CSI: Travis County

Why is the Medical Examiner's Office so screwed up?

By Jordan Smith, Fri., June 30, 2006

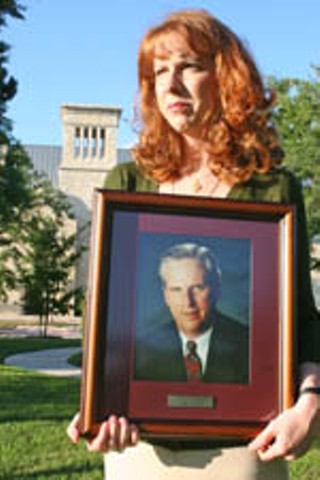

If life truly imitated art – or at least popular television shows, like JAG or Crossing Jordan or, most vividly, CSI: Anywhere – Lari Burson would've known what killed her father last summer, within about 24 hours of his death.

On Aug. 14, Burson's 59-year-old father, Guy "Mike" Burson, checked into the Round Rock Hospital, complaining of both abdominal and back pain. He'd previously had kidney stones, so his daughter's first thought was that he had another stone. But when she arrived at the hospital emergency room, she knew it wasn't stones – and she knew something was very, very wrong. "My dad is in the fetal position, lying on his left side, sweating profusely, moaning, and in tears [from the] pain," Burson recalled. "I crawled into [the hospital] bed with him, and I touched his back, and I remember him saying, 'Don't touch my back.'" Everything was tender – his back and stomach as well as his arms and hands, legs and feet, in which, Lari recalls, he complained he was losing feeling.

The doctors couldn't find a source for the pain: There were neither kidney stones nor gallbladder problems, as far as they could tell; tests revealed an aneurysm in his stomach, but it was small and hadn't ruptured, and it looked as if blood flow throughout his digestive system was normal. Eventually, he was moved from the ER to a regular bed, where he spent the night, waiting to see a specialist. Her father didn't look good at all, and his pain was intense, Burson says. She was frustrated and scared. In addition to Mike's mysterious and unceasing pain, his skin had begun to mottle – turning purple and blue, beginning in his abdominal region, and then spreading across his body in a pattern that looked like interlocking pieces of a jigsaw puzzle – and his temperature was dropping, from just under 98 degrees when he got to the hospital, to 95 degrees by the morning of Aug. 15. Both symptoms indicated a bad infection.

Moreover, overnight her father's abdomen had become increasingly rigid and distended, and by midmorning the doctors were getting ready to perform an exploratory abdominal surgery to look for the source of his pain and worsening infection. The wait was excruciating; Lari found her way to the hospital chapel and prayed. What was happening? Her father had been tired in the preceding weeks, mainly with work and worry over a move to a new house. But his symptoms appeared much more alarming than stress or exhaustion.

Several hours later, the surgeon emerged with his report: "The surgeon comes up and says, 'I don't have any good news for you,'" Burson recalls. About 70% of her father's bowel was dead. There was nothing they could do except close him up and provide comfort until he died; at most, her dad had 12 hours. "I remember everything was in slow motion," she says. "He told me [dad] was going to die. My whole world fell apart, and I was mad."

Lari went immediately to her father's bedside. "I was crying. He looked at me and said, 'How long?' Like he didn't know he was going to die," Lari recalls. "I said 12 hours at most. He looked shocked and started to cry." Family and friends were summoned; at his bedside they all held hands in prayer and then said their goodbyes. At the end, just close family – Lari, her paternal grandmother, and her stepmother – remained, and Lari held her father's hand. The end came quickly; Lari remembers her father's eyes, still so blue and clear, became fixed, and he coughed, "like he was drowning, and he literally was." Blood seeped from his mouth and nose and then he was still. "His favorite thing was to go fly-fishing," Lari says quietly. And so sitting there with her father's hand still in hers, she told him, "'You go fly-fishing now, dad.' And I think he heard me."

