Money for Nothing

How to hit the contractors' jackpot in Williamson County

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Aug. 15, 2003

This is a story about the practice of government in Williamson County: about the letting of government construction contracts; about changes to the state's Local Government Code affecting such contracts; about public officials suffering from conveniently poor memories; about millions of taxpayer dollars expended with apparently lackadaisical oversight -- and about bubbling, epoxy-covered concrete floors.

Indeed, if it hadn't been for the "fisheye" bubbling of the epoxy-sealed floors of the new Williamson County Juvenile Justice Center, it is also a story that might never have become public. But since December, when the epoxy began to bubble, simple queries concerning the floor problems have multiplied and expanded to embrace a more significant riddle: whether certain of the county's elected officials are actually or effectively serving the taxpayers whose interests they have sworn to uphold.

Details, Details

A low-slung brick building surrounded by chainlink fencing and modest landscaping, Williamson County's new Juvenile Justice Center sits on a 179-acre tract of land off Inner Loop Road near downtown Georgetown. The facility was intended to house all of the county's juvenile-justice components -- the juvenile probation offices, juvenile detention center, and the Juvenile Justice Alternative Education Program. But more than a year after construction was scheduled for completion, the building remains unfinished, and is occupied only by the juvenile probation staff and the JJAEP's overnight residents. The problem, says Williamson County Attorney Gene Taylor, is that last November a flooring subcontractor, Austin-based Sunrise Commercial Painting, incorrectly applied an epoxy coating to the facility's concrete floors, causing the epoxy subsequently to bubble and requiring replacement before the facility is ready for full occupancy.

Taylor says the subcontractor didn't adequately prepare the concrete floor to ensure epoxy adhesion -- by using acid to roughen the surface. "Acid etching is what they tried to do," said Taylor, "and I don't think they did it adequately enough." Sunrise owner Nemesio Sanchez disagrees, suggesting instead that his company has become a scapegoat for the rest of the long-overdue project's problems. According to Sanchez, the county-hired construction manager, FT Woods Construction Services Inc., required him to complete the work despite indications of excess moisture rising through the porous concrete, preventing proper adhesion of the epoxy. (FT Woods says its records of the timing and circumstances of the epoxy application differ from those of Sunrise.)

Exactly when county officials learned of the floor problem is also a subject of debate. Sanchez insists he made general contractor FT Woods aware of his concerns in November but that the problem was not reported to county commissioners until this spring. County Judge John Doerfler says that FT Woods' representatives regularly updated commissioners on the project's progress, and Taylor says that although he hasn't "seen every paper," he knows the company kept exhaustive daily logs detailing the job's progress. Yet county commissioners first addressed the epoxy issue in April, and did not act on remediation until May, less than a month before the already-delayed project had been scheduled for completion. (In July, the court awarded another subcontract, this time to re-cover the floors permanently with a combination of tile and carpet.) Taylor says the county has also hired an outside expert to test the flooring and determine whether Sanchez's claim that underlying moisture and not inadequate preparation was the root cause of the flooring problem. "We hired a testing expert to affix blame," Taylor said. "In all likelihood there will be a lawsuit."

FT Woods says it told county officials in November that the epoxy might not work, and "it would be prudent to have an option for installing other flooring," but the county decided to proceed with the original plan. According to FT Woods, in order to get the epoxy installed, Williamson County "relieved [Sunrise] of their warranty responsibilities from moisture," and the installation began. (At press time, the county had not yet received a report on the floor analysis.)

But the flooring controversy has generated much more than the obvious bubbling -- it has also raised numerous questions about the official county procedures in the course of awarding and negotiating the center's basic construction contract with FT Woods. In turn, the review of the Juvenile Justice Center deal has raised additional concerns about the contract procedures under which another project -- construction of an East Williamson County Special Events Center in Taylor -- was awarded to and negotiated with FT Woods last summer.

During the course of the nearly yearlong delay completing the juvenile-justice project, FT Woods has continued to receive more than $37,000 a month in compensation -- over and above the nearly $700,000 flat fee the company had already received to oversee the $19.9 million project. The additional payments were written into the county's contract with the company, but are supposed to be paid only if the job is delayed through no fault of the general contractor -- a determination that is yet to be made. As of mid-July, FT Woods had collected more than $411,000 in monthly late fees, payments the county auditor says currently are required under the contract. County officials say they expect a report from the outside expert soon, but would not say whether FT Woods may have to return any of the late payments if it is found to be at fault.

