KUT by the Numbers

That ringing sound you hear? It's the cash register at Austin's public radio station

By Kevin Brass, Fri., Jan. 20, 2006

Last August KUT-FM sounded like a station in trouble. Just a few weeks before the end of its fiscal year, the public broadcasting station broke into programming to plead for an extra $100,000 in donations, citing an unanticipated revenue shortfall. Without the $100,000, listeners were assured, the station faced dire consequences.

But was KUT really teetering on the precipice? Only a few months earlier, the station had announced yet another record pledge drive. And the on-air pleas didn't mention the more than $3.3 million the station had in the bank or the new high-salary positions filled in recent weeks.

Today, station General Manager Stewart Vanderwilt acknowledges that the sense of urgency may have been a bit misleading. "We could have been more effective in talking about the importance of additional investment to achieve the station's goals," he says now, "rather than the 'coming up short' message."

In fact, KUT's public statements often don't present a full picture of the station's financial situation. With the insistent reminders that the station's beloved programming could vaporize without the support of "listeners like you," KUT often seems one bad pledge drive away from oblivion. Toss in scandals at the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the right wing's relentless drive to smite what it views as the liberal decadence of public broadcasting, and KUT comes across like a station under siege.

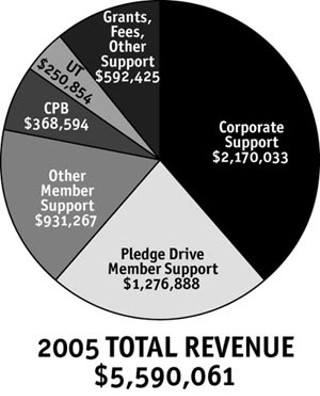

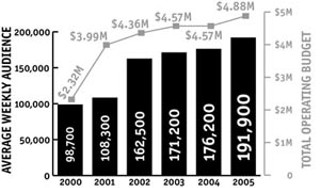

In reality, KUT needs more money because it is spending more money – more than twice as much as five years ago. According to a review of the station's finances by the Chronicle, it is also bringing in money at record levels, especially through corporate support. The station increased its cash reserve by $1.5 million in the last five years, the data supplied by the station shows, but it still must stretch to meet an annual budget that has grown to a projected $5.5 million for 2006, up from $2.3 million in 2000.

Far from a station in trouble, a detailed examination of KUT's finances reveals an operation aggressively raising money to fuel its ambitious plans, creating the type of cash flow that would make most commercial stations envious.

The Money Train

Although the conservative drumbeat against public broadcasting is a legitimate threat to the institution, in recent years it has made little impact on KUT's bottom line. The contribution to the station from the much-maligned Corporation for Public Broadcasting has actually increased from $166,000 in 2000 to $370,000 in 2005. But support from the University of Texas, the station's parent, has steadily declined, from $430,000 in 2000 to $251,000 in 2005. These days CPB and UT combined – the bulk of the station's so-called taxpayer-based support – accounts for only 11% of the station's blossoming budget.

To make up for the waning sources of public funds, KUT has morphed into a fundraising machine. In 2002 Vanderwilt hired Sylvia Carson, a veteran public broadcasting fundraiser, to fill the newly created position of director of development. In turn, Carson, who has worked as a fundraising consultant for public broadcasting stations around the country, hired a sales manager and three sales reps, creating a sales department to rival that of many commercial stations. In 2005 alone they raised $4.4 million, using the type of state-of-the-art techniques rarely seen at funky ol' KUT, from targeted mailings to a new aggressiveness in courting big donors (what Las Vegas calls "whales"). "We knew that the money was there," Carson said.

Although the station often tells listeners "80%" of its support comes from the "community," that is a tad disingenuous, especially if listeners are left with the impression the station survives thanks to soccer moms dipping into the cookie-jar fund. KUT's definition of "community" includes corporate money, which is increasingly carrying the weight of the station's budget. In 2005, money from corporate sources – which some public broadcasting critics fear is corrupting the basic premise of public broadcasting – accounted for 39% of the station's revenue, compared to only 23% from pledge drives.

