Here Today, There Tomorrow

Austin ISD schools grapple with high student turnover – and all its consequences

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., March 11, 2005

On a clear, fall Friday afternoon, a group of teachers from Ridgetop Elementary school, at 51st Street just off Airport, pile into principal Joaquin Gloria's sparkling white SUV and ride across Airport Boulevard to a trio of apartment complexes on Harmon Avenue, a couple of blocks away. Armed with clipboard lists of addresses, they break into groups of three and, with the muted rumble of nearby I-35 as background music, begin knocking on doors. As many AISD teachers do, they are participating in a neighborhood walk to meet their students' parents, and talk with them about their concerns.

That is, if they can find them.

Principal Gloria takes the downstairs apartments, and the second group climbs up, occasionally glancing back uneasily at a slovenly woman hollering at the men who surround her balcony in the neighboring complex. As he approaches apartment 105, Gloria explains that most Ridgetop parents wouldn't choose to live here at all, if it weren't for one thing: on Harmon Avenue, a 600-square-foot, one-bedroom apartment runs $450 a month. Except for the first month: that's $99.

"I think they moved," remarks Gloria, before he even knocks on the door of Apt. 105. The parking lot is empty. On the blue paint of the door, someone has scrawled in black marker, "No tochin may dorr." Nevertheless, Gloria knocks a few times and waits. A few moments later, the other teachers tromp down the stairs. The family they sought, a neighbor told them, has also moved. "That's what they do," Gloria shrugs. "As soon as they can afford something better, they leave."

Internal Migrations

Among the many challenges facing Austin schools, outdated address lists may not seem like a big deal. After all, the students Gloria and staff were looking for had moved to another complex in the Ridgetop attendance zone without missing a day of school. But to schools like Ridgetop, where 89% of students are economically disadvantaged and nearly all live in apartments, mobility is actually a huge deal. In 2002-03, the last year for which data is available, the school had a mobility rate of 27% – meaning that more than one in four Ridgetop students moved in or out over the course of the school year.

"They go for all kinds of reasons," says Gloria. "Some go to Mexico for Christmas, and don't come back. Or they go for Christmas and come back in March. Some spend a few months here, and then their parents find work in Del Valle or Pflugerville, so they move up there, and then we get them back after six months or a year."

And Ridgetop is by no means the only AISD school whose front door briskly revolves. AISD as a whole has a mobility rate akin to Ridgetop, of 26.5%; but the rates at individual campuses vary dramatically. In general, the more affluent the school, the more stable its kids. To compare only elementary schools: At Casis, an "exemplary" school in Northwest Austin, mobility is 4.4%. Highland Park, another exemplary school in Northwest, has a 2.6% rate. But at Blackshear, where 96% of students are economically disadvantaged, the mobility rate is 34%. At Harris, in Northeast, the rate is 38%. And topping the charts is Linder in the Southeast, with a rate of just over 40%. In low-income parts of town, things are just as bad at middle and high schools.

Some school authorities point to "stability" rates – which reflect the percentage of students remaining at one school – as suggesting that the situation isn't as bad as it seems. That's true to a degree – but taking into account the difference between "mobility" and "stability" rates also shows how some families are even more strongly affected than these stark mobility statistics suggest. Under Texas Education Agency guidelines, a school counts one of its students as "mobile" if that student was at the school for less than 83% of the year – that is, if he or she missed more than six weeks. Using that data, the mobility rate simply divides the number of mobile students by the total number of students enrolled in a school at the course of the year: 45 of the 247 students enrolled at Ridgetop in the 2002-03 school year missed more than six weeks.

This is a different concept from stability, which neither the TEA nor the district currently tracks. Imagine a school with 100 desks, and 99 of them are occupied by students who stay in school from the first day of school to the last. However, in that last desk, 51 separate students come and go over the course of the year. That school would have a stability rate of 99%, but a mobility rate of 34%.

In other words, what the stability rate doesn't capture is the fact that many of the kids who move don't just move once: They ping-pong from school to school as their parents change jobs, share custody, or chase affordable rent. "We just had a family move for the fourth time," said Maria Martell, parent support specialist at Ridgetop. "We tried to help them, but they came up $100 short on rent. So now they're in their fifth school this year."

