Raped Twice?

Virginia Glore Asked the APD for a Rape Test -- Instead, They're Prosecuting Her for DWI

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Oct. 12, 2001

Virginia Glore sits in a plastic chair on the patio of Hill's Cafe, her legs drawn up underneath her, alternately smoking a cigarette and nibbling on a serving of pork ribs. The 37-year-old mother of four is a shy, slight woman, with an unmistakable air of vulnerability. Glore says she leads a fairly quiet life, raising her children -- who range in age from five to 15 -- and waitressing full-time at Hill's. Her daily and weekly life is ordinarily very routine -- that's partially why what happened to her on Aug. 4, 2000, and its continuing aftermath are difficult for her to comprehend.

What began as a routine Friday payday -- "a mom's afternoon" with her best friend Charlotte Hughes -- turned into a fractured evening that, to this day, Glore barely remembers. By 11pm that night she'd totaled her husband's rare, "cherry" Ford Thunderbird, smashed out the rear passenger window of an Austin Police Department squad car, and landed herself in the Travis County Jail on a charge of driving while intoxicated. That wasn't all -- indeed, that was far from the worst.

The next day Glore awoke, or came to -- Glore says she doesn't know which it was -- in the city's central booking facility. Hughes picked her up, and brought more disturbing revelations. "When I got in the car with Charlotte," Glore remembers, "the first thing she says is, 'Girl, we were drugged.' When she said that, I started to shake. I could feel it in my gut. I said, 'I want to go to the hospital.'"

Even before Glore left the jail she had begun to realize that something was very wrong. She was bruised, cut, bloody, and burned. Her fingernails were torn, her clothes filthy and her underwear stained -- and she didn't remember how any of this had happened. She says she had flashes and impressions -- for example, looking at the round cigarette-like burn she discovered on her foot while still in a holding cell. "I realized that I had a round burn on the top of my foot," she said. "And every time I look at it I get this impression of people going, well, 'How will she react to this?' And then someone burning me. This is an impression; I don't know if it's what happened, but it is the impression and the feeling that I get every time I see it." Impressions and feelings, along with the soiled underwear and her numerous cuts and bruises, were all Glore knew of what had happened that August evening. For her, the empirical evidence dovetailed into an inevitable conclusion: Glore became convinced that not only had she been drugged, but that she had also been raped.

When Glore arrived the next evening at South Austin Hospital, she told the emergency room staff what she believed had happened, and asked that the staff give her a rape kit test and a toxicological screen. "The tox screen was especially important to me," she said. "Then I felt I could prove that I had been drugged, that all of this had happened." The ER staff alerted the APD that Glore wanted to file a report and that she wanted the tests -- standard operating procedure in rape or sexual assault cases.

The officers who responded to the call from the hospital took her report and called it in to APD's sex crimes unit, she said, but when headquarters radioed back, Glore was horrified. The officers told her they knew she'd spent the night in jail on a DWI, she said, and moreover they believed she was fabricating the whole drug and rape story in order to evade the misdemeanor charge. In short, the APD explicitly denied Glore access to the rape kit test and the tox screen -- even after Glore said she herself would pay for the exams. Glore's medical report from South Austin Hospital confirms her story. "Also noted APD was here," reads the ER report, "and they felt that this patient's story was fabricated, that she has this lapse in memory and they think this is just all a scheme to get out of her DUI [sic]... They [APD] are not going to approve of [the] rape exam, and they are not going to take her to the SANE [sexual assault nurse exam] nurse at St. David's."

A few days later, Glore realized that the Travis County Attorney's Office intended to prosecute her on the DWI charge. The county attorneys shared the cops' judgment: that the rape allegation was merely a ruse to avoid a DWI charge. "There is credible evidence to proceed with the DWI," said Travis County Attorney Ken Oden. "Her claims of [involuntary] intoxication are incredible." APD Commander Duane McNeill, who oversees the department's Centralized Investigations Division, insists that Glore's rape case is still under investigation -- and that at least two suspects have been cleared. But their investigation of the incident appears to have been cursory at best.

