Not Clucking Around

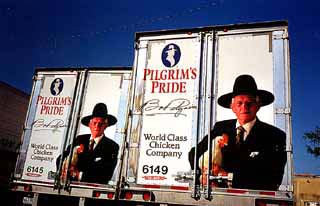

Texas Poultry King Bo Pilgrim Takes on Senate Finance Committee Chairman Bill Ratliff

By Robert Bryce, Fri., Nov. 3, 2000

If Jesus can bless Bo Pilgrim with a new jet airplane, why can't He help Bo with his Bill Ratliff problem? It might soon require a Higher Authority to intervene on behalf of Pilgrim.

There is no doubt that East Texas chicken magnate Lonnie "Bo" Pilgrim is flying in style. Last December, in his company's monthly newsletter, he sang hosannas to his new corporate jet: a $12 million aircraft that seats eight passengers and can cruise at 600 miles per hour at 41,000 feet. "I want to thank Jesus Christ for our new Hawker 800 XP airplane," says Pilgrim in his "Comments From the Chairman" epistle on the back of the glossy newsletter. After explaining that the company has another plane, a KingAir 300 that it has used for 16 years, and that he put a Bible in it shortly after it was purchased, Pilgrim continued. "Another Bible has been added to the new airplane, thanking Jesus. We are now operating both airplanes for our company which always praises Jesus."

The newsletter doesn't mention Bill Ratliff, the powerful state senator from Mount Pleasant, which is no surprise. Ratliff and Pilgrim are among the most powerful men in East Texas. They are also enemies. Their five-year-long feud has divided loyalties in both Titus and Camp Counties, which together are the production center of Pilgrim's $2 billion-per-year chicken empire. And while Pilgrim continuously invokes the name of the Lord, he has some un-Christian things to say about Ratliff, including charges that he is a liar and a racist. Ratliff, for his part, says that Pilgrim doesn't care about the environment, and that his long record of pollution violations proves that.

The two men are unlikely foes. Both are conservative, pro-business, pro-George W. Bush Republicans who live within a few miles of each other in the hilly woodlands of East Texas. Both proudly identify themselves as Christians. They are wily politicos who know how to work the system. They are about the same size, near the same age (Pilgrim is 72, Ratliff 64), and with their gray hair and glasses, they even look a little bit alike. There's another similarity: "They're both more than a little hard-headed," said a lobbyist who knows them both.

The focus of their latest quarrel is a permit pending at the Texas Natural Resources Conservation Commission (TNRCC), which if approved will allow Pilgrim to nearly double his East Texas chicken-processing capacity. A new plant he proposes to build on a 4,000-acre tract in northernmost Camp County will be called Walker Creek Village and will include a slaughterhouse capable of processing two million chickens per week, a prepared foods factory, and a rendering plant. (Pilgrim's Pride prefers to call it a "protein recovery facility.")

Hundreds of new houses for workers will also be built. The project will cost the chicken company over $100 million. If it goes forward, it could mean an additional 2,000 jobs for the region, as well as tens of millions of dollars in new economic activity. But it will not be built unless Pilgrim obtains a state permit to allow his company to inject three million gallons of slaughterhouse waste per day into six injection wells located in northern Camp County.

Pilgrim's Pride vice-chairman Cliff Butler says the water they will be injecting is "almost fresh water." Perhaps it is. But it's also clear that Pilgrim has no other choice but the injection wells. The company cannot discharge any more wastewater into Cypress Creek, which is already receiving over three million gallons of wastewater per day from Pilgrim's existing slaughterhouse operation.

While the houses at Walker Creek are already under way and the land for the project has already been purchased, it appears Pilgrim has made a critical mistake: He bought the land without checking to see who owns the land on the other side of Cypress Creek. The 600-acre tract that sits just north of Pilgrim's planned rendering plant is owned by the Sandlins, one of the most prominent families in Titus County. Bill Ratliff's wife is Nancy Sandlin Ratliff. When the Walker Creek project was proposed, the Sandlins asked Ratliff to fight the permit, and the senator agreed. "It appears to be a selfish interest," Ratliff acknowledged during an interview in his office in Mount Pleasant last month. "I don't apologize for it."

