The Death and Life of Free Radio

Austin Microradio Lived Fast and Died Young. Will the Movement Live to Broadcast Another Day?

By Emily Pyle, Fri., June 22, 2001

We're listening to the sound of a man kicking in a door.

Everyone in the room but me has heard the tape many times. I've heard it only once before. Still, when it comes to the part where the man starts to kick down the door, we all lean in, we stop talking.

"I'm perfectly willing to let you in." The recorded voice of Free Radio Austin's last broadcaster. "Just show me your search warrant. Can't I just see your search warrant?"

More banging and the sound of wood starting to splinter -- then under that, very faint, a man's voice: "If you don't let us in the door we'll come through the wall."

Somebody in the room speaks up, over the tape. "This is where they go around to the window." The sound of glass breaking.

The first time everyone else here heard this, it was broadcasting live: the last five minutes of Free Radio Austin.

Radio broadcasting works like this: You speak into the microphone, and the sound of your voice moves the air ahead of it in waves. The waves disrupt the current in the microphone as it flows into the transmitter. The transmitter converts the disrupted current into a radio signal that the antenna sends into the air. Signals move in ground waves and sky waves. Sky waves vanish upward. Ground waves move straight out. They can be received only to the point where the earth curves away beneath them; after that, like Wile E. Coyote running off the edge of a cliff, the signals continue straight while the ground drops away underneath them, and all the Soft Rocks and Hot Countries and Top Forties whistle off into space and disappear forever.

Some time before the signals leave the earth, however, they become the property of the U.S. government. Between the time the sound leaves the broadcaster's throat and the time it reaches your ear, it comes under the regulation of the Federal Communications Commission, that dry, low-profile governmental body answerable only to Congress, best known for overseeing the mergers of communications giants like Time Warner and Viacom. The FCC is the only governmental body that can grant an official radio station license to broadcast. They never granted one to Free Radio Austin, which is how it happens that the door is being kicked down.

In 1978, the FCC stopped issuing licenses to stations that operate at less than 100 watts. With small stations banned from broadcasting, access to the airwaves was granted more and more to those that could afford to run a high-watt station: that is, to commercial stations whose advertisers could finance the state-of-the-art equipment and professional broadcasters it takes to run a station at 1,000 watts -- or 10,000 or 50,000. Yet while commercial radio interests like Clear Channel Communications grew and prospered and took up more and more of the airwaves during the past two decades (Clear Channel now owns more than 900 stations across the country), hundreds of technically illegal low-watt stations mushroomed quietly around the country. In cities, they operated under the shrill blare of the big, expensive stations, working without advertising dollars, broadcasting what the volunteer broadcasters themselves wanted to hear. In rural areas, they put local news on the air to audiences so small, no commercial enterprise could make a profit on them.

The rebel stations' argument was straightforward: The airwaves, said advocates of what was becoming the "microradio movement," are a natural resource, like water, and control of that resource belongs to all the people, not to commercial corporations. Needing advertising money to survive, commercial stations are constrained to serve the interests of advertisers, not the interests of the listeners -- and the microradio stations would fill the gap.

Last summer, Central Texas had three microradio stations: Free Radio Austin and Radio One in Austin, and KIND Radio in San Marcos all broadcast without the benefit of licensure. Now there are none. Order has been restored to the airwaves. Hoping to stave off jail sentences or fines from the FCC, three Free Radio activists signed an agreement early in May that saddles them all with permanent injunctions against any future radio broadcasts. Radio One, Austin's other, younger, micro station, also busted last fall, has gone digital. Now streaming over the Internet ( www.radio1austin.com), Radio One is altogether legal, but has lost the sector of its audience that won't or can't afford to follow them onto the Net, a different sort of medium altogether. If microradio has any future here -- or anywhere else in the country -- it may rest with KIND Radio in San Marcos, a micro station whose case, for now, has been suspended by a sympathetic federal judge.

Some Must Be Denied

In the early days of microradio, the FCC was at a loss on how to deal with rogue stations. Clearly, the stations were unlicensed, which made them illegal. However, microradio supporters pointed out that at less than 100 watts there was no license the stations could have applied for, which left them in a legal limbo. A bewildered FCC levied massive fines on the stations, but rarely attempted to collect. With the backing of the courts, the FCC resisted making First Amendment cases out of microradio shutdowns, by relying on two entirely dry and technical arguments against microradio.

