Sterling Lands' New Mission

The Eastside Social Action Coalition Confronts the Public Schools

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Jan. 12, 2001

Late Sunday morning, a blues beat escapes the walls of Greater Calvary Baptist Church in Northeast Austin, flooding outward into the parking lot. It's an infectious and swelling music, inspiring those running late for the noon service to quicken their pace up the short flight of steps leading to the main chapel. Inside, the children's choir is belting out spirituals, accompanied by a full band: horns, piano, drums, with guitar and bass as movingly rendered by two pastors at the pulpit. Senior pastor Rev. Sterling Lands II has his eyes closed and his head bowed, in concentrated intensity over his guitar. He rocks slightly with the beat of the music, and every once in a while his eyes open, revealing a sedate and beatific look. As the children sing, the congregation members in the chapel are clapping, dancing, stomping their feet, and calling out "Amen!"

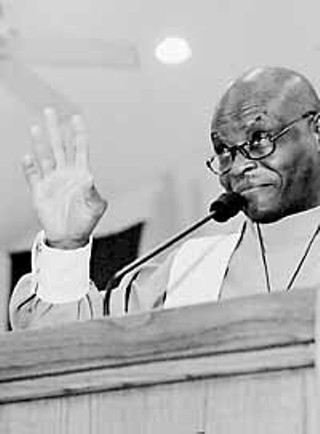

After the choir finishes and announcements are made, Rev. Lands takes the pulpit. His long blue denim dashiki sways around his legs as he addresses the audience. He's worried, he says, about the lack of moral authority in society, about the relativism that pushes people to claim there are no moral absolutes. His strong tenor voice resonates throughout the chapel, in a blend of relaxed, conversational scriptural scholarship and entrancing emotional intensity. "Sixty-seven percent of the people say there is no such thing as truth," he says, his voice billowing through the hall. "Seventy percent say there are no such thing as moral absolutes. No matter what your station in life," he adds incredulously, "you cannot go forward without morals. Is anybody listening?"

His voice rings out as he probes the crowd with a lightning gaze, his brow furrowed slightly, a small trail of sweat beading on his right temple. "We hear you, pastor," and "Amen," burst repeatedly from the crowd of about 100 people, alternately rocking back and forth on their feet or clinging to the edge of their seats. For nearly 45 minutes, Lands keeps them this way, and he's right in it too -- sometimes eerily not of the room, a distant look instead training his eyes upward. The spell is rapturously carried through to another round of bluesy spirituals as the Anointed Voices Choir takes the stage and Lands moves back to his guitar, head bowed again, brow smoothed, eyes closed.

When the service ends, the crowd remains pumped. Churchgoers wander among the pews hugging, kissing, and blessing one another. Lands is at the front of the crowd, his smile beaming and his eyes alight underneath salt-and-pepper brows. "This is what I do, this is who I am, you have now seen the real me," he says, his voice an energetic bullet fired across the room. "People, they call me an agitator ... because I do, I do do that."

As a community activist for the past 16 years, Lands has never been afraid to pit what he sees as right against wrong. From helping open a dialogue between East Austin residents and Austin Police Department officials concerning police brutality issues to forming a group of neighborhood residents and church members to clean up graffiti, Lands is determined to make a better life for Eastside residents. Most recently his voice has reverberated out of Greater Calvary's chapel all the way over to West Sixth Street, where, as the official spokesman for a fledgling Eastside activist group, he is delivering a hard-line message to the administration of the Austin Independent School District. Discontinue a legacy of racist and unequal public education, say Lands and his community allies, or suffer the public, political, and financial consequences.

46 Years After Brown

It is Sterling Lands' ministerial ability to move from the fevered to the sublime in one seamless swoop that underlies the intensity of his current public mission. As president of the recently formed Eastside Social Action Coalition, Lands and his group of nearly 600 members have taken on the often lumbering bureaucracy of AISD in the name of the schoolchildren of Austin's Eastside. The Coalition (formed originally in 1998 to respond to police brutality issues) charges that the district is failing miserably to educate African-American children. In an Oct. 30 letter to AISD Board of Trustees President Kathy Rider, Lands and the ESAC charged that "46 years after Brown [v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 federal court case that ended official school segregation], our schools are still separate and still unequal." The Coalition demanded the school board take immediate action on a list of 20 priority items aimed at correcting what it sees as the structural inequities in local public education. Moreover, in submitting the letter, the Coalition warned publicly that in the absence of an adequate response from AISD, Coalition members were ready and willing to withdraw their children from the public schools.

