The People vs. Mike Sheffield

Did Austin's Most Powerful Cop Violate Your Right to Oversight?

By Mike Clark-Madison, Fri., March 30, 2001

You might not feel any different this morning, but Mike Sheffield is happy that the Austin Police Department will now be monitored by citizens like yourselves. It remains to be seen whether what satisfies Austin's most powerful cop will be enough to make you and your neighbors satisfied with the APD.

On March 8, after hearing from dozens upon dozens of aggrieved citizens, the City Council fretfully approved a new three-year contract -- oops, make that "Meet and Confer Agreement" -- with the Austin Police Association (APA), of which Sheffield is president. This agreement institutes Austin's first-ever civilian review of alleged police misconduct, to take effect come the new fiscal year in October -- but in a form that some advocates think is worse than no oversight at all. Those advocates -- notably the Sunshine Project for Police Accountability, the local chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, and other (often overlapping) activist groups -- have been quick to blame Sheffield. The APA president, as a key member of the council-appointed Police Oversight Focus Group, helped craft the proposal under which the city manager would appoint an ombudsman (the Police Monitor) and a citizen review board (the Police Review Panel). After a 7-0 endorsement by the City Council, this proposal was sent on to Meet and Confer, the Texas civil-service lingo for collective bargaining. In that forum, Sheffield then led his APA bargaining team to renegotiate the "management" proposal that he had helped write.

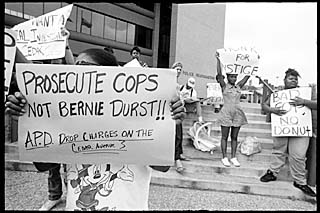

So when Meet and Confer produced a different -- and in the activists' view, gelded -- oversight process, the cops became the bad guys, with weeks of sloganeering like "No pay hike without oversight!" -- that is, the City Council should stick it to the APA and Sheffield by targeting the union's prime plum: a massive pay hike that will move APD officers from the bottom to the top of the Texas pay rankings. As it happens, the APD brass and city administrators -- people who are actually beholden to the council's wishes -- had also signed off on this deal. But perhaps we expect them to put the People's interests in the back seat.

Why do the People want oversight? After a recent history of questionable calls by APD and its officers on professional conduct and the use of force, that may be a question that answers itself. All good-government abstractions aside, this issue has been made hot over the years by the sad or sordid stories of individual people with names, on both sides of the blue wall. More immediately, though, what do the People want oversight to accomplish? Is it primarily a tool for process improvement within the police department, or is it primarily a forum where the bad cops are exposed and their victims' wrongs righted?

The real question behind oversight -- how citizens can and should expect to be treated by the police -- has fermented over the past wild decade, as the police department attempted to retool itself into a force that meets the policing needs of a big city while still responding to historical Austin values. The Police Oversight Focus Group was an effort to force those oft-divergent goals into harmony -- and on the political level, we can safely say, it did not work.

But on a practical level, the oversight struggle has already changed the people who, right now, can change APD. And foremost among them is Mike Sheffield.

Officer Friendly or Occupying Force?

Sheffield is 44 years old, a 22-year veteran of APD, and currently a detective in the narcotics division. But since 1998, he has been president of the APA, which is his real job. (Indeed, the meet-and-confer gives Sheffield the comp time necessary to do the union-boss gig full time.) That means Sheffield is more powerful, when it gets right down to it, than Police Chief Stan Knee. The APA has an effective veto over department policies not to its liking, its political action committee has become a major player in local politics, and APA support has helped more than a few officers get back on the street despite the community and the department's wishes.

He is a big guy, on the near side of six feet but way past 200 pounds, which makes him not-all-that-scary, service weapon notwithstanding: a ruddy-faced sorta-redhead who looks about as puckish as a crewcut, bull-necked, lineman-sized cop can be. In his own view and that of many others, Sheffield is the sort of policeman you'd want Austin to have. (Actually, he lives in Georgetown, where he's also been a thorn in the sides of Williamson County politicos.) Leans left, for a cop. Really smart guy. Reads a lot. Hangs out at downtown coffee shops. Brought women and minorities into the APA leadership for the first time. Held to be a stand-up guy by the prosecutors he's worked with. Solidly behind this community-policing business. "There's still ample room for Officer Friendly," he says. "We're not here as an occupying force, but as people just like you, trying to make things better."

