Justice Delayed?

The Governor's Response to a Federal Judge's Decision Angers Two Democratic Legislators

By Louis Dubose, Fri., Sept. 22, 2000

On the last day of August, Governor George W. Bush was caught off guard at a Cincinnati airport. From reporters, he learned that federal Judge William Wayne Justice had ruled that the state of Texas is out of compliance with a federal mandate to improve its delivery of Medicaid services -- the federal-/state-funded medical and dental program for the poor. Bush tried to stay "on message," but reporters wanted a response. He would have to study the judge's ruling, Bush said. Campaign communications director Karen Hughes had a more specific response. "The state very much disagrees with the findings of this very liberal federal judge," Hughes told reporters. The state, she said, would appeal.

Since then, Bush spokesperson Linda Edwards has defended the state's recent record on Medicaid, saying "we strongly disagree with the opinions of Judge Justice, because Texas has made tremendous strides in helping poor children access preventative health care." Republican Attorney General John Cornyn has begun the process of appealing the judge's decision, and on Monday, a spokesperson for Cornyn said the AG is considering requesting a stay of the judge's order compelling the state to act by October 13. Cornyn said the state has increased medical spending to $140 million last year, up from $87 million in 1993 when the lawsuit was filed. Transportation expenses, he said, also increased from $19 million in 1993 to $39 million in 1999. And 66% of eligible patients last year applied for medical checkups, compared to 29% six years ago when the suit was filed.

Yet "the state" that Hughes referred to in her response to reporters is not exactly acting in concert. After Cornyn announced his intent to appeal, 20 Democratic legislators, most from urban areas where medical needs of poor children are most acute, held a press conference in Austin. They urged the governor to comply with the ruling, in which Judge Justice wrote that the state's Medicaid outreach program fails to inform parents that their children are eligible for Medicaid; that the state has failed to inform Medicaid recipients of the free transportation system available to get children to doctors' or dentists' offices, and that outreach efforts "do not generate particularly high levels of participation among eligible recipients." Justice also wrote that the failure of Medicaid in Texas is most evident in children "suffering from acute forms of dental disease that, while easily preventable, often lead to such health complications as serious oral infections, dehydration, fever, and malnourishment stemming from the inability to eat."

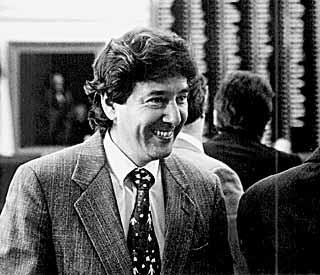

Among the most vocal critics of the governor's response to the Medicaid lawsuit is Rep. Elliott Naishtat (D-Austin), who chairs the House committee that handles most legislation relating to Medicaid. "Everyone who has studied the issue knows that Texas has problems delivering adequate and appropriate Medicaid services to children," Naishtat said. "To appeal this decision instead of putting all our time, resources, and money into addressing the problem outlined by William Wayne Justice is an example of putting a higher priority on saving face than on doing the right thing. We're talking about the health care needs of over one million children in Texas."

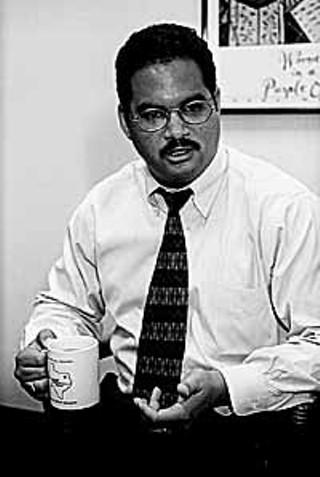

Rep. Garnet Coleman, a Houston Democrat who is known as something of a social services wonk, also challenged the response of the governor and the attorney general to Justice's ruling. Reached in Washington, D.C., Coleman took a position similar to Naishtat's. "It makes no sense," he said of Cornyn's appeal. He noted that Harris County last year paid out $10 million to provide medical services for the same class of children represented in the lawsuit. "With Medicaid, there's a third party paying, through a 60-40% federal split. We send our tax dollars to Washington, and this is one way to get them back." In other words, through Medicaid, the federal government covers more than half the expense of treating indigent children who often show up in emergency rooms, where their bills are passed on to counties.

Naishtat and Coleman also made similar arguments about Governor Bush's aversion to Medicaid. Both legislators -- who five years ago collaborated in a successful effort to block the governor in his attempt to turn the administration of welfare services over to private companies such as EDS and Lockheed Martin -- pointed to specific legislative fights they say demonstrate the governor's hostility to Medicaid. While the two Democratic legislators aren't exactly arguing that Governor Bush recuse himself from the Medicaid lawsuit, they do suggest that he has a strong bias against the program -- and that poor children and the state would benefit if the state would comply with Judge Justice's ruling.

