McMoldy High School?

For one McCallum High student, every day is a sick day

By Nora Ankrum, Fri., July 10, 2009

When Teresa Van Deusen pulled her daughter Nika Perry permanently out of school last April – with just a month left until summer vacation – Nika had been to the emergency room five times just since spring break. The McCallum High School sophomore was vomiting, having trouble breathing, and experiencing migraines, vision problems, swollen lymph nodes, and extreme anxiety – more than the "teen normal," her mom says. Her symptoms began with the spring rains and worsened when she was at school; when she was away from school, they would dissipate. For Van Deusen, it seemed like the return of a nightmare she'd hoped her family – and the Austin Independent School District – had left behind.

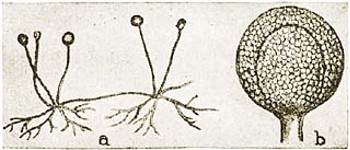

Both Van Deusen and her daughter are highly sensitive to compounds found in moldy, water-damaged buildings – specifically, Van Deusen believes, to mycotoxins produced by Stachybotrys and Aspergillus, two particularly insidious types of mold that have become somewhat infamous over the past decade for invading leaky school buildings, causing asthma and other health problems for teachers and students, and routing district dollars toward costly remediation efforts. The problem has not spared AISD. The district has devoted millions to mold remediation efforts, most famously at Hill Elementary, which had to be evacuated in 2000 because of a toxic mold invasion. The district then put together a $49.3 million health and safety bond in 2002 that earmarked $18.6 million for mold remediation projects at eight schools – but it left out Maplewood Elementary, where Nika at the time was attending second grade.

In the fall of 2001, Van Deusen noticed that her own symptoms were triggered every time she visited Maplewood. Not long after that, Nika started getting sick, too. Van Deusen complained to the school, and district testing revealed the presence of Stachybotrys spores on Nika's desk – but rather than searching for the source of the mysterious spores, the district resolved the problem by simply throwing out the desk (see "How Much Mold?" April 19, 2002). At the time, Vince Torres, assistant director of UT's Texas Institute for the Indoor Environment (and now vice president of the AISD board of trustees), said he was puzzled by the district's testing. "If you find [mold spores] anywhere, you need to know where it's coming from," he said. Because Stachybotrys spores are heavier than other types, the first thing he would have done, he said, is look up, at the ceiling.

Skeptical of AISD's testing methods and fearing that the district would drag its feet indefinitely on the issue, Van Deusen – who'd put her oldest daughter through Maplewood, worked as a classroom volunteer at the school, built gardens on the campus, and served as president of the PTA – realized she had no choice but to find a different school. She enrolled Nika in a charter school, where her health returned to normal, but the school ended in seventh grade. After that, says Van Deusen, she couldn't find a nearby middle school that didn't trigger her own symptoms, so she homeschooled Nika for a year "with the promise that" in ninth grade, she would go to McCallum – where her older sister had gone – "and have four years of stable high school community."

The promise seemed to come true when Nika's freshman year went by without much incident, as did the following fall semester – Van Deusen did notice water leaks in the building, but she reported them to staff, and Nika seemed okay. Then came March. When the spring rains hit, so did Nika's health problems. "After the fifth trip to the ER," says Van Deusen, "I kept her home."

When It Rains, It Spores

McCallum was among the 81 schools in the 2002 bond to receive repairs associated with water intrusion, and the 2004 bond pumped yet more money into the effort, with a portion of McCallum's $7.5 million going toward water-leak repairs and other preventative measures. "I thought after McCallum was remediated that Nika would have a home there," says Van Deusen. "That if there was a problem, if the roof was leaking ... it would just be this isolated thing – it would be easy to address." Instead, she feels that once again, the district has dragged its feet.

Although construction management director Curt Shaw says his department began initial work to repair leaks at McCallum in April, it wasn't until May 11 that AISD officials performed a walk-through inspection of the school that Van Deusen had requested. The group, which included Torres, Shaw, Principal Michael Garrison, and assistant director of maintenance Brad Shaver, didn't find much mold, but they saw evidence of its best friend, water.