Radicals might balk at the portrait, but Sheffield is a convincing enough Officer Friendly to hack off the Occupying Forces in his own union, which represents all but a dozen of Austin's 1,200-plus police officers and whose previous presidents had been, you might say, a little more macho grande (see "Sheffield, APA, and the Cop Wars," p.34, for a brief history of APA). By comparison, Sheffield has been kinder and gentler from Day One, but especially since he agreed to join the Police Oversight Focus Group, which to some officers was tantamount to sleeping with Saddam Hussein.

Sheffield didn't go to bed eagerly. Back when former Council Member Bill Spelman -- who, in his other life as an LBJ School professor, is a national go-to guy on police administration -- was floating a civilian-review task force, Sheffield and the APA commissioned a poll in which vast majorities of your friends and neighbors gave APD high marks, said they felt safe, and, as Sheffield argued, saw no need for oversight. "Our police got more than three-quarters of a million calls last year [in 1997], and we generated less than 450 complaints against officers,'' said Sheffield at the time. "I see no need for a civilian review board."

But when you hear some of the stories behind those complaints, it's hard to dispute that something ain't working at APD. The Sunshine Project's Ann del Llano -- Sheffield's sparring partner on the Focus Group -- is a criminal defense attorney. In November of 1997, one of her clients, Gregory Steen, lost a kidney after being shot in the back while fleeing a crack house, unarmed, in the driving rain, 60 feet away from the officer who shot him. That is not, safe to say, what they teach you in the academy, but the officer in question got a whopping one-day suspension (which was later waived). Then, despite scant evidence, Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle indicted Steen for aggravated robbery of the crack house. (The charges were later dismissed.)

"I had been volunteering with ACLU of Texas, reviewing complaints as they came in, to some extent, for about 10 years," says del Llano. "So I knew about the complaints and the medieval police process for years. But with Gregory Steen, this was so clearly wrong, and I stepped in as co-counsel to show that there wasn't a shred of evidence for a crime that would send him to prison for 99 years. That case really got my goat; there were so many bad actors there, and it showed most of the faults of the current system."

It doesn't take but a few folks getting shot in the back to turn citizens against the police force. Nor do alleged sexual assaults at gunpoint, questionable and coercive interrogations later thrown out in court, or cops on the take aid the image of Officer Friendly. Too many Austinites have come to expect to be stopped for driving while brown or black -- or, on the Eastside, driving while white -- and treated roughly. (Politeness to citizens is something they teach you in the Police Academy.)

And then there is APD's disturbing occasional propensity for excess, as in the notorious 1995 Cedar Avenue police riot: Responding to an "officer-down" call, more than 80 cops clubbed, pepper sprayed, and manhandled a group of black teenagers at a Valentine's Day party. The department has always insisted its response was appropriate to an attempted capital murder, and claims the federal-court acquittal of officers on civil rights charges vindicates APD. But the city felt enough culpability that it executed a still-controversial settlement of claims from Cedar Avenue victims. (Earle tried but failed to secure an indictment of the accused assailant of Officer Carlos Cardona, who needed more than 70 stitches to close a knife wound to the head.)

We saw the excess most recently at last month's Sixth Street Mardi Gras, where the line separating Officer Friendly from Occupying Force turned out to be pretty blurry. But Sheffield points out that on Fat Tuesday itself, three days after the Saturday night riot, he was beaned by a bottle thrown at him from the upper stories of a parking garage. "I wasn't doing anything but wearing a uniform," Sheffield says. "You want to talk about hate crimes? Officers have a good understanding of being hated and attacked for no real reason."