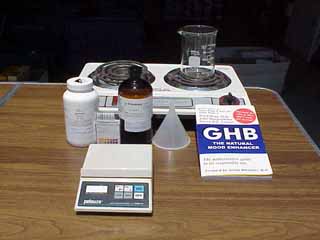

If so, it is a puzzling oversight, because what Virginia Glore and Charlotte Hughes say happened to them is hardly "incredible." Nationwide, drug recognition experts, law enforcement agents, rape crisis counselors, medical personnel, and prosecuting attorneys are becoming increasingly concerned about the use of drugs -- most notably Rohypnol and GHB -- to facilitate the crimes of rape and sexual assault. Experts admit that widespread use of the drugs is relatively new and that tracking them -- when rapes and sexual assaults are already underreported -- is not easy. Moreover, Rohypnol and GHB are relatively easy to come by (GHB can be made at home with chemicals readily available over the Internet), are extremely difficult to detect in any standard toxicological screening, produce symptoms similar to alcohol intoxication, and leave their victims with "antegrade amnesia" (no memory of recent events).

The task of investigating the use of "date rape" drugs, not to mention apprehending and prosecuting the perpetrators, is very complicated. "This is a really big problem," said Tracy Bahm, senior attorney with the American Prosecutors Research Institute, an arm of the National District Attorneys Association. "Already rapes are underreported. Maybe 25% of all rapes are ever reported to law enforcement. Add to it the drug-facilitated factor ... we just aren't really even sure how many there are, but we know that the number reported [is] an incredibly small fraction of the number that occur."

All of this taken together, said Jim Mock, a former Torrance, California police officer turned nationally recognized drug recognition expert, can hamstring law enforcement agencies if their staffs are not trained -- or willing -- to recognize and investigate such crimes. "The whole situation is a mess," said Mock. "A lot of people aren't trained, because they don't see this as a problem. Ignorance is bliss. But I've got a bombshell for you. If you think these are the only two girls in Austin that this has been done to, you're wrong."

Sixth Street Flashbacks

During the summer of last year, Virginia Glore and Charlotte Hughes were roommates. Both worked full-time as waitresses at the UT Stadium Club, and between them, they were raising seven children. The two friends seldom had occasion for much of a social life. "We would just stay home mainly, except for these every other Fridays," Glore said. "We did this for about four months, before all this happened in August." The two women would finish their work at the Stadium Club, then head down to Sixth Street. They'd stop by the 24-Hour Store near Sixth and Brazos to cash their paychecks, then head across the street to Jazz and have a couple of drinks -- Bermuda Triangles, which are rum drinks with three shots of rum -- and some appetizers, usually oysters. "This was just a Friday tradition," Hughes said.

On this particular Friday, the two women deviated from their routine. That morning Glore had driven her husband's rare 1988 retro T-Bird to work and then down to Sixth Street, something Allan Glore -- from whom she was separated at the time -- did not like her to do. "That was such a nice car, and really rare. There were only like 3,000 of them made," she said, "and he did not want me taking it down to Sixth Street." After two drinks, the women left Jazz -- and were coming out of Forbidden Fruit, where they had stopped to browse, when Hughes said she thought she saw Allan drive by. Since the T-Bird was parked in front of Jazz, right on Sixth, Glore and Hughes figured Allan had seen the car and would loop back around to try and find them. "I thought, well, he's going to be pissed about this," Glore said. "I thought he'd go check [inside] Jazz and then he would go wait by the car, and we would just go home with him."

Because it was just after 5pm under the harsh August sun, the friends decided to slip into the Aquarium bar, across the street from where the car was parked, to wait for Allan. The bar, Glore and Hughes said, was pretty dead. Other than a group of men sitting at a round table near the front, there were only two other patrons: two men sitting at the end of the bar. A single bartender was serving drinks. "We sat down and started talking to the bartender," Hughes said, and they ended up ordering two Rum Runners. "This was also kind of like a post-birthday celebration for me," she said. "My birthday was on the first and I didn't get to celebrate then." Hughes said Glore told the bartender about Charlotte's birthday, and he moved to the other end of the bar, standing in front of the two men who were sitting there, and prepared the women a complimentary birthday drink he called a "Purple Passion," a fruity vodka shooter.

