Not So Red

A 'blue state' reporter journeys through the multicolored regions of the Lone Star State

By Rose Aguilar, Fri., July 1, 2005

Ed. note: Aguilar is a San Francisco-based journalist in the midst of a six-month road trip to politically "red states" – Texas, Oklahoma, Mississippi, Alabama, Montana, and Utah. She hopes to capture the look and feel of states that overwhelmingly voted for President George W. Bush and are largely ignored or dismissed by national progressive organizations and the national Democratic Party. You can track more of Aguilar's journey at www.storiesinamerica.org.

The drive from San Francisco to Texas took almost three full days, leaving plenty of time to count "Support Our Troops" ribbons and Wal-Marts, the two most common icons to be found on American highways. I left the liberal bubble of San Francisco on March 20, for a six-month trip to the so-called "red states," in order to talk to people about politics and why they vote the way they do. During election season, I cringed every time I heard "experts" from New York and Washington, D.C., talk about the differences between the "blue state voter" and the "red state voter."

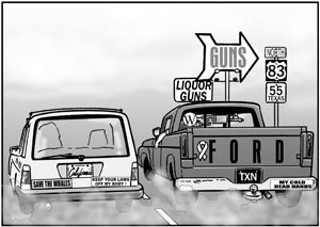

Back in April, 2004, The Washington Post reporter David Von Drehle wrote articles about "Americans from the reddest of red zones, the home district of House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-Texas), and the bluest of blues, the San Francisco neighborhood of House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-California)." Inevitably, Von Drehle described a Sugar Land Republican who owns several guns, drives a pickup truck, drinks Bud Light, and prays daily. Even at the time, I thought the series would have been much more compelling if he had focused on Democrats in Sugar Land and Republicans in San Francisco. In some ways, my current project is to do just that.

It's not simply a question of more interesting reporting. The larger problem is that the media's obsession with "red state" stereotypes has caused the country at large – including many progressives living in Democratic cities – to lose sight of the fact that states like Texas, Mississippi, and Oklahoma are in fact quite diverse in political culture, and inhabited by many more progressive activists than the stereotype suggests.

For immediate example, I didn't expect to stay in Texas for six weeks, and I could not have predicted that I'd meet such a wide array of people, including a Democratic cowboy from Linden who calls Bush a "wannabe cowboy"; a Pentecostal "redneck" from Seadrift who used to stage solo hunger strikes against corporate pollution and has written a book about environmental activism; Democrats who are breaking unspoken family rules by speaking out and protesting for the first time; moderate Republicans who believe Bush is the worst environmental president in history; Republicans who oppose Bush's foreign policy, but are afraid to speak out; as well as the more predictable subjects – a Republican who has a poster of Bush in her kitchen and Republicans who think Bush is not conservative enough.

Highland Park Haze

If nothing else, the exercise has broadened my own political perspectives. Traveling in Texas, I've met more Republicans over the past month and a half than I have in the past year in San Francisco. It took a while getting used to seeing scads of "Bush/Cheney '04" and "Thinking Women Vote Republican" bumper stickers. Those are nowhere to be found in San Francisco. It's true that 54,355 people voted for George W. Bush in San Francisco, but most of those folks don't advertise their politics on their cars. (John Kerry received 296,772 votes – 83%, behind only D.C.'s 91%.) I'm sure conservative Texans, at least outside the major cities, would have the same reaction to anti-war and anti-Bush bumper stickers in San Francisco. That's a shorthand for how this trip has made me realize how easy it is to get trapped in one's own social bubble and to run exclusively among crowds with similar views. It may feel good to preach to the choir, but in the overall scheme of things, what does it accomplish?

Nevertheless, I brought my own preconceived notions about Texas with me, and wasn't quite sure how I would be received after introducing myself as a journalist from San Francisco. Aside from occasional comments like, "Is everyone gay in San Francisco?" or "I thought all California girls were blondes," I've been showered with Southern hospitality. In addition to doing interviews in people's homes, I've spent a lot of my time in the hot sun, interviewing people in the parking lots of grocery stores and Wal-Marts, and in indoor and outdoor shopping centers.

Having expected the worst, I was surprised to find so many anti-war, pro-choice Republicans who aren't happy with Bush's policies – but who also admit they are afraid to speak out. The day after Gov. Rick Perry flamboyantly signed anti-abortion and anti-gay legislation at the Calvary Christian Academy in Fort Worth, I asked people in the affluent Highland Park area of Dallas how they felt about the event, and whether they were concerned about breaching the separation between church and state. The majority of the people I approached said they hadn't even heard about Perry's grandstanding photo-op. The few who had agreed to answer a few questions – but also asked me not to use their names, for fear it would hurt their reputations and job prospects.

"You have to be very careful about what you say here. Depending on what circle you're in, it could come back to haunt you. Even though we're supposed to live in a free country and a free society, the government can still make life unpleasant for certain people," said a Republican woman in her sixties who voted for Bush (even though she thought Kerry did a "terrific" job during the debates). "I had a hard time. I even agonized over my ballot. I was uncertain. I was on the fence right up to the time I voted and when I walked out. I was not particularly proud of how I voted, and that's not a good feeling."