In Sheffield's view, the Mardi Gras police response -- which, so soon before the Meet and Confer vote, got a lot of people off the fence regarding police abuse -- was appropriate to the threat being faced by the cops. "We're attempting to stop fights, and for our trouble, people are throwing bottles and rocks -- and I'm not talking fish-tank gravel -- with the full intention of taking out police officers. And people seem to think we're supposed to just stand there and take it. People dehumanize the police because they hate what they represent. And it's dehumanizing to lump us into one big mass of uniforms and laws and procedures and call us 'the Cops.'"

Focus Refocused at City Hall

The Police Oversight Focus Group was a way to bridge the gap between Officer Friendly, the community-oriented cop Austin wants, and the Occupying Force, the no-nonsense police department Austin may need. At least that's how Spelman foresaw it. "The cops rely almost entirely on citizens for information," he says. "And if you're a cop and a large number of citizens don't trust you, it makes it difficult to do your job. So it's better in the long run for cops, as well as for members of the public, to trust each other."

Only an oversight system that is seen as legitimate by both cops and citizens could accomplish this. Hence Sheffield's service, along with two other APA-appointed officers, on the Police Oversight Focus Group. To widespread shock, after its appointment in June 1999, the POFG turned out not to be a Punch and Judy show, but as serious and thorough an effort to tackle a complex issue as has lately been seen in Austin. If every board and commission -- hell, if the City Council itself -- worked as well as the POFG did, we would all be happier.

Except, of course, that the POFG failed. Or did it?

Well, after months of public hearings, fact-finding trips to distant burgs, invited testimony from national experts, and work sessions that often lasted all day, Sheffield voted with the majority of the group that Austin needs a civilian oversight system. (Only former Mayor Roy Butler abstained.) So that's something. "We need and want an independent perspective to see that the department is truly policing itself," he says now. By that point, in November 1999, the group had settled on the outlines of the process adopted by the City Council earlier this month -- an appointed police monitor and civilian review panel which, under certain circumstances, will review APD's own internal investigations and disciplinary processes (see "Oversight 101," p.26, to learn how the new system is supposed to work). The final report didn't come out until last spring, at which point it was blessed by the soon-to-retire Spelman and then sent to the Meet and Confer table.

Since this was a consensus deal, born of obviously aggravating compromise -- mostly between Sheffield and del Llano -- things got left out, and those things have now come back to bite the city's political butt. Sheffield went to the mat at the Focus Group trying to impose qualifications on members of the Police Review Panel equal to those required of police officers. "I would not have a Pee Wee Herman or someone convicted of lewd conduct," he told the POFG. "Officers will say 'Absolutely no way.'" He was asked to drop this demand in return for del Llano abandoning her push for APD internal affairs and disciplinary records to be opened to the public.

But those qualifications came back during the Meet and Confer process, and they're part of the package the council just okayed. That's just one of the major differences between the POFG and Meet and Confer that have del Llano et al. all up in arms. Under Meet and Confer, the Police Review Panel and the Police Monitor will be appointed by the city manager, presumably with input from his subordinate the police chief, who in turn gets an earful from the APA president. Which means that -- in addition to the contract requirement that PRP members not be accused or convicted felons -- there can be any number of prerequisites, unwritten rules, and litmus tests for panel members, none evident to outside observers. (Panel members will also be required to undergo training to deal with the purportedly critical and complex legal issues they will encounter.)

The council tried from the dais to reserve appointment power for itself, but was told this would violate the city charter -- even though Meet and Confer agreements can supersede the city charter. And why the council couldn't appoint members of a police review panel, when it already appoints the members of the Civil Service Commission that hears disciplined officers' appeals, remains legally nebulous. (City Manager Jesus Garza did commit to appointing panel members from a pool referred by the council.) "If I could be God, I would fund giving each of [the council members] their own lawyers," del Llano says. "But when [City Attorney] Andy Martin turns and says that it's his official legal opinion that Beverly [Griffith]'s motion is illegal, then you're going to lose their votes. And they're not lawyers, so I don't blame them."