Representatives of FT Woods declined the Chronicle's request for an interview, but the company responded to a list of written questions, summarizing, "FT Woods Construction has consistently done everything in its power to look after the best interests of our client Williamson County."

Last spring, long before the center's floor problems became public knowledge, the Commissioners Court embarked on another project: the design and construction of the Taylor events center. That project was also awarded to FT Woods -- in large part because the company's bid package promised that the entire job, from start to finish, would be completed within six months. The Special Events Center project, which earlier this summer was still in the preconstruction phase, is now also behind schedule -- a five-month delay that has thus far netted the contractor an additional $15,000 in preconstruction late payments. And it appears that that $15,000 will be only a small portion of the money FT Woods will receive for its management of the $3.1 million project.

For the Juvenile Justice Center and Special Events Center deals, the Williamson County commissioners, county judge, and county attorney negotiated and signed off on construction contracts that diminish the county's oversight of the projects while adding a host of potential extra sources of compensation for FT Woods. When asked about the contractual details, county officials alternately claim they don't remember why or they don't know how questionable provisions made it into the contracts. The commissioner designated as the court's "point man" on both projects -- eastern Williamson County's Precinct 4 Commissioner Frankie Limmer, who owns a construction company himself -- declined to answer specific questions about the contracts, although he did say he believes "FT Woods Construction gave the county good value for the dollar spent."

The open questions about the contracts are rather basic: How were the deals put together; who was involved; and who, ultimately, stands to benefit?

Point People

The office of First Assistant Williamson County Auditor Bob Space is on the third floor of the old county courthouse in downtown Georgetown. Black marker in hand, Space sets out to explain the often-complicated county procurement process, by way of a series of circles and arrows drawn on a dry-erase board affixed to his office wall. Ordinarily, he says, the county has relied upon Chapter 262 of the state's Local Government Code to guide the process of awarding and negotiating county-funded projects. "The heart of what we do is in 262," he says. It outlines the process for "advertising [an upcoming job], collecting the bids -- the protocol is very well defined." The process is lengthy, extremely regimented, and time-consuming.

Over the years Texas lawmakers have tried to streamline the process, Space says, establishing several alternative provisions, mainly under code Chapter 271. In 2001, Chapter 271 was amended to create two new types of public-let construction arrangements: construction manager-agent, or "CM-A," and construction manager-at risk, "CM-R." (See sidebar, next page.) County officials say the Commissioners Court decided in early 2000 to use the amended Chapter 271 when letting the contract for building the Juvenile Justice Center and later for the events center, as well. By all accounts, that's where things first got complicated.

According to County Judge Doerfler, the court tapped Precinct 4 Commissioner Limmer, owner of Limmer Construction, to work with County Attorney Taylor on the selection of a construction manager and the contract negotiations for the $19.9 million juvenile-justice project. "A lot of the things that we do, we have point people on, and they take the lead, and they bring the contract back to us," Doerfler said. "Frankie Limmer was the point man." According to Taylor, on the other hand, as county attorney he's "it" when it comes to county contract negotiations. "I've done construction work before," he said, "so I've taken this on as my thing." Taylor and Limmer set out to find a construction manager to act as the county's agent -- a CM-A -- for the job and to negotiate the project terms with the CM-A. On April 18, 2000, Doerfler and FT Woods Construction Services Inc. President F. Todd Woods signed an initial contract for the juvenile-justice project.

But by that fall the county auditor's office, headed by David Flores, had begun to question exactly what type of contract the commissioners had intended to sign. To the auditors, it appeared the county was attempting a CM-R arrangement, but had also incorporated elements from the CM-A. More importantly -- although other states were already using either CM-A or CM-R arrangements under standard-form contracts -- those provisions had not yet been incorporated into Texas law, and wouldn't be until Sept. 1, 2001, a year and a half after the juvenile-justice contract was signed.