"We did have some problems with some leaks that were causing moisture to come into the building, which of course, that coupled with the right medium, you can get mold pretty quickly," says Paul Turner, executive director of facilities for AISD. As it turns out, water had been accumulating inside a small storage shed – known as the "penthouse" – on McCallum's roof, right above a part of the building where Nika's locker, and some of her classrooms, were located. "What appears to have happened is some of the work that was done up there in the roof area ... didn't turn out to be as high quality as it needed to be," Turner says. "Since the work has been done fairly recently, it wasn't something that made us very happy." Though the warranty period for the roof work around the penthouse has expired, Turner says the roofing company responsible for that work has been making the necessary repairs and replacements this summer at "no cost to the district."

"I was a bit surprised to be having those kinds of leaks at McCallum because of the bond money spent there," Torres said after the tour. "The most important thing is investigating further to see if water has made contact with organic material." Molds are not picky eaters, and all they need to grow is a little moisture and some kind of organic matter: Sheetrock and wood make a hearty feast, for example, while brick and plastic don't, although a bit of moist dust on top of brick or plastic – like that responsible for some moldy ductwork in one McCallum classroom – is fair game, says Torres. The seeming increase in recent years of mold-related illness is often attributed to the increased use in the Seventies and Eighties of building materials, like drywall, that are appetizing to mold. The predominant material found in McCallum, which was built in 1953, is "structural glazed tile," says Shaw, but there are some organic materials in the building, he says, including some plywood paneling and wood trim above the lockers. "That was the primary thing that we could see that was affected by the moisture," says Shaw. "There was some Sheetrock on some flat surfaces in that general area, but it didn't appear that any mold was telegraphing that way."

Once moisture meets its material, mold can bloom within a day or two – but it wasn't until May 28, two months since Nika had become ill and more than a month since she'd left school, that AISD followed up on the walk-through with air quality tests in five of Nika's classrooms. When the lab results came back on June 3, they showed mold spore levels to be lower inside the building than outside – "which is normally the case," says Turner – with absolutely no evidence of either Stachybotrys or Aspergillus. Van Deusen herself took a swab sample from the wall above Nika's locker that week and cultured some heinous-looking molds within a few days – but lab results received by the Chronicle last week revealed no Stachybotrys or Aspergillus, either.

Good Grade, Bad Test?

Still, Van Deusen remains unconvinced. It's possible, for instance, that at the time of the air quality testing, heavy spores like Stachybotrys simply weren't airborne. In addition, the lab that analyzed the samples only magnified them by 600, she says – that scale wouldn't necessarily detect smaller spores like Aspergillus. The lab report includes a fine-print disclaimer, in fact, that says, "Some species with very small spores are easily missed, and may be undercounted." Of most concern, however, is the argument that air sampling isn't the method of testing AISD should be using in the first place. According to Ritchie Shoemaker – the Maryland doctor who wrote the book Mold Warriors in 2005 – air sampling is "what usually is done when people are trying to hide something." Shoemaker works with patients who suffer from what he calls "WDB" illnesses – sickness linked to water-damaged buildings. He has also published peer-reviewed research on the topic and backed plaintiffs in mold litigation cases.

"Air sampling ... involves taking a sample for five minutes – maybe 10 minutes – of one area of a classroom without any control on ambient conditions," says Shoemaker. "Is the window open? Is the door open? Is the HVAC open? Is it Monday morning before the kids come in? Is it Friday afternoon in the middle of recess when the doors are open, the dust is being kicked up?" In 2002, a more charitable Torres nonetheless had similar criticism, noting that "a major problem" with AISD's testing was "a failure to mention the conditions under which the tests were conducted and the protocols followed when conducting the tests."

More importantly, says Shoemaker, counting spores in a given sample misses the point: "Spores are very large structures, about 3 to 8 microns in size, and they don't cause nearly the same problems – in fact, less than 1 percent of the problem – compared to fragments of these fungal compounds." Research from 2005, he says, "showed that the sources of toxins and inflammagens – 99.8 percent of the material that hurts us – was carried in fragments smaller than 1 micron." A fragment, he says, "will go right through that air sampler, and the air sample will never count it. Those samples get deep in the lung, too.