While nobody who wasn't at the Meet and Confer table seems thrilled by Garza's appointing the police review panel, ideas for how a civilian board should be chosen ranged all over the map during the POFG discussions. Del Llano and her Sunshine Project co-founder Scott Henson wanted a case-by-case panel convened from the municipal jury pool. This outline of a judicial proceeding, with subpoena power and cross-examination, "is the most apolitical way to do it," says del Llano, adding that jurors don't get any training to understand complex issues and seem to do well enough. But a judicial proceeding, said Sheffield and Spelman, was exactly what they were trying to avoid.

On the other hand, activists like Paul Hernández and the Rev. Sterling Lands felt that even a City Council-chosen panel was insufficiently independent, and called for the review panel to be elected by neighborhood groups, and/or constituencies with a history of harassment at police hands. This got shot down pretty quickly; the nation's top expert on police oversight systems, University of Nebraska professor Sam Walker, told the POFG that a council-appointed panel is the only way to go. Except it isn't, at least for Sheffield. A more explicitly political civilian-review process, Sheffield says, "doesn't work because it puts us at odds with the people we're sworn to protect and serve. Why civil libertarians would want to widen the gulf that's already there because of the badge, the gun, and the uniform, I don't know."

As for open records, state civil-service laws allow APD to keep its internal affairs investigations and disciplinary actions tightly under wraps, despite those being nominally public records. It took legal action by Henson to make public even the resolution (as opposed to the investigative files) of many of the cases that now dog the department, and which are chronicled on his APD Hall of Shame Web site (home.austin.rr.com/apdhallofshame). Only the disposition of "sustained complaints resulting in disciplinary action" -- defined by the Attorney General as suspension, demotion, or firing -- can legally be made public.

The APA and its sister police unions in the Combined Law Enforcement Associations of Texas (C.L.E.A.T.) have in the past gone to the Lege to get other records detailing officer misconduct not only shielded but destroyed. However, Sheriff Margo Frasier told the POFG that the Travis County Sheriff's Dept. (which doesn't operate under civil-service rules) makes all such records public as soon as investigations are completed -- as is true of regular criminal investigation files -- with no undue effect, negative or positive, on department management.

Had it been swallowed whole during Meet and Confer, the POFG recommendation would have allowed APD internal records to be reviewed, post-discipline, by the complainants, the monitor, and the police review panel. The panel would hold its meetings in public, and the monitor could report directly to the City Council. But those provisions came out in the Meet and Confer wash; the system just established by the council allows for no public hearings, no reporting on individual cases to the council, no access to IAD files by complainants, and only limited access by PRP members. "It's reasonable to say oversight has worked if the people who've identified problems think we've solved them," says Scott Henson. "Right now, they won't even know. Even if APD's system worked so well it cleaned up the whole department, who could tell?"

Sheffield counters that "right now, the chief can tell Internal Affairs to investigate this officer for that reason, and trust me, they'll be very thorough." He adds that officers are routinely compelled to testify before IAD, whether such testimony is self-incriminating, and to submit to warrantless searches, not only of their workplaces but of their homes, or lose their jobs. "If you do what some have wanted" -- make the records of those investigations public -- "the officer will say 'I'll cooperate to the degree it doesn't interfere with my Fourth, Fifth, and 14th Amendment rights.' You'll end up learning less, not more."

Who Let the Dogs Out?

While it's hard to imagine previous APA leaders sitting across a table with Ann del Llano for months on end, Sheffield is still a union boss tasked with protecting the boys and girls in blue (which in Austin is actually black). So when the POFG recommendations went to Meet and Confer, Sheffield (and 17 other officers on the APA team) had a second chance to tweak them to the union's -- and, it cannot be overstressed, management's -- liking.