Moreover, in what may have been inconsistent with the standard procurement process, Limmer and Taylor had also selected the FT Woods company as construction manager without publicly advertising the job or releasing any kind of formal request for bidders. And although the standard-form contract that officials used to execute the deal indicated that the job would be done for a guaranteed maximum price, no GMP was listed. Instead, FT Woods was to receive as compensation 3.5% of the total project cost. On the face of it, that provision appeared to provide a direct incentive for the general contractor to inflate the cost of the overall project -- or at least provided no obvious incentive to keep the cost down.

Ultimately, by the fall of 2000, the auditors informed the commissioners that the contract as negotiated did not follow standard state procurement practices, in theory forcing county officials and contractor back to the drawing board. But they didn't start from scratch. Limmer and Taylor still avoided the open bidding process, keeping FT Woods Construction on board as the project's construction manager. Under the new contract, they hired the company for "professional services" -- a statutory job category that, loosely interpreted, meant the county could technically yet legally circumvent the public bidding process. On occasion, Taylor has said that FT Woods Construction was hired based on the company's "qualifications" and "reputation" -- the standards applied when selecting a project manager for a CM-A job. "They give us a level of confidence that others don't," Taylor told the Austin American-Statesman in June.

Yet Taylor himself acknowledges that prior to getting the Juvenile Justice Center gig, FT Woods Construction Inc. had apparently never before been hired to run any county-let construction job, in Williamson County or elsewhere. Once in progress, the project eventually came to the attention of other local contractors, one of whom told the Chronicle he didn't even know the county was building the facility until he drove by the site one day -- right past a large "FT Woods" sign.

On Feb. 12, 2001 -- still more than six months before the law governing the new types of contract would take effect -- Judge Doerfler and F. Todd Woods signed the second version of the Juvenile Justice Center contract. It wasn't until well over a year later -- when the problems with the floors became public -- that the other provisions of that contract got any public attention.

"Highly Unusual"

Under the terms of its new contract with the county -- negotiated because the auditor objected to the terms of the first one -- FT Woods was still poised to do very well -- indeed better. Thus far, county records indicate the company has received more than three times the amount of money that it could have expected to earn under the first contract. Although completion of the justice-center project is now more than a year overdue, FT Woods is still getting its monthly payment of more than $37,000, for a total of more than $411,000 just for the additional 11 months (as of July) that the project has remained unfinished. Asked what professional services the company was performing during that time, Taylor referred to the "punchlist" (a contractor's term for the checklist of items still needing attention at near-completion) and said, "It took a while to get the punchlist done -- who's supposed to come out and finish, what's [already] done. There have been things going on until recently -- we've been stalled until we get the testing [on the floors] done."

And that was just a slice of the contractor's package. In addition to the $696,000 base percentage (now calculated as 3.5% of the job's budget of $19.9 million), the second contract included a host of other potential compensations, including a flat fee of nearly $800,000 to compensate a list of 18 unnamed personnel the company identified as "potentially" working on the project. Under this provision, moreover, FT Woods would never have to justify the additional payment. "The Construction Manager does not intend to provide and shall not be required to provide the ... personnel on a full-time basis for the Project," reads the contract. "Which of the ... personnel and how much time each will devote to the Project shall be solely within the discretion of the Construction Manager."

The contractor has also received additional money for "reimbursable expenses": items FT Woods might have used -- for example, office equipment -- or additional procedures they might need to do at the job site, like a final cleanup. Again, under the contract, use of these items is left entirely to the discretion of FT Woods. "Which of the ... services, materials and equipment and how much time each will be utilized for the Project," the contract reads, "shall be solely within the discretion of the Construction Manager."

As of mid-July, according to county records, FT Woods had already been paid more than $2.4 million for managing the justice-center project -- three times what they could have expected to get under the first contract, under which they had also agreed to accept responsibility for all of the project's cost overruns -- a provision omitted from the revised contract (see "The Devil Is in the Details," above).

Blake Peck, a construction-contract expert and past president of the Virginia-based Construction Management Association of America trade group, reviewed the justice-center contracts and initially described both contracts as "kind of unusual." He went on to say a bit more: that the increased compensation package in the second contract is "extraordinary, a quantum leap. It's almost double [on its face] what they were willing to take when they were doing the job and being responsible for performance" -- that is, for all potential cost overruns. "It's highly unusual," Peck said, "to be paid large monthly fees for not doing anything."