The range of the demands varied from the broad ("Implement character development throughout the curriculum") to the specific ("100% parity and equity of teacher and administrator pay across color and gender lines"), but all shared a common thrust: the conviction that the district is failing to educate minority children, and that something must be done, immediately (see "Still Separate and Still Unequal," p.26). In the Coalition's judgment (confirmed by their recent study of AISD and Texas Education Agency statistics), minority students -- particularly African-American children -- have been institutionally ill-served by the city's public schools. By most academic measures, African-American students consistently perform more poorly than white students, and are much more likely to drop out of high school. While there is certainly more than one possible explanation for these persistent conditions, the Coalition points most directly at the schools and the district administration. "Unless you believe that children of color are inferior in their ability to learn," Lands wrote, "you must conclude with us that we have an emergency of horrible magnitude and immediate and deliberate action is required to reverse the trend."

In submitting the Coalition's initial letter, Lands requested that AISD respond with a complete implementation plan no later than Nov. 8. (Each individual item also carried a specific deadline for AISD action, with a few -- such as the demands for reductions in minority students shunted to special ed or disciplinary classes -- requested to occur by Nov. 15.) That initial deadline has come and gone, and since November, Lands and the Coalition have emphasized their desire to solve the problems in a cooperative fashion. "This is important, and I would like to see this thing work out in a way where it does not have to become an all-out conflict," Lands said. "This city should be progressive enough in its beliefs about civility that it should not be necessary to air so much dirty laundry."

But the potential consequence promised by the Coalition -- that if necessary, members would withdraw their children from AISD schools, educating them instead in the community's churches -- is no idle threat. Indeed, since school funding is tied closely to actual enrollments, such a move could potentially cost the district millions in federal and state monies.

Mindful of the seriousness of the charges as well as the potential consequences of inaction, district officials promptly arranged meetings. The first was held Nov. 30, when board president Kathy Rider (along with board vice-president Doyle Valdez and board member Olga Garza) sat down for a discussion with Coalition representatives. They had time to address only two of the Coalition's action points, but both board and Coalition say they intend to keep talking. A second meeting was held Jan. 9 (see Naked City for "The Fire This Time," p.18). "It has stopped us from going any farther with this action and we are, in good faith, meeting," Lands said during a December interview in his office at Greater Calvary. "We recognize that we only meet as long as people are willing to work toward a win-win solution. If we feel that the meetings are just to pacify us, then all bets are off. That is our position."

Equality, Equity -- and Race

In her office across town from Calvary Baptist, on the third floor of Franklin Towers off West 35th Street, AISD Board of Trustees President Kathy Rider sat in an armchair, reviewing the letter Lands gave her at the end of October. Rider is a clinical social worker by trade, and has been on the nine-member board of trustees since 1992, when she was elected vice-president. She became president in 1994.

Her manner is matter-of-fact. "My initial reaction, when I read the whole document, was that he has some points that are mutually agreed upon. We have lots of concerns about the achievement of African-American kids," she said. "So he has brought forth a lot of issues that have concerned the district for some time. But his particular timelines, and some of the things he asked for, I felt were unrealistic." Rider said she has been concerned about the disproportionate number of African-American students assigned to special education, for example, as well as what she calls the "inconsistent" leveling of discipline, especially at the middle school level, where offenses that land kids in the Alternative Learning Center campuses (where behavior problems are addressed) vary widely from school to school. However, she insists, the process to correct these things takes time, certainly more than the two weeks the Coalition demanded. "For example, removal of 75% of African-American kids from special ed by Nov. 15," she said. "Not only would the Feds be on us like a duck on a June bug, but the parents would not be happy either. The kids that go into special ed are referred from teachers or parents and they have to meet certain criteria, which are federal criteria."

On the other hand, Rider described other actions the Coalition has demanded as simply without merit. Particularly she indicated item 17, which requests "100% parity and equity of all resources and materials at all East Austin schools by or before August 2001." According to Rider, all campuses in the district already receive equal funding from the district's budget. Indeed, according to the district's funding formulas, each AISD student is allotted the same number of dollars: $71 per high school student, $64 per middle school/junior high student, $59 per elementary student. School staffing formulas are also standardized across the district, based upon grade level.