When the bartender returned, Hughes said, she drank her shot and Glore drank part of hers. Glore went to the bathroom, and then called her kids. She told them that they would be home in a while, that they were waiting for Allan and would probably be coming home with him. When Glore returned to the bar, Hughes rose to walk to the bathroom, Glore said.

"Here I get a little fuzzy," says Glore. She remembers that as Hughes walked toward the bathroom, the two men from the opposite end of the bar stood up and moved toward her. "I didn't really pay too much attention, but I remember one guy moved behind me, as if to go to the bathroom -- and I don't know whether he stopped or not," she said. "I know the [second] guy was talking to me -- he sat within one bar stool and swiveled toward me. I swiveled toward him as he was talking, so my back was to where the other guy would've been, and partially away from the bar."

Meanwhile, Hughes says, when she entered the bathroom, she realized something wasn't right. "I went into the bathroom and my eyes were looking funny, and I just didn't feel right," she said, "but it wasn't like being drunk. And at the time -- I mean, I am six feet tall, and at the time I weighed like 250 pounds, and so I knew I wasn't drunk from what I had had. But I just did not feel right."

Hughes says she left the bathroom determined to leave the bar. "At this point Jenny [Glore] wasn't Jenny any more," she said. "She was being too overt, and she couldn't even sit on her bar stool without falling." Glore was still talking to the man on the adjacent bar stool. "I got her to quit talking to the guy, and we got out onto the street," Hughes said. "And I hear someone calling from behind and it was those same two guys, asking if we needed any help."

For Glore, even this segment of the chain of events is blurry. "My next memory is of getting off the bar stool -- it's not really a memory, more of an impression -- and walking into the blinding sunlight," she said. "We were walking toward the car and a voice called out from behind us, and that's all I remember." Hughes remembers a little more, but not much. She remembers the men approaching them near the car -- she later gave a description of the men to police -- and she remembers going with them into yet another bar, the Daiquiri Factory, where the men ordered them a drink rum drink called Ecstasy "I don't remember if I drank it or not," Hughes recalls, "and I don't remember leaving or getting into the car."

Neither of the two women have a coherent memory of what happened next. Hughes remembers a few moments, most notably of being in the car and getting sick. "I remember going down the highway, I-35 I believe, and [I] stuck my head out of the window to throw up," she said. "It was still light out at this time. I was sitting in the back seat by the window, and Jenny was sitting in the middle part of the back seat. I don't remember seeing how many other people were in the car." The rest comes in flashes, she said. Standing by a Coke machine arguing with two men; a flash of being in the car; the engine revving, an impact, then hitting her head against the dashboard. "Then," Hughes said, "I just blacked out."

The APD Investigates

As it turns out, the two women indeed had an accident, destroying Allan Glore's T-Bird when it jumped a curb and rammed into some bushes in front of the Village Inn Motel, 3012 South Congress. The cops arrived and one witness told them he saw the car crash into the bushes. According to affidavits signed by APD Officer M. Forshee, who was at the scene, Glore was "stumbling and staggering." Glore was "fighting and crying," Forshee noted, and her clothing was "disorderly and soiled." None of the standard drunk driving tests were administered, Forshee noted, because Glore "was so intoxicated that I feared for her safety. Subject was so unsteady on her feet that she needed support." Nor was Glore the subject of any Drug Recognition Expert evaluation -- undoubtedly because the APD does not have any specially trained Drug Recognition Experts.

Charlotte Hughes remembers the cops arriving -- and she remembers trying to get them to arrest her. She gave them a false name, she said, and "for whatever reason" wanted them to take her to jail as well. But the cops released her and she left the scene.

According to another affidavit filed by Forshee, while he was transporting Glore to the Travis County Jail in his squad car she became "irate and upset over the whole ordeal." "Ms. Glore began banging her head and feet against the rear windows to get attention," Forshee wrote. "As Officer Forshee was pulling the vehicle off to the side of the roadway, the suspect kicked out the window with her feet. A rear passenger window was completely shattered out."

