Porn Busters!

The FBI and the AG are hunting for cybersex – and to hell with the Constitution

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Aug. 17, 2007

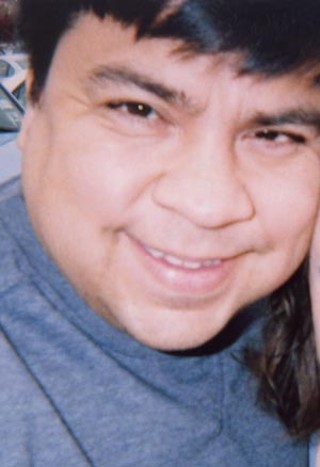

On June 9, 2004, Javier Perez's dream of becoming a college math professor came to an abrupt end. Just after 6am, Perez's housemate was jarred from sleep by pounding at the front door of the Oak Hill house they shared with one other roommate. A brace of law enforcement officers -- FBI agents, accompanied by investigators with the Texas attorney general's Cyber Crimes Unit -- was demanding entry. By the end of that morning, Perez's academic ambitions were finished, and by December of the following year, Javier Perez (known to his friends as "Jerry") was headed to a federal penitentiary in Louisiana to serve a 57-month sentence for possession of child pornography.

At first, however, Perez had no idea what was happening or that he'd inexorably wind up in federal prison after pleading guilty to the possession charge. He had no way of knowing that he wasn't even the initial target of the officers' investigation -- as indicated by their search warrant -- nor that by having a shared Time Warner Cable Internet service account in his name, he'd wind up in their investigative crosshairs. And he certainly did not know that the laws governing Internet usage, pornography, and even search warrants -- and more importantly, the Fourth Amendment right to be free from unlawful search and seizure -- could be so easily manipulated in order to achieve "cyberporn" prosecutions and convictions.

Perez was sound asleep when the officers arrived, bearing a warrant signed by federal Magistrate Judge Robert Pitman. The warrant asserted that in February Perez had transmitted, via the Internet, a series of allegedly pornographic videos, depicting minors engaged in "sexual activity," to a woman in upstate New York who he had supposedly met in a Yahoo! chat room. The woman contacted local police to report seeing the videos, which she said she believed were being played on a TV placed in front of a webcam, including a video of two young girls dancing around a room, clad only in ballerina tutus. (The woman told police she'd seen other videos, depicting explicit sexual activity involving prepubescent minors, but the ballerina video was the only one the police actually saw.) The Lakewood, N.Y., police contacted the FBI, leading agents with the Buffalo, N.Y., field office to issue an administrative subpoena to Yahoo! Inc., seeking the identity of the person the woman had been chatting with -- someone who'd logged in with the name "stephanmee2003" and was using the screen name "famcple." Yahoo! told the FBI that "famcple" was the name used by a "Mr. Rob Ram" and that, at the time the ballerina video was transmitted, "famcple" had been online using an Internet protocol address owned by Time Warner Cable. The New York agents subpoenaed Time Warner seeking subscriber-billing information associated with that specific IP address. According to Time Warner, that IP was assigned to Javier Perez's Road Runner account and billed to him at his Oak Hill home.

The information was passed to FBI Special Agent Robert Britt in the San Antonio field office. Britt ran a utilities check and confirmed that Perez's name was on the Austin Energy account for the house on Scenic Brook Drive. That was the extent of the official investigation; using just this basic information, Britt drafted a warrant, attesting that because "famcple" -- that is, presumably, Mr. Rob Ram -- used the IP address linked to Perez in order to transmit allegedly illegal pornography, the government could reasonably infer that evidence of said illegal activity would be found at Perez's home. In other words, he told Judge Pitman, the mere association between Perez and the IP address in question created probable cause for police to search his home and to seize any computer equipment found there. On June 7, Pitman signed the warrant; two days later the agents came calling.

