Niche Justice

Travis County specialty courts try to break the cycle of crime

By Jordan Smith, Fri., March 26, 2010

For Kellie R., it started with a quaalude.

She'd first taken the drug while on a double date when she was 15. She'd been a shy child, and on the date, even trying to make small talk with her older and more gregarious sister was unbearable. That is, until she took the pill. "Within 15 minutes of taking that quaalude, everything changed," she recalled recently. "I stopped shaking; I could talk. It made everything all right. I thought, 'Oh my God, there is hope.'"

That was the first moment of what would end up becoming more than 20 years of addiction to opiates. Kellie eventually became a heroin addict and, at her lowest point, was shooting up with OxyContin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. She lost her job as a bank executive and burned through her entire savings.

Eventually, it got so bad that she didn't leave her Northwest Austin home except to meet her dealer; several times she overdosed and was hospitalized. Her then-husband, also an addict, would get paranoid when he was high and more than once called the cops to their home. Between those calls, the calls for ambulances, and the calls from neighbors, it wasn't long before the Austin Police Department was watching. In retrospect, she says, she knows the cops thought they were dealing. They weren't, but they were spiraling downward fast.

Amazingly, Kellie had never been in serious trouble with the law (only a single paraphernalia charge) until about 5am on April 29, 2005, when the APD SWAT team burst into her home tossing flash-bang grenades. They tore the house apart and hauled Kellie off to jail and her husband, who had abscesses on his legs almost to the bone, off to the hospital (and eventually to jail). "I knew I was in big trouble," she said.

Kellie bonded out two days later, and the attorney her husband had contacted gave her information about Travis County's drug court program. "He kept saying, 'This is what you need to do.'" Kellie went home "dope-sick" and looking to score. "I thought I knew what I needed. I thought the problem was heroin. I didn't understand that wasn't the problem at all." She considered the drug court program. If she successfully completed it, the felony drug charge hanging over her head could be dismissed, her record wiped clean. But she wasn't ready. They wanted her to move into a halfway house; she thought that was too drastic.

She went to an inpatient rehab in the Hill Country, came home, and relapsed. It wasn't until Labor Day weekend 2005 that Kellie had a breakthrough. "I had a moment of clarity. ... 'Get yourself into that program, because [you're not going to get clean] any other way.'" She returned to drug court and told the judge, Joel Bennett, she was ready. "I was willing to do whatever it takes," she said. "I'd pretty much caused them to shut the door on me." Bennett said she could get into the program, but first she'd have to spend two months in the Del Valle jail, participating in a cognitive program that would keep her clean. She was the first participant in the program's 17-year history to be sent first to jail.

It worked. "I went in with three weeks sober" and completed the program in one year. She's been sober for more than four years and now leads group counseling sessions for other women trying to get clean. "I needed the accountability. I needed the structure," the now-52-year-old said. "I realized it is a matter of life or death for me."

Changing Human Behavior

The creation in 1993 of the county's drug court program – which gives defendants a chance to get sober, change their lives, and clear their criminal records – was at the forefront of a now national trend. Nationally, criminal justice professionals have been trying to establish a different way of doing business, with an emphasis on addressing the root causes of criminal behavior. This has led to the creation of numerous "specialty courts" – also called "problem-solving" or "therapeutic" courts. According to the National Drug Court Institute, as of December 2007, there were more than 3,200 specialty courts at work across the country. More than half are drug courts, the first wave in the nationwide movement toward therapeutic justice.

For years, the system has worked under the assumption that time in jail or prison is what corrects criminal behavior – and the more time spent inside, the better. In that perspective, 10 days is good, 10 months is better, and "10 years is the best of all," says David Grassbaugh, a criminal defense attorney who has worked in the county's drug court, one of the country's oldest, for 14 years. "And that's just false." The U.S. has the highest rate of incarceration in the world, with more than one in 100 adults in jail or prison and more than 7 million people on probation.