Del Llano had seen this coming, and asked that other POFG members be allowed to sit in on Meet and Confer talks, a request greeted by the city with something approaching a snort. But she also felt that during the POFG, "Sheffield acted as an official negotiator for the union, with his own lawyer and everything. He told us in public what his officers could and couldn't do. So we felt that he was working out this tiny part of [Meet and Confer] in public."

Now, in places where unions -- especially of public employees -- are not quite such a novelty as in Texas, they're expected to bargain for their members' interests and no others, and interested stockholders aren't sitting at the table when GM talks to the United Auto Workers. "What we came up with [in Meet and Confer] was something that we thought our members could live with," Sheffield says. "It's negotiation. It's all about compromise. I don't know why we can't see how this works before we condemn it to failure. This process, I really do believe, will do the most good for the most people."

Likewise, the idea that management could simply void and replace major elements of a negotiated labor agreement, unilaterally -- which is what Beverly Griffith tried to do from the dais on March 8 -- would be appalling in places where labor rights are as cherished as civil rights. But if the council really wanted the POFG plan, and not a simulation, to be part of Meet and Confer -- had they been snowed, and thus were they justified, in trying to un-negotiate civilian oversight?

In fact, the record shows that the council directed Garza to include citizen oversight -- but not a specific plan -- in Meet and Confer, and Spelman and others felt the POFG plan was a starting point, not the last word. Nor did Sheffield hide the fact that, as he said at the end of the POFG process, "Officers are still very, very skeptical about this deal." But the City Council -- after Spelman left office -- got regular briefings about Meet and Confer, and if anyone at that table could be held to heel by the council, it was Garza and Stan Knee (or, actually, their respective deputies, Toby Futrell and Mike McDonald). So if the city got snowed by Mike Sheffield, it didn't seem to mind that much while it was happening.

Concerning the open-records issue, "there's a coincidence of interests between the city manager, the police brass, and APA," says Henson. "And that confluence of interests subverts the public interest. The union doesn't want information released because they have a record of strongly protecting the worst offenders and never let them get fired. The city manager's interest is to limit the city's liability and political blame. And APD brass are who we're saying aren't doing a good enough job of oversight now. So, without a POFG voice at the Meet and Confer table, they could all agree this was the best way to do it."

But if the APA was so successful at bending the POFG proposal into its preferred shape, then how come 40% of the rank-and-file voted against a Meet and Confer agreement that included such an enormous pay raise? Henson talks of unrecognized support for oversight within APD, but that's probably not the whole story. Sheffield notes that the union didn't succeed in improving cops' health care benefits, but that's probably not the whole story either.

To complete the picture, you need to look at the good ol' boys on Sheffield's right flank, the aforementioned Occupying Forces who think Officer Friendly is leading APD straight to hell. Prominent among these is Randy Malone, a now-retired officer who formerly served on the APA board, then tried to organize a Fraternal Order of Police local to compete with the union as, in Malone's view, the APA drifted left. (Malone is the officer who filed a report naming former chief Elizabeth Watson as a criminal suspect because she took him off the Sixth Street hot dog wagon beat. He also made headlines when his FOP chapter's telemarketing campaign turned out to have a 70% overhead cost and got in trouble with the Better Business Bureau.)

Unsurprisingly to Sheffield and other APA leaders, Malone put in extra effort trying to turn the rank-and-file against the Meet and Confer, saying its oversight provisions amounted to a wholesale trashing of officers' hard-won and God-given civil-service rights. "This agreement doesn't say a lot of the things that either Randy Malone or Ann del Llano says it does," Sheffield says. The word from the cop shop now is that Malone is recruiting challengers to Sheffield's presidency, possibly Ernest Pedroza, leader of the Hispanic officers' organization Amigos en Azul. (A campaign to actually recall Sheffield for "dereliction of duty" has apparently fizzled.)

Hoping to Build Trust

The Meet and Confer agreement does include other ways APD could end up where oversight advocates want it to be. For example, under civil-service law, promotion to sergeant -- that is, to supervisor -- only requires passing a written exam. In the previous Meet and Confer agreement, the city secured a requirement that senior managers -- lieutenants and above -- be assessed for promotion based on their actual performance, just as in your workplace. The new agreement extends this requirement to sergeants as well, and the city is touting this as a huge management gain.