The district funding tables were compiled in a response to each of the ESAC's demands, and a letter with the responses was delivered to Coalition members at the Nov. 30 meeting. "It is certainly a common perception -- and we have to remember that people's perceptions are their realities -- so, when we look at the Eastside Social Action Coalition memo, we see it is certainly their reality that there are more resources west of I-35 than there are east of I-35," Rider said. "But we have to say what we're defining as 'resources.' If you're talking about the income levels of the parents or the families that send kids to a particular school, then that's one thing. We don't control that." However, board member Loretta Edelen, whose District 1 seat represents much of East Austin, said that for most of her six-year tenure she has been concerned with making sure additional resources find their way into the district schools that have the highest percentage of economically disadvantaged children. "We need to make sure we are focusing more resources for the neediest children," she said. "Those are the key issues I try to focus on."

The district has made some headway, notably by pumping additional money into schools primarily serving poorer families. Federal Title I grants provide resources to lower-income schools, and additional federal grant money has been channeled to the same schools through a two-year-old district program called Account for Learning, with funds going for lower class sizes, additional curriculum specialists, parent training specialists, and additional educational materials. Funding allotments are based on the number of students at each campus eligible to receive free or reduced lunch.

So, in practice, some Eastside schools do receive more money than their west side counterparts. For example, at Reagan High School, where 57.8% of students were classified as economically disadvantaged, per pupil spending hit $4,686 for the 1999-2000 school year. In contrast, at Austin High School, where last year 17.1% of students were identified as economically disadvantaged, per pupil spending was $4,163.

However, despite the district's straightforward funding formulas, ESAC members still see the schools as separate and unequal. The roots of the inequity are not based in district funding allotments, they say, but in Austin's racist past and -- to a lesser extent, perhaps -- present. "Whether you call it 'racism' or not, we do have inequity," said coalition member and newly elected Austin NAACP President Nelson Linder. "The black community has never been taken seriously by the school district, we've been taken for granted. I think it is due time they understand we have issues too."

For the black community, Austin's current reputation as a "liberal" city is only persuasive by rather provincial Texas standards, and minority citizens have good historical reasons to be skeptical of official declarations of racial magnanimity. According to a report on "Ethnic and Race Relations in Austin" (released in September by UT's Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs), even after the end of legal segregation African-Americans and Hispanics were effectively zoned into particular residential pockets of the city, and therefore out of many city resources and services. Historically, African-Americans were zoned primarily into East Austin, the heart of the city's industrial section. "In essence, by concentrating various services for Blacks in East Austin, the city used service delivery to accomplish what zoning laws constitutionally could not," researchers found. Further, the report quotes AISD Area Superintendent Glen Nolly as saying Austin's race issues have often been less offensively couched in economic terms, which describe "disadvantaged" or "at-risk" populations. "What's happening now is that we are lumping everyone in this category of 'economically disadvantaged,'" Nolly told the LBJ School researchers, "and not paying attention to race, and race is still there simmering."

With such a recent history of indifference and neglect by the city, Lands said, it is little wonder East Austinites still feel the aftershocks of a not-so-distant past, and that remnants of Austin's officially segregated past can still readily be found in AISD. As an example, Lands and Linder both point to the demise of the old L.C. Anderson High School. In 1971, recently enough to be fresh in the memories of many East Austin graduates, Anderson was moved to the west side. To add insult to injury, all the trophies and other marks of accomplishment that the historically black school had earned over the years were left behind, locked in a district storage shed. At AISD headquarters on West Sixth Street, old Anderson High may be mostly forgotten, but east of I-35, the memories linger. More recently, Lands points to the delays in removing asbestos from the Eastside's mostly minority-student Pearce Middle School.

But most glaringly of late, Lands and the Coalition point to the increasing -- and increasingly public -- tensions over the placement and operation of the school district's three "magnet" programs.

De-Magnetized?

In the early Eighties, magnet schools -- specialized advanced academic programs at the middle and high school levels -- were assigned to low-enrollment Eastside schools as part of a last-ditch, noncoercive attempt to desegregate Austin schools. In theory, magnet programs "integrate" the schools by attracting students from across the district, either to the advanced curriculum Science Academy at LBJ High School, the Liberal Arts Academy at Johnston High School, or the magnet programs in both humanities and math and sciences at Kealing Junior High. Students are accepted into the three current magnet programs based on their prior academic performance.