The criminal justice system is designed to operate on a strictly rational basis, says Grassbaugh. That's certainly necessary to deal with crime and criminals in an orderly and predictable way, but it isn't so good at changing behavior – yet changing behavior is the only way to deal effectively with crime. "We need a rational structure," Grassbaugh says, "but also we have to realize that the object of this system is not to deal with rational behavior; it is to deal with human behavior." That is at the heart of the specialty courts movement, which has taken a firm hold in Travis County. The county joined the movement with the creation of its drug court (the second oldest in the state, after the Jefferson County court established just four months earlier, in April 1993) and since then has steadily increased the number and type of specialty courts.

Currently, there are 10 such courts operating here – more than in any other county in Texas – including adult and juvenile drug courts, DWI court, felony and misdemeanor mental health courts, a family violence court, Project Recovery (a program for "chronic inebriants," as County Court at Law No. 5 Judge Nancy Hohengarten describes it), and soon, a veterans' court (see "And Now Veterans: 'We Owe Them'"). The ultimate goal of these programs is simple: Create a framework that addresses and corrects underlying behavioral issues so that as many people as possible can be diverted from jail and prison – and can be kept from becoming repeat customers of the criminal justice system. "These are driven by [the question], 'What causes crime?'" says County Attorney David Escamilla. "And if we avoid recidivism, we succeed."

The programs are not without their critics (though in Austin there are surprisingly few). Problem-solving courts operate in a collaborative environment in which prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, probation officers, and social service providers work together to resolve individual cases. The approach has raised concerns within the defense bar and particularly with the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers; in September 2009, the NACDL released a somewhat critical review of specialty courts. A central question is whether diluting the adversarial process weakens legal protections afforded to defendants. There are also broader questions about whether the courts should be addressing social issues at all and whether carving out special courts, each of which can only handle a limited number of cases, is in some way discriminatory or inequitable.

And more directly: Do specialty courts work?

Welcome to Drug Court

It's just before 6pm on a Wednesday evening, and more than 60 participants in the county's drug court program (formally known as Systems of Health Options for Release and Transition, or SHORT) are arriving at an auxiliary courthouse just off South Congress Avenue. They're a strikingly diverse group: men and women, young and old, brown and black and white, well-dressed and not so well. There are professionals alongside blue-collar workers, students, some unemployed. They all have at least two things in common: They've been arrested and charged (most more than once) with felony drug possession, and they are potentially facing up to 10 years in prison if convicted. And with that comes collateral damage: Having a felony record will make it harder to get a job and can foreclose the ability to receive student loans or to get access to public (or other) housing.

The people gathered here have been given a chance to avoid a conviction altogether. If they successfully complete the terms of the drug court program – intensive outpatient drug treatment (or for severe cases, inpatient), random drug testing, counseling, group therapy sessions, a prescribed number of 12-step meetings, and possibly other individual requirements – they could have the charge dismissed and their record expunged. The program requires at least a one-year commitment, $1,000 in fees paid to the county, and at least six consecutive months of sobriety before graduation.

In other words, it is not a simple get-out-of-jail-free card; rather, it is designed specifically to lead people to a new, sober life. "My goal is to turn out a healthy human being loose on society," says Judge Joel Bennett, who has been presiding over this court since its creation in 1993, making him the longest-serving drug court judge in the country. "All we're trying to do is bring to bear resources on people's problems to solve them, to bring them back to health, as taxpayers."

When everyone is assembled, Bennett strides into the room in his black robe and assumes the bench. The participants, each in different phases of the program, are called one by one to the bench. They show their 12-step cards to document their attendance at meetings. "Let's give him a round of applause," Bennett says of one man. "He's doing a good job." Everyone claps. Even those who have not done as well – they've missed meetings or failed to show up for a drug test – are met with encouragement.

But there are also consequences for noncompliance, ranging from being ordered to complete community service to spending a weekend in jail. On one Wednesday evening, a graduating participant is asked to share with the group what he's learned. He's learned to come out of the darkness and to live in the light, he says. He's left behind a life that was getting him nowhere except into trouble and is now on the other side. He's working and in school. And he's committed to remaining drug-free. His eyes light up as he shares his experience with the group; his is exactly the kind of outcome that drug courts strive to produce.