Glore was charged with criminal mischief for destruction of city property, but she says she doesn't remember any of this. It wasn't until the next day, when Hughes retrieved Glore from the jail, that the women say they began to put the pieces together. "We haven't talked about it too much, except for that first day, because we didn't want to be accused of trying to get our stories straight," Glore said. "But we did try to put it together to see what each of us remembered so we could try to figure out what happened." Before going to the hospital, Glore wanted to go home. "I was desperate to see [my kids], and they were freaked out," she said. "Nothing like this had ever happened."

At home Glore stripped off her clothes and placed them in a plastic HEB sack and took a light shower. She headed to the South Austin Hospital, where she requested both the rape kit and the toxicological screen. APD officer Christopher Hallas, who took her report, informed Glore and the hospital staff that they would not authorize the tests -- because they did not believe Glore's story. "The APD officers called in on their radios and then they said, 'we don't believe you were raped, your timeline is wrong, there wouldn't have been enough time for you to be raped,'" she said. "I was stunned, I was shocked. It was all emotions. I was grieved. I've never felt so let down and so lost."

Curiously, although the officers refused Glore the rape kit -- which would have been administered by specially trained nurses at St. David's hospital for the sole purpose of collecting physical evidence that can be used in court -- they did take the clothes she had brought in the plastic bag. Glore said, "They told me it was for evidence."

By the time Glore arrived home that night, she says, she had pretty much given up hope of getting any help. She took another shower, and when she got out, she said, she saw herself in the full-length mirror for the first time. "I saw claw marks above the fold [of my buttocks]," she said. "And when I [looked further] I saw there were claw marks all coming out from my rectum." Glore again decided to try to get some help. She called a lawyer chosen at random from the phone book and laid out the situation. The lawyer, Glore said, suggested she try to go to Brackenridge Hospital the next day to see if she could get some help. She did so -- and again, when the cops were alerted that she was requesting a rape kit exam, the request was denied. "They told me, 'You've been told we're not going to do it,'" she said, "'and you can't pay for it.'"

Meanwhile, Hughes had also visited the hospital for an examination. Among other injuries, doctors found that she had bruises around her spleen, and a severe concussion.

(Department of Public Safety Offender Database)

When her then-estranged husband Allan got word of Glore's treatment by the police, he was furious. "I called [APD's] Internal Affairs [division]," he said. He told them his wife had been refused the rape exam twice and questioned the department's motives. Had the APD been trying to cover something up? "Their response was that they would investigate, but that if they found nothing, they would charge her with perjury," he said. Finally, Virginia Glore said, APD Sgt. Tim Kresta contacted her and wanted to take a full statement from both her and Hughes, wanted to have a police photographer take pictures of their injuries and wanted to get DNA swabs. Eleven days after the Aug. 4 incident, Glore and Hughes made their statements and were photographed. Their injuries remained visible: the claw marks on Glore's buttocks and anus and the numerous bruises on both women, including a set in the shape of two hand prints on Hughes' inner thighs.

But it wasn't until February of this year, when Glore called Detective Rick Shirley -- who was newly assigned to the case -- that she was told that DNA residue had been found on the clothes that she had given to the police. She was also told that the police had tracked down one of the two men from the Aquarium bar that Hughes had described. Glore was told the two men, Chris Turnock and Stefan Feige, were in fact felons who had escaped from a Houston-area halfway house -- moreover, Feige was a registered sex offender. According to the Texas Dept. of Public Safety's registered sex offender database, Feige was convicted in 1997 on one count of aggravated sexual assault of a child -- his victim a 5-year-old girl. According to Department of Safety spokeswoman Tela Mange, Chris Turnock has an extensive criminal record, including everything from DWI and evading arrest to forgery and grand theft, but no sexual assaults. He is currently serving a state jail sentence of five years for grand theft.

But Detective Shirley told Glore the DNA which police had found on Glore's clothes belonged neither to Turnock nor Feige. "He said one of them was back in prison and that they'd lost one of them [Feige] up in Dallas, but that they would get him," she said. "I just went home and cried."

According to APD Commander McNeill, Feige is still on the lam.

