Meow Mix

Texans Are Wild About Exotic Cats, but at What Cost?

By Cheryl Smith, Fri., Aug. 4, 2000

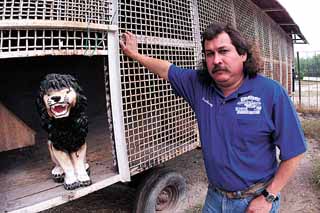

When David Ramirez brought Simba home, it never occurred to him that the fuzzy 20-pound lion cub would measure nine feet long, weigh about 300 pounds, devour three packages of chicken a day, and die a gruesome, undignified death, all before its fourth birthday. Simba lived in a 10-by-22-foot cage behind Ramirez's business, a country-western tourist shop a few dirt yards from the Rio Grande River and the hand-pulled Los Ebanos Ferry. Ramirez is quick to point out that life hadn't always been that way for Simba, who he purchased for $1,200 from a now-deceased exotic cat breeder in nearby Edinburg. "He used to love to run around the house," Ramirez says. "When they're babies, they're really cute, but when they get bigger, they start messing up the house and you have to build them a big cage and all." Even if Ramirez, a chatty man with a mane of curly black hair and a short bushy mustache, has brighter memories of Simba's youthful days than of the ones the cat spent locked up, he says he never doubts his decision to purchase the African lion. "I don't regret buying that lion," says Ramirez, who has a plastic yellow "lion crossing" sign on display near his store's front door. "He was my pet." Private ownership of big cats is becoming increasingly common in Texas, where there are no statewide regulations of exotic animals. It's difficult to say how many lions and other big cats call Texas home, because the state keeps no statistics. Brian Werner, director of the Tiger Missing Link Foundation, a Tyler-based nonprofit organization, tracks tigers for genetic research purposes. He says his data indicate around 2,200 tigers in Texas alone. And according to the Tiger Information Center, a joint project sponsored by the Save the Tiger Fund, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Exxon, and the Minnesota Zoo, there are fewer than 8,000 tigers in the world.

Carol Asvestas, director of the Wild Animal Orphanage in San Antonio, hears stories like Simba's all the time. She says she gets about eight calls a month concerning taking in a big cat, compared to only two or three before 1997 -- the year the Texas Legislature transferred responsibility for monitoring exotic animal ownership from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept. to individual cities and counties. "We've always got a lot of big cats. Everyone's filling up, and I believe the problem is getting steadily worse," says Asvestas, whose four-acre animal compound is home to 21 cougars, 18 tigers, five bobcats, four panthers, four leopards, three jaguars, and two lions.

Cindy Carroccio, co-owner and director of the Austin Zoo, a sanctuary/zoo in Southwestern Travis County, tells the same story. Her 13-acre facility houses three tigers, three lions, three cougars, two leopards, four bobcats, and three servals, among more than 100 other exotic and domestic refugees. "Right now the leopards are bunking with the cougars until the permanent leopard place gets built," Carroccio says. "Everybody's maxed."

The National Alternative Pet Association, which according to its online mission statement (www.altpet.net) promotes the responsible private and commercial ownership of exotic animals, has a Burnet, Texas, mailing address. Program manager Jazmyn Concolor says she doesn't know how many members NAPA has, but estimated that its Web site gets about 2,000 hits a month, largely from people seeking their first exotic pet or information on how to care for one. "Mostly, NAPA was created to help support the owners of exotic animals with a wealth of information on exotic animal husbandry, so that the animals might benefit from the knowledge," Concolor says.

NAPA member Mary Robbins, who keeps 15 exotic animals at her home near Lago Vista, says the group's main premise is that alternative pet ownership is a right, as well as a responsibility. "We think that most people do not have a [suitable] lifestyle and are not equipped to have these animals, but we do not think it should be illegal to have these animals," she says. "Tigers should not be backyard pets in suburbia, but it's a case of rights vs. responsibility. We don't believe in removing rights from people."

NAPA is one of several Web-based exotic animal groups with an e-mail listserve. Members of these electronic lists flood each other's mailboxes with messages that touch on everything from coffee-drinking tigers and potty-trained bobcats to state legislation and municipal ordinances that could restrict exotic animal ownership.

Robbins, who started keeping exotic animals as pets during her days as an animal hospital manager in the Seventies, has her own animal Web site, dedicated largely to Alagahi, a sanctuary/mini-wildlife park in the making. She describes her idea, which includes giving tours and birthday parties among the animals on her property, as a personal indulgence, as well as her retirement plan.