But in practice, "integration" is often more theoretical than real. Each program is operated as a school-within-a-school, creating tensions between magnet and neighborhood school administrators, parents, and students. The tensions are sometimes territorial, but also can reflect real conflicts of interest within the schools. Parents of the mostly minority kids in the "regular" academic programs at the host schools say the neighborhood student education generally takes a back seat to that of the magnet students, who are predominantly white. "This [institutional inequity] is in line with this whole discussion," Lands said. "And this is just the beginning. You are going to find that parents will not sit by in a high tech society and watch their kids being prepared to be uninformed consumers and a potential minimal, menial labor force. We are just not going to let that happen."

Predictably, some magnet parents hold a strikingly opposite yet equally unhappy view of the current state of the advanced academic programs. They feel their children's education is suffering because of the lack of attention the programs receive, lack of physical space available for conducting classes, and administrative disruptions at the schools-within-a-school. All three of the magnet campuses indeed have been plagued by administrative turnover -- Johnston High has had six different principals in seven years.

Some parents say such instability undermines their children's educational needs, and they're not above borrowing the language of the civil rights movement to defend their position. "All the magnet students, teachers, parents, and community want is their home -- home for a sixth grade, a middle school, and a combined high school program and the freedom to teach to our students' needs," one magnet parent wrote in a note to the Chronicle. "For God's sake, let us have our home, too, and free us! Free us at last!" In recent months a movement by Kealing Junior High magnet parents and teachers to separate the Kealing magnet into its own, in-district charter school has been gaining steam, with a formal request now pending before the AISD board, scheduled for a vote in February.

Called to Leadership

Sterling Lands II is 56 years old, and has lived in Austin since 1984, when he became the founding and senior pastor of Greater Calvary. He had been a process-control engineer in St. Louis before being called to the ministry 25 years ago. "You never just take this kind of thing on," he said. "It is always a calling." Through the church he also presides over two schools -- a learning center for two- to five-year-olds, and a grade school for kindergarten through third grade -- as well as the "Rites of Passage" program, which teaches discipline to young African-American males. Long active in his neighborhood and in city politics, he has been an active member of AISD's Dropout Task Force, and currently serves on the city's Planning Commission.

"Lands does an excellent job. He has lots of programs in his church and does a lot of outreach in the community," says City Council Member Danny Thomas, who appointed Lands to the Planning Commission. "He's always been active, ever since he's been here. I have nothing but high things to say about the guy. He gets many things done in the community." Lands' reputation as a "dynamic" and "persistent" leader crosses racial and official lines, and even those who have wound up on the receiving end of his "dynamism" recognize him as powerful figure. "I find Rev. Lands is very straightforward," said AISD first-year trustee Ingrid Taylor. "He listens and is challenging in what his analysis is and expectations are. That's very welcome." Lands was chosen as president of the Eastside Social Action Coalition by its then 300 members, just over a year ago. The Coalition had begun with just 25 people who came together, Lands said, in "protest and prayer" over police brutality issues in East Austin.

Less than two years later, the group has grown to include 600 members -- civic and religious leaders, parents, kids, and teachers -- who are finding strength in a renewed, vigorous Eastside activism and in a leader they say has the vision and humility to get things done. "We are doing something that requires passion and skills, and you need someone for it who has that vision, those passions, and those skills," said Eastside activist and organizer Rev. Frank Garrett Jr. "[Lands] has the passion. He says, 'Let's get the job done.' He's the leader and the servant. When you are the leader you must serve the people you lead -- and Lands is all that."

Breaking the Belief System

The coalition's scrutiny of AISD intensified last spring, in the aftermath of the dismissal of LBJ High School principal Sylvia Lewis, who had been in charge of overseeing the school's Science Academy magnet program as well as its regular academic programs. Lewis did not leave willingly, and last summer sued the district for wrongful dismissal. Because of the pending court action as well as the district's institutional reluctance to discuss personnel matters, the details of Lewis' firing are still unclear. Predictably, the official and the neighborhood versions of what happened radically diverge.