APD: 'Things Happen'

"Everyone who says they were raped, weren't [necessarily] raped," says McNeill. "I know that one comes as a surprise. You know, things happen." Things like not getting home on time, or drinking and flirting, he said, are circumstances that might compel a person to fabricate a rape allegation. And in this case, McNeill insists, the APD investigators did a good job. "I am perplexed by the outcry," he said. "If ever there was a case that was done correct, it was this one." McNeill said he was told that Glore never told the arresting officers that she had been raped. All she claimed, he said, was that, "She didn't feel right down there, indicating her pelvic area." Moreover, McNeill said, when police contacted Hughes the following morning, she told them "nothing happened." "She said, 'We were all together that night and nothing happened.'"

McNeill's version of what happened completely perplexes Hughes, who insists that she never made any such statement, and moreover that she was never contacted by police until some time after Glore's husband Allan raised a stink with Internal Affairs. She said she was not contacted by the police at all Aug. 5, the day immediately following the incident. "They never called," Hughes said. "They never spoke to me, and they never called the house." She reiterated that she had no conversation at all with the police until she and Glore made their official statements Aug. 15 -- 11 days after the incident.

McNeill insists the department handled the situation correctly. In retrospect, he admits that it might have been a good idea to administer the rape exam -- but the reason the officers didn't, he repeated, is that Glore never specifically told the arresting officers that she had been raped -- although he didn't suggest any other reason she might have had for requesting a rape test. McNeill did acknowledge that it is APD policy that if a person thinks they've been assaulted, "We do the rape exam."

"We could do all the 'Could have, would have, should have,'" McNeill said. "If you want to, you could say we dropped the ball, but we didn't do so callously. We did the preliminary investigation." (see "Questions Unanswered," p.22.)

To an outsider, the results of that "preliminary investigation" might be shocking -- but apparently to the police they were unremarkable. Investigators found DNA on Glore's underwear, but they have not yet found a match with a suspect. Based on the description of the two men that Hughes gave police, investigators were able to track down two suspects, Turnock and Feige, who were found to be "absconders from a Houston halfway house," McNeill said. "One [Feige] was a registered sex offender and one [Feige] is still on the lam."

Yet, astoundingly, McNeill said the two men were cleared by investigators after Turnock -- who had turned himself in to Houston police -- told the police nothing had happened that evening. "He gave a full statement to detectives," McNeill said. "He said he never saw the other guy [Feige] have sex, though he did see him [with Glore] in the back of the car, petting heavily." Furthermore, McNeill added, investigators took the felon's word that there was no one else with them that evening -- possibly the person who could've been the source of the DNA found on Glore's clothes. Apparently, that was enough for the APD to conclude that the men did nothing wrong.

Besides, McNeill said, investigators had turned up enough evidence to confirm to their satisfaction that Glore was intoxicated when she was arrested, and in this case that seems to have taken precedence. "Now they are trying to say she was drugged up, but we have evidence to the contrary," he said. "[We have evidence] that she was blitzed, based on the drinks she did have." When pressed, though, McNeill admits the department has no way of knowing whether or not Glore and Hughes were drugged, in addition to what they openly admitted to police they had had to drink. "I'm not saying," McNeill acknowledged, "she couldn't have been drugged."

Whatever McNeill's speculations about the possibilities, the APD's rape "investigation" has definitely taken a back seat to what the police and the prosecutors consider a more pressing matter: prosecuting Glore for the DWI charge, currently anticipating a jury trial in the court of County Judge David Crain. The prosecuting attorney of record, Gilbert Barrera of the Travis Co. District Attorney's office, declined to comment for this story. But his supervisor, Travis Co. Attorney Ken Oden, said while his office has no jurisdiction over the rape case -- rape is a felony handled by District Attorney Ronnie Earle's office -- he does have jurisdiction over the misdemeanor DWI charge.

Oden insists that evidence presented to his office by APD indicates Glore was intoxicated. "She is raising the question of whether or not it was voluntary intoxication, which would be a defense if it can be proven in court," said Oden. "I don't know what kind of proof would be brought forward. ... But our job is to evaluate that evidence and our position is to look at each piece of evidence we can." Oden said he tends to believe that Glore is fabricating the claim that she was drugged and raped. Why does he think so? "So far, the police say those claims are not credible," he said. "What you're saying is what [Glore] would like you to say."

