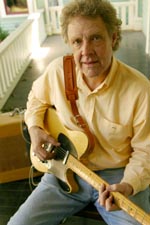

Space Cowboy Steve Miller's Not Joking

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame guitarist details the pompitous of musical education

By Raoul Hernandez, Fri., July 22, 2016

Steve Miller's diamond career arcs from the postwar blues of the Fifties to his induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in April.

The 72-year-old guitarist bookended a buoyant two-hour interview with a 40-minute deconstruction of the latter "institution" – initial comment since his merciless criticism back in the spring set off a firestorm of headlines – and an equally extensive oral history of collaborating with album art visionary Storm Thorgerson on 2010's Bingo! (coming to the Chronicle July 29). In between, the Dallas-reared bluesman detailed instrumental apprenticeship at the hands of Les Paul and T-Bone Walker, covering a trio of Jimmie Vaughan tunes on Bingo! ("My wife and I are doing nine shows in the next three years at Jazz at Lincoln Center about blues and Jimmie's the first artist I invited"), and going viral.

To the following pressure points, Miller was also quick to reveal a unique convergence on his current tour.

"For the show in Austin, we've invited [harmonica great] James Cotton to perform. I used to see him all the time in Chicago. We did 100 shows together, recorded together lots, and became really good friends. So we're going to honor him, and we invited some other local guitar players [coughs, then laughs]."

Rock & Roll Hall of Fame

Austin Chronicle: Far less shocking than what you said about the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame was the fact that more musicians haven't spoken up similarly.

Steve Miller: I agree [laughs]. Everybody I've met or seen, 100 percent has said the same thing. That goes from Elton John to people you don't know [laughs], the whole spectrum. Everybody said, "It's such a mess. That Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is such bullshit." The thing that amazed me was how great the television show looked. Stunning. I look like I had the best time of my life when it was one of the stalest, most boring evenings ever.

I mean there was no Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. We never were introduced to each other. There should've been a dinner so that everyone could meet: the inductees, the people who were going to induct us, the people from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. They should've explained to the people being inducted what it is, what its educational programs are, how you as a new inductee can help us raise money for music education.

Instead, it was like the soundcheck: "We're making a television show, hurry up or we'll cut you from the show. Do this, or we're gonna cut you from the show. You have no control over anything, or we're gonna cut you from the show. We own all elements of the video you give us, or we're gonna cut you from the show."

And at every level we're going, "Fuck you, cut us from the show. Go ahead. Great. Have a great fucking show." You know? "Good luck."

They played everybody against everybody. I didn't sign my deal until they had given me everything I wanted, so now I'm not allowed to talk about it [laughs]. That was the most anti-musician document I've seen probably in my life, and that goes back to the Sixties when it was like [affecting an East Coast accent], "Hey kid, you wanna make a rekkid?"

You know, like from the Chuck Berry days, where if you sold a million records, they gave you a $3,000 Cadillac and no accounting [laughs].

I don't think they started out that bad, but it became such an important thing to the people running it to have say over everything. I had guys call me up who were on the nominating committee that said, "You know, I quit after two years, because it seemed like some people would go into a back room and come out and tell us who was going to be nominated." And you get outside the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and people all over the world have heartfelt feelings about who should be in it. About artists.

It's supposed to be an important rallying point for live music – for recorded music, for artists, for artists' rights, for music education. They're supposed to be the world headquarters for music education, and intellectual property rights, and musicians' health concerns, and all the things musicians really need but don't have. They're none of that. It's just a private boy's club.

My current tour, the first gig was in Cleveland a couple of weeks ago. We went right over to the Hall of Fame and I saw the music programs. There were some kids playing at the Hall of Fame, but no one watching them. They were playing on the plaza when I arrived. There was no one there. And they were great! When they stopped playing, I went up and said, "Hi, I'm Steve Miller and I just want to talk to you for a minute. How are you guys doing?" And they were all real excited, of course, because they were playing at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

AC: Rock & roll's universal, but the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame is exclusive, so why do its biggest practitioners even care about getting in?

SM: Well, because we all love the originators of rock & roll. I mean, I backed up Chuck Berry 20 times. I know Chuck Berry [laughs]. Musicians understand where it all comes from. Forget about all the politics. It's the other side of it: "Wow, I'm in a group with Les Paul, T-Bone Walker, Fats Domino, Bo Diddley, Miles Davis." It's a long list. And I'm not going to sit there and say, "Hey, N.W.A. does not belong in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, and neither do the Steve Miller Band, because they're nowhere near as important as Bob Dylan or Mick Jagger."

