The Webberville Conundrum

Austin's plans for an eastern landfill hit a little obstacle – the people who live there

By Lee Nichols, Fri., June 6, 2008

Back in the early Eighties, Dave and Joann Gunlock bought themselves a little piece of paradise: 30 acres of rolling pasture and post oak forest out in eastern Travis County, hidden away from any major road and seemingly well removed from the growth that was changing Austin from a college/government town into a metropolis. It's a tranquil, serene place, at least when Dave is not hammering away on one of his many projects intended to perfect their "dream house." Cows lazily munch grass. Joann tends her vegetable garden. Overhead, a group of black-bellied whistling ducks, with striking red bills and stripes of white on their rust-colored wings, glides down to a pond at the bottom of a picturesque valley. Next to the pond grow wild grapes, from which Joann makes jelly. Roses adorn a flower bed, complemented by a variety of wildflowers in the field. Bluebirds, cardinals, and other songbirds create a constant musical backdrop. "I like to wake up, go to my window, and survey my kingdom," Dave Gunlock says. Out here, it feels like the city is a million miles away.

It's not.

Austin's problems, inevitably, are Travis County's problems. In fact, history shows that Austin's problems most likely will be eastern Travis County's problems. If it's ugly, unsightly, undesirable ... those sorts of things always seem to end up on this side of I-35.

And now it might happen yet again. Right across the street from the Gunlocks' paradise.

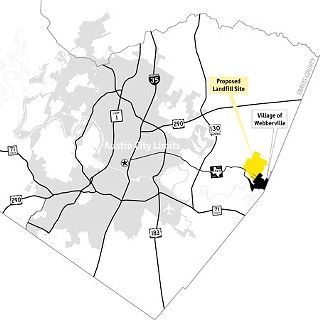

The city of Austin owns a 2,853-acre tract of land just outside of the Village of Webberville. It's a piece of property the city considers a "valuable commodity," in the words of one official report, and Austin isn't interested in selling it. The city wants to do something big with it, although it hasn't yet certainly decided what. The leading possibilities: a solid-waste facility, an Austin Energy substation, or a wastewater treatment plant. Maybe even all three.

This next part probably won't surprise you: The Gunlocks are pissed. And so are many of their neighbors and the elected officials who represent them.

East, West, and Forward

"We moved out here because it was country," says Dave Gunlock. "This is beautiful land. It's every bit as pretty as the Hill Country. ... It's free of the city pollution – and now they're trying to bring their pollution to us."

Dave and Joann actually moved onto the property in 1995. Dave retired from the Air Force in 1978 and still works a bit in the office-supply business; Joann is a retired legal assistant. He speaks with a country accent that originated in Illinois but could easily pass for rural Texan. He smiles when he shows off his property but clenches his jaw when he thinks of its possible future.

"Everything good goes west of I-35," he complains. "Everything they don't want comes east of I-35. And that's not right. We have the prisons; we have the dumps; we have the tank farms; we have low-income housing; we have halfway houses, gravel pits. ... You name it, we've got it."

Despite living in Austin for 22 years, I can't say I'd ever been to this particular part of Travis before. I'd pictured it as just flat, boring farmland, punctuated by a fair amount of poverty. And to be sure, there is much in the area that meets those expectations. But there is also beauty. FM 969 twists through patches of dense forest and around surprisingly high hills as it winds its way to the county line; a quick detour from the road takes you to a sprawling county park abutting the Colorado River, where one can put in a canoe and float down to Bastrop and beyond. Yes, there are some mobile homes, but, "There are some beautiful houses out here," Gunlock says. Like his, "They're just set back off the road so no one can see them."

Austin City Council member and Mayor Pro Tem Betty Dunkerley sees something else when she considers what is officially known as the Webberville tract. Long known as the nuts-and-bolts finance minister of the council – a reputation that preceded her tenure on the dais, going back to her days as an assistant city manager and financial services director – Dunkerley views the property as a means to provide for the needs of her constituents, as well as future generations of Austinites. Although the city continues working toward adoption of a "zero-waste" program like those of San Francisco and other cities, she says that doesn't eliminate the need for proper solid-waste planning.

"It's not going to be too long before our community and our county is going to be stranded," she worries, noting that city facilities in Creedmoor also accept trash from other cities. "Even though we move toward a zero-waste goal, there's still landfill requirements, and there's requirements for businesses and for industries that support the reuse of our recycled materials – and that place, part of it, would be perfect for that. It still leaves a very large buffer on the Webberville side.

