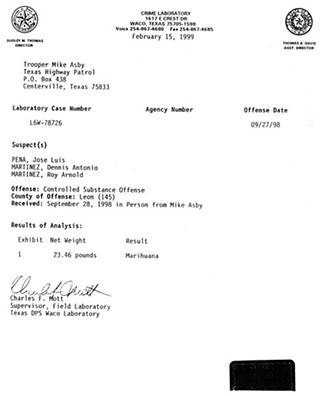

On the ride into Centerville, Peña says he implored Asby to have the plants tested – that would prove that they weren't drugs, he said. Asby, who'd loaded the plants into a blue plastic storage tub before storing them in his trunk, assured Peña that the state would test the plants to determine whether they contained any tetrahydrocannabinol (aka "THC"), the main psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, the chemical indicator that a plant is indeed pot. Asby took the plants to Waco the next morning, where he handed them off to Charles Mott, then a 37-year veteran employee of DPS' Waco lab, who testified in court that he was the one who tested the plants. But that, as it turns out, was about as much as he remembered about the case. Indeed, in March 2000, almost three years before the case went to trial (why it took nearly four years to prosecute Peña is unclear), the Waco DPS lab completely destroyed all the evidence. Moreover, Mott testified, the original file with detailed documentation of testing procedures and results – including how the sampling and analysis had been performed – was also missing. By the time of Peña's trial, the only thing that remained was a one-page printout from a file that says the "results of analysis" reflected more than 23 pounds of marijuana – though how that was determined, or how much THC (if any) was found, will be forever unknown.

Village Idiots

Why the evidence was destroyed is uncertain; Mott said he received a legal order – from Asby, he recalled – directing him to destroy the evidence. But because the file was missing, he admitted, he did not even have a copy of the destruction order; all that remained was a computer notation that the order had been received.

Asby said he did not send any such order to the lab – and although Mott said the lab often took direction to destroy evidence directly from police officers, such a procedure should not have been proper. By state law, a judge must issue an order to destroy evidence, sometimes at the behest of a district attorney, says former D.A. Ray Montgomery, who led the Peña prosecution. In the Peña case, Judge Kenneth Keeling and Montgomery each averred on the record in court that the destruction order did not come from either of them. "You can't do that legally, as I understand, without a court order, and they didn't have a court order," Montgomery, now retired, recalls. "Sure, it's troubling to me that the law would not be followed," he continued. "I don't know why in the hell the DPS destroyed it," but, he reiterates, that order did not come from anyone at his office. "We'd be absolutely the village idiot to ask a judge to destroy evidence in a pending case."

The destruction of evidence made it difficult, at best, to mount a defense – and Peña's trial attorney, Brent Cahill, objected several times, arguing that to go forward without access to evidence (for which the defense had received court permission to have tested by an independent lab before the destruction was discovered) would violate any number of Peña's rights – including his confrontation and due process rights under the U.S. Constitution, as well as his "due course of law" right under the Texas Constitution. Keeling was not impressed; as he saw it, there was nothing to suggest that the destroyed evidence would have been favorable to Peña's case – even if it had been subjected to additional testing – so he allowed the trial to move forward with only the testimony of Asby and Mott to confirm that the plants were what the state said they were.

That was apparently fine with Mott, who said the destruction of the evidence was a random error and his lab generally did not make mistakes. "Has your office ever made a mistake?" Cahill asked Mott.

"We are human; we probably have," Mott replied. "A reportable mistake, a mistake that affects analysis, no."

"Never made a mistake in analysis?" Cahill asked.

"That was reported, no, sir," Mott said.

Mistakes Happen

That assurance was apparently sufficient to convince the jurors that Peña was guilty – a decision they reached before 6pm on the same day as the trial. After a short punishment hearing the following day – at which prosecutors trotted out Peña's prior convictions, including drug possession – the jury imposed his sentence: life in prison plus a $10,000 fine.

That Asby was able to determine (by appearance or smell) that the plants were pot, or that Mott's lab had never before improperly destroyed evidence nor ever made an error in analysis – is highly unlikely. Indeed, contemporaneous to the Peña trial, the Houston Police Department's crime lab was at the center of a growing public scandal involving contaminated samples, files in disorder, even a roof leaking into an area where biological samples were stored. The city of Houston is considering whether to move the lab out from underneath the HPD umbrella in order to give it more independence – a recommendation applicable to labs across the nation that was among many made by a panel from the National Academy of Sciences in its groundbreaking 2009 report on the national state of forensic science. In a sweeping investigation of lab practices across the country, the Denver Post in 2007 found that in the 10 states they investigated, biological evidence had been destroyed – or "purged" – in nearly 6,000 unsolved rape and murder cases, "rendering them virtually unsolvable."

"You can't keep everything," Arthur Morrell, clerk of a New Orleans criminal court, told the daily.

In creating the Forensic Science Commission in 2005, Texas lawmakers acknowledged the need for better oversight of forensic labs. Among the questions currently on the commission's plate is an allegation that APD's crime lab has been inaccurately conducting analyses of suspected drugs in criminal cases; the APD has denied any wrongdoing.