Perez didn't hear Britt and the others arrive (eight officers in all, he recalls), although the commotion roused his housemate Lee Atterberry from his bedroom in the far corner of the house. Atterberry opened the door to find a contingent of armed officers standing on the front walk. He was surprised -- and it appeared the officers were as well, he later recalled. "I thought [they'd] made a mistake," he testified in federal court in September 2005. "This was Javier Perez's house." Javier Perez was an accomplished musician (he'd played trumpet in the UT Longhorn Band and taught piano to numerous kids), and he was a genius-level mathematician -- friends were amazed by his ability to perform complicated computations in his head, and parents were impressed by how he could demystify mathematical concepts for their children whom he tutored. He was an avid winemaker, using local wild grapes; he was a trusted lead teller at a local branch of Wells Fargo bank; and he was rarely at home, because he was always out working or having fun with friends. Why in the world would the feds come calling for Jerry?

Atterberry told Britt that he rented a room from Perez, and Britt asked if "anyone else lived there," Atterberry recalled. "I said yes. There's Robert Ramos, and we're both, yes, renting rooms from Jerry." Following a length of computer cable that curled along the hallway and disappeared into each of three bedrooms, Atterberry showed the officers which bedroom belonged to which man. The officers ignored Atterberry's and Ramos' rooms -- and, apparently, the trail of ethernet cable that hardwired each man's computer to the Time Warner Internet modem -- and went right to Perez's door. (Britt told the court that the officers made only a cursory check of Atterberry's and Ramos' rooms, to make sure they were "secure.")

Perez was asleep, sprawled amid the piles of clothes on his waterbed, when he heard a man's deep voice coming from outside his locked bedroom door, followed by a series of loud, shuddering knocks. Perez was groggy and confused. "I thought it was a friend of mine, joking around," he recently recalled during a phone interview from prison. Before he could react, the agents had "broken down the door. I didn't know why they were there, so I'm very confused," he recalled. "Within like 10 seconds, I was being pulled out of the room." The agents took Perez into the kitchen, where he was questioned for several hours. Meanwhile, the team of officers searched his room, removing computer equipment and plastic storage tubs filled with spindles of computer discs.

Britt asked him, did he do any "Web stuff?" Perez recalled. No, he answered; Britt asked about "Web chat-room stuff. [And] about screen names. I knew something was up, but I never did any of that. I was never interested in webcams or 'chatting,'" Perez recalls. "I'd e-mailed [only] like five people in the last 10 years. I'd rather just call." The questions kept coming and none made any sense: "The FBI kept talking about [chat] 'transcripts,'" Perez said. "I said, 'Show me the transcript, maybe I can help you figure it out.' [Britt] said, 'No, I'm not going to do that.'"

By noon the officers had departed, taking with them Perez's computer, two hard drives, and nearly 4,000 CDs seized from his bedroom and from storage tubs stacked in his garage. The officers failed to find a webcam or any videos of child pornography -- like those that prompted the woman in New York to call the police -- or any information linking Perez to the name "Rob Ram" or to the Yahoo! screen name or login name they'd uncovered and specified with their subpoena, including the names "stephanmee2003" and "famcple." But they did find images that officials say are of child pornography, some involving prepubescent minors, on some of the discs taken from Perez's house. (The agents later claimed that Perez directed them to the discs containing child pornography, but Perez says he was held in the kitchen during the entire search.) In fact, there were many such images, they said, perhaps 600 in all (although this evidence is unavailable) -- more than enough to charge Perez, now 40, with possession of child porn and to put him away in prison until mid-2010, to ensure that he'll have to register with the state as a sex offender for the rest of his life and that he'll never again work as an educator.

No Warrant? No Problem!

It wasn't until Lee Atterberry opened the door, agent Britt would later testify, that he had any notion that Perez had housemates. As far as Britt assumed, Perez lived alone. Of course, he admitted, he hadn't done any investigation to discover whether his assumption was sound. He didn't drive by the house -- to see how many vehicles were there, for example, or to check the names listed inside the dented white metal mailbox planted at the curb. He didn't make a trash run -- seizing garbage from the can after it'd been rolled to the curb for collection -- as a means to check for occupant-identifying information, nor did he run the address through the Texas Department of Public Safety driver's license database or contact the post office to see whether multiple people claimed the address as home.

However, Britt cautioned from the witness stand during a September 2005 hearing to determine whether the search of Perez's home was in fact lawful, those sorts of investigative techniques are rarely, if ever, employed by officers working a child-pornography warrant -- at least not on the approximately 20 warrants that Britt had executed during his 41/2 years as an FBI agent. That sort of investigation wasn't necessary, he said: The warrant in question was for the residence, not for an individual, so it simply didn't matter.