Open Question

It's been more than 10 months since Lari Burson said goodbye to her father, and she still doesn't know the cause of his death – or, more precisely, what caused the nearly complete gangrene of his intestines that prompted his sudden and painful demise. More alarmingly, she isn't sure which of the two drastically different causes of death assigned her father by Dr. Roberto Bayardo, chief pathologist and administrator of the Travis Co. Medical Examiner's Office, is the correct cause – or if, instead, the true cause has gone undetected, any evidence likely gone. "I don't want to go through the rest of my life without knowing what killed my father," she says resolutely. On the advice of her father's primary-care physician, the day after her father's death Lari called Bayardo to request an autopsy. She was desperate to know why he'd died, in part because her family has a history of digestive problems. In 1985, her paternal grandmother had a third of her stomach removed, and just a month before her father's death, Lari underwent an endoscopy. If her father's sudden death had a genetic component, Lari wanted to know.

Although he was busy, Bayardo agreed to take Lari's case as one of the 800 or so "private autopsies" that the TCME performs each year, for a $2,000 fee. Even at that price, Lari was determined to have the postmortem, and, talking with Bayardo on Aug. 16, her grief fresh and spilling into their conversation, Lari was reassured that Bayardo would solve the mystery of her dad's death. "I'm looking at this guy – tall, handsome, silver-haired, grandfatherly – thinking he must be full of wisdom and intelligence, that he must be smart as hell," she recalls. "And I'm thinking, OK, I'm going to pay him this money, and he's going to tell me how my dad died."

Yet, as the anniversary of his passing nears, Lari still doesn't know what killed her father – whether it was genetics, a bacterial fluke, or, perhaps, foul play. Since August, Bayardo has provided two completely different versions of Mike Burson's official cause of death. First, in a result that stunned Lari and her family, Bayardo ruled that Mike was poisoned, likely with rat poison, a conclusion he reiterated under oath at a November inquest hearing before Williamson Co. Justice of the Peace Dain Johnson. Toxicology tests revealed that Burson had levels of zinc and phosphorus four times above normal. "Well, the only compound that I know that can do that is what is called phosphine," Bayardo testified. "Phosphine is a rat poison. It kills the inside of the intestine and causes the bleeding in the [intestinal] wall."

But in January, Bayardo abruptly changed Burson's cause of death to bowel necrosis caused by Clostridium perfringens – a relatively common bacteria present in the intestines of up to 30% of the general population, but that has only rarely (three times in the last decade) been singled out as a cause of death. (C perfringens is most commonly known as pigbel, a bacterial infection that in the early 1960s – before the creation of a vaccine – was the leading cause of death among protein-deficient children in Papua New Guinea who had eaten poorly cooked pork. The extremely rare incidence of C perfringens infection in the U.S. is almost exclusively associated with poorly prepared institutional foods, according to medical literature.)

In short, instead of solving the mystery of Mike Burson's death, Bayardo confounded it with diagnoses that Lari's family has received with suspicion and grief. The initial finding that he'd been poisoned quickly led to distrust among family members, ripping them apart – all without leaving a hint of how the case might be resolved, Lari says. "What bothers me most is that I was never given a reason for the change" in the cause of death, or a way to explain the alarming tox results, if indeed C perfringens killed Mike Burson.

Most of all, Lari wonders if she did the right thing by going to the TCME for help.

Shadow of Doubt

It's been a rough year for the TCME – and Lari Burson isn't the only person questioning the quality of the agency's work. An outside audit last summer – prompted by the county's goal to secure accreditation by the National Association of Medical Examiners – described an office that is underfunded and understaffed (forcing the office's pathologists to perform in excess of 500 autopsies each year, far exceeding NAME's standard of a 350-autopsy maximum), is in desperate need of equipment and technology upgrades, and that operates without a stringent set of policies and procedures. In short, the report concluded that the combination of circumstances increases the "risk potential for mistakes" and the county's "risk exposure." The office has also made headlines with several high-profile errors – including news that in 2004 the office misidentified a deceased 85-year-old woman (or rather, her grave-robbed corpse) as the remains of a 23-year-old man who'd allegedly died only days before in a car fire (he was a prison fugitive trying to use the corpse to conceal his own disappearance). The accuracy of Bayardo's conclusions was also questioned in the police-shooting death of Daniel Rocha, when he initially told reporters that Rocha didn't have any scratching or bruising consistent with his having been in a fight with police and that his tox results showed he was clean, when in fact the autopsy report later revealed that Rocha was both scratched and bruised and that there was a trace amount of marijuana in his system. "When they come out and make public statements – public misstatements, in [such a high-profile case] it creates a really serious air of doubt about the ME's office," says Mike Sheffield, president of the Austin Police Association. "It impacts their credibility and the overall credibility of the investigation and makes people wonder, are these findings true and correct?"