And this is where this story gets interesting. Ratliff, the conservative Republican who has an outside chance of being the next lieutenant governor, has adopted the standard "Not in My Back Yard" tactics used by citizen activists opposing polluting industries. Of course, most of those citizens fail in their efforts. But none of them chair the Senate Finance Committee. Ratliff does, which gives him a lot more influence in the process than your average Bill. The senator's fight with Pilgrim also brings into focus what has happened in Texas since George W. Bush became governor six years ago: The political power of interests that want to develop their land for industrial purposes has grown, at the expense of landowners who oppose the development projects. Indeed, opponents of the "confined animal feeding operations" -- giant, mechanized pig farms and feedlots -- operated by the corporate interests that dominate agriculture, have routinely been shut out of the legal process by the TNRCC and the Texas courts.

Although Ratliff brings a lot of power to his fight with Pilgrim, his rhetoric and his tactics are similar to those used by neighborhood and environmental activists. He has become an expert on Pilgrim's environmental record and has boxes of materials filled with documentation of Pilgrim's transgressions. Ratliff points out that during the past 15 years, Pilgrim's company has been cited numerous times by state and federal authorities for violating clean air and water laws. He says that Pilgrim's Pride has been fined a total of some $500,000 over that time period. Reaching into a box near his immaculately organized desk, the senator pulls out a TNRCC report that documents a 12-month period, beginning in January of 1998, when the company's wastewater plant exceeded its maximum permitted discharge into Cypress Creek on 215 days. Another page lists odor complaints registered by Mount Pleasant. A separate box contains records of fines for odor problems in the city.

"We are fearful that they will not do a good job of environmental controls," says Ratliff, who adds that he has talked to Pilgrim many times about the company's environmental violations. And he says the reason that he and other area residents, including Mount Pleasant Mayor Jerry Boatner, are fighting Pilgrim is simple: Pilgrim is "reaping what he sowed here for 30 years."

Strange Bird

Raising chickens made Bo Pilgrim famous. Handing out $10,000 checks inside the Texas Capitol made him notorious. In 1989, during consideration of a bill to reform the state's workers compensation laws, Pilgrim walked onto the floor of the Senate, where a committee meeting was concluding, and handed out $10,000 checks to key legislators involved in the workers' comp debate. Several legislators took the checks. When the story was reported in the news media, senators returned the checks to Pilgrim. (One senator didn't exactly return the check. He had already cashed it, so he had to write a new check to Pilgrim.)

As unseemly as it was, the public buying of influence was probably good for state government. It spawned a series of new campaign finance laws, including one that prohibits lawmakers from accepting campaign contributions while the Legislature is in session, or accepting contributions inside the Capitol. It also spawned one of Pilgrim's funniest lines. In 1991, while accepting the Bonehead of the Year award from the Bonehead Club of Dallas, Pilgrim said he had learned something from his misadventures in Austin. The lesson, he said, "may be summed up in a few simple words: automatic fund transfer." Using that method, he said, would have been better and faster and would have left no hard copies for reporters to see.

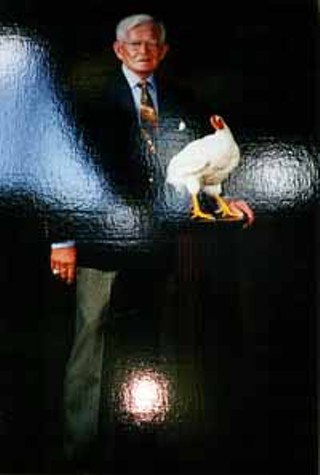

The story of Pilgrim's journey from a struggling country boy to Capitol Fat Cat and Chicken Magnate, is, by any measure, an amazing one. He was born on May 8, 1928, in a small house in Pine, a tiny community located a few miles south of Pittsburg, Texas (which itself is about 30 miles north of Longview). His father died when he was 11. "When I left home at 13, my mother had seven children and $80. So I knew that I had to depend upon the Lord." He moved in with his grandmother, who lived nearby. The home had no electricity or running water. The young entrepreneur had nine pigs, 100 pounds of grain, and no money. "I haven't asked a person for a penny since I left home at age 13," he says proudly. "And I promised the Lord if I ever amounted to anything, I'd recognize that in any public occasion that I have."