"The real issue looking at schools," says Shoemaker, "is that we now have wonderful sampling techniques available to look for fungal DNA to rapidly show the presence or absence of some of the really bad actors that we know make people sick." He's referring to the Environmental Protection Agency's Environmental Relative Moldiness Index, which the EPA says "provides a simple, objective evaluation of the mold burden in a home." The ERMI is both cheaper and more accurate than air sampling, says Shoemaker: "For $300 you can find out within a week whether there is a significant problem or not."

Shaw and Shaver were unfamiliar with the ERMI test when asked and at press time were waiting on a call back from the EPA to learn more about it. "I think we're approaching this stuff head-on," says Shaw. "It's not like we're trying to avoid it." Still, they stand by the air quality testing that AISD uses. Shaw says that the test cassette for each room costs around $30, that Stachybotrys is among the standard molds the lab looks for, and that the test has indeed picked up Stachybotrys spores in the past. Shaver also agrees that when conducting air sampling, "you want to try to capture the conditions" that are typical to a classroom's everyday activity, and says that in the past, if they've had to sample after hours, an industrial hygienist has used a leaf blower to "stir up the air to capture whatever might be an irritant." It's also important to emphasize, says Shaver, that air quality testing is only one among many tools the district uses when diagnosing a building – observation, for example, is key. If there's one thing they've learned, says Shaw, it's that they've "got to recruit building occupants" to be vigilant in reporting mold and leaks, and they've developed a brochure to educate teachers and staff about indoor air quality.

"The district years ago was not responsive," says Torres, but "over the years it has developed protocols to respond." As a result of the bond money, schools have better HVAC equipment allowing more air exchange, he says, and according to Turner, the district is working with the University of Tulsa "to study the indoor air quality in fifth-grade classrooms to determine if a relationship exists between better indoor air quality and improved student achievement." Unfortunately for the district, one thing that hasn't changed is the lack of state-mandated guidelines for mold testing, due to the fact that ongoing research has yet to reveal much consensus about the mechanisms by which molds and other WDB compounds might make people sick and how far-reaching the health effects really are.

Same Mold Story

Mold has been a topic of increasing concern over the past decade both in the health-care community and in the media, especially since 2001, when Dripping Springs resident Melinda Ballard famously won a $32 million judgment – later reduced to $4 million – against Farmers Health Insurance for mold intrusion in her home. Ballard's family suffered breathing difficulties, memory and hearing loss, and bleeding in the lungs, among other things, after Stachybotrys took over her house in the late Nineties. Van Deusen traces her own symptoms to a Stachybotrys outbreak in her home in 2000 – her doctor at the time told her that the mold could explain the migraines, vomiting, and seizures she'd been experiencing while living there. Her family stayed in a hotel for six months before she recouped the cost of the ruined building from her insurance company. Unable to sell or rent out the house, Van Deusen spent $12,000 of the insurance money to have the house torn down.

Because of the potential for litigation against builders, landlords, and insurers – as well as the disparate range of symptoms patients attribute to mold and the difficulty of proving causal connections – mold-related illness is a controversial topic. The American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine published a position statement in 2002 arguing that "current scientific evidence does not support the proposition that human health has been adversely affected by inhaled mycotoxins in the home, school, or office environment." The paper has been used widely by mold-litigation defendants to debunk plaintiffs' cases and has become controversial even among some ACOEM members. In 2007, a Wall Street Journal article revealed that "the paper was written by people who regularly are paid experts for the defense side in mold litigation," and after that, physician James Craner – a member and fellow of ACOEM himself – published his own peer-reviewed rebuttal citing evidence from documents subpoenaed from the organization that "ACOEM's development of its Mold Statement involved a series of biased and ethically questionable practices centered around undisclosed conflicts of interest."