The first is interference. Broadcast equipment not tested and certified by the FCC and not operated by professionals, the FCC says, may not make clean transmissions. Radio signals may bleed over onto nearby frequencies, interrupting the broadcast of other stations or disturbing ambulance signals, police broadcasts, and air traffic control transmissions.

Secondly, the radio bandwidth is only so wide. Since a finite number of the waves travelling through space will carry a radio signal, there are fewer frequencies than there are would-be broadcasters. Historically, the Supreme Court has upheld the limited bandwidth argument to the tune that "because it cannot be used by all, some who wish to use it must be denied."

Yet those with the money to own and operate a 10,000- or 50,000-watt station rarely fall in the category of those who must be denied. And in recent years, the rich have gotten much richer. Ever since the passage of the Communications Act of 1934, the limit on the number of stations a company can own within a single listening area -- once severely limited -- has risen steadily. The 1996 Telecommunications Act lifted limits on the number of radio and TV stations a single company can own, and allowed ownership of multiple radio stations within a single city.

Free Radio Austin, like most micro stations, doesn't dispute either of the FCC arguments directly. They just don't feel that the arguments are sufficient to shut them down. "We realize that a regulatory body needs to be there," Reckless, a former broadcaster at Radio Free Santa Cruz and backbone and a founder of Free Radio Austin, told Judge Sam Sparks of the Western District court at Free Radio's hearing last November 13. "It is a finite spectrum, and we just feel that we deserve some of it."

As for interference -- never mind that a 100-watt station interferes with a 50,000-watt station like a jackrabbit interferes with an 18-wheeler -- most micro stations say they are scrupulous about keeping their transmitters tuned and using filters and compressor limiters, all of which are supposed to reduce interference. At the hearing, an FCC agent admitted that Free Radio's equipment had never been bench tested by the agency to see whether it could have caused interference. And only one complaint had ever been lodged against Free Radio Austin -- by Austin residents who claimed it interfered with their reception of KGEL 97.1 in Fort Worth.

When microradio cases do make it into the courtroom, judges tend to shut the stations down without flourish. When broadcasters and supporters have tried to bring free speech issues into the cases, judges have shrugged. However the law ought to be written, broadcasters were clearly in violation of it the way it is written now. To change the law would require a lengthy round of appeals for which few microradio operators have the time, the money, or the lawyers.

In 1991, Stephen Dunifer of Free Radio Berkeley was the first broadcaster to get a judge to listen to a First Amendment argument. Twice, federal judge Claudia Wilkens refused to shut Free Radio Berkeley down or issue a permanent injunction against Dunifer, while she directed the FCC to reply to his claim that his free speech rights were being violated. Finally, the FCC presented Wilkens with a technicality: Dunifer had never applied for a license (although his station ran at less than 100 watts and would undoubtedly have been refused) so he couldn't claim to have exhausted legal recourse. In 1994, Wilkens bought that argument, and permanently enjoined Dunifer from broadcasting. (His Web site still sells cheap kits for building transmitters and other broadcast equipment "for education purposes only." Unconfirmed rumor has it that the Zapatistas use Dunifer's kits to broadcast in the mountains of Chiapas.)

After Dunifer was shut down like many micro stations, Free Radio Austin took the hint. The broadcasters sent a letter to the FCC in February of 1999, requesting a waiver of licensing requirements. They received no answer. In April, they went on the air.

The station broadcast at only about 70 watts, enough to be heard reliably around central East Austin -- on a good day, some say, as far away as Bastrop. A lot of the programming was music, and a lot of it was political commentary. Some of it was cranks ranting late at night, or awkward poetry readings. The music tended toward the obscure and the politics toward the radical, but ultimately what broadcast at the 97.1 MHz frequency was up to Free Radio's 100 or so programmers -- cab drivers and waiters, Vietnam veterans and teenagers.

"It was in the hands of the broadcasters," says Reckless. "There were some unwritten rules, like if you were going to talk about something really controversial you had to let people call in, you couldn't hang up the phones. But we didn't tell people what to say. People would ask us, 'Well, if a bunch of Nazis wanted to be on Free Radio, would you let them?' And our answer was yes. Free speech means you also advocate the rights of the people with whom you disagree."