"I'm a short-termer over here," adds the council member, who will be term-limited out of office in June (to be succeeded by either Cid Galindo or Laura Morrison). "This is going to be a major problem for those that come after me, whether they want to think about it or not."

Dueling Perspectives

Concern over a landfill on the Webberville tract is not new. It's been hanging over the heads of area residents for several years – Webberville Mayor Hector Gonzales first wrote to Travis Co. Commissioner Ron Davis pleading for help in 2005. (With about 300 residents, Webberville has a history dating back to the 1850s but was only incorporated as a village in 2003.) Although the Austin City Council doesn't represent them, Webbervillians have gone to City Hall imploring Austin's government to go elsewhere for its future landfill and utility needs.

Gonzales grew up in Austin and says he moved out to Webberville for an environment that is more "healthy and wholesome" with "some of the freedoms you have in the country that you don't have in the city."

"Unfortunately, it seems Austin is following me," he says.

Gonzales and Webberville went so far as to try to buy the tract in spring of 2007. Somehow, the village mysteriously came up with $21 million – more than three times the appraised value that Travis County places on the land – and offered it to Austin Energy, which holds the title to the property. As was reported in the Statesman just last month, the cash actually came from Carpenter & Associates, the would-be developers of the Villa Muse project just across 969 from the Webberville tract. No go, said the city. The true value of the land goes well beyond the appraisal value, says Austin Solid Waste Services Director Willie Rhodes, and must also factor in the future needs that it can meet.

The issue came to a boil in March of this year, when Dunkerley placed a resolution on the council agenda to move forward with exploring development of the Webberville tract. That brought a quick response: Davis placed a motion before the Commissioners Court on March 18, to amend the county code to specifically prohibit a landfill on the tract, and a prehearing press conference was led by state Rep. Dawnna Dukes that brought together residents, environmentalists, and civil rights leaders to denounce the city and support Davis' motion. The motion died for lack of a second – Precinct 2 Commissioner Sarah Eckhardt told disappointed Precinct 1 residents that the amendment would be "legally indefensible" unless the county could provide an alternate location – and became moot anyway when Dunkerley pulled her own council resolution to allow for more discussion. Still, the hearing allowed eastern county residents to display the depth of their anger and fears.

It also allowed the city to tell its side. The city engaged three consultants to advise it on the suitability of the property: Geomatrix, Shaw-Hicks, and Klotz Associates. In February, Geomatrix presented the city with an analysis, albeit one that all sides acknowledge is only preliminary. The report describes itself as merely "screening-level," a quick eyeballing of the property to check for "fatal flaws" – regulatory and technical factors that might immediately rule it out for solid-waste uses. The study found no apparent fatal flaws but noted numerous factors that would require further study and which might present challenges or constraints, including: floodplain and groundwater issues, a power-line easement, historical and cultural sites, wetlands on the property, and roads that are currently insufficient to handle the truck traffic that a landfill would produce.

Assistant City Manager Bert Lumbreras tried to stress to the commissioners and the anti-landfill contingent present that the proposed facility is not a done deal, emphasizing that deeper examination of the property might scuttle the plan. But make no mistake: He and Rhodes clearly share Dunkerley's desire to use the property. To that end, Lumbreras is striving to reassure area residents that the project would be a benefit to the community.

"Let me be clear," Lumbreras says. "What we have talked about is a state-of-the-art facility. We're talking about an eco-industrial, environment-friendly, green-principled type of facility. I know people here are referring to it as a landfill, but what we're talking about here is all of the different components that will strongly complement our zero-waste initiatives, our recycling, and our diversion to utilize landfill space at its most minimum level. A landfill is still going to be necessary, but it's not the typical landfill that we were accustomed to building 40 or 50 years ago."

Mark down the residents, and allied activists, as unreassured.

Aside from the fears of toxins, as well as property value and nuisance issues that justifiably worry those living near landfills, "To me, it's more about the truck traffic than anything else, and that's why I'm opposed to it being used for the zero-waste uses as well," says David Beck, another area resident. (Like the Gunlocks, Beck doesn't live in Webberville proper but belongs to the surrounding Park Springs Neighborhood Association.) "It doesn't make sense to have one central [facility] that's not even central – it's way out, on the edge of the county. You've got all these trucks traversing the whole county just to get out there, wasting all that gas. It's totally unnecessary traffic. So even the zero-waste facility seems silly to put out there."