Show Malice

Concerns of this sort were among those noted by a two-judge majority of a three-judge panel of the 10th Court of Appeals, which concluded in 2005 that Peña's conviction should be overturned and the case returned to Leon County for retrial or dismissal. "[T]he recent findings of negligence in the handling of evidence by crime labs across the country, resulting in hesitation and concern for those individuals whose convictions were connected with the work of those labs, demands that courts exercise caution when analyzing lost or destroyed evidence," the majority wrote in April 2005. "It is also clear that the negligence found in crime labs in Texas has resulted in the incarceration of innocent citizens and convictions based on faulty evidence."

Theoretically, one or the other outcome – retrial or dismissal – should have happened that year. Instead, the appellate court's opinion touched off a six-year volley between the 10th Court of Appeals and the state's highest criminal court, the Court of Criminal Appeals. At issue was the way the intermediate appeals court overturned Peña's conviction. Specifically, the 10th Court in Waco ruled that the Texas Constitution's "due course of law" provision – which is similar to but contextually different from the U.S. Constitution's 14th Amendment due process clause – provides more protection to individuals than does the U.S. Constitution. The court rejected the so-called "Youngblood standard" devised by the U.S. Supreme Court in a 1988 case (Arizona v. Youngblood) as a means of determining the limits of the accused's rights when evidence is destroyed. Texas, the 10th Court concluded, should not follow a standard that does not comport with protections afforded by its own Constitution. "Whether in cases involving contraband or those containing DNA evidence ... science is becoming increasingly capable of answering life or death questions with the alacrity of Caesar's thumb," the court concluded. "As a result, it is imperative that we consider the loss or destruction of evidence carefully. ... [W]e join our sister states in rejecting Youngblood as persuasive when interpreting the due course clause of the Texas Constitution."

The Youngblood standard had in fact failed to protect Larry Youngblood from being incarcerated for a crime he did not commit. Youngblood was tried and convicted of abducting and sexually assaulting a 10-year-old boy who identified him in a lineup, but DNA testing was inconclusive, and the boy's clothing had not been properly refrigerated by police, destroying the evidence. Youngblood was subsequently convicted based on the boy's eyewitness identification. When Youngblood appealed, the U.S. Supreme Court eventually ruled that a defendant must show not only that the evidence destroyed would likely have been favorable to the defense, but also that the destruction was done maliciously. "Unless a criminal defendant can show bad faith on the part of the police," said the court, "failure to preserve potentially useful evidence does not constitute a denial of due process of law."

In 2000, after updated retesting of the DNA evidence revealed he was not the boy's assailant, Youngblood was exonerated, and the Youngblood standard has since been harshly criticized; numerous states have since rejected it as not comporting with protections afforded by their state constitutions, including its shifting the burden of proof from the state to the defendant. "The Youngblood bad faith requirement has posed a virtually insurmountable burden on defendants seeking to demonstrate that the government's destruction of evidence violated due process," American University Washington College of Law Professor Cynthia Jones wrote in the Fordham Law Review in 2009. Jones says that it's nearly impossible to find a case that would be overturned based on the Youngblood standard – clearly it didn't help Youngblood, who was actually innocent. "What better proof of the fact that this is not a good idea?" she asked in a recent conversation.

At trial, Peña's defense attorney noted the burden that the Youngblood standard placed on his client to have to refute the "expert" testimony of Asby and Mott, who – though lacking actual evidence – claimed definitively that what Peña was transporting in the fall of 1998 was marijuana. "I understand the court is going to let this testimony in, that this was tested as marijuana, that it was marijuana ... and when the Court [ruled] that [the evidence destruction] wasn't done purposely by the laboratory, be it the state of Texas, that puts defense counsel in a posture, Judge, where we are forced to assume the burden and prove a negative," Cahill told Keeling.

"I know that, Mr. Cahill. But you know, I didn't write the law," Keeling replied. "I realize it puts the defendant in a predicament," he continued. "I have got to follow the law that the courts write for me, and that's what I'm trying to do and that's what they told me to do, so I'm doing it."

Dueling Judges

Other states – among them Alabama, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Tennessee – have rejected the Supreme Court decision in Youngblood, but that had not happened in Texas – until Peña's case made it to the 10th Court in 2005. Ruling in Peña's favor, the appellate court recognized the impossible burden the federal decision placed on defendants and ruled that a different and more equitable balancing is required to satisfy the Texas Constitution. "One of the many reasons promulgated for a rejection of Youngblood is the practical impossibility of proving bad faith on the part of the police," the majority wrote. As such, the court reasoned, the best approach to handling the impact of lost or destroyed evidence is to consider three things: First, "the degree of negligence involved"; second, the "significance" of the destroyed evidence; third, the sufficiency of remaining evidence "to support the conviction."

"If after considering these factors," continued the ruling, "the trial court concludes that a trial without the missing evidence would be fundamentally unfair, the court may then determine the appropriate measures needed to protect the defendant's rights" – either by crafting an instruction that the jury must construe the destroyed evidence as favorable to the defense (such as is done in Texas civil cases, where jurors are told to assume destroyed evidence would negatively affect the position of the party responsible for the destruction) or by dismissing the charges.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.