Public broadcasting's increasing reliance on corporate funding, detractors say, undermines the basic concept of "noncommercial" stations established to serve communities, in theory free of the need to hump for advertisers. When public stations focus on wooing corporate money, "they are really off the mission of public broadcasting," said Jerold Starr, executive director of the Pittsburgh-based Citizens for Independent Public Broadcasting. One result, he says, is an increased emphasis on ratings and program development based on the ability of a show to attract sponsors. "When the whole idea of what kind of program to do is, 'Who will fund it?' you're being influenced," Starr said. "The people who get passed over are the poor and racial minorities, simply because they are not seen as a desirable demographic."

Vanderwilt insists corporate funding is not a negative issue for KUT, joining those public broadcasting executives who argue it is essential to the format's survival. "I haven't seen any evidence that corporate sponsorship has damaged public broadcasting," Vanderwilt said. "To the contrary, I think corporate sponsors have provided resources for more and better programming."

For KUT, corporate support usually comes in the form of "underwriter announcements," the noncommercials which sound very much like commercials. The Federal Communications Commission publishes guidelines for the underwriting announcements, which restrict certain kinds of rhetoric. For example, companies can't use "calls to action" urging listeners to "come on down." But as stations have grown more aggressive in courting companies, they've stretched the boundaries. As a result, the noncommercials on KUT might feature a restaurant touting its hot menu items, and a local market will assure listeners that "wine is our thing" – all within the FCC guidelines. "The vast majority of messages initially suggested we edit and rewrite," said Vanderwilt, who said the station rarely hears complaints from listeners about the wording of announcements. "Our greatest concern is how much is on," he said. "It's the clutter."

In an attempt to reduce the clutter, this month the station started cutting back on the number of underwriting announcements – usually about nine an hour – by about 20 spots a week. To make up for the loss of revenue, the station will likely raise its rates, Carson says, similar to the "less is more" plan of radio giant Clear Channel Communications. Depending on the number of spots purchased, KUT now charges about $140 for a 15-second announcement during morning drive time and about $120 a spot in the afternoon, although local independent retailers and nonprofits are offered a special rate.

Listeners Like You

While the announcements may bother a few listeners, they're a small annoyance compared to the ubiquitous twice-a-year pledge drives, which interrupt the same commercial-free programming the station is begging listeners to support. By the station's own estimates, listenership drops significantly during pledge drives; indeed, often the most compelling enticement for pledges is a promise to shorten the pledge drives if listeners cough up the quota.

Like many public broadcasting executives, Vanderwilt views pledge drives as a necessary evil. "Here's what's great about pledge drives," Vanderwilt said. "It's such a grassroots demonstration, a way to raise money directly from people who use the service. It's a direct referendum on the service. It makes the audience real for us."

In the fall, with the help of more than 400 phone-answering volunteers, KUT hit another record, raising $730,000 in nine days, a sharp contrast to the two-week-long drives of the past. The station was still almost $200,000 short of its $650,000 goal three days before the end of the drive, according to an e-mail Vanderwilt sent members, but an anonymous family foundation stepped up with a $30,000 matching pledge, helping the station once again to sail past its goal.

The amount raised by KUT pledge drives has steadily increased in recent years, from $746,000 in 2000 to $1.28 million in 2005. But the number of pledges has actually decreased slightly recently; the station is raising more money from fewer people. The average gift per person during pledge drives is now about $110 a donor, up about $10 per person.

"It's the vast middle that supports us," Vanderwilt said. That steady flow of $100 checks makes it impossible for public broadcasting stations like KUT to cut the tether of pledge drives, even though they know more and more listeners are wondering why, say, a commercial station like KLBJ-FM doesn't stage a pledge drive to help finance its programming. If KUT is running commercials and interrupting programming for pledge drives, what's the difference? Vanderwilt says he hears the complaints. "What we can and must do better is find a way to produce and conduct that conversation," Vanderwilt said.