The Weakest Links

The very first drug court opened in Miami in 1989, in response to the city's growing reputation as the cocaine capital of the world; from 1985 to 1989, drug possession arrests there increased by 93%, and 73% of defendants charged with felony crimes tested positive for cocaine use. The system was overwhelmed, and a revolving door of justice became the norm. "We all go to the window, wave goodbye, and say, 'Come back and see us again soon,' and you don't disappoint," Tim Murray, executive director of the Pretrial Justice Institute, told NACDL for its 2009 report. "You do come back and come back and come back." The notion was that getting people off drugs would keep them from becoming repeat offenders, which would naturally ease prison and jail overcrowding and realize cost savings.

The program quickly took off. By 1993, the year Austin's drug court started, there were already 19 in operation across the country, and that number has increased each year to more than 2,000 today. Retired District Judge Jon Wisser was instrumental in starting Austin's drug court. "The program was prompted by seeing lots of young black males in court who were there for minor drug charges, many of them crack charges," he said. "It was getting to where there were all of these young black males on paper with the system, and this was an attempt to stop that trend."

Wisser isn't sure that initial model worked so well. "The commitment to the program, at least a year, meant a lot of folks in the target group we were trying to get into the program weren't interested," he said. "They see that commitment to be much less appealing than to take a shorter sentence and be done with the thing." The initial structure might not have worked as planned, but the program has developed into an invaluable tool to help individuals with serious drug problems get clean, says Bennett – himself a recovering alcoholic, 23 years sober.

Wisser's observations mirror concerns raised in the recent report from the national defense bar: Drug court programs can be made to look successful by "skimming" easy cases, accepting only defendants likely to be successful (perhaps even those without serious drug problems), who in turn provide the program with a high graduation rate and low recidivism numbers. That is not an issue in Austin, insists Bennett.

"We can design a program with a 100 percent success rate, but do you have an effect on the crime rate when you do that?" he asked recently over lunch in an Eastside sandwich shop. "We focus on people with very severe problems" – people with "chronic relationship problems, who are chronically undereducated; some haven't worked in years," he continued. "These are the weaker links in the chain of our society." And getting them well saves a lot of money, he says, not only in prison costs but also in health-system costs and larger social and familial costs: "When you're able to have a drug-free baby, I can't put a value on that," he said. "We teach them how to be parents, so now instead of the state raising their kids, they can raise their kids."

As if on cue, a young man leaving the restaurant stops to ask Bennett if he's still "showing people the way." Yes, Bennett replies. The man tells the judge that he's been employed by the same company for some 20 years now and has continued to live a clean life. He thanks Bennett and leaves the shop. Another drug-court success story, Bennett says.

By the numbers, Austin's drug court has been fairly successful. Since Jan. 1, 1993, there have been 2,846 participants; 1,477 have graduated. According to the county, the recidivism rate among graduates from 2005 to 2006 was 27%, compared to 50% for similarly situated defendants whose cases traveled through the traditional system. "Other courts would not be trying [these approaches to criminal justice] if they didn't see the value in this," Bennett says.

Take a Number

The Travis County drug court led by Bennett has been a "visionary program" with national influence, says Caroline S. Cooper of the Justice Programs Office of the School of Public Affairs at American University. There's no doubt that in Austin it has led county officials – including elected prosecutors and judges – to create additional problem-solving courts. The success of Bennett's court certainly influenced County Court at Law No. 7 Judge Elisabeth Earle, who presides over the nearly 2-year-old DWI court, which is patterned on the drug court. Earle's court team – including a dedicated probation officer, substance abuse counselors from Cornerstone Counseling, an assistant county attorney assigned to the court, and two private-practice defense attorneys paid to provide counsel to the 56 people presently on the court's docket – meets once a week to discuss the progress of the court's "clients." Some are doing well, progressing through the three phases of the program and apparently on-target to graduate at the end of the minimum year commitment. (The DWI program requires an initial period of intensive outpatient treatment lasting roughly 13 weeks, followed by another 39 weeks of "intensive" aftercare and "supportive" aftercare.) Like drug court, relapses or other failings are treated with both encouragement and graduated sanctions.