The rise of the religious right is also troublesome to many Republicans I've interviewed. "I'm a Christian, but I don't think George W. should flaunt his religion so much. The Christian right put him in office, and that took me by surprise. I didn't see that coming because I just wasn't attuned to how much power they had."

A fortysomething woman who was job hunting described herself as an "independent," and said she has lived in other countries and different states but has never experienced anything quite like the climate in Texas. "There's a conformity here that's beyond belief. I was amazed that Bush was even elected, and elected twice. I thought, don't you get it? The party-line thinking comes out of the religious culture, and I would hate to see the whole country go that way because we would become a fascist state. It would really scare me," she said. "You do learn to conform. It's very common. You learn the hard way. I consider it a rabid form of Republicanism. It's not like the East Coast Republicanism of the first Bush administration. That was completely different. Those Republicans don't recognize these Republicans, but these Republicans are the ones who are dominating."

Certainly not all the Dallas suburbanites I met were so concerned about the political future under Bush. Several pro-war Republicans in Highland Park told me they believe Bush should stay the course in Iraq and continue fighting for "freedom and democracy." Significantly, none said they have any personal connections to Iraq.

And there were more than a few Democrats in these upscale neighborhoods, but they tended to be unaware of their own numbers. All of the Kerry supporters I met in Highland Park – and there were quite a few – told me, "I'm one of the only Kerry supporters in this area." Perhaps if they weren't so afraid to paste their politics on their cars in the manner of their Bushean neighbors, they would begin to realize they are not alone.

Full of Godliness

The next day, to get a different perspective, I headed to the Southwest Center Mall in South Dallas. The change from Highland Park was striking. Hummers and other snazzy SUVs are the standard in Highland Park, two or three to a driveway in the endless two-story brick-and-glass neighborhoods. Once you cross the line to the South side, you see roads in disrepair, older tract homes and worn-out bungalows, and many more beat-up cars.

Unlike in the acreage of Highland Park Village, I didn't see any "W – Still the President" bumper stickers in the Southwest Center Mall parking lot. The mall itself has no coffee shops or bookstores, and sells mostly discounted clothing; there were also plenty of empty storefronts. Ninety percent of the shoppers were African-American; many were young parents. Despite my best efforts, I couldn't find a single Republican or Democrat in support of the U.S. war in Iraq. Yet, also in sharp contrast to Highland Park, every person I interviewed knows at least one person serving in Iraq. "My daughter-in-law's brother was one of the first who was killed there," said Cooter Rivers. "He was 19 years old, just out of high school and had no training. They had him missing for a long time. They didn't even ship his whole body home. The war isn't necessary. We should leave that country and bring our boys and girls home."

The South Dallas folks were no strangers to religious belief, and they even tended to be conservative on such hot-button issues as abortion and gay marriage. Most said they oppose both – but the Democrats I met, especially African-American Democrats, said those issues shouldn't be exploited for political purposes. "As a Christian, I don't agree [with homosexuality], but gays should be able to do what they want," said South Dallas resident Davion Matis. "I wouldn't encourage anyone to have an abortion, but women should have the option under certain circumstances."

I grew up in Northern California, and while I know many religious people, at home I've never been asked, "Are you a Christian?" or "Where do you go to church?" Those are the first two questions I'm asked by many people in Texas. In California, even in small towns, it's also uncommon to see a church on every corner. In Kerrville (population 20,245), Kerr County, where Bush received 78% of the vote, I saw 14 churches within a three-mile radius: First Baptist, Zion Lutheran, St. Paul's United Methodist, Impact Christian Fellowship, Kingdom Hall of Jehovah's Witnesses. ... In the Kerrville phone book, I counted 72 churches in all.

Different Kinds of Ministry

In that context, I've been attending church each Sunday to learn about different religions and to interview pastors and believers about the relationship between religion and politics. Since megachurches apparently played such a prominent role in the presidential election, I visited the Shoreline Christian Center in suburban Austin, a 47-acre facility with the capacity to seat 5,000 worshippers.

Shoreline's parking lot is filled to capacity, and many cars feature Shoreline bumper stickers. The auditorium is also packed; on stage is a 13-piece band and 32-person chorus. The featured sound is bad ensemble rock; the difference is that almost everyone in the audience, on cue, raises their hands high in the air, and most wave a Bible or have one at the ready. On my right, people jump up and down, screaming: "Jesus wants us to get to the summit!" After about 20 minutes, Shoreline Pastor Rob Koke takes the stage and begins preaching about the importance of valuing "peace." "I want you to be a peacemaker," he says. "The world needs peacemakers."

Koke preaches about conflict at the global and local level, but never specifically mentions the Iraq war. Afterward, I ask him to share his views on the war. "If you believe that the motivation was a lie and that there were no weapons of mass destruction and that it was all manipulated because of oil, then I think the net end result of that would be you would feel that it was wrong," he says. "But if you really sincerely believe that this is a defense of our nation and our values of nation, that we'll be safer as a nation after this process is over and we extend to the nations of the world a commitment to peace through strength and security, that's where that element comes in from our perspective. We think it's justified."