People don't just move because they like a change of scene. Even though $450 is well below the median apartment price of about $800, it's still a stretch for those making minimum wage or slightly more. A 2004 report by the Community Action Network, which studies affordable housing in Austin, found that 30% of female-headed households with children earned less than $15,000 annually. That puts affordable rent at $417 a month. While some subsidized housing is available, the waiting list for government-subsidized ("Section 8") complexes tops 5,000 families.

For some of these very-low-income families, moving from complex to complex to take advantage of move-in specials becomes a way of life. Because breaking a lease doesn't come with immediate consequences, families can sometimes bounce along for quite a while, especially in a slow rental market. The consequences come later. "When you break a lease, it goes on your credit report," said Katherine Stark of the Austin Tenants Council. "It won't be a problem when the market is slow, but when the market does tighten up, people call us crying because no one will rent to them."

However, not all movers are single-income families at the very bottom. Some working families scrape by all right paycheck to paycheck – until the unexpected strikes. Maybe dad gets sick and can't work for a week. Maybe a building job runs over schedule, and the contractor won't pay anyone until the very end, even though you're accruing late fees every day you miss your rent payment. Maybe someone gets sick and you don't have insurance, or dies and you have to pitch in for a funeral. Maybe a restaurant goes out of business and everyone gets stiffed out of their last week's pay. And finally, some movers are simply victims of bad-apple property managers, especially if they're immigrants with poor English skills.

"Sometimes landlords will charge immigrants different fees than [other tenants], or unfairly charge them for repairs," said Vielka Ridley, the parent support specialist at Travis Heights Elementary, which has a 26% mobility rate. (Despite its tony location, nearly three-quarters of its students are economically disadvantaged, many from a large Section 8 complex across from Travis High School.) "They do that knowing very well that many immigrants will be afraid to challenge them. They'll say, 'What documents do you have? You really don't want to take this any further.'"

In short, the reasons for mobility are as diverse as the people who live through the moves. But to Principal Gloria, student mobility is something schools must learn to address. "Maybe it's the $99 special," he said. "Maybe they found a place that's a little bigger, so two families can share. Maybe there are custody issues, and students are living with one parent and then the other. Or maybe there is a murder in your complex. It's just never-ending."

Mobility Breeds Mobility

Addressing the "never-ending" problem of student mobility means defining exactly what the problem is. After all, the same factors that increase your likelihood to move – basically, poverty – are likely to make you have trouble in school even if you don't move. "In general, being poor matters more than being mobile, but mobility does have an impact," says Ed Fuller, a professor of education at UT.

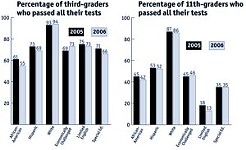

The TEA hasn't studied the issue since issuing a student mobility report in 1997; however, that study found that mobile students had lower test scores than stable ones. "On average, the less frequent the mobility, the better the student performance," the study found. "Stable students performed better than those who moved once, who in turn performed better than those who moved twice, and so on."

The study didn't control for the chicken-and-egg factor of whether mobile students have lower scores because a larger percentage of mobile students are poor. But Russell Rumberger, a professor of education at UC-Santa Barbara, says studies exist linking mobility to poor student performance, even if you control for socioeconomic status. He said the link is particularly obvious in high school, where it's been documented that mobile students are at a greater risk for dropping out, no matter their families' incomes. However, he says it exists in lower grades as well. "There's just the whole disruption factor," he said. "Change is hard."

If mobile students have more trouble academically, this is something that many parents find troublesome in the high-stakes, accountability-based environment of today's schools. Among the litany of complaints voiced by the anti-test crowd in AISD schools is that their schools' ratings are affected by the hypothetical kid who "had to take the test even though he just enrolled yesterday." After all, they say, test scores are supposed to measure a school's progress in teaching the children, and it's unfair to evaluate a school based on the performance of a student the school hasn't had a chance to teach yet.

However, the TEA does take this into account by using a "snapshot date" in October to determine which students' test scores count towards a school's overall ratings. A student who enrolls in Ridgetop the day before the TAKS test, for example, still has to take the test, regardless of whether he moved from Travis Heights or Kazakhstan. However, his scores won't count toward Ridgetop's ratings because he wasn't enrolled at the end of October.

But if the role of schools is to create educated citizens – not just to jump through some annual testing hoops – the real concern isn't what mobility does to test scores, but what it does to students. So, whatever the precise nature of the relationship between poverty, mobility, and academic achievement, it's fairly obvious that adding mobility onto an impoverished childhood makes a bad situation worse. AISD schools aren't simply classrooms; they're gateways to a whole slew of resources for students and families: testing and placement in special education or gifted and talented programs; vision and hearing exams and treatment; even basic needs like food and clothing. So for a student in the midst of, say, a diagnosis of a hearing disorder, moving from school to school can disrupt the whole process. "When students are moving from school to school to school, sometimes their folders just don't catch up," said Gloria.