District officials told the Austin American-Statesman that Lewis was let go as a result of concern about "instructional integrity and preserving the educational environment." School Superintendent Pat Forgione said, "The issue I heard is someone's got to develop a working relationship with two faculties within a campus and get them to work together and share together." But Coalition members saw Lewis' dismissal as retaliation against a black administrator they believe was trying to equalize the resources of the magnet and regular programs. The firing "was done in a very cavalier and inhumane way," said Lands. Lewis was escorted off the campus in the middle of a school day in the late May, in front of both students and school staff. "Whenever you want to break a belief system, you have to take drastic action. Here you have kids that are already thought to be on the fringe by some -- and they had very tremendously high regard for this principal. So if you want to destroy that, it's psychological warfare," Lands said. The incident galvanized the Coalition into action -- nearly 500 people packed a June 5 public meeting with Forgione, and "we've been going strong ever since," Lands said.

The incident also ignited already sensitive feelings regarding the magnet schools. A 736-page AISD audit completed by state Comptroller Carole Keeton Rylander last spring had urged the district to consolidate the two high school magnet programs into a stand-alone school that, suggested Rylander, could be housed in the currently "under-enrolled" Reagan High -- also an Eastside campus. Echoing the growing feeling among magnet-school parents, Rylander also recommended turning Kealing Junior High into a magnet-only program. Reaction from the Coalition has been swift and angry. "We will not tolerate the stealing of Kealing," Lands said in early December to a Coalition rally of about 50 people outside Kealing, garnering a robust ovation from the crowd.

But in what might seem a contradiction, the movement by the Kealing magnet parents petitioning the school board to create an in-district charter school for the magnets -- outside the Eastside schools where they're currently housed -- has also come to coincide with the Coalition's recently stated wishes to return the Eastside campuses to strictly community-based, neighborhood schools. "I think that is probably going to be the best thing for Austin," said the NAACP's Linder. "We don't need them. To me [the magnet program] is elitist."

Moving the magnet programs elsewhere, outside the Eastside schools, might temporarily answer the pressures on all sides. But it would also effectively abandon any potential function of those programs as "integrators" of the Austin school community and neighborhoods. But perhaps that's not such a big loss. Frustrated as they are by years of such small progress in minority student education, Eastside parents no longer necessarily see integration as a first priority. Lands said the Coalition would prefer to see "integration" through an across-the-board heightening of academic rigor, which he believes would effectively make the magnet programs obsolete. Coalition members hope that by returning to exclusively neighborhood schools, minority kids would receive more direct academic attention. Currently, "there is not a balance of resources and in the skill levels of the teachers," said Coalition member Edgar Whitfield, who was also on the interview committee that helped select candidates for the new LBJ principal following Lewis' dismissal. Academic rigor in itself -- for all students -- underlies all the items the Coalition says AISD needs to address. "The district will have to restore a standard of excellence for all children that will serve as a beacon of vision that inspires the kids and the community to higher heights," said Lands. "And that's doable."

District officials quietly agree that there is a lack of academic rigor across the district. "Academic rigor is a problem at all our high schools," Rider said. "In general, we've allowed it to happen. We've not kept our eye on the ball for rigor in the regular programs, and have put more focus on the TAAS [Texas Assessment of Academic Skills test] and upgrading the [honors and Advanced Placement] curriculum. We're trying. We certainly did not mean to neglect any particular population." The board has placed academic rigor on the district's "critical issues" list, and has formed a working group to analyze district-wide standards and to make improvement recommendations.

All this movement makes Lands and the Coalition cautiously optimistic. Indeed, thus far the district has been formally attentive to Lands' group, meeting twice in as many months. "It's a beginning dialogue," he said. "And we do want to be good participants, but ..."

No More Patience

As a crowd of neighborhood school supporters rallied outside the Kealing campus, Lands joined the gathering crowd, clasping peoples' hands and offering warm wishes and thanks for attending. Standing on the curb near the Pennsylvania Street entrance to the school, he addressed the group: "You either have to stand for something, or you'll fall for anything. Every minute we waste, we've lost another child." Afterward, Lands was rarely without a supporter at his side, as he fielded questions about the Coalition's next steps. Currently, he says, those steps include not only preparing for the group's next meeting with the district, but also preparing for "the worst": pulling children out of public schools and placing them in community church schools.