To Glore, none of this official reaction comes as a surprise, even though it still hurts. "That's what they've been saying all along, that I made all this up," she said. "I could maybe understand their story if I had a string of DWIs or something. [But] if I had just gotten stupid and gotten behind the wheel of the car and crashed it, then I would take the responsibility for it." Glore has no criminal record, and she still has no idea why she was driving that night, except, she said, for another lingering and uncertain impression -- "that we were trying to get away. I have a feeling of desperation when I think about it," she said. "That's all I can figure out. We were trying to get away. But nobody believes us."

Nobody, that is, within the APD or the County Attorney's office.

The Rapist 'Drug of Choice'

"Somebody needs to get their head out of that dark smelly place over there at the Austin PD and get going on this stuff," says Jim Mock, a retired police officer from the Torrance, Calif., Police Department who currently teaches drug recognition classes to law enforcement agencies across the country. For Mock, Glore's story, when dissected and understood, is a clear example of drug-facilitated rape. "The fact that [the police] didn't believe the girls and did believe those guys is amazing. And I don't have any tolerance for that kind of attitude."

Mock identified two drugs currently on the street that are increasingly linked to rape and sexual assault cases. Rohypnol is the better known. Commonly referred to as "Ruffies" or "Forget-Me Pills," Rohypnol is a central nervous system depressant 10 times stronger than Valium, and generally renders a victim unconscious for as long as 12 hours. "With Rohypnol you generally don't stay awake," Mock said. But another drug, GHB (also a CNS depressant, commonly available in liquid form) is increasingly becoming what Mock calls "the sex offender's drug of choice."

"With GHB, you can stay awake, but you do not remember," Mock said. "It has basically infiltrated the bar scene and the club scene. It is easy to slip into a drink, and it has almost no taste. It is very dangerous."

The full name of GHB is Gamma Hydroxybutyrate -- it also carries a street name: "Easy Lay." GHB was banned by the Federal Drug Administration in 1990. According to Federal Drug Enforcement Administration intelligence reports, GHB was originally thought to help stimulate Human Growth Hormone (later studies established that it does not). Initially it became popular with weight lifters and was commonly sold in health food stores from the mid- to late Eighties.

The 1990 FDA ban has apparently done little to curb GHB use. The drug can be manufactured at home, with very little knowledge of chemistry, using chemicals readily purchased over the Internet. The ease of manufacture has helped make GHB so dangerous. "This stuff is toxic," said Tracy Bahm, an attorney with the American Prosecutors Research Institute and head of the institute's Violence Against Women unit. When mixed at home without properly monitoring the levels of various chemicals, she said, GHB can be deadly. According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network, an arm of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the number of GHB mentions in emergency room admissions across the country has skyrocketed. In 1994, GHB accounted for less than 100 mentions, ballooning to over 1,200 mentions by 1998. By January 2000, the DEA had documented 60 GHB-related deaths. According to the Centers for Disease Control, GHB is a solvent commonly found in super glue removers and industrial strength cleaners. "And when they are slipped into a drink," said Bahm, "the person just appears very drunk."

The fact that police at the scene of Glore's wreck assumed that she was simply intoxicated does not surprise Mock, especially considering there were no trained police drug experts available to assess the situation. (There are currently no drug intoxication experts on the APD staff.) Furthermore, Mock said, other elements of Glore and Hughes' account of events describe all the hallmarks of GHB ingestion. Hughes' recollection of throwing up while riding in the car ("It's almost guaranteed that you'll get sick," he said, "it's one of the tell-tale signs"), and Glore's combative attitude, including kicking out the squad car window ("It can get very violent," Mock said), are typical elements of a GHB drugging. And the sequence of events inside the Aquarium, where Glore and Hughes met the two halfway-house escapees, Mock described also as fairly common.