Yet that still wasn't the end of it for FT Woods. Last year, while debate proceeded over responsibility for the bubbling floors and the contractor's hefty monthly compensation, official and public attention turned to yet another contract the commissioners had signed with FT Woods: for the construction of the East Williamson County Special Events Center in Taylor, the heart of Frankie Limmer's Precinct 4.

FT Woods says, "There is nothing in either project's CM contracts that is unreasonable or unusual. ... Statements have been made that there are provisions in these contracts that have given us an incentive to be late. Nothing could be further from the truth. ... The provision in question in the contract simply stipulated what the compensation would be rather than leaving it open for negotiation if the project was delayed for reasons beyond the control of FT Woods Construction."

Better Late Than Ever

In early July 2002, Judge Doerfler and F. Todd Woods signed another deal -- executing a contract for construction of the East Williamson County Special Events Center, intended for rodeos and other public events. The previous September, the new provisions of LGC Chapter 271 had taken effect, freeing the county to proceed under the new law. Under the events-center CM-R contract negotiated by Taylor and Limmer, FT Woods apparently stands -- once again -- to do very well indeed.

Last spring, when the justice-center construction was already under way but before county officials realized its completion would be extensively delayed, county officials set out to secure an "at-risk" construction manager to handle the events-center construction. In keeping with the CM-R letting process, the county issued a request-for-qualifications bid package. They got six responses, including a bid from FT Woods. A panel of six county representatives, including Limmer, Doerfler, and Space, evaluated the bids and chose Woods.

The FT Woods bid package was immediately attractive, says Auditor Space, because the company said they could complete the entire job -- from planning through construction -- within six months. The other bidders, he said, pledged completion within a year. "Keep in mind," he said, "we were looking at [the FT Woods proposal] and had no reason to believe [the justice center] wouldn't be in on time."

FT Woods got the job, but apparently it wasn't until this summer that anyone thoroughly reviewed the contract's provisions -- that is, until Woods' late-pay for the justice center turned heads and the auditor's office decided to review not only that contract but also the one for the events center (see "Chronology," at right). They found that even though Doerfler and Woods had ostensibly signed a CM-R agreement -- whose hallmark is the construction manager's "at risk" responsibility to absorb cost overruns, including those incurred through project delays -- negotiators had added a special provision, granting FT Woods nearly $26,000 a month if the project wasn't completed within the six months the company promised. The late-payment arrangement had, in effect, both undermined the ostensible reason for hiring FT Woods in the first place and removed at least some of the risk from the "at-risk" arrangement. In fact, the late-payment provision appeared to create an incentive for delay. The auditors -- who normally prefer to review the contract procedures and terms from the very beginning -- once again found themselves intervening after the fact.

"My concern, from a procurement standpoint, was that [FT Woods' initial bid package] had no reference to an add-on if they didn't get it finished," Space said. "There were other [bidders] who said [they'd complete the project within] 12 months and, 'If we don't get it done in 12 months, here's the [amount of] liquidated damages we'll pay.'" The discovery prompted Auditor David Flores to raise questions to the commissioners about the contract's potential late fees. That held up the court's planned June 17 date to give the final go-ahead for the events center's construction phase; on June 24, the amended contract -- now without the late-payment provisions -- got both the commissioners' and auditors' nod.

According to a June 24 article in the Statesman, Sonne Person, FT Woods' manager for the Juvenile Justice Center and Special Events Center projects, told the daily in an e-mail that the company had no problem with the county deleting the late-payment provision from the events-center deal. "There is no hidden agenda or secret plan to delay the project and collect additional compensation," Person reportedly wrote to the daily. "The set amount was simply included to prevent long drawn out disputes about the actual cost to FT Woods Construction for delays caused by others."

But the auditors are formally charged only with reviewing a contract for compliance with the law, not necessarily whether its terms constitute a good deal for the county. And a thorough review of the amended contract suggests that the revisions won't exactly lighten FT Woods' pockets.

