Guilty Until Proven Innocent

AISD brings the hammer down

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Sept. 25, 2009

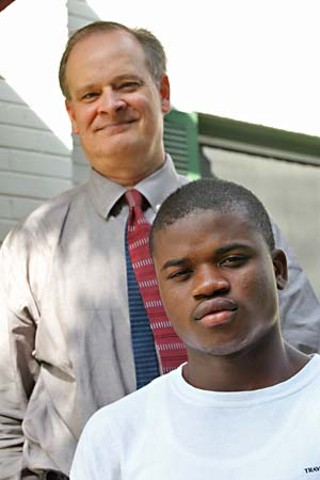

There is no dispute that something happened on the property of Kealing Middle School on the evening of July 14. And Austin Independent School District officials, the Austin Police Department, 17-year-old Eastside Memorial Green Tech High School senior Mamadee Baby Kamara, and his court-appointed lawyer, former prosecutor Rick Reed, all agree Kamara was present during the incident.

That's where the agreement ends.

A man told police he was attacked that night by a group of kids and robbed of his wallet. Kamara was later charged with aggravated robbery (one of several juveniles charged in the attack) and spent two weeks in jail before being released on a personal bond in late August. Last week, prosecutors dismissed the case against Kamara. But in the meantime, AISD officials had already expelled him over the matter – an expulsion they decided should last for 730 days, a full year longer than Kamara has left before graduating.

Still very much in dispute is Kamara's part in what happened in the park at Kealing, whether he was afforded due process before the school district kicked him out of Eastside High, and whether the district's decision will effectively destroy Kamara's chances at earning the football scholarship he had hoped would be his ticket to college.

Kamara was born in Liberia in 1992, and his family was tossed from country to country in the Nineties – from Liberia to Sierra Leone to Guinea – fleeing a chain of violent civil conflicts. Kamara, his brother, and his parents ultimately landed in a United Nations refugee camp, where they received the assistance they needed to come to the U.S. It wasn't until Kamara, now 17, arrived in Austin eight years ago that he was able to attend school full time.

Since then, he's done well. According to comments by his teachers, Kamara has been a consistent student who completes his assignments; he is helpful in the classroom, "energetic, outspoken," and has an "eagerness to learn." None reported any aggressive conduct, and there is no record of any disciplinary problems. "Mamadee's attitude and conduct were excellent," his football coach wrote, praising Kamara's leadership.

Given these positive reports, the district's August decision to expel him is puzzling and troubling. Although AISD's student discipline coordinator Andri Lyons says students are given "due process" before a decision to expel, Reed says that didn't happen in Kamara's case. "The way they have explained it to me, once the affidavit [for his arrest] was filed, that was the end of it, and it didn't much matter what additional information I provided. ... Even if the D.A. dismissed the charges, it doesn't mean that [the district] doesn't have a 'reason to believe' that Kamara committed an offense."

But in fact, there is reason to believe Kamara is innocent. On the evening of July 14, some time around 8pm, according to Kamara, he was at home with his brother at his family's apartment on Rosewood Avenue, when a friend dropped by and invited them to join him and at least six other kids walking toward Downtown. As they walked through the park next to Kealing Middle School, Kamara was talking on the phone, so he dropped back from the others.

What happened next is disputed. According to the warrant for Kamara's arrest, a man named David Carter said that he was walking through the park when a group of kids "jumped" him, beat him up, and tried to take his wallet (they returned it, he said, after discovering he had no money). Several kids told police that Kamara had been the one who chased Carter and that Kamara either tripped or tried to trip him.

Kamara himself says that he was on the phone when he looked up and saw Carter chasing one of his friends. "So I started chasing him, and I almost was about to catch him, but I couldn't stop him." He stopped running, and while he had his back turned, he says, the other kids attacked Carter.

Kamara insists that not only did he try to stop the attack, he saw the man's wallet lying nearby, picked it up, and tried to return it. According to Kamara, Carter wouldn't take it, and another kid came up and knocked the wallet from Kamara's hand. Carter finally got up and walked away, but Kamara was shaken and worried that the kids he'd been following were looking for trouble. "I was too scared to go Downtown," he said. "So I got my brother, and we went home."

Fifteen days later, police officers came to Kamara's house asking questions; he says he told the police everything that had happened. On Aug. 7, police arrested him at football practice for aggravated robbery. He spent the next two weeks in jail before being released on a personal bond.

On Aug. 25, Kamara returned to Eastside, excited to get back to school and football; instead, administrators sent him home. Kamara called Reed, who escorted him back to the campus – as a condition of his release, Kamara was required to be in school. But while Kamara had been in jail, district officials held an expulsion hearing and ordered him removed from school. Now, despite the dismissal of the charges, it is unclear when, or if, Kamara will be able to return.

According to AISD's student code of conduct, there are a handful of offenses that automatically trigger the expulsion process. Felony drug charges, felony assaults (such as aggravated robbery and assault or murder), and weapons charges are "the big three," says Lyons, and state law requires a student be expelled when any of those offenses happen on school property. While that sounds like zero tolerance, Lyons says it really isn't. "That's a misnomer," she said last week, because that characterization ignores "the due process that's afforded" to the student.

In an expulsion hearing, school and district officials consider a "number of factors" before deciding whether there is a "reason to believe" that the student committed the charged offense, a lower standard than the probable cause police need for an arrest. Expulsion decisions "really are made on a number of factors" – including the age of the student, the law in question, and the "impact on the school," Lyons said. "There are many, many factors we have to take into account, and that may include the kid's side of the story, for sure." Officials cannot comment on individual cases, but if the hearing does end in expulsion, there is an appeal process.

But did Kamara receive due process? He was in jail when the district held its expulsion hearing, so "he didn't know about it" and certainly couldn't attend, says attorney Reed. According to district documents, school officials did not call Kamara's parents about the hearing, but apparently someone sent them a letter. Reed doesn't think they ever got it – and if they did, because of a language barrier, he isn't sure they would've understood it. (Whether the district took into account Sheku and Akata Kamara's limited English proficiency is unknown.) So district officials had no opportunity to hear Kamara's account of the incident before deciding to expel him for two full school years. If that decision holds, Kamara will not be able to graduate with his friends, nor will he be able to complete his senior year of football – a decision that could place his college plans in jeopardy. Kamara says he had received letters of interest from several schools – including New Mexico State and Ohio State – that he is afraid will mean nothing if his expulsion is not overturned.

Reed, Kamara, and his parents have appealed the expulsion, but in a letter dated Sept. 10, the district's hearing officer, Brenda Hummel, wrote that although she was "impressed with the positive feedback" from Kamara's teachers, she concluded that the expulsion should be upheld. (According to the letter, Kamara could also appeal that decision within 10 business days, but Reed didn't receive the letter until Sept. 22. Whether he'll still be allowed to appeal is unknown.)

Reed says he was told that the dismissal of charges against Kamara was not to be taken into account in the appeal decision, presumably because the dismissal came after the Sept. 3 hearing was held. Reed said he is concerned that decisions in Kamara's case have been based on the charges alone – a perception enhanced by an argument AISD's general counsel made during the appeal hearing. Because his teachers described him as a class leader, Reed recalled the attorney saying, "That was all the more reason they were concerned about him going back to that school, because he might lead kids down the wrong path," he said. "I was very troubled to hear that argument made. Good things that were said about this kid are now being used to expel him."

For Kamara, there is one issue that is troubling beyond all others: "That I was not going to be able to play [football] and that I was not going to be able to go to the school that I love and that I want to graduate from."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.