What needs to happen is it boils down to this: Jann Wenner and Allen Grubman and Ahmet Ertegun and a couple of other lawyers and record executives had the combination of a good idea, a tax write-off, a control grab – all of those things. Those people were very sophisticated and very smart. The only city that would even talk to them was Cleveland, so they put it there. They were very practical. They got a beautiful museum made. It's the I.M. Pei building, an absolutely beautiful, modern, unusual structure. It's a work of art itself.

But then they set it up in a manner where Jann controls everything, which was great for him. He's like the Louella Parsons of rock: He makes careers, he breaks careers. He's smart, he's good, he's bad, he's stupid, he lies, he cheats. He's a human! It's just time to take it away from those people. They need to leave. Because they started something the world really cares about.

So in spite of all this bullshit that I went through with these guys, I'm really glad I'm in [laughs]. I'm glad I'm in this group that people really care about.

T-Bone Walker

AC: You mentioned blues great T-Bone Walker, and I was shocked to learn he was a friend of your family's when you were growing up in Dallas.

SM: T-Bone was a sweetheart, number one. The first time I ever saw him was about 5pm in Dallas. He drove into our driveway in a flesh-colored Cadillac convertible with real leopard skin seats. I was 9. He stepped out of the car, in a suit with a tie on, carrying a big guitar case. He came into the house and I i-m-m-e-d-i-a-t-e-l-y asked if I could see his guitar. He opened it up, showed it to me, and started playing. He taught me how to play the guitar behind my head and how to do the splits.

T-Bone played a bunch of parties at our house, so I learned to play lead guitar sitting two feet away for six hours at a time. He'd arrive at 5pm, we'd have dinner, and then the party started. They'd play 'til 5am. I just was like a fly on the wall. He was sweet, patient, and just a lovely man.

AC: What was his friendship with your parents based on?

SM: This was Dallas, 1951. It was completely segregated. When I was 5, we came to Texas from Wisconsin, where we had lots of musician friends. Les Paul was my godfather. He was around the house when I was 4, 5, 6 years old. Charles Mingus used to come over. Red Norvo, Tal Farlow – people like that – were at our house at parties. My dad was kind of a hipster, and a doctor. We lived just down the street from a really cool club in Milwaukee that was a secondary place for everyone that played in Chicago.

So then we moved to Texas, and what the fuck? Everything was segregated. What's going on? What's a yankee? What's a rebel? A lot of our neighbors thought we were communists. My father ran a pathology laboratory and he employed black lab technicians. A couple of his lab technicians actually went on to go to medical school and became pathologists – female pathologists. Female, black, pathologists [laughs]. I'm very proud of my dad.

But to give you an idea of what it was like, he was arrested, handcuffed, had his picture taken and posted on the front page of the fucking Dallas Morning News for having a "race party" at his laboratory at 3pm before the Christmas break. I think it was [state U.S. Senator] Ralph Yarborough who finally got the Morning News to print a retraction, but they made him sound like he was some sort of swanky abortion doctor. My old man went right downtown and told everybody to fuck themselves when that happened [laughs].

So I was growing up in this segregated society even though I was backing Jimmy Reed when I was 14 at Lou Ann's in Dallas. We started our band when we were 12. It was a good band. Boz [Scaggs] was in it. We played fraternities all the time. It was 1956. I knew how to play and entertain people just from watching Les Paul and T-Bone Walker from the age of say 4 to 12.

AC: You were in Austin briefly in the mid-Sixties. What was it like?

SM: The University of Texas was the goofiest college I'd ever been to. I'd been to the University of Wisconsin for four years and the University of Copenhagen. I'd finished my run in Chicago and wanted to continue my education and because I was a resident of Texas I could go to the University of Texas very inexpensively. So I went down to Austin and enrolled in school, and then tried to enter the music department.

They let me take an advanced composition course; I was working on electronic music. I was listening to [German composer Karlheinz] Stockhausen and doing a lot of that. I was allowed to take an advanced composition course, but they wouldn't teach me how to read or write music. They said, "You can't enter music school."

So I hung around for three weeks. The music scene was good, but it was a little early. Just the brief time I was there I had some jams with some jazz guys. I can't really tell you who – maybe it was the 13th Floor Elevators [laughs].

I had come from Chicago where I had done the blues deal, so I knew what was happening. After spending about three weeks in school, I just woke up one morning and said, "Fuck this," sold all my books, put a bed in the back of my Volkswagen bus, drove to the highway, flipped a coin, and headed left – to the West Coast.

