UT & Lockheed Woo Los Alamos

Peace activists urge UT to take a moral stand against weapons of mass destruction by refusing to bid on Los Alamos, while supporters see an opportunity for UT to increase its recognition and prestige, and protect national security

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., May 27, 2005

Somebody order a missile-shaped box of chocolates: The University of Texas' on-again, off-again romance with Los Alamos National Laboratory is officially on. After nearly a year of waffling, UT has decided to partner with Lockheed Martin, the nation's largest defense contractor, to bid on the Department of Energy contract to run the trouble-prone lab, one of three where U.S. nuclear weapons activities take place. Peace activists are urging UT to take a moral stand against weapons of mass destruction by refusing to bid, while supporters see an opportunity for UT to increase its recognition and prestige, and protect national security to boot.

But what exactly goes on at a nuclear weapons lab in 2005? After all, the United States hasn't produced new nuclear weapons since the Eighties, and hasn't conducted any tests since 1993. Still, there's something going on at that 40-square-mile facility in northern New Mexico – and both bid supporters and opponents argue that understanding that something is key to why UT should, or should not, be involved.

First, the basics. Los Alamos has been managed since its World War II-era inception by the University of California. Last year, Congress decided to put the lab's management out for a rebid because it starts to look kind of funny when a single entity holds the same government contract for half a century. Plus, a series of security lapses was making the place look like a joke – one that got even worse when a Los Alamos employee blog showing widespread dissatisfaction percolated into the media. UC is one of three announced bidders on the job; the others are UT/Lockheed Martin and defense contractor Northrop Grumman. The contract could be worth up to $79 million – 10 times more than UC's current $8 million management fee.

UT does not intend to actually manage the lab – they'll leave that to the friendly folks at Lockheed Martin. Instead, the university proposes to provide academic oversight on peer review processes and unclassified research, and help with professional development and educational programs. In return, UT will receive part of the management fee; but the real payoff, as system chancellor Mark Yudof told the Board of Regents, comes from "the opportunity to fully evaluate, restructure, and reinvigorate the work of our largest and, arguably, most important national laboratory." In fact, Yudof said it was UT's "duty" to offer its expertise to the lab.

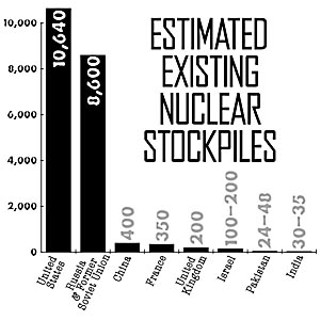

The "national duty" argument is popular among those who support the bid. As long as the United States has a weapons stockpile, the argument goes, ongoing research and maintenance is necessary to keep that stockpile safe. The U.S. has a serious stockpile – the biggest in the world, estimated at about 10,640 weapons, down from a peak of just over 30,000 in the late Sixties. During the height of the Cold War, the U.S. was constantly building new weapons, such that there was a "turnover" in the stockpile every 20 years or so. Now those weapons are just sitting there, untested and unused. This has its downsides – Brian Wilkes of the National Nuclear Security Administration compares it to having a car that sits on blocks in your garage since the Seventies. Responsible management, he said, means "you'd want to do certain things to make sure you could drive that car if you ever had to, God forbid."

About 60% of the lab's $2.2 billion budget goes toward "defense;" most of that is work known as "stockpile stewardship" – researching what happens when weapons age, making sure existing stockpiles are in good condition, and replacing worn-out or outdated parts. Wilkes pointed out that some of these upgrades replace toxic, old materials with less-toxic new ones, resulting in – drumroll, please – a more environmentally friendly nuclear bomb. ("I know it sounds funny," Wilkes said.)

The United States is a signatory to the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, which was first signed in 1968 and now has 190 signatories. Under the treaty, the U.S. can't produce new weapons, and is technically committed to eventually getting rid of its entire stockpile (although the treaty defines no timeline for doing so). If you have an old weapon and start gradually replacing all the parts with upgraded ones, however, at some point it starts looking like a whole new weapon. As such, nonproliferation experts fear that stockpile stewardship is starting to cross the line into weapons development. This is particularly true when it comes to a brand-new $9 million pilot program, partially conducted at Los Alamos, to explore the feasibility of something called reliable replacement warheads. RRWs – if they are ever put into production – would have an entirely different design from existing weapons, and as such would constitute the next generation of nuclear weapons. "The nonproliferation treaty doesn't say we should manage our stockpile, it says we should make a good-faith estimate to dismantle it," said journalism professor Bob Jensen at a forum exploring UT's involvement.

Wilkes denies the RRW program is a "backdoor way" to get around NPT. As U.S. officials use the five-year review of the NPT playing out in the United Nations to try to halt nuclear efforts by Iran and North Korea, however, other nations are using it to express concerns about our fulfillment of our own treaty obligations.

Such policy questions lie well outside of Los Alamos' purview. And as supporters of UT's potential involvement in the lab point out, plenty goes on at Los Alamos that isn't weapons work, from nuclear power to computer science. Plus, the end of the Cold War means nuclear threats can come from individuals as well as states – in other words, the Los Alamos budget includes harder-to-criticize activities like developing technologies to detect "suitcase bombs" or help secure poorly guarded nuclear materials and technologies in the former Soviet Union. It's these sorts of activities that make UT's potential participation in Los Alamos a complicated question. "The unfortunate fact is that you can't unlearn about nuclear weapons," said UT's Physics Chair Roy Schwitters. "They're out there. And they're dangerous."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.