Taylor and Limmer negotiated the events-center deal in 2002 based on Woods' assertion that the guaranteed maximum price for the job would be just over $2.9 million. FT Woods would receive a lump sum of $12,000 for preconstruction work and just over $116,000 in fees for the construction phase.

On that basis, county officials drafted and signed off on the entire deal -- before the design was completed and before FT Woods had solicited subcontractor bids, the two largest factors dictating project cost. Chapter 271's CM-R provisions require that a representative of the county oversee the subcontractor bidding process to ensure confidentiality and fairness and to offer the county an opportunity to have some say concerning the subcontractors. But in the events-center contract, all of the language outlining that dual control had been eliminated -- FT Woods was granted sole discretion over the choice of subcontractors.

According to sources in county government, FT Woods solicited subcontractors without any standard procurement controls, even though the company itself was apparently submitting bids. For example, one source says they accepted unsealed bids by fax and without adhering to any deadline, although the legal code requires confidential sealed bids submitted by a specific deadline. And while Chapter 271 allows the CM-R to bid on any or all of the subcontracting work, the law also requires that the general contractor do so in a manner consistent with rigorous procurement practices that the events-center bids reportedly lacked.

According to FT Woods, "the confidentiality requirements ... requiring that only the [Construction Manager] and the county see the bids until approval of the GMP were adhered to."

In any event, FT Woods returned to the commissioners with its chosen list of bidders, and with a new, higher GMP of $3.1 million -- a price the company said it would guarantee subject to the acceptance of its list of subcontractors. And the subcontractors' list included hiring FT Woods for three of the subcontracting jobs, for a total of nearly $1 million in additional work for the general contractor. The revised contract also contained other puzzling provisions, for example: 1) Any cash discounts received on construction materials would revert to FT Woods, although construction-contract experts told the Chronicle such benefits normally belong to the project owner; 2) should the project come in under budget, FT Woods will split the savings with the county -- a common provision -- but the company alone is responsible for the project's accounting records, which are available to the county only "upon written request." (For a summary of the Special Events Center contract's major financial provisions, see austinchronicle.com/news.)

Moreover, while the auditor's office had deleted the late-payment provision for FT Woods on construction-phase services, auditors had failed to delete the same provision for preconstruction work. That apparent oversight has already netted Woods an extra $15,000.

The Way Things Work in Williamson County

Independent experts asked to review the various FT Woods contracts say they consider the questionable provisions, at best, "unusual." "The county is letting [this happen]," said Bruce D'Agostino, the executive director of the Virginia-based Construction Management Association of America. "I'm really disturbed that you have someone calling themselves a professional company that is [involved with these contracts]. But who's watching over this? Who's on guard?"

According to County Judge Doerfler, Taylor and Limmer were in charge -- and presumably, protecting the interests of county taxpayers. Although the judge's signature appears on both the contracts and on all of the payment invoices FT Woods has submitted to the county, Doerfler says he's never thoroughly read the contracts in question. "We [on the Commissioners Court] look through [the contracts] briefly, but not thoroughly, and we take [Taylor's and Limmer's] word for it that it's the best deal for the county," he said of the Juvenile Justice Center contracts. And he admits that he has never read -- not even "briefly" -- the contract for the Special Events Center. "No ... I've not," he said. "I'll admit, I've not."

Doerfler says he "can't answer" any questions about why or how FT Woods ended up with such a rich compensation package, but, he says, "as far as I was concerned" they were both "good deals" for county taxpayers. When pressed, Doerfler now says, "There are things in [the contract] that I know about now that I thought the county attorney would've caught."

County Attorney Taylor agreed that he and Limmer were in charge of awarding and negotiating the contracts but said he couldn't answer questions about specific provisions. Taylor said only that he "can't answer" because "I don't know." But Taylor still insists that county taxpayers have gotten a good deal for their money. "Yeah," he said. "I am confident in dealing with FT Woods." FT Woods wrote, "FT Woods Construction is proud of the work we have done for Williamson County. We are proud of the Juvenile Facility. ... FT Woods Construction has consistently done everything in its power to look after the best interests of our client Williamson County."

