Reefer Madness: Closing the Crack-Cocaine Gap

U.S. Sentencing Commission votes to close disparate gap between federal sentencing guidelines related to crack and powder cocaine

By Jordan Smith, Fri., June 15, 2007

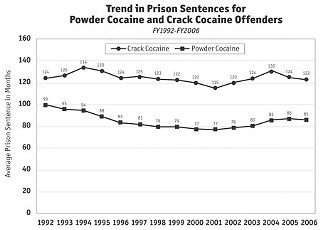

from 1997 to 2004, the difference went from 49% to 56%; in 2005 and 2006, crack sentences were about 44% higher.

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Report to the Congress, "Cocaine and Federal Sentencing Policy," May 2007.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission has voted to close the widely disparate gap between federal sentencing guidelines related to crack and powder cocaine, and unless Congress acts to block that decision, the new sentencing guideline will take effect Nov. 1.

The new guidelines reduce the possible sentence for possession of at least 5 grams of crack to between about four to five years, down from the current guideline of roughly five to six years in the federal pen. For crack-related offenses involving 50 grams of crack or more, punishment guidelines would drop to between eight and 10 years, down from 10-12.

It's about time, and it's the least they could do. Actually, it's the fourth time the Commission has considered closing the so-called "100-to-1 drug quantity ratio," which has caused draconian punishments for crack-cocaine offenders and the second time it has taken action to do so. It takes merely 5 grams of crack to earn a five-year stay in the federal pen under current guidelines, but it takes 500 grams of powder cocaine to earn the same punishment. The disparity means similarly situated offenders – defendants with similar criminal history and circumstances – receive vastly different punishments based only on a meaningless difference in the appearance of the two forms of cocaine. "Federal cocaine sentencing policy, insofar as it provides substantially heightened penalties for crack cocaine offenses, continues to come under almost universal criticism," reads the group's report to Congress, "and inaction in this area is of increasing concern to many, including the Commission."

The USSC is a quasi-independent arm of the federal judiciary, created in 1984 to create sentencing guidelines that would stabilize disparate sentencing practices among the federal courts. The guidelines provide a range of punishments for each federal crime while still allowing some judicial discretion. While the guidelines were in development, however, Congress acted to create a mandatory minimum sentencing scheme, which codified the now-reviled crack-powder disparity. The federal Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 became law at the height of the media-fed moral panic over the use of crack. (The crack-overdose death of University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias played a significant role in feeding this frenzy and fear of the drug, literally a chef's reduction of powder cocaine to its hardened state.) Sparked by the crack craze, the law imposed a series of man-min sentences designed, in theory, to dissuade drug use – that generally means a mandatory five years for possession of just 5 grams of crack, 10 years for possession of 50 grams. (And remember, there's no parole in the federal system, so 10 means 10.) In contrast, it takes possession of 500 grams of powder to earn a five-year sentence and possession of 5 kilos to land the 10-year man-min.

The 1986 law also impacted the sentencing guidelines, which generally adopted whole the man-min structure, around which the USSC then based its guidelines (generally by placing the minimum at the low end of the guideline range). Ultimately, however, mandatory minimums trump sentencing guidelines. Judges must first determine whether an offense qualifies for a man-min – if so, there's no meaningful way to avoid the man-min's imposition and no room for judicial discretion or mitigating evidence. And when a man-min isn't required, the guidelines, which mimicked the 100-to-one disparity, haven't provided crack defendants much relief.

Now the USSC says the crack-coke gap is simply wrong: The guidelines "sweep too broadly" and disproportionately affect "low level offenders"; and the law overstates the "seriousness of most crack cocaine offenses," failing to provide "adequate proportionality," such that the severity of crack-related penalties "mostly impact" minorities. The Commission is recommending that Congress review the man-min law to ensure that the most serious penalties are targeted for "serious and major traffickers" – in other words, suggesting that mitigation be incorporated into the sentencing structure. The USSC is also recommending that the man-min for simple crack possession be repealed and that Congress create parity by downgrading punishments associated with crack cocaine without increasing penalties associated with powder cocaine – because, the USSC report reads, there is simply "no evidence to justify such an increase." Of course, there are lawmakers who have sought to remedy the problem by doing just that, including Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., who has been vocal about his dislike of the current scheme – he told NPR last month that the current crack sentences are "too heavy … to be justified as a matter of public policy" – but seeks to reduce the disparity to 20-to-one by lowering the powder possession threshold rather than raising the crack ones. (Texas Sen. John Cornyn signed on in support of Sessions' approach last July.) Sessions' measure does propose modifying the man-min structure to reflect a defendant's "role" in the crime, which Mary Price, vice president and general counsel for the national advocacy group Families Against Mandatory Minimums considers a far more "holistic" approach to the problem. "To his credit," she says, Sessions understands how unfair it is that "low level people are getting the same sentences as king pins." Only House Resolution 460, by Rep. Charles Rangel, R-N.Y., currently proposes crack-powder parity. Among the bill's 10 co-sponsors are Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, and Rep. Dennis Kucinich, D-Ohio.

With its new report, the Commission used its authority to promulgate an amendment that would lower crack penalties, although it did not suggest a one-to-one scheme. The guidelines would reduce the ratio to between 80-1 and 20-1, depending on the severity of offense. It's a baby step, but a step in the right direction. Unless Congress acts to disapprove the amendment, the new sentencing guidelines will take effect Nov. 1. According to FAMM, the proposed changes would affect 78% of all federal crack cases, reducing sentences by an average of 16 months. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.