To make matters worse, in March the three-pathologist office began hemorrhaging doctors – Deputy ME Suzanna Dana was the first to resign; in April, Bayardo announced his retirement, after nearly 30 years at the helm; and finally, citing substandard working conditions (among other concerns), on May 15 Deputy ME Elizabeth Peacock tendered her resignation, effective this Saturday, July 1. Although Bayardo told county officials that he would stay on until his replacement is hired (or until Dec. 31, whichever comes first), the doctors' exodus from the TCME means the county is left without a single full-time forensic pathologist to handle the office's growing workload – last year alone the office's three doctors conducted nearly 1,300 autopsies. Compounding the situation, county officials are now realizing that its "state-of-the-art" forensics center, which opened its doors less than a decade ago, is already outdated and entirely too small to accommodate the full complement of investigators and pathologists that the county will need in order to gain accreditation.

In short, the TCME – upon which not only Travis Co., but also 45 other Texas counties rely to investigate unnatural, unattended, or otherwise questionable deaths – is an office in trouble. The dirty little secret is that it has been in trouble for a long time; nonetheless, the office has only recently made it onto the Commissioners Court radar. Figuring out whom to blame for the current situation is far less important than figuring out how to save the sinking ship – one that must be righted before it threatens the stability not only of the county's criminal justice system, but also of the greater public health. "When someone dies and we don't have the science or the scientists to figure out why, nobody wins," says former County Judge Bill Aleshire. "It's bad, especially when we could've known."

Lari Burson found out that bitter truth the hard way: Death investigation in Travis Co. isn't anything like it is on television. "Families like mine [rely] on the determinations of the TCME office, not to mention police and lawyers," she wrote in a recent e-mail. "How many false [cause-of-death] determinations have ruined peoples lives?"

Ancient History

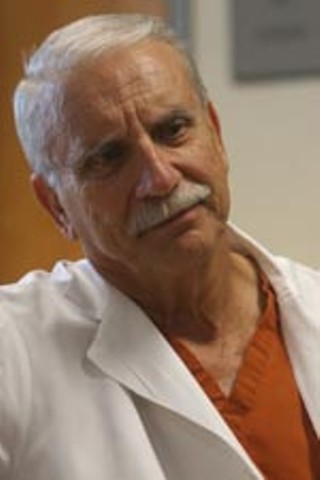

In the world of forensic pathologists there are "cutters" and "noncutters"; Dr. Roberto Bayardo, who has been Travis County's chief ME since 1978, is a cutter. The noncutters have assistants do the autopsy dirty work – making the Y-incision to reveal the sternum, manipulating the various organs, and manning the Stryker saw to open the skull. Some pathologists prefer this method; they stand back and observe, their focus unwavering. For a cutter, however, letting somebody else cut is unthinkable. "It's the most important part of the job," says Bayardo, standing in the ME Office's third-floor conference room, his burnt-orange scrubs rumpled, the pants too short over a pair of worn dress loafers. "I like to do my job. You get in there and pull out the organs and feel around." If you don't, he says, you "miss things."

Bayardo doesn't like missing things. Moreover, he rebuffs any suggestion that he has ever missed a single thing over his long career. He's been in the TCME office almost since it was created in July 1977, and it is his "baby." Bayardo was a deputy ME in Houston when he first came to the TCME in late 1977 to work weekends and holidays for the county's first ME, Dr. Robert Bucklin. After just a year on the job, Bucklin turned in his lab coat, and Bayardo was hired to take over as the fledgling office's chief – and only – pathologist. "When [Bucklin] took the job, the Commissioners Court said, 'We're going to give you more money [and] more office space,'" Bayardo recalled in a recent interview. "By the end of the year he saw that was a lie, and that they weren't going to do what they'd said."

Bayardo says the irony of Bucklin's story, now nearly 30 years old, isn't lost on him, but the office's current state of affairs suggests otherwise. Until 1992, when the county first hired Dr. Suzanna Dana as an assistant ME, Bayardo worked alone (he didn't even request an assistant until 1990, he told the Statesman that year) in the county's makeshift morgue attached to Brackenridge Hospital, where there was only room for four bodies in the cooler while the rest waited, lined up on gurneys in the hallway. "It was frustrating for a time, yes," he says – especially one summer when the air conditioning was out for several months while the county and the hospital bickered over who should pay for repairs. It wasn't until 1997 – eight years after voters approved a $2.6 million bond package to pay for construction – that the county finally completed the Travis Co. Forensic Center at 12th and Sabine, where the TCME Office is now housed. And in 1999, just two years after the building opened, it already needed nearly $1.2 million in repairs to fix a ventilation problem that had resulted in excessive moisture and mold growth inside the building.