There are signs around the country that listeners are getting fed up with the pleading nature of pledge drives. In December, listeners of the Detroit public broadcasting station WDET-FM actually sued the station for fraud, alleging that the station misled the public when it raised money during pledge drives and then dropped local programming in favor of national shows. "This is a public radio station, and their decision just completely disregarded the public and the community that is loyal to the station and financially supports it," Kevin Ernst, a lawyer representing a group of listeners, told a reporter. "People contributed for those local programs, not national programs."

Where The Money Goes

At the root of KUT's plea for funds is one basic, irresistible pitch – "We raise money for one purpose – to invest in programming," Vanderwilt said. Thanks to shows like Morning Edition and Eklektikos, KUT is one of the most popular stations in Austin, often beating the commercial stations in key time periods. KUT's average weekly audience has grown from 98,700 in 2000 to 191,900 in 2005, making it one of the highest-rated public radio stations in the country.

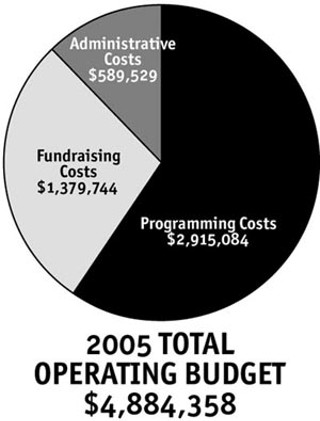

But, according to the station's reports, only 60% of KUT's revenue actually goes to programming. Although a public broadcasting radio station is a different beast from most nonprofits, the Better Business Bureau recommends that "at least 65% of a charity's total expenses should go to program activities." "We've used our resources to more than double the listenership of the station and we're connecting to more people than ever before," Vanderwilt said. "You can manage yourself to a percentage or manage yourself to service. I think we deliver a really good service."

KUT's programming investment has steadily hovered around 60% of revenue over the last five years – even though its programming budget soared from $1.4 million in 2000 to $2.9 million in 2005 – because management costs have also soared. Vanderwilt, who earns $132,000 a year, has over the last five years created a new level of managers dubbed "assistant directors." Program director Hawk Mendenhall, director of development Sylvia Carson, and technology director Richard Dean – all hired between 2000 and 2005 – sit atop the flowchart between Vanderwilt and three different divisions. Dean, who helped launch NPR.org, was hired in June to oversee a new "channels" department, charged with developing "a multiplatform strategy" for the station. He earns $86,000 a year; Carson, $87,000; and Mendenhall, $95,000.

Shortly after Dean joined KUT last summer – at about the same time the station announced the $100,000 shortfall – the station hired Marketplace producer David Brown, which added another big salary to the payroll. Brown – who is married to news director Emily Donahue – was brought to Austin for $78,000 a year, easily making him the station's highest-paid on-air personality, setting off grumbling among some current on-air staffers, many of whom have been with the station for decades. Brown produces and hosts the Texas Music Matters segment and is developing documentary and feature projects, but, at this point, he is usually heard on the air for only a few minutes a week. (Vanderwilt notes that Brown's salary is not out of line for a national producer.)

Click for a larger chart

At the same time, the amount the station spends to woo corporations and big donors is skyrocketing. The cost of fundraising – labeled as "resource development and listener services" on the station's Web site – rose from $538,000 in 2000 to $1.4 million in 2005. In essence, the station is spending more money to make more money, Vanderwilt says. "It becomes a question: Do you want a small service that can only be supported by the few that listen and the fewer that give?" he asks. "That's not our view at KUT."