Since 1946, when he and his brother Aubrey opened a feed store in Pittsburg, Pilgrim has had many public occasions to testify. That feed store begat a feed mill, which begat a warehouse, which begat a small chicken business. That begat a big chicken business, which begat a chicken slaughterhouse. String together a few more begats, including a 1986 public offering which begat a listing on the New York Stock Exchange, and you end up in front of Pilgrim's state-of-the-art slaughterhouse on the northwestern edge of Mount Pleasant. It is reportedly the largest chicken processing plant in North America, handling some 2.25 million chickens a week. Within two hours it can turn a live, squawking chicken into packages of breasts, wings, and thighs.

It's clear that Pilgrim marches to the beat of a different drumstick. And his quirky mixture of Jesus, chickens, progress, and Horatio Alger has an undeniable appeal. It's also easily lampooned. Like John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd in The Blues Brothers, Pilgrim is convinced he is on a mission from God. That mission includes chickens. Lots and lots of chickens. Asked about that mission, Pilgrim cites the first book of Genesis, the section about God creating the fowl of the air. "He created these things to sustain man. I'm in a business that I'm proud to be part of the environment that the Lord created to support man.

"I think the Lord is using Pilgrim's Pride as an example of a Christian businessman," he said. "I believe that from the bottom of my heart. I know the Lord does that with me. He has tried me with fire and he has blessed me."

Even the most ardent atheist would have to agree that Pilgrim has been blessed. Chickens have made him very rich. He estimates his worth at "several hundred million dollars." He has a home in Dallas, a home on Lake Bob Sandlin, and a clutch of homes in Pittsburg. He owns the KingAir 300 that the company leases from him, and many of the company's largest chicken-raising operations, including its egg-laying operation, the Strube plants, are owned by Pilgrim individually. The company pays Pilgrim for the output of his farms.

From the tone of his response to a question, it's obvious that Pilgrim is tired of being asked about his company's environmental violations. He dismisses the charges that his company is careless when it comes to the environment. "We have a responsibility to the environment," he said. "I'm very sensitive to that. When you sin against the environment, you are sinning against the Lord." He adds that his company doesn't get enough credit for the good that it does, including its role in providing cheap meat and eggs for consumers. Pilgrim says that big companies like his have to "be practical," and that anyone who produces animal proteins, "like meat, milk, and eggs, we all from time to time have fines."

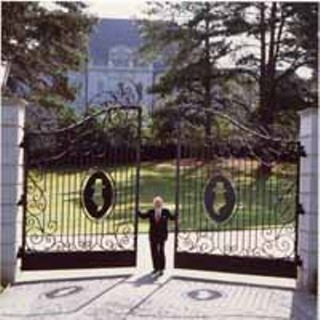

Pilgrim's family owns or controls 61% of all the stock of Pilgrim's Pride Corporation. And his fowl empire controls large chunks of Camp County. Records at the county Central Appraisal District contain 30 pages of computer printed listings of properties owned by Bo Pilgrim, Pilgrim's Pride Corporation, and other Pilgrim interests. In all, there are more than 400 parcels of land covering some 10,000 acres. But the showpiece is Pilgrim's mansion, a faux chateau that sits on the east side of Highway 271 on the southern edge of Pittsburg. Costing over $10 million to build, the 20,081-square-foot house contains eight bedrooms, nine bathrooms, an indoor swimming pool, and millions of dollars worth of French antiques, and is valued by Camp County appraisers at $4.2 million. Local residents call it "Cluckingham Palace." Bo calls it "my wife's house."