The Joker

SM: So I get out to the West Coast. The first night I'm there, it's the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Jefferson Airplane – at the Fillmore! It's 1966. And Paul, who I knew in Chicago, had [guitarist Michael] Bloomfield in the band. They're doing East-West and that sounds great.

But the Jefferson Airplane ... I go, "What the fuck is this?"

Same with the Grateful Dead: "What!? What's going on here?" It took me a long time to figure out, but I put my band together immediately and instantly became one of the staple bands at both the Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom, because I was a real musician. The Grateful Dead were high on acid, and were standing around for 25 minutes between songs and then doing a horrible version of "The Midnight Hour" or something that lasted 40 minutes.

It was crazy, but people loved it and it finally dawned on me that it was a social phenomenon, not a musical phenomenon, and these were guys who were folk musicians who went, "Hey, I want to be like the Beatles and grow my hair long. I'm gonna smoke pot, I'm gonna wear Beatle boots, I'm gonna get an electric guitar." They didn't know what kind of electric guitar to get or what kind of amps [laughs]. But they were very popular. They had the scene. I joined that scene and became a real working member of that community.

And it was a music community in San Francisco, as opposed to in L.A. or anywhere else. I mean bands actually got together and had community meetings. We played together, we worked together, we did free gigs in the park. We shared information. I remember after I did my contract with Capitol Records, I gave a copy of it to Quicksilver Messenger Service and said, "Here's what you need." There was a lot of that.

So, I drank the Kool-Aid, man. I believed in it. Then I spent the next seven years watching bands shoot by me. They had Bill Graham promoting 'em and I was just struggling. We put out Children of the Future, Sailor, Brave New World – five records in 18 months, I think. That's like 60 songs or something. We just kept working it. I would be playing the Grande Ballroom in Detroit, the Psychedelic Supermarket in Boston, and the Jefferson Airplane would be doing a Levi's commercial and making millions of dollars [laughs].

AC: When you wrote "The Joker," did you think, "I've got something here"?

SM: Nope. It was kinda funny, because The Joker was album number seven, the end of the line. And no one at Capitol Records had said, "Hey Steve, your contract's about to expire. We need to talk." They weren't even talking to me. I was doing 250 shows a year and they weren't spending a penny on me. They were making a lot of money off of me, because every time I put out a record they'd sell 200,000 or 300,000. They would make money, but they wouldn't spend any money on me, and I didn't have anybody representing me that they even knew or wanted to talk to.

The Joker, I made the album in 17 days and it was my last shot. I've told this story before: I was in my house in Marin County and I had ordered some wood. 8pm at night and this kid shows up with his truck and he's unloading wood. He's like, "Hey Mr. Miller, could you listen to my cassette? I'm a songwriter too." I said, "Yeah sure, kid," and I put on the cassette. "Jesus, this kid's music is better than mine," I thought. I'm sitting there pissed off at Capitol Records, and here's this kid, this really great writer, who's delivering a cord of wood to make a living.

So I kinda went, "Fuck this. I'm just gonna go down there and make the record." I cut the tracks in a couple days, then spent two weeks singing and overdubbing. Made the record, turned it into Capitol Records. They had a meeting and some kid said, "I, I think 'The Joker' should be the single." I said, "I don't even care about singles. I'm going to 60 cities in the next 90 days and all I want you clowns to do is get records in the record stores in those cities." That was it and I walked out.

Two or three weeks later, "The Joker" just went viral. We didn't have that term then, but that's what it did. It just went viral [eventually hitting No. 1]. Ninety days later when I got back to San Francisco at the end of the tour, I was driving to a theatre to play a gig – I think it was the Fox Theater in Oakland – and on the way over, "The Joker" was on four of the five radio stations. And I was pissed off it wasn't on the fifth station! It was played twice an hour, 24 hours a day, for a year on all AM radio.

So that song, hey, I wrote myself outta the ghetto, you know.

After that, when I started working on Fly Like an Eagle and Book of Dreams, I just ran into this mature area where I knew what I was doing. I cut all the tracks in 11 days with two other guys – a trio with Gary Mallaber and Lonnie Turner – then I took the tracks to my house where I had an 8-track tape recorder and a mixing console, and I overdubbed everything else myself over an 18-month period. Mixed 'em, turned 'em in, and I don't know, we sold about 14 million, 15 million, 16 million records over the next two and half, three years.

The Steve Miller Band plays the Skyline Theater on Tue., July 26. Big Head Todd & the Monsters open.