The following weekend, I visit St. Andrew's Presbyterian, also in Austin, but apparently located in a very different spiritual neighborhood – I learned about the church by reading a Web posting by Austin's Third Coast Activist Resource Center. The contrast with Shoreline is immediate. The church program prominently features the term "progressive," and during the service, the Rev. Jim Rigby, who is under attack from other Presbyterians for his progressive stands on gay rights and abortion, speaks about the importance of humor and laughter to get through the bad times – including times of war. "After the bombing in Iraq began, I went home and watched The Daily Show, and somehow it saved my life," Rigby says.

He tells the congregation that the notion that the U.S. media is "liberal" is "so funny," citing in detail a 2002 Fairness & Accuracy in Reporting study of the three major networks' nightly news broadcasts. By FAIR's accounting, of partisan sources on CNN, 75% were Republicans and only 24% Democrats; CBS had the most Republicans (76%) while ABC had the fewest (a paltry 73%).

I found it difficult to believe I was hearing references to The Daily Show and FAIR in church, and it led me to assume Rigby's congregation was full of Democrats. I was wrong.

Bob Bartlett has been attending St. Andrew's Presbyterian for 10 years. "It's such a friendly church," he says. "We don't care what nationality, race, or creed you are. We don't care how you dress or undress. We have open hearts, open minds, and want everybody to feel welcome." Bartlett says he "regretfully" voted for Bush, and is still on the fence about the war. He doesn't agree with the plan to privatize social security, and believes the economy is worse than it was under Clinton. "I think Bush turned out to be greedy, but I think we're better off than if we had Kerry."

In politics, perspective, even institutional culture, there's no comparison between Shoreline and St. Andrew's. The problem for our national politics is, the Shorelines of the South have so much more influence and visibility, and receive so much more media attention than do churches like St. Andrew's. I've since visited several Texas churches that encourage tolerance and acceptance, and I believe that if the national media more often invited people like the Rev. Jim Rigby to sit alongside the Pat Robertsons and Jerry Falwells of the world, the national dialogue about religion would slowly begin to shift.

Redneck Woman

Spending time in Texas has made me realize how easy we have it, from a political perspective, in San Francisco. Last year, our mayoral run-off was between a Democrat and a Green! Texas Republicans cringed when I told them that – many said they'd vote for the Green over the "enemy."

Anti-war protests in San Francisco are essentially a love fest; we might get a handful of pro-war Bush supporters, but they don't stick around for very long. If the anti-choicers dare to come to town, they're outnumbered three to one. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors recently announced an ordinance that would prevent the city from doing business with companies connected to sweatshops, and they're planning to put a tax increase measure on the November ballot. San Franciscans often get credit for leading the way – but rarely do we have to deal directly with an opposition. We need to get out more, especially into those areas of California that aren't nearly as "blue" as the major cities.

By the same token, if the national and alternative media occasionally spent more time in states like Texas talking to people of all political stripes – especially to moderate Republicans who aren't afraid of speaking out, or progressives who are speaking out for the first time – they would find the political climate in Texas isn't as black and white – or "red" and "blue" – as they continue to insist it is. "I'm a redneck. I was raised Pentecostal and listen to country music. So what?" says Diane Wilson, 51, a member of the feminist activist group Code Pink, a longtime environmental activist, and author of the forthcoming book, An Unreasonable Woman, about her battle to save Seadrift from industrial chemicals. She is accustomed to making good things happen under the official public radar. "Redneck progressives," she says, "are capable of a lot more than the media would have you think."

Aside from the commercial media, there's the Democratic Party. If the Dems ever want to rebuild their party on the national stage, the leadership can no longer afford to ignore dedicated and determined activists who live in the state with the second-largest number of electoral votes in the country. In recent elections, the national party has pretty much consigned Texas to suburban fundraising junkets, and to the loss column on election day. The most recent result was the congressional re-redistricting blitzkrieg of Sugar Land's Tom DeLay, which relegated both the state and the national Democrats to minority status for the rest of the decade. There's plenty of blame to go around, but the official Democratic organizations can accept their share of it.

More broadly, national progressive organizations tend to confine themselves and their self-perpetuating organizing to the major cities, often on the East and West coasts, while wondering why the folks in the "flyover" states are so ignorant or so backward, and just don't understand the need for radical change. Perhaps if they did more outreach to folks in more difficult or isolated political circumstances, they could both expand their reach and begin to break the apparent conservative log-jam in U.S. politics, and start moving the political culture in a progressive direction. In the bargain, they might also learn a few things.

"It's pretty scary down here," says Madeleine Crozat-Williams, a Code Pink organizer in Houston. "We're sitting in one of the most conservative Bible Belt areas in the country. We feel like we hear shreds of the conversation about where to go from here, but we're struggling. We could use all the help we could get." ![]()

Oops! The following correction ran in our July 8, 2005 issue: In last week's article "Not So Red," the photo of Judge Charles McMichael should have been credited to Rose Aguilar, and the photo of the Rev. Jim Rigby should have been credited to John Anderson.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.