While Pilgrim lives large, he has shared his wealth with the citizens of Pittsburg and Mount Pleasant. Perhaps his most famous gift is the Prayer Tower, which sits on triangle-shaped Witness Park, near downtown Pittsburg. Completed in 1992, the 75-foot-tall stone spire contains beautiful stained glass, French bells, and Belgian clocks. Inside is a small chapel, chairs, a long kneeling bench, and a large, thumb-worn Bible on a lectern. There are no locks on the doors. Visitors come day and night to enjoy the quiet elegance and peacefulness of the place. Pilgrim also gives money to his church (the First Baptist Church of Pittsburg), to local schools, and to area charities. Yet there is still a lot of resentment toward Pilgrim, and the source of that resentment can be smelled by any visitor. In Pittsburg, it's the smell of the feed mill, which also happens to be the tallest structure in the county. The mill, which pumps out thousands of tons of chicken feed per day, gives off a smell, akin to warmed dog food, that can be detected for blocks around. In Mount Pleasant, the smell is often anything but pleasant. The slaughterhouse and rendering plant give off an odor of blood, fat, and baked bread that is at times overpowering.

But not everyone finds the odor offensive. Titus County Judge Danny Crooks is one of many elected officials who are loath to say anything negative about Pilgrim or his operation. The smell is "not as bad as it used to be," Crooks said carefully, adding that he is happy to have the jobs created by Pilgrim's company. Although Crooks wouldn't say if he supports the expansion of Pilgrim's operations in the region, he did try to put a positive spin on the odor problems at the Mount Pleasant plant. "When you smell that," he said, "it smells like money."

Citizen Senator

Much of what Pilgrim does doesn't pass Bill Ratliff's smell test. One of Ratliff's first jobs when he finished his engineering degree at UT 40 years ago was to work with the city of Mount Pleasant on problems they were having with their wastewater plant. Ratliff vividly remembers seeing the effects of the waste coming from the chicken slaughterhouse. "The [wastewater] plant itself was blood red," recalls Ratliff, adding that Pilgrim's operation was dumping large quantities of chicken blood into the sewer. The city's wastewater facility was choking on the blood, a substance Ratliff says is very difficult to treat. "And the city would fuss at Pilgrim and say, 'You've got to clean up this waste, we can't take that kind of waste.' And they'd say, 'We're gonna do better, we've got new equipment ordered, and we really promise this time.'" But the problems continued. For more than two decades, Ratliff says, the city of Mount Pleasant was routinely fined by the state for violating wastewater laws. After Ratliff's first experience with Pilgrim's waste, the city decided to build a separate water treatment plant and let Pilgrim's Pride run the plant that took waste from the slaughterhouse. And while that system has worked better, Ratliff says the company's plant routinely exceeds its permitted waste discharge. "So," says Ratliff as he leans back in his office chair, "I've dealt with their waste problems for 37 years."

Ratliff's civil engineering background has served him well, both in fighting Pilgrim and in balancing the state's books. Known for his ability to crunch numbers, Ratliff has been a leader in the Senate for several sessions. He is highly regarded by his Republican colleagues, Democrats usually find him fair, and Texas Monthly has named him one of its 10 best legislators in four of the past five sessions. Ratliff was elected to the Senate in 1988, becoming the first Republican to represent that region since Reconstruction. One of his most notable achievements was his effort in leading the 1995 rewrite of the state education code. Last session, he helped redesign the funding mechanism for state medical schools.

Ratliff, of course, doesn't have a perfect record. In 1997, he added a budget rider onto a bill that would have forced the state and its pension funds to sell nearly $800 million worth of stock in a half-dozen companies owning interests in record labels that publish rap music by artists like Snoop Doggy Dogg and Tupac Shakur. Promoted by conservative groups, Ratliff's bill was the first of its kind ever passed in the U.S. But it was so broadly stated -- prohibiting the state from investing in any companies that publish musical work which "describes, glamorizes or advocates" a long list of activities deemed objectionable by Christian conservatives -- that it might have stopped the state from investing in companies that publish music by outlaw composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, whose opera Don Giovanni is filled to overflowing with murder and mayhem. Fortunately, Ratliff's budget rider was ruled unconstitutional in April of 1998 by Travis County District Court Judge Scott McCown.