Gonzales flat-out doesn't believe Lumbreras. He notes that the city already has 24 years left on a contract with Texas Disposal Systems and thinks the dump will be used to import more waste from other counties. "They're creating a cash cow," he alleges. As for promises of a buffer, "There can't be a large enough buffer," he says ruefully. "How do you buffer all those trucks? The smell? The debris? There's got to be a more suitable location. If they had taken our [buyout] offer, they could have bought someplace more suitable."

Geology or Racism?

Those who support the facility completely disagree with that last assessment. To them, this tract – which was originally acquired per voter approval to host a coal-fired power plant and is currently leased out for agricultural uses – is the perfect location, and maybe the only location. "I think there are very few other options that anyone has for things like a wastewater treatment plant or a landfill or an enlarged [power] substation," says Dunkerley. "And the tract is large enough that I really think it can be very well-buffered so that it will not be a nuisance to surrounding properties.

"And the other fact is that, with the development along SH 130, it's really critical that we have some substantial infrastructure in that region, and there's simply not very many sites available within Travis County to do that. ... The other options are so limited, and the geography is so limited. Folks can say, 'Why don't you put it on the west?' But that isn't an option simply because of the geography. It has nothing to do with anything other than that. So the areas that possibly could be suitable are generally in our desired development zone."

Rhodes backs her up, saying that state law regarding aquifers precludes much of the western side of the county. And legal issues aside, Lumbreras says: "Really, this bottoms out to geology more than anything. The geology is that the eastern parts of the county have the soils that are conducive to this type of service."

Hogwash, says Dukes. For her, Davis, and some other east-siders, this is just another attempt to dump what isn't wanted in an area that is predominantly poor and minority. "For many sessions, I and many other Democrats attempted to pass buffer-zone bills to prevent the overutilization of land within the minority community for the unwanted facilities," Dukes says. "The Republicans and the big oil companies would tell us, 'No, it's not environmental racism; it's because of the geography or the price of the land.' That's a Republican argument, a conservative argument, from those who don't want to think about the socioeconomic issues that have been forced upon people who primarily have not been able to afford to go and buy a piece of land someplace else. Just because they're poor shouldn't mean that their quality of life and their environment shouldn't be taken into regard. That's what environmental racism is."

"[This] community has been crying out for justice for a long time," echoes Davis. "The city appears that it will not give this community any justice, and it just appears that it will gentrify and genocide this community."

More or Less Than Zero

The city's "zero-waste" proposal, still in the planning stages, figures prominently in the debate over what to do with the Webberville tract, but supporters of the policy don't agree on its role.

Citing ongoing fights between private landfill operators Waste Management and BFI (now Allied Waste) and residents in nearby Northeast Austin, Eckhardt thinks a publicly owned facility is essential to any attempt by the region to control its own wastes. "The only sure way for a county in Texas to dictate the location and the manner of garbage disposal within its confines is to control the dirt under the landfill," she wrote to constituents in her spring quarterly newsletter. This would allow the city to build a zero-waste compatible facility and to tightly control what kinds of waste, and from what sources, would be allowed (i.e., no importation from other counties). "When you own the property, when you have all these waste diversion components to it, essentially the city is in a better situation," Lumbreras agrees. "We can control our destiny when we control the property."

Robin Schneider of Texas Campaign for the Environment – which has an extensive history on landfill issues, including convincing Dell to take back and recycle obsolete computers and thus reduce electronic waste in dumps – takes a totally different tack, saying zero waste is exactly why we don't need a new landfill.

"I think that the region should focus on zero-waste policy and programs before doing another landfill," Schneider says. She doubts the ability of the city to run a landfill well, saying that Austin's strongest environmental drives have come from citizens – with city staff lagging behind. Moreover, she says: "My understanding is that a lot of places that have zero-waste plans do not own their own landfills. It's not a precondition for zero waste. ... The city of San Francisco, I think, is furthest ahead – they don't own a landfill, and they've got over 70 percent diversion."

She also worries that a landfill would inevitably become a self-fulfilling project. "The downside of having the city spend the amount of time and money it takes to permit a landfill means that they're going to have to fill it up and not [divert trash]."

Dunkerley says Schneider's position underestimates the urgency of Austin's current needs. "The problem with that is that there's such a long lead time on permitting and constructing landfills that I don't think we have that luxury." And she flat-out rejects Schneider's latter point: "I don't think that's true. Cities are not into things for investment purposes. They're into things to protect the health and welfare of the community."

Buried History

Two of those "need more study" issues in the Geomatrix report stand out as potentially problematic, and the anti-landfill advocates are placing a heavy emphasis on them: archaeological/historic value and the environmental issue of springs on the property.