Perhaps the story of the Forensic Center – if not the entire history of the TCME, starting with Bucklin's abrupt departure – should've been considered a harbinger. But, as with all things TCME, it often feels as if the past doesn't exist. By the time the building opened, Bayardo says, he was ready to retire but didn't, in part because the working conditions had so vastly improved. Sitting at the head of a long conference table, Bayardo leans slightly forward: "Working conditions are terrible," he says, snidely paraphrasing Deputy ME Elizabeth Peacock's letter to County Judge Sam Biscoe, resigning the position she's held since 1995. These conditions aren't bad, Bayardo says, looking around the room, its walls lined with bookshelves filled with medical journals and texts detailing various diseases and infections; "terrible" is working in the old morgue without air conditioning. "She should've been working there," he says.

Death by Numbers

Perhaps the Forensic Center is a state-of-the-art facility, at least compared to the TCME's former digs, where Bayardo toiled for 19 years. But to many – that is, to almost everyone but Bayardo – it's hardly a palace, and by NAME standards, it is unlikely that the facility would pass an accreditation inspection. The current building, with just over 14,000 square feet of useable space, is already too small for its 46-county workload. As designed, the building has just two "regular" autopsy stations and a single, separate suite for performing autopsies on decomposed bodies and on bodies suspected of carrying infectious diseases. In all, the building can only accommodate three pathologists (if one doctor works full-time in the decomp room) because the slab foundation "cannot be opened to modify plumbing drain lines," according to a report presented to county officials in February. The only way the current facility would pass inspection (in addition to several quick-fix upgrades to create more workspace and improve sanitation), the report notes, is if the county were to cancel its 45 interlocal agreements and serve only Travis Co. – and even then the building would only be adequate until 2025. In order to continue to serve even a portion of the other counties – those in the Central Texas region, for example, and those served by StarFlight – the TCME facility would have to be expanded to at least 33,000 square feet and be designed to accommodate at least seven full-time pathologists. According to the report, the building costs alone would run at least $6.6 million.

That figure doesn't include the cost of hiring pathologists, and the good ones don't come cheap. Indeed, for board-certified forensic pathologists, it's an employees' market. Nationwide, there are fewer than 1,000, a mere third of whom "function as full-time dedicated forensic pathologists working within and/or directing statutorily constituted medicolegal death investigation systems" such as the TCME, according to a 2004 NAME report. Part of the problem is that while there is a significant amount of additional schooling needed to become board-certified – at least nine years of formal education after college – the salaries offered by governments have not kept pace with private-employment counterparts. "You certainly don't go into [governmental medicolegal work] to get rich," says Dr. Phil Collins, head of pathology at Brackenridge and a member of the panel of local officials interviewing TCME pathologist candidates; "it takes a special kind of person to 1) enjoy the work and want to do it; and, 2) to go through all of the training required and then not be really rewarded monetarily on the other end of it."

Indeed, while a hospital pathologist generally clears $300,000 per year, the board-certified ME generally brings in a much lower salary – with 10 years of county service under her belt, for example, Peacock's base salary in 2005 was just $121,000; after 28 years of service, Bayardo's 2005 base salary was just $164,000. The salaries paid the county's pathologists might seem generous for most jobs, but considering the nature of the work in general, and specifically the TCME's demanding workload, the pay is hardly extravagant. While NAME standards require individual pathologists to perform no more than 350 autopsies per year – 250 is the ideal workload – TCME pathologists, on average, have performed over 500 autopsies a year since 2001. In fact, the office has long been understaffed. Since 1992, when the county finally hired Dana, the office has never had more than three full-time pathologists on staff at any given time. By comparison, Bexar Co., which is NAME-accredited, has six pathologists; Dallas Co., also accredited, employs 11; Tarrant Co., also accredited, has four pathologists and one fellow working full time performing autopsies. With the current workload, TCME would need at least five in order to meet NAME standards.