A native of Sonora in West Texas, Ratliff worked briefly as the city manager of Copperas Cove, before he began working full time as an engineer in Fort Worth. When his firm was bought out, Ratliff followed the job to Houston. In 1981, he and Sally, whom he had married in 1959, moved to Mount Pleasant to be closer to her family. Her father, Bob Sandlin, was a car dealer and community leader who helped convince state and federal officials of the need for a new reservoir in the region. His efforts led to the damming of Big Cypress Creek and the creation of the reservoir that now bears his name. For many years, the Sandlin family has owned the thickly wooded tract that sits just north of Pilgrim's land. Ratliff wants to make sure that the family can continue to use it as a vacation spot. "My personal concern is the degradation of the environment" near the Sandlins' property, Ratliff said. "My public concern is the degradation of the lifestyle here in Mount Pleasant."

Mount Pleasant mayor Jerry Boatner also worries about Pilgrim's environmental record. "Given the lack of stewardship that Pilgrim has shown, we'd be derelict if we didn't object to what Pilgrim is proposing," he said. Boatner acknowledges that he's probably costing himself money. The owner of a large furniture store located on the courthouse square in Mount Pleasant, he says the Walker Creek project would attract many more people to the area, and those people would need furniture. But if Pilgrim is allowed to double its production in the region, "we'd become a one-industry town. It would make us a company town."

There is already one company town in the region. In Pittsburg (pop. 4,446), the county seat of Camp County, when you are hungry, you go to Pilgrim's Place for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. When you need some cash, you go to one of the branches of Pilgrim Bank. When you want to pray, you go to the Prayer Tower. When you want to fertilize your lawn or plant a garden, you go to Pilgrim's Feed and Farm Supply. For snacks, you can stop at a local gas station, which sells ready-made Pilgrim's Pride chicken nuggets. That Pittsburg is Bo Pilgrim's town is even evident in the public pronouncements of its pro-Bo mayor. "Our prosperity in Pittsburg and Camp County wouldn't be what it is but for Pilgrim's Pride," says Mayor David Abernathy, as he sits in his cramped office in Pittsburg City Hall. Abernathy, a spry 88 years old and the second-longest-serving mayor in Texas, has held office for 51 years and followed Pilgrim's progress from a humble feed-store operator to chicken zillionaire. Pilgrim, the mayor says, doesn't get the credit he deserves. "He tries to help people that are in dire need. He does a lot of things for people that other people never hear about," said Abernathy. He added that the Walker Creek project will be good for Pittsburg. "It will mean a lot of income for the town and the county," he says.

Mount Pleasant, the Titus County seat, is larger, more prosperous, and has a broader economic base than Pittsburg. Pilgrim employs 4,000 people in Titus County, but Mount Pleasant alone has about 14,000 residents, so it has an identity separate from Bo Pilgrim.

But the company's dominance is still readily apparent. According to Ratliff, Pilgrim's workforce is primarily Hispanic, and those workers are placing a burden on the city's school system. He says about 40% of the elementary school students in the city speak English as a second language. And that fact "poses a serious problem" for the city's schools, he said.

Pilgrim's influence is not confined to the small towns of Titus and Camp Counties. Signs of his dominance are seen on every rural road in the region, where chicken houses are omnipresent. One tract of land a few miles east of Pittsburg has 24 chicken houses, all owned by Pilgrim's Pride and each containing 100,000 or more chickens. If the Walker Creek facility is permitted, the environment will have to accommodate even more chicken houses -- and the arsenic-laden chicken droppings (called litter) that come with them. That bothers Susan Nugent, a schoolteacher and activist who has been fighting Pilgrim for years. "Pilgrim doesn't know what the environment is. And because of that he doesn't care about it." Nugent sued Pilgrim a few years ago to recover the loss of some of her cattle, which were poisoned by excessive levels of arsenic after a flood washed chicken litter from Pilgrim's chicken houses onto her land. She says that Bo Pilgrim believes he is "a law into himself."