APD Chief Stan Knee, and Elizabeth Watson before him, have made community policing the order of the day at APD, and under an assessment system the sergeants actually training the new and young cops -- a disproportionate share of Austin's police force -- are now more likely to be Officer Friendly. "Having an intelligent way to select first-line supervisors is by far the most important thing you can do to get culture change in APD," says Bill Spelman, "and the Meet and Confer goes a long way in getting there."

"In the long run, oversight is going to be extremely important," Spelman went on, "and I would have preferred a system such as that outlined by the POFG. But if Stan Knee had to make a choice [between oversight and assessment], he made a defensible one. There's a certain number of chips he's got to spend with the union. I wish he had a few more chips." (While Knee said he'd support any oversight system that didn't pre-empt his freedom to discipline officers, he's been reticent to discuss his personal commitment to civilian review. Mike McDonald, however, endorsed the POFG plan when it first went to the City Council.)

According to Henson, Knee needs enough chips to tackle the biggest structural flaw in the system, one that wasn't even touched by the POFG -- the almost limitless ability of even the worst cops to get reinstated to the force through the civil-service appeals process. (For example, the firing of accused rapist Samuel Ramírez was overturned because Knee took six days instead of five to inform Ramírez of his "indefinite suspension.") As Henson told the POFG, "The problem isn't that we have so many bad cops, but that we can't get rid of them." But, Henson notes, "the APA told us from the beginning that the appeals process was off the table, and that's the real deal. Even if Knee wants to fire people, he can't do it. And look how aggressively APA has defended the worst of the worst. That's their true stripes. They need to tell us how to get rid of the bad guys. If you're not doing that, you're not helping, no matter how liberal you are."

Sheffield, the liberal in question, says "the APA isn't here to defend people when they're right or wrong, but to protect their access to due process. And that's what we've accomplished. The ACLU should be more attuned to the right of due process. But when it comes to us -- we have no rights. Police officers already give up so many of their rights that we cherish the ones we have left."

So if the point of civilian oversight is to expose the sleazebags and goons and get them off the force, it's already starting with one hand tied behind its back. Indeed, according to del Llano, what's in the Meet and Confer is a big step backward. "There are now more opportunities for the victims of police misconduct to incriminate themselves," she says, since their statements to IAD and the police monitor are not protected from use in court, as are the statements of officers. "And there is now a sham organization that people can point to and say we've answered this question in Austin. And the saddest part is that the City Council signed away all of their authority over this forevermore." Since the Meet and Confer supersedes city ordinance, even if the Council wanted to amend the charter, it's too late -- unless the new system is so wanting that the APA can't stop the city from imposing a tougher line in the next contract.

But there is another way to look at oversight. In San Jose (whence the POFG derived many of its ideas about the police monitor), the position is actually called an "auditor," and much of what she does is statistical analysis, identifying particular patterns and problems that call for systemic solutions. And Austin's police monitor has a measure of the same power. "If what you want is to make APD, from the chief on down, aware of what the community's priorities are, and how they may differ from the department's, the oversight process in the Meet and Confer will get you to that," Spelman says. "And if we pick the right monitor and the right board, and then pick the right patterns to look at, in a couple of years" -- that is, when this Meet and Confer agreement expires -- "you'll have built some legitimacy for this system with both the cops and the public."

By that time, Mike Sheffield may have retired, closing in as he is on 25 years of service to APD, and who knows which way the APA wind will blow. Even his adversaries acknowledge that he would be missed. "I've always had a very cordial relationship with Mike Sheffield, and I enjoyed working with him on the POFG," says del Llano. "Mike is intelligent enough to realize what's going on elsewhere in the country about oversight, and he realizes that the police officers have to do something to build trust with the public. And he's doing a lot of things that would help. He definitely represents a new way of thinking for the union." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.