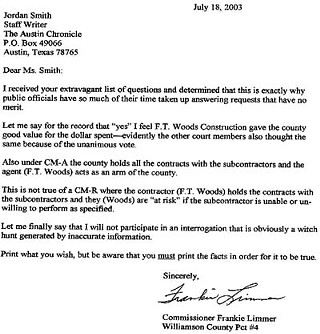

That leaves Commissioner Frankie Limmer, who declined several requests for a personal interview but initially said he would be willing to answer a list of written questions. When we supplied a detailed list of questions addressing the projects, the contracts, and the county's procedures in letting them, Limmer declined to answer any of the specific questions. In a faxed one-page response, Limmer said he thought FT Woods "gave the county good value for the dollar spent," and "evidently" the other members of the court did, too, since they voted to accept the contracts. Limmer dismissed the Chronicle's "extravagant list of questions," adding "that this is exactly why public officials have so much of their time taken up answering requests that have no merit."

"Let me finally say," Limmer wrote, "that I will not participate in an interrogation that is obviously a witch hunt generated by inaccurate information."

The official county response -- or rather, the lack of response -- doesn't surprise longtime Williamson County resident and government critic Melissa Shea, who sits on the board of directors for the Texas chapter of the public-interest watchdog group Common Cause. "The Commissioners Court are just the biggest bunch of good old boys you've ever seen," she said. "The way things work in Williamson County is that if it's a good deal for your buddy, it's going to get done."

Commissioner Limmer is proprietor of his own construction company, Limmer Construction, and prior to his election to the court, had dabbled in real estate development. According to county deed records, Limmer has bought directly, or through a family trust created with his wife in 1993, large parcels of land and has also bought and sold numerous residential lots within various subdivisions -- most within eastern Williamson County, the area he now represents on the court.

Since joining the court in 1999, Limmer's real estate interests appear to have expanded from retail to wholesale. He has formed a network of business entities -- mainly limited liability partnerships and companies -- each primarily concerned with large-scale real estate development, including at least two new Taylor housing subdivisions, Rob Roy and Mustang Creek. Some of the other county officials also have development interests, but in his real estate acquisition and development activities since 1999, Limmer has apparently outpaced the other commissioners, county judge, and county attorney combined. And Limmer's personal economic connection to the future of the precinct he represents grew exponentially with the formation last summer of his most adventurous business partnership to date: Magellan Water LLC.

Limmer formed Magellan last July for the purpose of building a $30 million water pipeline fed by the relatively untapped and massive Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer, which would supply water and support more development in his precinct. Limmer has declined to name any of his partners or investors, a refusal which critics say conceals potential conflicts of interest, since Limmer's official position offers him access to privileged information that could give Magellan an advantage over potential competitors (see "Commissioner Limmer's Private Business," p.30).

Since the late-payment construction provisions were deleted from the Williamson County Special Events Center contract in late June, county officials have said little else about either of the projects -- aside from reiterating that they are good deals for county taxpayers -- and county officials have apparently returned to business as usual. On July 29, the court voted to approve a request by Limmer's family to create a water-control and -improvement district on 547 acres of undeveloped land near Hutto in Limmer's precinct, land owned by the Limmer Family Trust. The move would protect the land from any future development regulations, offer tax-exempt financing options for Limmer and his family, and guarantee their ability to supply water to the property. According to the Williamson County Sun, Limmer recused himself from the court's recent discussion and vote, and he told the Statesman last month that the proposed district "will not be connected to [use] by Magellan Water LLC."

Common Cause's Shea says the absence of any continuing Williamson County community outcry in response to the insider approach to business at Commissioners Court doesn't surprise her. "That's what always [happens]," she said. "The tenacious people eventually just wear out. People get burned, and burned-out."

County Attorney Taylor, on the other hand, strongly disagrees with any suggestion of official impropriety. "Right now, everyone thinks everybody's doing something wrong, and I don't think that's true," he said. "The only way you're ever going to eliminate that is to involve every single taxpayer in every single government decision, and that's just not possible." The commissioners have been taking a lot of undeserved heat over the two major projects and the underlying contracts, Taylor insists. "Frankie Limmer, for example, gets flak around town," Taylor said, but "he's done an outstanding job as a commissioner because he's in construction and he knows construction; he knows what they're doing."

"Instead of being condemned," Taylor concluded, "he should be commended." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.