Pullet Together, Guys

Sometimes lobbyists really have to work for their paychecks. On August 23, Pam Giblin, a hotshot lawyer/lobbyist with Baker & Botts, who represents some of the biggest oil and petrochemical firms in the state, was working hard.

Along with Pilgrim and his entourage, Giblin crammed into an elevator at the TNRCC headquarters in far North Austin. Already in the elevator were Ratliff and his wife, Sally, who immediately began to squirm as she struggled to conceal her contempt for Pilgrim. She stood between her husband and Giblin, making sure not to look anywhere near the chicken king.

Giblin did all the talking, providing what little levity there was in a tense and crowded ride from the hearing chambers down to the lobby. All eyes were on the lighted numbers above the door as Giblin prattled on, assuring both Pilgrim and Ratliff that no damage had been done during the permit hearing and that perhaps the two men could still settle their differences. Giblin had plenty of reasons to keep both men happy: Pilgrim is her client and was paying her hundreds of dollars per hour. Ratliff is the chair of the Senate Finance Committee and could make Giblin's work in the lobby much more difficult if she did something to displease him.

When the elevator doors finally popped open, Giblin said to the two opponents, "Okay, you two, at least smile at each other." Pilgrim and Ratliff warily did as instructed, exchanged short pleasantries, then parted.

Giblin and Ratliff had just squared off in front of the three TNRCC commissioners in a hearing on Pilgrim's injection-well permit for the Walker Creek project. Ratliff, along with another Camp County landowner, Joseph Ashmore, a Dallas-based lawyer, had objected to an aspect of Pilgrim's permit application. They argued that the application was faulty and the commission should force the company to reapply, because it had not included certain holding ponds and other wastewater equipment in the permit application. Giblin argued that the application was complete as submitted and that the commissioners should expedite its approval. In the end, the three commissioners, who were clearly uncomfortable dealing with the man who helps decide their agency's budget, split the chicken and decided that Pilgrim's Pride will have to make a minor amendment to its application and then resubmit it, effectively delaying a showdown on the topic.

This fight between Pilgrim and Ratliff could wind up being good for the Texas environment. Ratliff points out that current law allows the TNRCC to examine the past compliance record of companies when considering new permits. The senator says he believes that the wording in the law should be changed to say that the agency shall examine compliance histories before granting any new permits. He attempted to make that change in the TNRCC permitting regulations last session. And he has hinted that he will introduce a bill in the coming session to change the wording in the statute.

It's not clear yet whether Ratliff will prevail in his fight with Pilgrim. But his position in the Senate is certainly helping him get the permit fight delayed. The TNRCC recently ruled that it will not be able to take up the permit again until next June. That's because Ratliff will be working as a legislator from January through the end of May. That delay infuriates Pilgrim, who insists that Ratliff is abusing the power of his office. Even more inflammatory is Pilgrim's charge that Ratliff is opposing Pilgrim's expansion because he doesn't want any more Hispanic workers to move into the area. "His problem is that he's racist and he's jealous of what I've built," said Pilgrim during a recent phone interview. When asked if he was sure he wanted to use the race charge, Pilgrim quickly replied, "I just said it." Shortly after that, Pilgrim added that he has "tried to take the high ground with Ratliff and let him self-destruct. And he's to that point."

Ratliff sneers when told of Pilgrim's racism charge. "I can't imagine anything more racist than having an operation that has spewed nauseating odors into the major minority housing area in Mount Pleasant for 30 years," he said. Then, lapsing into his cool, engineering mode, Ratliff says he will focus his fire on the science behind Pilgrim's injection-well plan. He says chicken waste has never been injected into the ground before, and that tests done on the wells didn't use the same type of greasy, particulate-laden wastewater that will come from the slaughterhouse at Walker Creek. "I think what they are planning is experimental," said Ratliff. "The burden is on them to show that it will work. And they have not shown that."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.