Calling Agent Perry

Free Radio got their first visit from the FCC in June of 1999. Agent Loyd Perry came to the door of the East Austin home where the station was housed. Perry identified himself, informed the broadcaster on the air at the time that the station was in violation of federal regulations. He asked for the station's transmitter. The broadcaster, young and scared, handed it over. End of round one.

By the end of the summer, Free Radio was back on the air in a new location, and by the following February, the FCC knew it. A "secret broadcast" is something of a contradiction in terms, and Free Radio Austin was never very good at keeping a low profile. Around town they were an open secret; their stickers were on the bathroom walls, supporters wore Free Radio Austin T-shirts in the street. Perry read about them in the Chronicle and looked them up on Web sites devoted to "pirate" radio stations.

Throughout the spring and summer, the FCC sent out warning letters by certified mail, which station operators refused to sign for. Three times in March and once in August, (according to his deposition for a seizure warrant), Perry drove to Austin from the FCC's Houston enforcement office and spent the day tracking the errant radio signal. He used a van equipped with an electronic tracking device, but his backup method worked just as well: in the phone book, he cross-checked the refusal signature on the returned letters with the phone number the station gave out as its call-in number. 2939 East 14th Street. On October 10, just a few days before the Fortune 500 conference blew into town, Free Radio was busted. The FCC showed up at the station, this time with several agents and accompanied by APD officers and federal marshals. A broadcaster put out a call to all listeners to come and defend their station. A crowd of 40 or 50 showed up to watch a private construction crew dismantle the broadcasting tower, but there was not much anyone could do. It was all over pretty fast.

Seventy-two hours later, from the garden shed of another East Austin home, Free Radio Austin was back on the air. The final bust came less than a month later, on November 6.

"We were expecting something to happen, obviously," says Til Chamkis, who was broadcasting at the time of the November bust. "We were on guard, but there had been a pretty good rain and the studio had gotten wet inside, so we had the doors open to air it out. I wasn't that long into my show, and up the driveway comes a horde of Austin police, FCC, a federal marshal, so I closed the doors and they proceeded to go through the motions of kicking them in.

"I kept asking them to show me their search warrant; that was all I was asking for. Eventually they went around and broke a window, and that's when I opened the door -- and then they shut us down."

In truth, Free Radio was not really trying very hard not to be shut down. To some of the programmers, their hour or two on the air each week may have been the only point, but to the organizers, the shutdown was a move in a larger game. This was "illegal direct action": civil disobedience, after a fashion, aimed at the FCC, at the government that tenures them, and at Big Media and the corporations that own it. If your direct action doesn't make anyone angry enough to retaliate, to take you to court where you have a shot at changing the law, then it hasn't counted. So they got shut down. It was part of the deal.

Within a week, the FCC filed suit against Free Radio Austin -- or rather, as the brief reads, the United States of America filed suit against Reckless, Chamkis, and John Seibold -- the three people they could firmly associate with the operation of the station. Chamkis they caught on the air. Seibold's name was on the lease of the property that housed Free Radio's third and final studio. And Reckless -- well, she was implicated four or five times over. The suit also names as defendants "any and all John and Mary Does found operating an unlicensed station on 97.1 MHz."

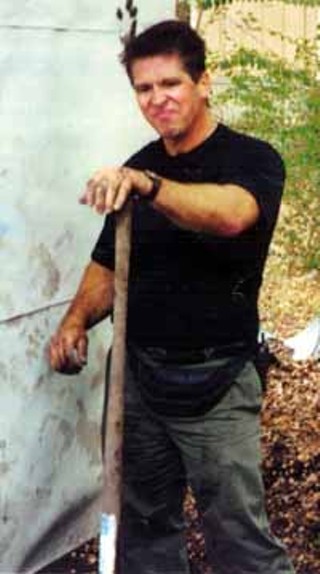

From the back steps, Reckless points out a concrete slab about 2 feet by 2 feet. The empty rusted housing in the center used to anchor the radio tower. The hole the FCC dug to find the transmitter is full of rainwater. This, the site of the second bust, is also her house. "Microradio is a vital first step in having any type of solidarity in the community," she says. "We live in a time when people don't know who their neighbors are, don't really know what the issues are.