Many of the children currently being enrolled in the Medicaid program have nothing to do with the aggressive outreach Judge Justice ordered in 1996, Naishtat said. They are children who were dropped from Medicaid rolls as an "unintended consequence" of welfare reform. In Texas, almost all Medicaid clients are children of parents who qualify for public-assistance programs. "They're means-tested," Naishtat said, and those who have too much income don't qualify. As welfare programs for adults were eliminated, children began to fall off the map. And that wasn't necessary. "Many of the moms assume that because they lost their benefits [under welfare reform], their kids are no longer eligible," Naishtat said. "We had tens of thousands of kids in Texas losing Medicaid because their moms didn't know that when they went off welfare, the kids were still eligible."

To address that problem, Naishtat last year filed a bill that would require the Dept. of Human Services to review the eligibility of children losing Medicaid coverage. "They fought us tooth and nail," Naishtat said of Bush and his staff. Naishtat first included the protection for children in an omnibus welfare reform bill that ultimately died in committee because the governor and Democratic legislators could not agree on several critical issues. "While we were still on track to get welfare reform last session," Naishtat said, "Terral Smith [Bush's legislative director] came to me and said we would never come to a meeting of minds unless I pulled the language that directed the Department of Human Services to review the kids' eligibility."

In response, Naishtat removed the provision from the welfare reform package and filed it as a separate piece of legislation.

Naishtat says he was blindsided by the quietly organized opposition to the bill when it came to the House floor. "There was almost no debate, maybe five minutes," Naishtat said. "I was shocked to look up and see that it barely passed on almost straight partisan lines. It was so close that they [the Republicans] called for a verification. So it was obvious that the governor had put the word out on this bill. It was so important to the governor.

"Smith was asking how can we afford to re-enroll those kids in Medicaid," Naishtat said. "But we were already paying for those kids before their moms went off welfare and assumed the kids were no longer eligible." The bill also passed in the Senate, but Naishtat's original language that made review of children's eligibility mandatory was replaced by a provision that says the Dept. of Human Services may review eligibility. Nonetheless, some of the increased Medicaid spending the attorney general is citing to defend the state's performance is a result of the DHS bringing children back into the program, Naishtat said.

Coleman cited a 1995 Medicaid-related health care initiative that he says would have made as many as 570,000 poor children eligible for health coverage -- if the governor had aggressively pursued a federal waiver that would have eased income requirements for Medicaid recipients. First reported by Clay Robison in The Houston Chronicle last week, the account of Bush's role in the failed 1995 health initiative -- which would also have provided prescription drugs to 255,000 of the state's poorest adults -- drew an angry response from the governor's press office. "The federal government's insistence to dictate from Washington with bureaucrats and mandates instead of letting Texas decide how best to expand health care coverage resulted in the people going without health care coverage," said Bush spokesperson Edwards. But Coleman, who drafted the proposal and was involved in discussions with the governor's office five years ago, disagreed. In a telephone interview last week he said the Medicaid waiver the state requested in 1995 never was denied -- it was allowed to die.

The request would have expanded Medicaid to include families with incomes as high as 133% of the federal poverty level (approximately $21,000 a year for a family of four) and would have also covered individual adults who earn less than $3,360. In Texas, Medicaid currently only covers children and disabled or elderly adults. When the federal Health Care Financing Administration returned the state's waiver request because the state had failed to list any health care providers other than county hospital authorities, Bush's office allowed the request to die. Says Coleman: "They [the federal agency] never denied the request. The negotiation was never completed, and the proposal was never approved."

To Coleman, the reason the proposal to expand Medicaid died is evident. "It died because the governor never would put his back into it," Coleman said. "That's why it died."

"These are very vulnerable populations we're talking about," Coleman said. "You don't want children to be sick. That's a good policy goal: not to have sick children, not to have disease when it can be prevented." It's also sound fiscal policy. When the parents of poor children can't afford doctors' visits, Coleman explained, the kids often end up in emergency rooms with acute health problems that could have been prevented if the children had access to a physician. The state, he argues, should take full advantage of the federal funding provided through Medicaid, so that the counties and the state aren't left picking up the indigent care bills for children who qualify for Medicaid.

Bush's position on the Medicaid lawsuit seems to have jump-started the legislative process, with Naishtat, Coleman, and other urban legislators promising to work on Medicaid eligibility and delivery of services in the next session. One House subcommittee will meet Sept. 21, to consider Judge Justice's decision. And the Human Services Committee that Naishtat chairs is again addressing the Medicaid issue. "The governor says we should leave no child behind, but what about all the hundreds of thousands that would have been covered by [Coleman's] bill in 1995, and my bill last year?" Naishtat asked.

"We will take this matter up in the Legislature next year regardless of what the attorney general does," Coleman said. "And the merits of this case are on our side." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.