"They've brought so much joy into my life. I just want to share them with other people," she says. The "Visit Alagahi" page of her Web site (www.alagahi.com) features a photo of a cougar cub lying on shiny, black tiles in front of a fireplace in her living room. Visitors must schedule appointments and pay a few dollars before they can see her menagerie, which includes one cougar and one bobcat. "Those who want individual contact with the exotic animals (with a trainer) and have his or her picture made with them, there is a $10 separate charge per person," the page explains.

Regulatory Shortcomings

Even when Texas Parks and Wildlife regulated the state's exotic animal industry, the agency barely had sufficient resources and manpower to do its job effectively, says L.D. Turner, TPWD's lieutenant commander game warden, who ran the agency's exotic animal regulation program from 1996 until it disbanded in 1997. And the way things are now, he adds, "We don't even have a warden in every county of the state."

Turner does not believe the parks department should be responsible for regulating the state's exotic feline industry. "This industry is a public safety matter, not a wildlife matter," he says.

Under current laws, owners must purchase a license from the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture's Animal Care Office in Fort Worth if they intend to breed, buy, sell, or exhibit an exotic animal in Texas. An official from the department inspects the applicant's property before approving a license. But individual, noncommercial owners are only required to have a license if their county or city requires one.

"I could go to Wal-Mart with a bunch of tigers in a box, put 'Tigers for Sale' on it, and sell them to anybody," says Rick Watson, executive director and co-owner of Noah's Land Wildlife Park in Caldwell County. (See Tiger, Tigerin this issue.) "It's legal to sell them to whoever." Watson is against having exotic cats as pets, but he has 41 tigers at his 400-acre drive-through wildlife park/sanctuary/motor home campground. A director at British Aerospace Systems in Austin, Watson developed an interest in raising tigers about six years ago. That was when his wife Cheri, a licensed wildlife rehabilitator, brought home a two-day-old tiger that had been accidentally crushed by its mother. "It just snowballed from there," says Watson, sitting in a chair shaded by the park office's covered front porch. He and Cheri breed their tigers but have never sold any to individuals -- only zoos, he says.

Exotic animal breeding is a controversial issue, especially among sanctuary and refugee owners, who are often vehemently opposed to big cats being born into captivity. But about 20 cubs have been born to tigers bred at Noah's Land since Watson purchased it a little more than two years ago, he says. The Watsons say their breeding is justified because at least one of their tigers carries a very rare white tiger gene. "We're not in the tiger baby and tiger-selling business," Cheri says. She noted, however, that if "the perfect person" with the proper facilities came along, they might entertain selling them a cub. The Watsons have a two-week-old white tiger, bred at Noah's Land, on display in the park's nursery room. Seven orange, bottle-fed cubs occupied the room's three cribs a few weeks ago. Both Watsons said that batch didn't come from Noah's Land, but from three adopted tigers that came to them pregnant and gave birth almost at the same time.

The park, which has been around for 13 years, has gone through several changes of ownership and was even auctioned off animal by animal a few years ago. But it recently received government approval as a nonprofit organization. The USDA officially denounced the ownership of exotic cats as pets earlier this year, but the agency doesn't have much regulatory muscle to enforce its position.

"We don't license the actual animals. We only license these commercial activities," says Charlie Currer, one of three USDA animal care inspectors in Texas. Currer spends most of his time on highways and byways that stretch from Texarkana to Brownsville; he is responsible for checking about 200 commercial exotic animal sites. And he tries not to take what he sees in his rounds personally. "How I personally feel doesn't really enter into what I do because I can only do what the law says," says Currer of his job.

Texas Is No. 1 for Attacks

Texas leads the nation in exotic feline-related injury and death cases, says Dena Jones, program director with the Animal Protection Institute, a Sacramento-based animal rights group opposed to the private ownership of nondomestic animals. API has pieced together a partial list of attacks on humans by captive felines. According to the list, which is heavily based on incidents covered by the media, 10 out of the 26 reported attacks in the past three years took place in Texas. The state generally comes out with high numbers in incident-based reports because of its large size and population. But the institute's data shows that in California, the country's most populous state, there has only been one reported attack over the past two years. Jones attributed the low number to tightened statewide exotic animal regulation.

The most recent incident involving a captive feline in Texas occurred in March, when a tiger near Houston in Harris County tore off a four-year-old's arm. Jayton Tidwell, who lives in Arkansas but was visiting family in Texas, apparently stuck his hand into the chain-link-fenced cage of his uncle's pet tiger. The cat, which lives in the uncle's back yard and is reported to have always been a calm animal, severed the child's arm just above the elbow.