Cheaper by the Gross

In short, the county is in a real bind. And it is largely a manmade (and long-ignored) bind, created in large part by Bayardo with the tacit complicity of county officials, who have long neglected TCME operations, and who say they were taking for granted that Bayardo had kept them apprised of the office's needs. The root of the problems is budgetary – and, specifically, stems from the manner in which the office has been budgeted and the way pathologists have been compensated. When Bayardo first came on board as ME, the county had in place 11 interlocal agreements with surrounding counties to perform autopsies and death investigations. The arrangement, at first, was practical: Until 1992, Bayardo was the only ME in the entire Central Texas region. But that year, the number of county-approved interlocals began steadily to increase, and now, in addition to Travis Co., the TCME handles autopsy and death investigations for 45 counties – stretching across the state from Victoria, to as far away as Ward Co., in far West Texas. Again, while the arrangement is partly practical – and to Bayardo, even altruistic: "Those counties really need us, some have nowhere else" to go, he says – it is also a superficially crafty fiscal arrangement. According to last year's audit, of the state's 11 ME offices, the TCME relies most heavily on out-of-county, private cases (those done under interlocal agreement and those contracted by private citizens, like Lari Burson) to fund the office's annual budget and to boost pathologist salaries. Indeed, for FY 2005, the over-$1.7 million in revenue generated from private autopsy services was projected to cover nearly 81% of the TCME's total budget of just under $2.2 million – far outpacing all other counties. (Dallas Co. ranks second for its reliance on private cases to cover nearly 47% of its more than $4.3 million annual budget.)

Moreover, the county has used a portion of the out-of-county fees – $2,000 per autopsy since Oct. 1, 2004 – to boost the pathologists' otherwise below-market salaries. For each private autopsy, the pathologist makes $300; in 2005, Bayardo made about $127,000 in private autopsy fees, nearly doubling his yearly compensation for a total of roughly $291,000. Peacock pulled in an additional $67,000, for a total 2005 income of about $188,000. Since at least 2001, Bayardo has taken on the lion's share of private cases; from January 2001 through May 2005, he performed nearly 1,900 private cases, but just 89 of the more than 3,000 Travis Co. cases the office is statutorily required to perform. Not surprisingly, that means the bulk of the Travis Co. workload has been handled by the office's assistant MEs and, increasingly, by Peacock. In other words, critics charge, Bayardo has long had a financial disincentive to equalize the workload and to lobby for the county to hire additional pathologists. "The ... more-pay-for-more-autopsies incentive is what has led to the excessive number of autopsies per medical examiner," former County Judge Aleshire wrote in a February e-mail to county commissioners. "There was a built-in financial disincentive for [Bayardo] to ask for more assistant medical examiners in his budget to handle the increased workload. The result: lack of national accreditation for the office and over-worked examiners who make more mistakes."

Aleshire says that when he was county judge, the court had its own run-ins with the TCME. Commissioners learned that Bayardo was harvesting corneal tissue without family approval, he says, and later that he was contracting directly with outside counties for autopsy services and taking the fees without offering a cut to the county. In hindsight, Aleshire says the commissioners probably should've taken action then to restructure the office, but "we felt that we were over a barrel and couldn't replace [Bayardo]." They shouldn't have "let that influence our thinking," he says, but they did.

Aleshire and others argue that Bayardo's personal financial stake in the way the office operates has kept him from approaching the county, not only for additional employees, but also for all manner of additional resources. "If Bayardo came [to Commissioners Court] and asked for something, then he'd also get oversight, accountability, and the attention that he couldn't stand," Aleshire says. "Because Bayardo is too indignant about being supervised at all by the Commissioners Court, he hasn't gone to ask for things that [the office] needs."

Indeed, to hear Peacock tell it, working in the TCME office has often been frustrating and at times something of a nightmare. Not long ago, she says, she was working on a severely decomposed body while swarmed by insects – specifically, maggots and flies. For years, the office has relied on supermarket-variety fly strips to control the bugs, but this time it wasn't working. When she looked up from her work, she says, she realized why: The fly strips hanging over the autopsy station were already covered with insects. Peacock says she asked for new strips but was told that if she wanted them she'd have to buy them herself. "That's emblematic of the approach the office has taken all along," she says. Peacock says she's had to pay out-of-pocket for a variety of tools necessary to do her job, including recording equipment used to dictate findings during the autopsy process and other critical supplies, like a dissecting microscope.