Rumberger argues that mobility hurts more than just the mobile student. In recent years, the hot idea in schools is that building "relationships" between students, teachers, and parents is the key to improving low performance. This is the idea behind the role of parent support specialist at many AISD schools, behind a drive within the district to use mentors and stipends to reduce teacher turnover, and behind a "redesign" of all AISD high schools into smaller learning communities. But it's hard to build relationships, to say the least, when a quarter or more of your students come and go every year, especially when it most often happens at schools where teacher turnover is also high. At Blackshear, for example, 66% of the teachers have less than five years of experience.

"Teacher attrition and student mobility are linked," says Fuller, the UT professor. "Precisely the schools where you need a stable teaching force are precisely the schools that don't have them."

In other words, mobility helps breed mobility, and stability breeds stability. A teacher who is thinking about quitting may be swayed because of a personal commitment to a couple of favorite students. A parent may keep her child enrolled in a school because of a favorite teacher or because she can't imagine separating her children from their longtime buddies. But if too few people are staying put for those kind of relationships to develop in the first place, it's hard for people in revolving-door schools to see the value of staying put – indeed, at some schools, there may be no value.

On the other hand, even when schools forge strong relationships, the economic realities of renters' lives means that sometimes the desire to stay just isn't enough.

Churning Families

Teresa Ibarra is exactly the kind of parent you want at your kid's school. She showed up for every after-school event at Travis Heights Elementary. She cooked tamales for every fundraiser. But then her rent took a dramatic increase. Things in her apartment started breaking and stayed broke. The cold water didn't work in the bathroom, so the family would have to haul it around in buckets to take a bath. Finally, the single mother, who speaks little English, found a cheaper, better apartment in Pleasant Valley.

At first, Ibarra continued to drive her children to Travis Heights around her shifts at HEB. But even with some teachers pitching in with occasional rides, it became too much. About two months into the school year, she enrolled her kids in their new neighborhood school, Rodriguez Elementary.

"They cried a lot that day," she said. "They like Travis Heights because they had studied there since kindergarten. And the principal and teachers are great. They worked hard to help us, and everyone worked together to unite the school." The trust that Ibarra and her family developed with Travis Heights is exactly what many schools struggle to build. To Travis Heights parent Steve Jackobs, every lost parent and lost student adds to a sense of "churning" in the school that's counterproductive to its educational mission.

"I've seen the effects in my daughter's classes," he said. "Whether you're rich or poor or anything, the school will be better able to accomplish its mission when the kids are established and stable, and the relationships among them are stable, when the kids feel that this is part of their home."

To researchers like Rumberger, a major part of the battle is simply convincing parents of the value of sticking with one school, even if you have to move. But as Ibarra's experience illustrates, even parents who understand the value sometimes just can't afford it. To help these parents, then, some schools are going beyond and addressing the symptoms of mobility, and trying to treat the causes.

Fighting Back

Addressing the issue of mobility comes in two forms: easing transitions for mobile students, and trying to keep them from moving in the first place. After all, some mobility will always exist. Some families will move from unsafe complexes to safer ones; some will stop renting and buy homes of their own. At Palm Elementary in Southeast Austin, for example, the 24% mobility comes from more and more students enrolling midyear as their working-class parents buy homes in the neighboring subdivision.

AISD has several policies to smooth these inevitable transitions. First, every school has IMPACT teams that assess new students' needs and try to get them settled. For low-income families, that includes connecting them with social services like the United Way.

In terms of academics, the district offers an "aligned" curriculum, through which every school covers more or less the same subjects at the same time. That way, a student who moves from Ridgetop to Travis Heights will hop immediately into subjects she recognizes. While this doesn't help kids who move from Austin to Del Valle to Lago Vista and back to Austin, it does help intradistrict transfers. "I think [an aligned curriculum] helps," said Rumberger, adding that many districts don't even see the issue of mobility as "their" problem. "Just recognizing that mobility is an issue is a step forward."