Britt told the court that he remembered Atterberry answering the door that June morning but not what Atterberry said. "I don't remember exactly what he identified himself as, just identified himself as living in the place," Britt testified. "I don't know if he said he was a roommate." And Britt also said he had no memory of Atterberry telling him that another man, Ramos, also lived at the house -- amazingly, Britt said that it wasn't until "later," after he "left the premises" that he "discovered Robert Ramos was the name of the other resident." On its face, that statement, which contradicted Atterberry's testimony, reflects either incompetence or dishonesty.

What Britt knew and when he knew it is important. If, for example, he'd discovered that three people lived at the house before arriving on Perez's doorstep that morning -- and that one man, Robert Ramos, had a name quite similar to the Yahoo! account user, "Mr. Rob Ram," who allegedly transmitted pornography earlier that year -- the search at Scenic Brook Drive might have proceeded quite differently. It is hard to imagine that after encountering armed agents at his front door, Atterberry would've failed to mention that a third person lived at the house (as he testified he had done). The discovery of multiple occupants at the house created a hiccup in the raiding party's plans, causing them to pause (albeit briefly) before proceeding with the search but under significant limitations. The initial warrant authorized the officers to search Perez's entire residence, but after encountering Atterberry, the officers revised their approach: Without returning to the magistrate to detail the change of circumstances (as is usually required by law), they modified the scope of the warrant on the spot, to encompass only Perez's room and the common areas of the house. Aside from glancing into the other two bedrooms -- for security reasons -- the officers completely ignored those areas of the home and whatever computer equipment or other evidence might have been discoverable there. At the time of the search, Ramos was not at home.

Britt testified that there was in fact no evidence that connected Perez to the initial complaint -- that "famcple" had transmitted video child porn over the Internet -- other than that he was identified by Time Warner Cable as the person billed for Internet services at the Oak Hill home. Interestingly, Britt said he understood the effect of using a computer router in the house -- as there was in Perez's house, hardwiring Atterberry's, Ramos', and Perez's computers to the single Time Warner Cable modem. That meant, Britt explained, that inside the house each of the computers coming from the router was assigned its own internal version of the main IP address -- so that, for example, incoming e-mail would be routed to the right user -- but that, ultimately, all information leaving the house through the Time Warner modem would resolve back to the unique IP address the company had assigned to the house and "not to the router and to the individual computer," Britt said. From the outside looking in through the Time Warner account information, it would seem as though all computer activity inside the house were coming from a single source. It would take actual investigation to find out if there were one, two, three, or more users inside the house -- but that's not what the FBI did, Britt said. Instead, once the agents discovered there were multiple occupants within the house and multiple computers hooked up to the Internet, the agents decided to focus solely on the least discrete piece of evidence they had: the name of the person billed for Time Warner's services. In fact, the officers didn't even seize the router, although it was located in Perez's room. "I believe we talked about what we were going to seize and that Mr. Perez was the subscriber to the account," AG Cyber Crimes Sgt. Jeffrey Eckert, part of Britt's warrant team, testified in 2005. "So we focused on [his] room."

Meet the Predator

If Britt's questionable search of Perez's property had failed to turn up any contraband, the investigation into Javier Perez likely would've died. However, among the thousands of discs the feds seized from his home they did find allegedly contraband images. The definition of illegal child pornography -- that is, images depicting subjects deemed to be younger than 18 -- is subjective and depends on what the viewer (in almost every case, solely law enforcement officers) deems "obscene," "graphic sexual intercourse," or "lascivious exhibition of genitals or pubic area." Access to this evidence is tightly controlled -- defense attorneys must make arrangements to view the material and are not allowed to make copies, and reporters have no access. The arrangement allows prosecutors to cherry-pick evidence, perhaps selecting the most lewd images to present as representative, and limits defense ability to counter judgments about the age of the children allegedly depicted. In fact, there were apparently lots of pornographic images burned to numerous CDs Perez had randomly amassed over the years. This made it easy for the feds to label Perez as a devout collector of child porn.