But Brian Werner says the chance of getting injured by an exotic cat in captivity is slim, and that the small number of incidents that have occurred have been sensationalized out of proportion. "You have a better chance of being hit at your mailbox by the mail truck than getting bit by a cat," he says. Werner's example puts the work of his fellow exotic feline lover, George Stower, into layman's terms. Stower -- who doubles as vice president of the Long Island Ocelot Club Endangered Species Conservation Federation and as a nuclear safety engineer in upstate New York -- analyzed data from a survey conducted by the federation, whose members support private ownership of wild cats. Comparing the results of the survey against the risk factors of other activities, Stower concludes that the likelihood of a member of the general public needing professional care for a big-cat injury is less than a tenth of a percent per cat-year, compared to National Highway Traffic Safety Administration statistics that say the probability of an individual being injured by an automobile -- not counting the vehicle's driver or passenger -- is almost 2% per vehicle-year.

Time to Take Control?

Still, it stands to reason that Texas could see fewer exotic feline-related injuries and deaths if the state would regulate what has become a booming, laissez faire industry in the state. On a national scale, says Jones of the Animal Protection Institute, Texas and North Carolina are the only two states lacking a statewide law regarding exotic animal ownership and leaving regulation completely up to individual counties and municipalities. Some Texas municipalities, such as Austin, San Antonio, Houston, and Fort Worth, have ordinances that prohibit individuals from keeping potentially dangerous animals inside city limits. Few counties, however, have such ordinances. (See "Local Ordinances," p.36, for a partial list of how regulations vary statewide.) Travis County does not restrict exotic animal ownership. In fact, two out of the three tigers at the Austin Zoo, Raj and Kali, were originally found wandering just outside of the city limits around Lake Travis, says co-owner Carroccio.

Animal rights groups are pushing for bans on exotic animal ownership in the private sector. As API's Jones puts it, "strict regulation is the next best thing to abolishing the pet trade."

Animal sanctuary and refuge owners have a problem with this philosophy. "They try to say that nobody should have these animals. In a perfect world, we shouldn't have them, but this is a problem we inherited from our forefathers. They're our responsibility," says Werner, who runs the Tiger Creek Wildlife Refuge outside of Tyler. Though he wants national exotic feline regulation and opposes the idea of big cats as pets, Werner, like many involved with the rescue and rehabilitation of big cats, says that banning private ownership outright would shut down the country's sanctuaries and refuges, most of which are privately owned."We have to keep things in perspective," he says. "We don't need something that's going to cause thousands of people to all of a sudden become criminals." Werner says lawmakers and regulators need to differentiate among pet owners, sanctuaries, and refuges, as well as private zoos and circuses. Echoing those sentiments is Marsha, who runs a small USDA-licensed exotic feline refuge on her Southeast Texas property, and declines to give her last name for fear of becoming a complaint target for animal rights groups. " I don't like the thought of being clumped in with the people I try to rescue them from," says Marsha of her refuge's 10 cats, all of which were all saved from bad situations, she says."The people that know us respect us for what we are doing," she says.

Asvestas, the Wild Animal Orphanage owner, says anybody with an exotic animal should have to be USDA-licensed and undergo routine inspections, whether their ownership is commercial or not. "Inspections are good because they keep you on your toes," says Asvestas, who has had problems at her facility, including a break-in resulting in the intruder getting a finger bitten off by a tiger, and another incident in which a tiger escaped from its enclosure. "Somebody like us, that follows all the USDA procedures, if we're vulnerable to break-ins and escapes, think about the ones that aren't regulated. There has to be a lot of stuff that goes on behind closed doors that doesn't get reported," she says. "We've gone through so much hell with USDA, but I would rather be regulated than not be regulated. I don't think it hurts to have somebody from the outside schooling you."

Simba's Last Roar

Some counties apparently aren't aware that the parks department no longer regulates exotic animals. That is the case in the Valley's Hidalgo County, where Ramirez raised his lion, Simba, until it died last December. "As far as we're concerned, we don't monitor those things," says Roy Tijerina, chief environmental health inspector for Hidalgo County. James Dawson, a justice of the peace in DeWitt County, presided over an inquest into the death of a local girl killed by a tiger last summer. The incident prompted several discussions and disagreements among county officials about banning exotic feline ownership, but never led to any action, he said. "People in Texas are funny that way," says Dawson. "They don't like a lot of regulation. They like their freedom."