Photo courtesy Free Radio Austin

"The whole sound bite thing that commercial media does -- it really does reduce your critical thinking skills. What's going on in Iraq, for instance -- there's no way you can understand that in 15 minutes. That's a three-hour discussion. Nobody on TV or radio has three-hour discussions except for microradio stations and community radio stations that care about these things -- that will go so far as to break the law to get these things on the air."

She sighs with impatience. "It's not a big deal, it's really not. We just want to talk to each other."

Critical Thinking

The hearing on November 13 was short. While the FCC presented no positive proof that other local radio stations had experienced interference from Free Radio Austin's transmission, and while Sparks said broadcasters had "the best of intentions at heart," there was no doubt that they had been on the air without a license. The letter of the law was unquestionably broken. Responding to the FCC's claims of urgency and "irreparable harm," Sparks granted temporary injunctions against Reckless, Seibold, and Chamkis. A court date was tentatively set for the following spring and the three started looking for a lawyer.

On February 5, their day in court was abruptly curtailed. The FCC asked for and received a summary judgement -- the kind of judgment you get when you contest your traffic ticket but skip your court date. It turned out no one from the station had filed a claim to the court against the broadcast equipment seized in the first bust. After 10 days, the seizure became final and the equipment was forfeited. Tacked onto the end of the forfeiture papers -- seemingly as an afterthought -- was a permanent injunction against the three defendants.

Within the statute of limitations, a summary judgment is fairly easy to overturn, but still without a lawyer, and with their confidence on the wane, Chamkis, Seibold, and Reckless sent a letter to the FCC in May. The letter announced their intention to accept the permanent injunctions and asked the FCC to drop further legal proceedings. Early in June, the FCC agreed.

"I know everybody gets shut down," Reckless says, "And what I really wanted to do was fight the case and win -- at least for our district -- the right to communicate. But I don't think any of us knew how much time and money and support you need to fight a federal case like this."

Besides time and money, there was the concern that the names of other Free Radio programmers would be dragged out during a trial. With its dangling "John and Mary Doe" clause, the case was conveniently ready to swallow any additional broadcasters or operators the FCC could identify. At the hearing, U.S. Assistant District Attorney Britannia Hobbs asked Reckless to provide names and numbers of other broadcasters. When Reckless said she knew most of them by first names only, Hobbs asked her to turn and point them out in the crowd of supporters packing the courtroom. Reckless refused, as did Seibold. Sparks upheld the refusal for the purposes of the hearing, but pointed out that such a refusal during a trial would amount to contempt of court.

"There was no way any of us was going to narc," Seibold says. But scrapping the court case to protect programmers' names went beyond a sense of honor among thieves. If any of those programmers have a shot at returning to the air, it now depends on their names staying secret.

While Free Radio Austin was jousting with the enforcement bureau of the FCC, the agency's administrative offices were in a huddle with Congress, engaged in rule-making that would permit the licensure of Low Power FM (LPFM) stations -- low-wattage stations operated by nonprofit groups. While microradio advocates have several bones to pick with the LPFM licenses, at the moment they are the last, best hope for microradio operators who want to return to the air. There is one big stumbling block: LPFM licensing requirements automatically bar anyone who has participated in the operation of an unlicensed station. Any Free Radio programmer whose name came out in court would be out of the running immediately.

Keeping San Marcos KIND

Free Radio Austin's courtroom rout is the rule for microradio stations. The exception is just 70 miles down the road in San Marcos, home of KIND Radio. At this time, KIND has the best legal standing of any microradio station in the country. KIND is suing the FCC.

"What we're saying in our lawsuit is that the FCC has become subservient to the corporate interests, to the detriment of the private citizens it was established to protect," says broadcaster and KIND co-founder Joe Ptak. "Corporate interests, commercial interests, are not the same as private interests."

For KIND, media coverage in and of San Marcos is a prime example. The city is squeezed between the two huge television and radio markets of Austin and San Antonio, and San Marcos news is all but ignored by the local media, whose advertisers pressure them to attract the big markets to the east and west with coverage of Austin and San Antonio.