Yet Perez, his family, friends, the children that he tutored, and their parents find that characterization stunningly inaccurate. Perez is not a sex offender, they say; he is not a predator nor would he ever think of hurting a child in any way, including by dealing in child pornography. Perez does admit that he had child-porn images in his possession that he downloaded from the Internet -- and in retrospect, he told federal District Judge Sam Sparks in December 2005, he grasped the fact that by downloading the material he might be contributing in some way to the illicit market. But he -- along with his family, friends, and a psychologist, Dr. John Watterson -- insists that his massive downloading was actually symptomatic of his personal battle with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Perez hoarded everything; his house was packed full of stuff -- stacks of mail covered the living-room sofa and a reclining chair; stacks of picture frames leaned against the kitchen walls. He saved everything. Perez's friend Rhonda Cluley, who lived at the house on Scenic Brook Drive for several months in late 2005, recalls the time she found 10 full cans of antiperspirant while cleaning the kitchen. She suggested Perez get rid of them, but he refused. "He never knew when he'd need something," he told her. An inability to discard anything is a hallmark of OCD, says Watterson, who has been in practice in Austin for nearly 30 years -- treating both sex offenders and obsessive-compulsives, among others -- and who diagnosed Perez with OCD in 2005. "It was very clear right from the beginning that Javier did have [the] disorder and definitely was a hoarder of all kinds of things," Watterson said recently. So it was not unbelievable -- nor uncommon, really -- that Perez's compulsion would also characterize his use of the Internet. Specifically, Perez told the court, he was trying to make a "backup" of all online content -- that is, the manic and absurd ambition to duplicate the entire World Wide Web, initially from Usenet sites. Although it sounds irrational, indeed impossible, it is not an uncommon mode of thinking for someone suffering from OCD. Watterson said he found Perez's account entirely believable. He likens it to a person who obsessively washes his hands. "I think someone with the classic OCD condition of hand-washing intellectually knows that they don't need to wash their hands for the 24th time, but they're unable to stop," he says.

And so it was with Perez's compulsive downloading. He couldn't stand the idea of his computer standing idle all day long while he was out, explains Chris Perri, one of Perez's attorneys. So Perez designed a simple program to keep his computer working all day long, copying all the content at every Internet address it could locate. When the disc was full, the computer spit it out; when Perez returned home, he'd remove the full disc, place it into a storage tub, insert a new disc and head out again. And so it went for about three years. Notably, Perez never reviewed most of the material he downloaded -- in fact, he didn't even label the discs he recorded, making it nearly impossible to go back and find anything in particular. The point wasn't to review the information but simply to gather it, Perri said. By 2004, Perez had amassed thousands of discs burned with tens of thousands of files, most of which he never looked at.

Inevitably, as anyone who has spent any time online understands, Perez's discs included pornographic content -- unfortunately, they also included alleged images of "child pornography." Perez insists that he did not seek this material out but that it was contained on sites that featured legal, adult pornography. While he was aware the contraband material was there -- he had seen some of it, he said -- he didn't intend to have it and thus didn't really think about it being there. "I explained that as going into the shopping store, and you can take anything you want for free," Perez told Judge Sparks during his sentencing hearing. "You want to grab everything -- well, I would grab anything, whether I can use it or not."

The sheer number of files meant there were plenty of potentially pornographic images to use against Perez, but compared to the entire lot, the percentage was actually far smaller than prosecuting attorney Grant Sparks (no relation to Judge Sparks) led the court to believe, Perri says. Among the remaining files were thousands of images of trains Perez had intentionally downloaded (he was interested in painting pictures of locomotives), recipes, and countless audio books. Notably, prosecutor Sparks did not proffer any evidence to demonstrate otherwise, nor to counter Perez's assertion that he never reviewed the files at a later date (presumably confirmable from the computer's internal records). Ultimately, however, it didn't matter: Mere possession of pornographic images of minors is illegal, and that was enough to send Perez to prison -- even though, as it turns out, Perez was not the person Britt and his men were actually, legally investigating.