"The sex offenders know about GHB. It is common knowledge with those people," Mock said. "What you have described to me is the exact M.O. I've seen with GHB over and over again." Moreover, he added, the suspects in such cases are typically strangers. "The big thing is that usually people that are the suspects are ... usually people that [the victims] meet in bars," he said. "In California, 90% of this is actually done by the bartenders." To further complicate such cases, Bahm said, is the fact that to an outside observer the offender oftentimes appears to be helping the victim. "[A drug is] slipped into a drink and the person just appears very drunk," she said. "And oftentimes a person who comes to that person's aid looks like a rescuer when, in fact, often they are the rapist."

Professional knowledge of the use of GHB, said Mock and Bahm, is only half the battle. Rohypnol and GHB are both extremely difficult to detect in a standard toxicological screening, because the body usually processes them within eight hours. And since it only takes a very small amount to render a victim powerless -- with GHB it can take less than a water-bottle capful to send a victim into a waking coma -- testing becomes even more difficult. "A lot of labs are not even equipped to test for these drugs," Bahm said. "It only takes a small amount, so you have to test for these miniscule amounts, and if you aren't doing that, you'll miss it."

The very biggest problems, the experts said, are the overall underreporting of drug-facilitated rapes, and the ignorance of law enforcement agencies on how to spot and investigate such cases. According to APD statistics, 353 rapes and 845 sexual assaults were reported to police last year. But according to Autumn Williams, a spokeswoman for SafePlace, Austin's shelter for rape and abuse victims, statewide statistics show that nearly 330,000 people reported to rape counselors, medical professionals, and police combined that they were a victim of rape or sexual assault that same year. To compound the official ignorance, neither the APD nor the state have any indication of how many of the reported cases may have been drug-facilitated -- because they do not statistically distinguish those cases. "We haven't, over the years, collected that as a separate category," McNeill said. "What we maybe need to do is start looking at that."

According to Mock, Bahm, and Williams, accurate reporting of sex crimes is the only way to determine the scope of the problem. Yet at least one former SafePlace employee said she understands why victims don't always go to police. "I have seen [police] be just brutal when questioning a victim," she said. "And sometimes this is a victim who has just been assaulted. They have blood and cuts, and they are traumatized, and the cops are just brutalizing them and asking them what they did to cause this to happen." When a victim has admitted they ingested alcohol, the source said, it is even worse. "If you say you'd been drinking, even if it is only one beer, forget about it," she said. "If there was any alcohol involved at all, [the police] assume the victim is completely culpable."

McNeill insists the APD is "diligent" about protecting rape and sexual assault victims. The last thing the department wants, he said, is for them to feel as though they were raped twice. "This department bends over backward to make sure we have the victims covered," he said. "All I can say is that we work very diligently to keep up and make sure the person is not victimized again."

McNeill's assurances do not appear to have been of much influence in the APD investigation of what happened to Charlotte Hughes and Virginia Glore. Does McNeill think Hughes and Glore have been "covered"? "If we want to take this one case and dissect it, we could do that. And, looking back, we could've done a rape kit exam," he said. "But [the investigating officers] felt there just wasn't anything to substantiate her being sexually assaulted."

The Road Back to Normal

Now, a little more than a year later, Glore says she feels that her life is finally getting back to normal. "I am finally starting to feel like Jenny again," she said. "And that is great." It's been a hard year for both Hughes and Glore. In the wake of the assault and the police response, early this year Hughes decided to leave Austin and move home to be with her family in Winnie. "[After a while] it was just like [the investigation of the rape] just disappeared," Hughes said. "I left town because I just couldn't take it any more. I needed my family; I'd had enough."

Hughes travels back to Austin each time Glore must be in court for hearings on the DWI charge, and she intends to be in court when the case finally goes to trial. Hughes says she is determined to let people know what actually happened that night, even if the police don't care. "Everything we've said they've just sloughed off and have ignored," she said.

Glore is also determined. All she wants out of this experience, she says, is to try and educate other women -- and, perhaps the police and Legislature, if possible. "I want to increase awareness and then maybe [the APD will] get a training program within the department to be able to tell when someone has been drugged," she said. "I'm gonna raise hell if I can. We've got to get a law passed [to mandate the administration of rape kit tests]. What the police think cannot be the be all and end all in a case like this." n

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.