Photo courtesy Free Radio Austin

In March of 1999, Ptak and co-founder Zeal Stefanoff wrote to the FCC, explaining their intent to start a radio station in San Marcos and requesting a waiver from "any regulation they thought might apply." They sent along a $25 check to cover any filing fees. Ptak and Stefanoff are not green to the snarls of media law. As operators of the intermittent newsweekly the Hays County Guardian, they had already won one Supreme Court case that allowed them to distribute their newspaper freely on the campus of Southwest Texas State University.

The FCC sent the check back uncashed, and KIND Radio began its broadcast later that month. In due time, they too received a visit from Agent Perry. But "illegal direct action" -- the shutdowns and crowds of protesting supporters, were not KIND Radio's style. They told Perry that they had what they believed was a "bureaucratic dispute" with the FCC. They promised to be in touch. Perry went away.

Throughout the summer, while Free Radio Austin was dodging the FCC's certified letters, KIND was badgering the commission for advice on how to proceed, how to run the station exactly as it was -- except legally. At length, the FCC scheduled an administrative hearing with KIND in Washington, D.C. Ptak requested a change of venue (no time or money to travel to Washington) and an extension -- their lawyer, the one who had seen them through their Supreme Court case, had just died. The FCC denied both requests. Ptak wrote again: If he came to Washington, with no money and no lawyer, would the FCC let him sleep on the floor of agency's office?

The FCC responded with a cease-and-desist order, and an $11,000 fine against the station (both posted on the agency's Web site). The order was not delivered by hand, however, until after the deadline to appeal the order had passed. KIND protested the decision, and the FCC nominally re-opened the case. Shortly afterward, with no further contact by the FCC to KIND, a second cease-and-desist order was posted. This time, KIND sued.

"If we were a multinational corporation, and came across a bureaucratic dispute like this, they would have had us meeting with the FCC, they would have dropped the prosecution and negotiated a settlement with us," Ptak says. "What they did is, they excluded the private citizens' interest -- and so part of our argument is that the FCC has turned the radio spectrum into a license to mint money for the corporate interest."

Either KIND Radio was lucky in the draw for their judge, or else their argument and repeated attempts to settle amicably with the FCC were persuasive. Federal Judge Fred Biery compared KIND Radio to Thomas Paine and Nelson Mandela, and upheld KIND's right to be considered for an LPFM license "on a level playing field" with other applicants. Although there was no way around the fact that KIND had operated without a license, Biery put the case in abeyance until Texas' LPFM application filing window closes in late June. With the legal decision postponed, KIND won't have to check the box on the LPFM application that says they have been legally found to have operated without a license. If KIND's application has not been accepted when the case is taken up again, Biery told lawyers for the FCC, he would expect an explanation.

If KIND's application is accepted, they'll resume the broadcasts they voluntarily suspended last fall. If it isn't, they plan to sue again.

"Either way, we'll get back on the air," Ptak says. "Hopefully, we might set some kind of favorable precedent. At the moment, I think we are the best and brightest hope for microradio stations of our kind."

The Next Thing

Around Austin, if you are in the right place and listening to the right people, you still run across former listeners and old programmers still awaiting Free Radio Austin's imminent return -- if not next week, then maybe the week after that. If you tell them it's not coming soon, if ever, they're incredulous.

At the former home of Free Radio itself, the sun is shining, but the back yard is a sea of mud. One of the blank, towering warehouses that dot East Austin rises over the yard, with its back turned squarely to us. On the steps, Reckless sits smoking.

"To win a war, you need to be able to shoot, move, and communicate," she says. "Even if you can't shoot or move, if you can communicate, you can still win, and so they want that totally crushed. A lot of people think I'm way radical for seeing it in this way, but we're not the ones who started this war. It's unfortunate, but I really do believe that they look at it that way."

"When a government goes to take over another country, the first thing they take over is the airwaves, because that's how you control the public mind. Now the corporations in this country have taken over the airwaves. How impossibly dangerous could that be in a quote-unquote 'free society'?"

She stubs her cigarette out against the steps.

"We do this direct action -- radio -- because it is nonviolent. We know that the government knows how to deal with violence -- that's what they do. That's what they put their unlimited resources into. But, all right, we tried to be nonviolent -- what is the next thing if this doesn't work?" ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.