"When people say, 'Why are you so impatient?' I say, 'Are you kidding? I need to be flogged -- we should've been doing this 15 years ago,'" Lands said. "If we can't see significant progress in this fourth six weeks [of the school year], which is right around the corner now, then we are preparing, actively preparing, to educate our own kids."

There are already several private and charter schools operating in Eastside churches, including the two private academies at Greater Calvary. Lands said the Coalition has lined up a handful of churches ready to serve as neighborhood schools, and that the group is currently devoting time to developing a curriculum, as well as lining up retired AISD teachers and substitutes who have offered to help. While there is obviously an abundance of dedication and energy associated with the Coalition and the parent-activists, it's very uncertain how realistic or sustainable a massive effort at "private" schooling would really be. Lands, unflappable in his insistence that the Coalition can handle whatever comes its way, scoffs at any suggestion that the task is impossible. "We don't have a choice, this is our kids we're talking about," he said. "This is their future."

However realistic the long-term, large-scale threat, it is safe to say the proposition of a large number of Eastside minority students fleeing the public schools makes district officials uneasy. Not only would it be a terrible public relations nightmare, but the district would stand to lose a significant chunk of the nearly $13 million in federal grant money it receives each year. Moreover, because of per-student funding formulas, such an out-migration could significantly raise the amount the district would have to return to the state under the state's Chapter 41 legislation (the "Robin Hood" law).

Chapter 41 mandates that wealthier school districts (defined by taxable property value), must share their funds with poorer districts, with any district's "wealth per student" currently capped at $295,000. When Austin's hot-market value of $30 million is divided by AISD's 79,000 students, the wealth-per-student ratio comes to just over $385,000, well over the legislative cap. With property values still skyrocketing, the loss of any significant population of children would put an additional fiscal burden on the district. Kathy Rider does not deny she is troubled by the prospect. "My first response [to the possibility of children withdrawing from the public schools] is that it is not in the best interest of the kids, even though I will go to my deathbed supporting the right of parents to do what they feel is best for their children," Rider said. "It would sadden me to have a group of folks to have such lost faith and confidence in the district that they'd pull their kids out of the schools."

But parents in the Eastside Social Action Coalition don't see removing their children as such a devastating step, if it improves current students' education -- and applies the pressure needed to make the district change for the benefit of future generations of minority students. Edgar Whitfield's son is a senior in LBJ's magnet program, yet he says that should it become necessary, he will join the other parents in the Coalition in removing his son from AISD. "Although he is a senior, it's the environment for those who follow him that's important," Whitfield said after the recent Kealing rally. "I can't be myopic in my view. We need to create the best environment for all students."

Moreover, other parents argue, the education their children would be receiving is -- at least at this point, in the admittedly small-scale, church-housed private and charter programs -- superior to that currently available in the Eastside's public schools. At Greater Calvary, Lands said, curriculum in the two private schools (with a combined enrollment of about 50 students and growing annually) is based on Montessori-style teaching. "It's exploratory and it deals more with, 'Let's stretch kids,'" he said. "It brings out what is in a child, as opposed to making the child try to fit into a mold." Coalition supporter Jenniffer Muhammad -- who, along with attorney Michael Bryant, was instrumental in establishing the Youth Millennium Complex -- has three children enrolled at Greater Calvary, and is very happy with the education they're receiving. "We just have so little faith in AISD's ability to educate our children," she said. "My five-year-old reads, my five-year-old does double-digit math problems, and he's already been introduced to differential calculus. [Greater Calvary] doesn't limit the children. They don't tell you that you can't -- they tell you that you can. And if they tell you that you can, you will. I have a lot of respect for Pastor Lands."

Back in his church office, Lands sits at his desk, behind a pile of unanswered phone messages, holding up a portrait of his family: Mable, his wife of 33 years, their two sons -- both pastors at Greater Calvary -- daughters-in-law, and three grandchildren. "And another grandbaby on the way," he smiles, his liquid brown eyes glinting. "I sound like a grandpa, don't I?" He's doing this for them, he says, his eyes taking on the seriousness and urgency of his tone. "This is going to be win-win, there's no doubt about it," he says. "Win-win to me means the kids are in an environment where they can thrive. That's win-win. It is possible within AISD -- if the philosophy changes. I don't think they have a choice." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.