As in the drug-court model, the target population for DWI court is people with serious "impairments," says Judge Leon Grizzard, a veteran defense attorney who has worked as a drug court defense attorney, a DWI court defense attorney, the relief judge for drug court, and is also the county's magistrate judge. "The people that [Earle] is getting into that program, if you look at their assessments, are very impaired people. It would curl your hair [to know] how hard their substance abuse problems are," he said. "They're not as crime-prone [as those in drug court], but they're at high risk for committing other [DWI] offenses – these are the people going the wrong way on the interstate. ... They're very impaired in their lives." Indeed, DWI court participants must already have one DWI conviction and have picked up at least a second DWI arrest within two years – but, as in drug court, in order to qualify for the program, defendants can have no other "unresolved" criminal cases pending or any truly violent criminal history. Cases are first screened for appropriateness by prosecutors, but judges retain some ability to allow defendants into the program over prosecutors' objections.

Unlike drug court, DWI court is a "post-plea" court: State law will not allow DWI charges to be dismissed, so defendants must first plead "no contest" in order to be accepted into the program. But successful participants can avoid jail time, get sober, and retain the right (albeit limited) to drive. "The carrot" in DWI court, says defense attorney Bradley Hargis, "is that you're not getting hit by more sticks." Cornerstone counselor Kate Bailey says she believes the DWI court is a success; participants are required to do more treatment than is typically offered in regular outpatient treatment (three months in DWI court with 87 hours of aftercare vs. six weeks in a regular outpatient program with just 52 hours of aftercare). More time means a greater chance at change. "I love the program," she said. "The longer the treatment goes, the more time it has to set in. [The program offers] accountability, respect, and support."

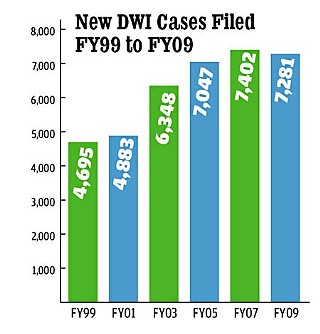

As in drug court, there is limited enrollment in the DWI program. According to Travis County, the number of DWI cases has increased 55% since fiscal year 1999, with more than 7,281 cases filed in fiscal year 2009; as of last June, 501 persons had two or more DWI charges pending. Currently, says Hargis, there are 300 cases pending that meet the minimum legal requirements for acceptance to DWI court. Twenty candidates have been preapproved for the program and are awaiting a slot, says Earle, and 90 more are in the wings, waiting on an assessment to see if they meet the more subjective requirements for acceptance, including a determination of their level of impairment, level of honesty about their problems, and level of motivation to make life changes.

Inevitably, demand is outpacing the available spaces in the DWI court, which is funded by a roughly $245,000 grant from the Governor's Office. And while there have not yet been any studies done regarding the success of the relatively new program, nor any comparative recidivism numbers, the basic numbers collected by the program staff are encouraging. Of the 87 people who have started the process, only 11 have dropped out. To date, 21 have graduated, and among that group none has been rearrested.

Casualties in the War

Overall, the specialty courts in Travis County have strong local support, though it didn't materialize overnight. Judge Mike Denton recalls the first time he observed Bennett's drug court back in the Nineties. "What the hell is this?" he thought, standing in the back of the courtroom with a cop friend. When the group applauded a program participant who'd been sober for a number of days, Denton didn't know what to think. "I'm in the back ... going: 'Son of a ... this is terrible! This isn't a court!'" he recalled recently, laughing. "But, basically, Joel [Bennett] convinced me, this is exactly right! You know, we can bring in the guy that has been busted [with drugs] and treat him the same way we treat the next guy, and we know he'll be back," he continued. "The question is: How many times do you do the same thing expecting a different result? Drug court works."