Ramirez bought Simba at four months as a present for his then-17-year-old son. Simba slept in bed with Ramirez's two boys for his first few months with the family. Ramirez's voice shifts from amiable to grim when he recounts the day Simba lost his indoor-kitty status."When he was about seven months old, he tore up a very luxurious sofa and a stereo system, and my wife said, 'You get that animal out of the house,'" he says. Ramirez built Simba a cage out of an old cotton trailer. He put it in his back yard, where the increasingly noisy baby resided until becoming an unpopular neighbor. "You could hear him for a good half-mile away. On a still night, you could hear him even further away, even way back into the woods," says Javier Ramirez, David's cousin and a neighbor in Peñitas, a quiet, rural town of about 1,800.

It was legal for Ramirez to have Simba in Peñitas, but he decided to move the lion to nearby Los Ebanos, a dusty Rio Grande community of a few hundred people, where Ramirez's store, the Los Ebanos Ferry Junction, is one of few signs of life. With Mexico's tiny border community of Diaz Ordaz being Simba's closest neighbor, his bellowing roars stirred up little more than dust, says David Garza, another cousin of Ramirez, who sometimes lives in the apartment tacked onto the back of the store, and who helped take care of Simba."I tell my friend that when he roars, even the trees shake," said Garza, a couple of months before the lion was supposedly killed.

Ramirez, who was USDA-licensed to exhibit Simba, says he had planned on taking care of his pet for as long as he could. But if for some reason he couldn't handle his lion any more, he would have tried to get a sanctuary to take it. Simba spent a large part of his time lying on the cement bottom of his boxcar-shaped home, the pads of his giant front paws pressed against the white, semi-rusty metal bars that run from the cage's raised bottom up about six feet to a black, shingled roof. The lion's cage sits on wheels, like a circus car, except the tires are too low to roll. Ramirez points to the wooden-planked floor of the now-empty cage. "The trailer was completely covered in blood. It was dripping through the cracks on to the ground," says Ramirez, describing what one of his store employees found when he went to feed Simba the morning of Dec. 5.

Simba was vomiting blood, and continued to do so for the rest of the day, says Ramirez, who rushed over to Los Ebanos from his home in Peñitas as soon as he was notified. Ramirez called Simba's veterinarian, Dr. James Baker of Edinburg, whose interaction with the lion had thus far been limited to inspecting the animal from afar; just enough for Ramirez to get his USDA exhibitor's permit. Baker, who has been a vet for 50 years, says there was nothing he could do for Simba because he's not an exotic animal specialist. "There is no way I could treat his lion because I couldn't get to it," says the 73-year-old. "I can't just go in and work on a lion like that." The only exotic animal specialists in the Valley work for the Gladys Porter Zoo in Brownsville, Baker notes.

Ramirez, who says he found footprints on the ground behind Simba's cage the day he died, has concluded that the lion was poisoned. He didn't have an autopsy performed because it would have been too expensive, he says. If Simba was poisoned, it wasn't Ramirez's first time to lose a pet in that fashion. About three years ago, when Ramirez was keeping Simba in a cage in his 20-acre back yard in Peñitas, the lion was the lone survivor of a mass murder, in which 16 dogs, five goats, and four bobcats, all of which Ramirez kept as pets, were poisoned."One day I just woke up and they were all dead. I cried like a baby," recalled Ramirez in an interview a couple of months before Simba died.

"The lion was the only one. They were afraid to get close to him, I guess."

The Valley's unforgiving sun beats down during the short walk from the empty cage to Ramirez's store. It's the same sun that scorched the earth around the boxcar, leaving the lion inside panting under the weight of a thick, golden mane. " I sometimes get a little sad looking at him," said Garza of his cousin's lion before it died. "When he roars, I feel that he's probably lonely. I think maybe he needs a girlfriend." Garza was attached to Simba because he often fed him his daily meal of store-bought chicken.

Ramirez skinned his dead pet himself, crying all the while, he says. He had Simba's decapitated body cremated. The head, which he stores in the same freezer the animal's uneaten packages of chicken are kept in, is going to a taxidermist to get stuffed, he says. Ramirez has no intention of giving up on trying to raise exotic animals as pets. "I'm going to get me another animal. I'd like to get some kind of deer from Africa, or maybe a tiger or a panther," he says. "I haven't decided." ![]()

For a photo tour of Noah's Land Wildlife Park, see Tiger, Tiger.

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.