Additionally, the office's relatively stagnant budget has meant the forensics staff is using increasingly old and outdated equipment. (Any increases have resulted almost exclusively from health insurance costs, slight wage increases, and additional toxicology positions – the latter necessary for state-mandated accreditation the lab earned last year.) Among other things, the office's X-ray machine is so old that the repair technician has had to scrounge off-market to find used parts to maintain it. The lack of funds also means that at times the pathologists do not have access to testing equipment that is often vital to the job. For example, says Peacock, if "a guy has a tumor, [most] doctors have" the necessary tools at their disposal to determine the tumor origin. "When I've asked for [access to those kinds of diagnostic tools], Bayardo's said, 'We don't need that; just guess.'" In essence, she says, "they're asking us to do malpractice."

That's not the sort of contemporary forensic practice one might imagine after watching the heavily staffed, glistening, equipment-laden labs on CSI: Miami.

Jumping Off the Treadmill

Dr. Peacock's May 15 resignation took many people, apparently including Judge Biscoe, by surprise. Judge Biscoe's public response was rather indifferent: If Peacock "doesn't think she can take us where we want to go," he said, then she's doing the "right thing" by resigning. The county's official response seemed to disparage Peacock as a money-grubber who was quitting only because the county's newly reconfigured salary scale – which boosts the doctors' salaries and does away with the $300 per outside autopsy fee (which brought Bayardo's salary up to $280,000 effective May 1, and would've boosted Peacock's pay to $188,000). In fact, however, her decision to leave shouldn't have surprised anyone in county government. Certainly, the monetary compensation the county was offering wasn't all that great – in part because, with just Peacock and Bayardo now on staff, the offer didn't take into account that the workload this year had increased. In other words, county officials were asking Peacock to do more work for less money.

But to Peacock, the monetary concern was only a symptom of the county's overall TCME problem. For years she'd expressed her concern about office operations – from the facility problems to staffing issues – and it seemed to fall on deaf ears. Every time she's spoken up, she says, she's been told things will be "fixed in a year or two," and that when that happens, "the place will look so different." In short, Peacock's concerns have been dismissed. This is distressing to Peacock, who says she loves her work and, more importantly, knows that the ME plays a critical role, not only in the criminal justice system, but also in ensuring public health. "It's not glamorous, but it is an important job." In addition to providing evidence in cases of traumatic or violent deaths – often supplying one of the most critical pieces of evidence in criminal prosecutions – the ME plays a crucial role in the child-fatality review team in looking out for elder abuse, in identifying potential outbreaks of infectious diseases, and as a point person for mass fatality and emergency-management planning. "The ME should have a finger in a lot of things – the office is the primary watchdog" of public health, she says. And, for years, Peacock has been the TCME's only point person on all of these things – "all the stuff the chief ME should be doing," she says, but a role that she says several years ago Bayardo tapped her to perform. "He's not on any of the committees because it cuts into his opportunity to make extra cash." Bayardo says that he did ask Peacock to take over the committee work because it was necessary to "divide the job of administration" in the office. He can't be in "two places at the same time," he says, and someone has to be in the office to perform autopsies. Although most experts, including the leadership of NAME, say that serving on the emergency medicine, fatality review, and other committees are a vital part of an ME's role in ensuring the public health, Bayardo disagrees. Serving on the committees has "nothing to do with the duties" of the ME's office, he says.

If nobody listens and nothing has changed, what does a pathologist do? "You quit," Peacock says. "It was a mistake to stay there that long; now I see it." It's like riding a bicycle that's "headed for a cliff and [realizing] you're actually able to jump off," she says. "Unless there's a major paradigm shift, that's where [the office] is heading."

Make No Mistake

Elizabeth Peacock is a practical, detail-minded person. While she can't necessary recall any specific mistakes she's made as a deputy ME (although there have been questions raised about her analysis of the death of Michael Clark in police custody), she realizes that working in a stressful, understaffed, and resource-poor environment increases the odds that mistakes – willful or otherwise – will be made. "Insufficient and outdated facilities, shortfalls in equipment and supportive manpower, insufficient funding ... can result in miscarriages of justice or unacceptable risks to the public's health," reads the 2004 NAME report. "Homicides may be missed, the innocent may be wrongly accused and/or incarcerated, the guilty may be wrongly exonerated ... or infectious disease epidemics can spread." Bayardo, on the other hand, scoffs at any suggestion that he's made any mistakes as the chief ME. "I've been here this long, and I think I've done a good job," he says. "Otherwise, the Commissioners Court would've gotten rid of me a long time ago."