The Mysterious 'Rob Ram'

If it weren't for a call to police made by a woman in upstate New York, it is unlikely that Jerry Perez would now be behind bars. Of course, what she reported -- being shown pornographic videos involving children by a 23-year-old man, "famcple," that she was chatting with online -- wasn't what Britt and his team actually found when they showed up at Perez's house. The evidence might well have been close at hand -- but they chose not to look for it beyond Perez's possessions. Yet from the available information, there was a greater likelihood that what the investigators were after was in Perez's house, behind the closed door occupied by Perez's housemate -- Robert Ramos. "Rob Ram," the name associated with the "stephanmee2003" login name and "famcple" screen name, was actually a shortened version of Ramos' full name, Atterberry testified in court. Ramos had a Yahoo! account, Atterberry said, but Perez did not. Armed with just this bit of information, Perri and Perez suggest it would be logical to conclude that of the three men living at the house on Scenic Brook Drive, it was most likely that Ramos was the one who had an online chat with the woman in New York. (In fact, Perez says that on the dates in question, particularly Feb. 27, at 5:35pm, when "famcple" transmitted the ballerina video, he wasn't even at home. Perez says his work schedule proves he was responsible for handling closing duties at the bank that night and he didn't leave work until 6:45pm.)

Amazingly, however, the official government position -- from Britt, Sparks, and more recently from Department of Justice spokesman Daryl Fields in San Antonio -- is that there was no evidence to suggest Ramos was actually the man the feds were after. For example, Britt completely dismisses the notion that he should have gone back to the magistrate for a new warrant after discovering that Perez had a housemate named Robert Ramos. "I have no evidence or probable cause to believe that Robert Ramos would be the subject [of the investigation] on this occasion," Britt replied.

In response to a list of questions I e-mailed to his office in San Antonio, Fields, who handles media relations for U.S. Attorney Johnny Sutton, reiterated Britt's contradictory reply: "The U.S. Attorney's Office received no evidence indicating that anyone other than Javier Perez was in possession of child pornography or that anyone other than Javier Perez transmitted child pornography," Fields replied. "Mr. Perez was found to be in possession of ... CDs containing child pornography and admitted to downloading these images via the Internet."

And there was additional evidence that Ramos was involved -- more than just the report provided by the woman in New York. Shortly after Britt's team left the house on June 9, 2004, Perez said he had a brief but startling phone conversation with Ramos, who, at the time, was studying to be a public-school teacher. He told Ramos the officers had been at the house and that they'd been asking about chat-room activity. "And he said, 'Yeah, they're looking for me,'" Perez recalls. "I said, 'What were you thinking?' He said he'd been doing it for years and 'hasn't been caught.' I was shocked," he continued. "He came straight home and got rid of everything," smashing his hard drive. Perez was furious. He told his lawyers, Perri, and his boss, Joe Turner, what had happened. Perez said he pleaded with Ramos to do something to help him out.

Ultimately, Ramos reluctantly agreed, and went to Turner's office on May 10, 2005 -- four months before Perez would go to court -- to sign an affidavit. "I own my own computer, which is a personal computer," Ramos wrote. "I connect and have access to the Internet through this computer. There is a cable modem that feeds the Internet to the three computers in the house," he continued. "At one time I used 'stephanmee2003' as my Yahoo login name. The name 'Rob Ram' is short for Robert Ramos." It was a stunning admission -- even to Turner, who reminded Ramos that he was acting without the advice of legal counsel. Still, Ramos stopped short of uttering the magic words -- "I did it." Instead, interestingly, he claimed that he had no "knowledge of the name 'fameple' or who uses it on Yahoo! chat rooms." Whether this version of "famcple" was an unintentional error (he also misspelled "Atterberry") in his handwritten statement (that was then transcribed into the typed version) or whether it was the means by which Ramos sought to distance himself from the whole ugly affair remains unclear.

"I am not aware of Javier Perez collecting child pornography," Ramos wrote in closing. "He has never told me he had child pornography. I was not present during the search and I do not know what occurred. I have never been arrested for anything before in my life."

Although Ramos' current whereabouts are unknown, I contacted him via a cell-phone number provided by Perez. During a brief interview this week, Ramos denied making any illegal transmissions. He said he did provide the affidavit, confirming that "Rob Ram" is a shortened version of his name and that the login name "stephanmee2003" was also his, but said he "never" told Perez that he was the person the cops were actually looking for. Ramos said he no longer owns the computer he used while living in the house on Scenic Brook Drive.