That experience was crucial to Denton's certainty that a family violence court would also work (see "Family Violence Court: 'Homicide Prevention'"). "That's not to say we don't have our detractors. When we first opened this court, I know the joke was, 'Oh, he's just opening a boutique court,'" he said. "That always stuck with me. ... It was another judge, so I'm not going to say [who], but, you know, not everybody agrees" with the increasing specialization.

There also remain detractors, most vocally among the defense bar, who express concern most specifically that the level of advocacy in a cooperative setting leaves defendants unnecessarily vulnerable to prosecutorial power. That was indeed one of the concerns that Rick Jones, co-chair of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers special task force on problem-solving courts, described in February during a symposium on criminal justice reform at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York. A defendant shouldn't have to plead guilty to get treatment, he said. "This creates huge ethical problems for defense attorneys" – under standard specialty court rules, they're effectively forced to decide whether they're working for "the team" or for the defendant. Indeed, in some of Austin's specialty courts, including DWI and Project Recovery, the price of admission is a plea to the charge. However, those pleas aren't held against defendants if they fail and have their cases tossed back into the regular system – a protection placed in writing in the case of the DWI court, which reassures clients that nothing said or revealed in DWI court can be used against them in any subsequent proceeding. And drug court, notes Bennett, is a pre-plea court, meaning that if a participant's case is kicked back to district court there is nothing hanging over his or her head. "Here, we don't lose anything," he said. "In fact, we get two bites of the pie."

Still, NACDL and some local defense attorneys argue that turning the courthouse and its judges into social service or public health providers is simply misguided. "I'm a good progressive; I believe in trying to fix things to make them better," says Austin defense attorney Skip Davis. But, he continues, "Judges make poor social workers." The money spent handling social issues in the courthouse would be better spent on front-end services that might make it less likely that these populations would actually end up in trouble with the law. That's precisely the argument articulated by NACDL in its recent report.

In the case of drug courts, the group's chief recommendation for going forward is to end the war on drugs and to treat substance abuse as a problem of public health, not primarily one of public safety. "The view from 50,000 feet of these courts ... is that [they are mostly] wrongheaded policy for the country," Jones said during a panel presentation at the John Jay symposium. "Addiction is an illness. Instead of being dropped off at the courthouse," people with substance abuse problems should be taken to public health centers. Money and resources now going to problem-solving courts, argues NACDL, would be better spent on social services.

Certainly, few Travis County officials disagree with that grander idea, says drug court Judge Bennett – but that dramatic, national change hasn't happened. "And people now expect their judges to do more than send their babies to the penitentiary."

Last Resort

The county's 2010 budget allocates more than $112 million to operate the justice system (not including law enforcement or jail operations) of which drug court is just one piece. It costs the county just more than $1 million to operate. (Most comes from general revenue, supplemented by fees paid by program participants and state grant money.) Many of the county's problem-solving courts operate primarily using state or federal grant money. In other words, the programs have not substantively increased the county's criminal justice budget. Moreover, according to the National Association of State Alcohol/Drug Abuse Directors, every dollar spent on treatment – such as in drug and DWI courts – creates $7 in future state savings, in part by reducing the reliance on jail and prison.

But even if the money were taken away from the problem-solving court projects, it almost certainly would not go to social service programs, as critics of the specialty-court movement have suggested, says Matthew Jones, a defense attorney who is one of a small number of lawyers assigned to handle cases on the county's mental health dockets. "If you take money out of the courthouse and out of the criminal justice system, it won't go to social services; it will disappear" – and it certainly won't go to helping the mentally ill, he said. "If you want to fix it, go to the Legislature and first beat your head on that wall for eight or 10 years. And then come back and talk to me about it, because they really are a wall," especially in Texas. "Their biggest concern is making people show IDs when they vote; this is their greatest concern. These are the people you want to fix your mental health system?"

This story was supported in part by a fellowship with the Harry Frank Guggenheim Foundation and the Center on Media, Crime and Justice at John Jay College.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.