Naked City

Broken Down -- Or Just Plain Broke?

By Kevin Fullerton, Fri., July 6, 2001

How much would state lawmakers be willing to pay to preserve equity in the Texas public school system if the courts were to prohibit them from setting limits on how much wealthy school districts could spend? Would they spend state dollars to keep a rural outpost like Muleshoe on par with a rich suburb like Coppell, or would they decide that the less fortunate are doing fine with what they have? Advocates for poorer school districts would rather not find out, and that's why they're siding with the state in trying to win dismissal of a lawsuit filed by wealthy school districts that would strike down the state law that caps districts' property tax rates. Joined by the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF), representatives from poorer districts argued alongside state lawyers in Travis County court Thursday that the tax cap, which prohibits Texas school districts from raising their tax rates above $1.50 per $100 assessed property value, is a necessary defense against inequitable school funding. Most observers expect this case to eventually appear before the Texas Supreme Court if Judge Scott McCown rules that the lawsuit can proceed.

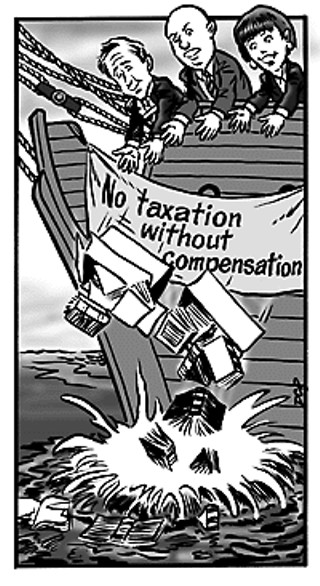

Lawyers for the school districts pressing the suit, organized as the Texas School Coalition, argue that the time has come for the state to re-examine the school financing system it set up a decade ago after the Texas Supreme Court ruled that the state had failed to provide equal education to all students. They argue that the solution created by the Legislature -- to both limit the amount school districts can raise and redistribute money from rich districts to poorer ones (known as the "Robin Hood" plan) -- was never meant to be a permanent fix. Now that one in five districts has reached the cap, and wealthier districts have started to suffer budget shortfalls as they try to maintain programs while paying out hundreds of millions in tax receipts to poorer districts each year, the Coalition argues that the tax cap is unconstitutional. Since many districts are forced to place their tax rates at $1.50, the cap is effectively a statewide ad valorem tax prohibited by the state's constitution, say Coalition lawyers.

But representatives from poorer districts say the lawsuit is really a disguised effort by rich districts to avoid having to share their wealth with the less fortunate.

"Regardless what the plaintiffs argue, the great majority of them would like to see the Robin Hood system go away," says Craig Foster, spokesman for the Equity Center, a nonprofit that represents less affluent school districts in Texas. The era before Robin Hood was established, says Foster, was "the good old days" for districts that drew off wealthy property bases. "You could spend twice as much for half the tax rate [as poorer districts]," says Foster. "That was wonderful [for them]."

George Bramblett, the lawyer representing the Coalition, responds that the lawsuit has nothing to do with knocking over the share-the-wealth component of the current system. He says if the suit is successful, it will force the state to spend more dollars on education for all districts, rather than trying to maintain parity by capping the spending of the richest ones. "There's not enough money in the system," says Bramblett. "If you add more money to that system, it will alleviate over-reliance on property taxes." A decade ago, the state funded about 60% of the cost of public education through its general fund; this month, a report showed that the state's share has fallen to 40%, placing a heavier burden on local property taxes.

But opponents of this lawsuit argue that the current system, however flawed, has made significant strides toward equalizing education opportunity in Texas, and they don't care to see one of its central pillars kicked out. MALDEF's Al Kauffman says that even though he agrees with Coalition schools that the state should kick in more for education, most school districts are meeting basic standards while staying under the $1.50 cap, thus undermining the basis for their lawsuit.

Foster and others remember how the Legislature handled the Edgewood case back in 1987, when the South Texas district sued the state over its inequitable school-finance system and triggered the reforms that resulted in Robin Hood. Foster says the Legislature came up with the $1.50 cap based on lawmakers' contention that the level of public education in Texas at the time was good enough. If the Supreme Court were to remove that cap now, he says, the Lege would again be forced to decide what constitutes an "adequate" level of funding for schools, because Robin Hood assumes a cutoff point above which districts must give tax revenue back to the state.

Foster says his experience teaches that the Legislature would likely set that level at a point most districts have already attained, clearing the way for wealthier districts to claim that poorer districts don't need as much of their money. "It's the easy way to settle the problem," says Foster. "Anybody familiar with the Edgewood litigation understands that that is a possible outcome."

Educational consultant Dan Casey notes that even if the state committed to greater equalization of funding in a tax cap-free system, it lacks a funding reservoir capable of pumping in the billions that would be needed. Then there's the question of whether local districts want to be dependent upon the state to begin with, Casey adds. "I don't think anybody has a very conclusive idea right now of how you'd proceed [if the lawsuit succeeds]" says Casey.

The Austin Independent School District, which attained Chapter 41, or "property rich," status in 1999 and has since faced annual budgetary crises (AISD will have to hand over $100 million in revenues next year), says it has no plans to join the lawsuit, even though it is a prominent member of the Texas School Coalition. The district says it prefers to let the Legislature craft reforms to the present school finance system -- free from court-ordered mandates -- in the 2003 session.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.