But some schools are going beyond simply helping families adjust to a move – they're trying to prevent moves in the first place. At Ridgetop, the staff calls landlords to help non-English speaking renters explain what's holding up their rent payments – for example, if a family that lives paycheck-to-paycheck is simply waiting to be paid for a job. While Gloria says managers' reception to their overtures has been "case by case," the school has had quite a few successes.

"At the beginning of the year, we had a family that was living in a van," he said. "We wrote a letter, and even had it notarized, explaining that this was a good family and listing all the places they were looking for work. Then Maria [the parent support specialist] found a resource to cover half their rent, and we found them an apartment."

In addition to these desperate scrambles to address emergencies, the school is trying to be proactive and build relationships with local managers in hopes that it will make them more flexible when residents do have a temporary emergency. After all, even though the rental market isn't as soft as it was a couple years back, Austin's occupancy rate, especially in low-end properties, is still just around 90%. Complexes that encourage stability can minimize vacancies, as well as save on the cost of refreshing units and constant advertising. After a man was stabbed to death outside one of the Harmon Avenue complexes in January, for example, Ridgetop officials, the neighborhood association, and several local property managers all met to discuss the obvious safety concerns. However, the conversation also opened the door to discussion about the connections between management policies, stability, and education.

To Edward Ochoa, the new manager of the Montecito, one of the Harmon Avenue complexes, stability is good for business. He boasts nearly 100% occupancy rates in the complexes he manages, and he says being involved with his residents' concerns, including educational ones, is one of the reasons. "It helps our residents know that we are in touch with them," he said. "One of the things I hear all the time from residents of other complexes is, 'They don't do anything. They don't fix anything.' When you're on top of things, they tend to stay more, because they know you're listening and not just collecting their rent."

The owners of The Heights on Congress, where many Travis Heights families live, also saw value in being school-friendly. They applied for a federal program to get tax credits for running after-school tutoring and computer programs in their rent-controlled complex. "It's a great marketing tool," said manager Marie Gonzalez. "We have our share of turnover, but most of our people stay put."

In short, both schools and complexes can play a role in addressing the issue of student mobility. In fact, in an ideal world, they'll reinforce each other, as people who see each other around the complex and at the school hold each other accountable to show up at the PTA meeting or ask why little Maria showed up at school with no coat when it was cold outside.

However, building this kind of community isn't easy. After all, what property managers are willing to do in a slow rental market is different from how they might behave when it tightens back up. In addition, when many school employees already feel overburdened with addressing students' educational needs and government testing requirements, adding families' housing needs on top may feel like that back-breaking straw. And finally, there's the political climate to consider, and the fact that many are starting to argue that what schools need is not stability, but change – through greater "school choice."

Help at the Capitol?

These are unstable times in Texas public education. Schools are grappling with a high-stakes testing bar that moves a little higher each year. Meanwhile, the consolidation of Republican power means more credence than ever before is being given to the idea that the key to reforming education is market dynamics. That is – the school-choice crowd argues – parents can improve their schools not by behaving as a community that together builds a successful school, but by being allowed to behave as consumers, who vote with their feet to pick the best school and leave less popular schools to wither away. However, the concerns voiced by teachers at highly mobile schools add complexity to already complex debates over both.

For one thing, even if some schools fight to hang onto every student, others are no doubt succumbing to the incentive within the testing system – unintentional as it may be – to let struggling children go be someone else's problem, rather than going the extra mile to help them stay. Plus, a drive within the Legislature to increase accountability may not adequately take mobility into account. Consider the main school finance and reform bill in the Lege, HB 2 (on the floor as of press time): It includes money to provide monetary "incentives" for teachers posted in particularly challenging schools or whose students do well on standardized tests. On the one hand, higher pay for teaching in challenged schools is an obvious way to encourage stability. But rewarding teachers for students' test scores is trickier: With so many students bouncing from school to school, it's hard, perhaps even misleading, to determine which teacher is accountable for which students' results, so you can hand out the checks.

Plus, the bill would also enable the TEA to send in takeover teams – perhaps third-party private subcontractors – for schools that are low-performing two years in a row. Because these schools are already the most likely to be suffering high turnover, it raises the question of whether introducing even more instability is really the answer.

Stability isn't the whole answer either – after all, AISD obviously has no shortage of stable students with rotten grades. But if Texas is going to try to provide a quality education for all students, even those whose parents' housing decisions aren't in line with the educational needs of their children, it is certainly one of the factors to consider. And considering it opens serious questions about whether education is really a product that can be bought ready-made, or a process that can only be built day by day, student by student, and family by family. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.