Bayardo denies that working conditions would have anything to do with mistakes made by others. Indeed, he's quick to point out, for example, that the 2004 misidentification of the remains of an 85-year-old woman as those of a 23-year-old man was a mistake made by a pathologist who resigned last year, not his mistake. But as chief ME, he says, he takes the heat because each case is, ultimately, "my responsibility." The misidentification dust-up was among the cases Burnet Co. Justice of the Peace Peggy Shell Simon cited in a harsh letter she sent Bayardo in March, complaining that her county has been paying $2,000 a pop for work that "over and over ... has been unacceptable." (Simon did not return phone calls requesting comment for this story.) Bayardo says he was shocked by the letter and doesn't understand where Simon's anger is coming from. In sum, he says the controversies surrounding his office are generally "politically related" and usually hinge on one simple fact: "People like to have the cases resolved their way" – and when they're not, people get mad and point fingers at the ME's office. "But they don't have [access to] all the information we [use] to come to a conclusion."

What Killed Mike Burson?

That explanation infuriates Lari Burson, who by no means was looking for Bayardo to conclude that her father had been a victim of rat poisoning. Nor was she then looking for a sudden reversal, instead, that her father's death was caused by a generally nonlethal bacterium. And she certainly wasn't looking to be without an answer to the question of why her father died – which is exactly where she feels Bayardo has left her. In the last 10 months, Lari has spent a considerable amount of time surfing the Web, doing research on rat poison, C perfringens, and the TCME. She's been "overwhelmed" by information she's read on controversies surrounding the office – controversies that she says, sadly, have only confirmed her misgivings over the way her father's case was handled.

Unsurprisingly, Bayardo insists he didn't make a mistake in the Burson case. The reason he changed the cause of death, he says, is that even though he found extremely elevated levels of zinc and phosphorous in Mike Burson's system – the two components of phosphine rat poison – he was never actually able to find the poison itself. In November he testified that because Burson may have ingested the poison three days before his death, there would've been plenty of time for it to break down and leave only zinc and phosphorus. But in a recent interview, he insisted that his decision to change the cause of death was based on the fact that, although several days may have passed since Burson ingested the poison, intact poison still should have been detectable. At that point, he says, he determined that the C perfringens bacteria, which he found during the initial autopsy, must have been the real killer. In other words, instead of concluding that the bacteria was able to take hold because of the poison's deadly assault on Burson's system, he concluded that it was the bacteria alone that destroyed Burson's intestines – no matter how anomalous a killer it may be. "In my nearly 50 years of experience I'd never seen that," he says. "That's why I like my job. You never know what you're going to find."

Lari Burson believes Bayardo's conclusion is simply illogical – in part because the bacteria-as-killer theory does absolutely nothing to explain the extraordinarily high levels of two heavy metals in her father's system. "I wake up every morning wondering what caused my father such [an] excruciating death, and feelings of hopelessness prevent me from believing that I will ever have a credible answer," Lari wrote recently. Mike Burson was a "wonderful" father who cared about the community – he served as president of the Northwest Austin Chamber of Commerce, ran for a spot on the AISD board, and served on the board of the Umlauf Sculpture Garden, among other activities. "He had a general interest in the well-being of the community, and he served it well," she says. "However, my father has not been served well. There is a certain amount of trust and faith that is ascribed to the TCME that it doesn't deserve."

In the absence of any other explanation or answer, Burson suspects the truth is that her father's case has fallen victim to the turbulence and heavy workload at the TCME. "I want people to understand that these conditions could affect their families, as it has mine," Lari says. "When you are considering a cause of death that could fall in the category of homicide ... there is enormous consequence to that determination." Indeed, she says, perhaps Bayardo simply chose the expedience of a bacterial cause of death, one that would allow him to record the death as "natural," file the death certificate, and move on to the next case – and that scares her. "It's not just me who suffers. It's my entire family," she wrote recently. "We have no closure, just more questions and no firm answers. Just think about the official agencies and departments that rely on the answers that the TCME gives them. That's scary." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.