In 2004, the Institute of Medicine wrote that "studies have demonstrated adverse effects – including immunotoxic, neurologic, respiratory, and dermal responses – after exposure to specific toxins, bacteria, molds, or their products." Research following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita further suggested links between mold and illness, says Shoemaker, and has prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to reverse its position on mycotoxins, beta-glucans, endotoxins, and inflammagens – the "bad actors" found in water-damaged buildings. The levels can get high enough to make you sick, they now say. "That paper is one that really changed the approach of the CDC, and then over the next couple years, it's been fascinating to see how one government body after another – including the EPA, including Health and Human Services, and including the GAO report of September 2008 – has pretty much shifted the entire thrust of looking at water-damaged buildings," Shoemaker says.

Despite these recent changes, the ACOEM paper continues to carry influence. It was suggested as a resource by one helpful doctor interviewed as part of the research for this article – while Craner's dissenting report was suggested by yet another. As doctors face their own struggle navigating the mixed messaging surrounding the ever-evolving body of research on the health impact of water-damaged buildings, thrust into the middle of the controversy are public schools. According to the EPA, half the nation's 115,000 schools have problems linked to indoor air quality. Just a quick Google News search reveals schools dealing with mold remediation efforts right now in Clarksville, Tenn.; Greensboro, N.C.; Mount Vernon and Martinsville, Ill.; and Richmond, Va. But while schools are struggling, so are patients, and the problem seems to be pitting the two against each other.

Doctor's Orders

Nika's last day of school was April 22. After that, says Van Deusen, "She was immediately getting better; her energy was bouncing back; it was clear her body was healing." Still, Van Deusen needed to provide AISD with a doctor's letter both to prove the legitimacy of her daughter's absence and to qualify for homebound educational services so she could finish her courses. But Nika had only recently gotten health insurance, and she had no established health provider. "I had to be very careful when I'd go into a doctor's office, because you don't want to look like crazy mold mom, but you want to give them a medical history and enough data," says Van Deusen. No doctor, it turned out, was willing to draw any conclusions about Nika's illness. Instead, says Van Deusen, some told her, "I don't know anything about mold toxicity," while others said, "Mold cannot make you sick." Meanwhile, the clock was ticking – with finals fast approaching, Nika's 10th-grade year was on the line. In desperation, Van Deusen turned to an unusual source for advice – retired Lt. Gen. Paul Carlton, a former surgeon general for the U.S. Air Force.

Van Deusen met Carlton in 2004 on a plane en route to Houston. The flight was grounded in New Orleans because of bad weather, and as the passengers sat in the plane waiting, the flight attendants opened the doors to let in fresh air – and, apparently, mold. Van Deusen went into anaphylactic shock. A flight attendant searched for a doctor among the passengers and found Carlton, who resuscitated Van Deusen and treated her with epinephrine and Benadryl. When she explained that she was hypersensitive to aflatoxin – a mycotoxin produced by Aspergillus – he replied, "Where did you serve?" As it so happened, says Van Deusen, Carlton also had a history with the mycotoxin, reaching back to the Gulf War, during which he performed autopsies on soldiers who'd been exposed to aflatoxin, an apparently useful agent in biowarfare. Like Van Deusen, Carlton, too, has a sensitivity to mold.

When Van Deusen couldn't find a doctor to diagnose Nika, she called Carlton, who now works at the Texas A&M Health Science Center. He agreed to examine Nika, and on May 1 he wrote a letter to AISD on her behalf: "Stop Miss Nika Perry from attending school now," he wrote. "She has an immediate life threatening condition that has apparently been triggered at school and could suffer an anaphylactic reaction at any time and die. She should not return until her complete evaluation and therapy are completed, probably several months in duration."

AISD accepted the letter, Nika was enrolled to receive homebound services, and her health was getting back to normal – but her other problems had only just begun.

It took almost 30 days from Nika's last day of school to begin work with homebound services, leaving her little time to prepare for finals. Still, she passed all her classes with the exception of those for which no homebound services were available – Latin and dance. Meanwhile, she's facing a summer of doctor visits and medical tests, and an uncertain future. So far, she doesn't know where she'll go to school her junior year, and she still has no diagnosis.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.