At the top of a big hill on the Webberville tract are the remains of what was once apparently a homestead. Currently, the ruins are well-hidden. Indeed, our guide on a recent tour of the property had a hard time finding it himself. After much hacking of brush with a machete and getting turned around more than once in the thick, unspoiled forest, we finally came upon a bit of brick wall protruding from the dirt and a huge cistern imbedded deep in the ground. Judging from a few beer cans at the bottom of the cistern, the site may have hosted a teenage drinking party or two.

The city's official position is that it isn't certain what the ruins are. Those opposing the landfill are dead certain that they are what's left of Fort Webber, the homestead of John Ferdinand Webber, an early settler and the village namesake who received a land grant in Austin's colony in 1832, and with his wife, a freed slave named Silvia Hector, may have been the first non-native settlers in what is now Travis County.

Regardless of whether it's actually Webber's home, the ruins are clearly something of archaeological and historical importance, as is at least one graveyard (and possibly more) on the property. Our guide showed us the Banks-Woods Cemetery, a small plot of land by an abandoned house containing dozens of graves mostly dating from the 19th century. Dave Gunlock says it isn't the only one – a neighbor claims there are at least five more cemeteries tucked away on the property. A 2006 Hicks & Co. report concluded that the tract "has a high potential for both prehistoric and historic sites."

The ruins are "one of the most significant historical properties in the county, next to the Capitol," says Dukes. She has no doubt it's Webber's home. "Oh yes. We do know. There's been research, and there will be a requirement for further examination and review if the city does attempt to move forward or request for permitting. There will be archaeological requirements. ... Webberville is certain that it's Webber's home."

Residents seem equally certain that a multitude of springs ought to be a roadblock. "It didn't really show up on Geomatrix's report," says Beck. "That creek runs pretty much year-round. ... There's a lot of water on that land." Gunlock agreed: "In the wet season, these hills just seep water constantly. The water level is right up to surface."

Indeed, the Geomatrix report is silent on the presence of springs; although, as stated, it was only intended to be a preliminary overview of the land. Its main mention of groundwater simply states, "If shallow groundwater is confirmed to be used as a drinking water supply in the Site vicinity, monitoring systems for any landfill would need to be particularly robust to ensure public protection and meet state regulatory expectations." Or, "Another option ... would be to provide an alternate water supply to groundwater users in the vicinity of the site." Residents report that wells are in use in the area. "I have two dug wells on this property, the deepest one being 25-foot," says Gunlock. "They're spring-fed, and they've never gone dry."

Nowhere to Run

It's without argument that the Webberville tract presents a spectacular opportunity. The problem is, the opportunities are multiple, depend acutely on one's perspective, and not all of them are good. It could be the opportunity to save our city from a looming waste crisis. Perhaps it could be a driving force in our efforts to reduce, reuse, and recycle. It could be a chance to commit to equity between the east side and west side. It could be a park. It's also yet another opportunity to show that the city just doesn't care what happens east of the freeway or another failure to cooperate with our neighboring communities. It might be yet another chance to revive the undeclared war some say is being waged between the environmental and minority communities. It's either visionary or more of the same. It's damned if you do and damned if you don't.

"When you look at this land, you don't think, 'Oh, that would make a great landfill,'" says Beck. "There's lots of old trees, a lot of old-growth forest on that area. You've got oak trees that are 100 years or better, cedar trees that are 100 years old or better. ... Old pecans out there, too. A variety of vegetation."

"We're not trying to make this into one issue," says Dukes, "but we're just trying to show a slight hypocrisy here – that the city would oppose something like Villa Muse, that that community was in favor of, but would support something that the community was in opposition to."

Dunkerley said she hears those complaints – although she'll likely be out of office before this issue gets resolved. For her, those who would reject such uses of the Webberville tract have failed to answer the crucial question: "Where would they suggest we put it? That's my answer to them." For those that say, "Go west," she repeats: "There is not a place in Travis County that is suitable for this type of infrastructure, except the area in our desired development zone, and [the Webberville tract is] part of our desired development zone. We would put it someplace else if we could find enough space, but we've not been able to find it. People keep saying there are thousands and thousands of acres, and they have yet to come forward with any. I think it's a figment of imagination."

Gunlock doesn't buy Lumbreras and Dunkerley's geographic arguments.

"They say they're gonna line it if they dig a hole out there. ... If they can do that, then they could also put the landfill out in west Travis County and line it. But they say they can't put one out there because the limestone has cracks and fissures in it. Well if they can line one over here, then they can line one over there."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.