Takes More to Make More

In one of the cruel ironies of public broadcasting, the more revenue and audience a station produces, the more it is charged by programming suppliers like National Public Radio. As KUT has grown, so have the fees for the station's most popular national shows, such as All Things Considered and Marketplace, which account for more than 50% of programming costs. For example, the price KUT pays for Morning Edition has risen from $136,000 in 2000 to $273,000 in 2005.

Meanwhile, KUT is also spending more money on local programming than ever before, thanks, in large part, to the creation three years ago of a news department, the station's first real attempt to move into public affairs. Although local news reports are heard only sporadically through the course of a day, the station spends $600,000 a year to maintain the news presence. Vanderwilt makes no secret of his desire to expand news programming.

A direct accounting for the costs of KUT's other local programs – primarily the music shows – is a bit murkier, due to the fuzzy math employed by public broadcasting stations. KUT breaks down the cost of individual programs, but it includes so-called "soft costs," stationwide expenses that are charged to each show. For example, the station tells members it costs $181,800 a year to produce Eklektikos, John Aielli's morning music show, even though the show's only real expense is Aielli's salary. But the figure includes a percentage of other programming expenses, such as the music director's salary and general production costs. By contrast, the station determines that the Friday-night-only music program Left of the Dial costs $21,500 a year, even though it is hosted by Music Director Jeff McCord.

The most expensive KUT-produced show, by far, is Latino USA, a half-hour nationally syndicated program carried by about 150 stations around the country. The show was originally produced by the University of Texas, but KUT absorbed it in 2001 and began cutting staffers and expenses, paring the budget from about $750,000 to $400,000.

Although more than half of the show's expenses are covered by grants and fees paid by stations, Latino USA's draw on the programming budget clearly irks Vanderwilt. "Going forward we have to think very hard about that investment and find a way to make sure it is really a benefit to our audience and our community," he said, adding that he has been encouraged by podcast interest in the show. "Over the next year we will really concentrate on how to improve the programming return on investment for Latino USA," he said.

The Bottom Line

"Return on investment" is the type of lingo rarely heard in the old days of KUT. And not everyone is thrilled with the new vibe. "Even some of my best friends say that it has turned into a corporate responder, instead of a neighborhood place that is cool," said station supporter Neil Blumofe, hazzan of Congregation Agudas Achim in north Austin and a member of the station's Leadership Council.

Given its recent success, some members of the Leadership Council were surprised when the station announced the $100,000 shortfall in August. In public statements, station management blamed the sudden need for cash on rising programming costs and the expense to keep the San Angelo signal on the air after equipment problems. And listeners came through with the money, providing further evidence of the unique bond between a public broadcasting station and the community.

However, while programming costs grew and a T1 line to maintain the San Angelo signal was expensive, there was no catastrophe waiting to happen if the listeners didn't send in their money for a free coffee cup, Vanderwilt acknowledges. The station's fundraising had simply fallen short of its annual goal, and they wanted to avoid an additional pledge drive, he says. A plea for funds often calls for an explanation and a sense of urgency, "And I have to say, sometimes we want to shorten the path between those, and skip to the urgency," he said.

Over the years the station has been slowing, and using surplus funds to grow its nest egg, which is expected to exceed $3.4 million in 2006. But about $2 million is encumbered at the start of each fiscal year to guarantee salaries and other expenses. "Once you encumber salaries, it's less than half a year's operating expenses," Vanderwilt said.

Nevertheless, Vanderwilt describes the station's finances as "healthy." While CPB suggests 2% net revenue per year is one sign of a station on solid financial footing, KUT is averaging about 5% a year in net revenue (what commercial operations might call "profit"), he says. It is now one of the largest public broadcasting radio stations in the South. Its $5.5-million budget compares to about $2.5 million for community-based Texas Public Radio in San Antonio, which operates NPR affiliate KSTX-FM and classical station KPAC-FM. "We're making our budget, growing our net assets, and investing in programs and equipment," Vanderwilt said. "I think the station is operating in a sound and healthy way." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.