Although Perez admitted having possession of child porn, he was nonetheless adamant that the government's means of finding this evidence was in fact illegal -- requiring them to bend the Fourth Amendment and to warp the notion of investigative duties and the standard for probable cause in such a way that the new "standard" actually threatens most people -- not just the notoriously despicable alleged purveyors of child porn. If the mere association between an IP address and alleged criminal activity is enough to allow officers to enter private property and conduct invasive searches, Perri argues, then anyone that pays for Internet services is vulnerable to law enforcement scrutiny. Under the government theory asserted in Perez's case, the service subscriber is ultimately responsible for whatever illegal activity might be trafficked through his or her Internet account, regardless of whether that subscriber in fact had any connection to, or even knew about, that illegal activity. It is a new and nearly inexplicable standard that twists logic -- and legal precedent. "It gives the [government] the legal right to continue doing these searches, without ever having to investigate," says Perri. "They'd never have to leave their offices; they can just sit there, file administrative subpoenas, and draft warrants."

And so it went for Javier Perez, where the feds have turned established logic on its ear, insisting that Perez was in fact their intended target and that his decision to challenge the legality of the search at his home is frivolous. "He feels that an injustice has been served because Mr. Ramos perhaps was trafficking child pornography," Special Assistant U.S. Attorney Sparks told the court. "Not to be insensitive, but who cares[?] [Perez] was in possession of child pornography and receiving it."

Guilt by Computer

According to prosecutor Sparks, Perez's claim that he suffers from OCD is also meaningless. What matters is that by downloading so many illegal images, Perez actually "created a market, almost single-handedly, for the proliferation of child pornography," he told Judge Sparks during Perez's 2005 sentencing hearing. Without any supporting evidence, prosecutor Sparks took his argument even further, asserting that Perez was actually collecting child porn for the purposes of "whetting [his] appetite" -- as a prelude to preying on real children.

Sparks' assertion that Perez's extensive downloading actually created a "market" for child porn (although there is no evidence that Perez paid for any images) is highly debatable; his assertion that Perez was nothing more than a predator-in-training is baseless and inflammatory. Yet it is not surprising, because it represents well the new standard level of rhetoric, completely lacking empirical supporting evidence, that has become a hallmark of the official police and prosecutorial hunt for "cyberpredators" and child pornographers.

Technological advances, and specifically the rise of the Internet, have undoubtedly broadened access to child pornography -- once an industry of hard copies purveyed largely through the mail -- and may have created new avenues for sexual deviants to stalk and find victims, although the actual statistics are not necessarily persuasive. DOJ spokesman Fields says that in fiscal year 2005 alone, federal prosecutors charged 1,447 "child exploitation cases involving child pornography, coercion, and enticement offenses" against 1,503 individuals. Locally, since August 2004, the feds have prosecuted about 130 defendants on child-porn charges; most defendants plead guilty rather than go to trial, and most receive between two- and five-year sentences. (This is straight time, since there is no parole in the federal system.) The Texas AG's office has apprehended 93 individuals -- "cyberpredators" -- who actually attempted to meet a 13-year-old "girl" (an online role assumed by Cyber Crimes investigators). So far, says spokesman Jerry Strickland, the AG has a 100% conviction rate -- which at least suggests prosecutions impervious to any available legal defense. According to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, only about one-third of cyberpredator and kiddie-porn offenses are actually reported, meaning the scope of the problem isn't actually represented by the number of actual prosecutions -- but such numbers are highly speculative.

Nonetheless, the darkness at the heart of the sex-crimes story hasn't changed: It remains true that the majority of those who sexually abuse children -- including by creating and distributing child pornography -- are either related to their victims or else have otherwise legitimate access to the children they abuse. "A lot of people think these are kids that are abducted off the streets," says John Shehan, deputy director of the exploited children division of the Florida-based NCMEC. "Most [child victims] do have a relationship to their abuser. In the vast majority of cases, the individuals that create these images and abuse [these kids] have legitimate access" -- they're parents, uncles, brothers, teachers, and other close relatives and acquaintances, he says. This uncomfortable fact receives far fewer headlines and law official emphasis than the relatively rare but much more sensational horror story of hideous stranger crimes -- like the 2005 abduction, rape, and murder of 9-year-old Jessica Lunsford in Florida that has prompted a string of states, including Texas, to increase criminal penalties associated with child sex-predator crimes. (In Texas, the newly enacted "Jessica's Law" allows for the imposition of the death penalty for repeat offenders.)

It is the stranger crimes that make headlines and TV magazines and feed moral panic; they reinforce the specter of a menacing "bogeyman" that everyone wants to flush out from under the bed or, more often in recent years, from behind the computer monitor. The mere mention of "kiddie porn" or reference to "cybercrimes" is enough to invoke this contemporary bogeyman. But there are inevitable unintended social consequences, say lawyers, civil libertarians, and others, including psychiatric researchers and mental-health experts. All "sex offenders," no matter the circumstances, are lumped together as equally despicable and unsympathetic -- the understandable disgust for a literal, serial sex abuser is now also attributed to teenage lovers separated by a "consensual" year or by the casual possessor of images the government deems "pornographic." Upon conviction, all three defendants earn registration as "sex offenders," an official, lifelong scarlet letter reflecting that none so labeled is to be trusted, forever, and that all are equally dangerous. "Certain prosecutors want to rely on that [assumption]," says attorney Turner, a former Travis Co. assistant district attorney. "They want to lump 'em all together." And this conflation muddies everything -- particularly the application of the law. It also hardly serves to protect children, because such muddling also trivializes serious and violent sexual crime, making it more likely that such offenders will readily lose themselves amid hundreds of others convicted of what are, in rational terms, much less serious offenses. To date, there are 50,000 individuals -- from flashers to rapists -- listed in the Texas Department of Public Safety's sex-offender registry. Among them is Javier Perez.

This approach does have one advantage, at least to police and prosecutors. By reflexively invoking the sensationalized "kiddie-porn" menace, the government lessens resistance it might otherwise face to its tactics and interpretations of the law and especially to its application of the Fourth Amendment's ban on unlawful search and seizure, says E.X. Martin, a Dallas defense attorney with expertise in search-and-seizure methods in cybercrime cases. Under the guise of "making us safe" from potential predators, Martin says, the courts have granted law enforcement more and more leeway in establishing probable cause when considering warrant applications, such as the one FBI agent Britt sought to search Perez's home. "It's the hot-button deal right now," he says. "If you downloaded kiddie porn, they're going to kill you."

In hindsight, Perez realized that downloading the images, even unknowingly, was wrong, which is why he pleaded guilty to the possession charge. But he did not give up his right to appeal his conviction, an appeal now headed for the U.S. Supreme Court, because he does not believe that the means by which the feds ensnared him was legal -- or an appropriate use of their Fourth Amendment powers. Perez and his attorneys, Turner and Perri (who is preparing the appeal pro bono), say that the case exposes a fundamental flaw in the government's zeal to prosecute alleged child pornographers and sex abusers. "This is out of control, and a lot of it is really unfair," says Turner. "Part of the problem is that the people writing these laws [and judging defendants] don't understand the technology -- they are older folks making the decisions, and they don't understand the technology."

In pursuing Perez, the government abandoned its initial pursuit of "Rob Ram," the person actually alleged to have transmitted kiddie porn over the Internet, in favor of a strategy that assumes an IP address is as good as a fingerprint, says Perri, and that's frightening. The government assumption should make anyone who uses the Internet nervous -- especially those who might use an unsecured connection, those who provide wireless Internet access for customers (for example, bookstores, coffeehouses, restaurants, or even the city of Austin's Parks and Recreation Department), and small-business owners whose employees use computers connected via a router to an Internet modem. If Perez's conviction stands, it means that finding who is responsible for a specific illegal activity isn't as important as getting a green light to ferret out whatever illegal activity might be taking place -- by someone, somewhere. In Perez's case, the feds were, supposedly, interested in finding "Rob Ram" and stopping his transmission of pornographic videos involving children. Instead, they found, arrested, and convicted Javier Perez -- and let Rob Ram disappear into the wind.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.