God Loves Ya When You Dance

Billy Joe Shaver's no wacko

By Doug Freeman, Fri., Aug. 17, 2012

Billy Joe Shaver isn't in the Country Music Hall of Fame.

A thick padlock hangs from the front door of the songwriter's modest house, tucked into a quiet neighborhood on the edge of Waco. In the driveway sits a white 1998 Dodge van with more than half a million miles on the odometer and a sticker slapped across the front bumper declaring, "If you don't love Jesus, go to HELL!"

The mailbox is emblazoned with an eagle amid streaks of red, white, and blue, though Shaver has his mail delivered to a post office box in nearby Hewitt.

"I get a lot of checks, written a lot of songs," he laughs in explanation of the padlock and PO Box.

Shaver, 73 on Aug. 16, hasn't just written lots of songs. He's penned some of the most indelible tunes in all of country music. His canon helped change the course of Nashville, most notably when Waylon Jennings cut his material on 1973's Honky Tonk Heroes, considered a foundational document of outlaw country.

"I came down here to get away from Nashville," offers Shaver. "I was getting into some heavy drugs and stuff, so I moved back down to Texas."

Clad in his hallmark jeans and blue denim shirt, Shaver ambles down his front hallway past a gallery of crosses and Native American dream catchers on the walls. In the tidy living room, only a photo of Shaver with his now-deceased dogs stands on the mantle. There are no family pictures. Those are clustered on the walls of his bedroom. Photos of his son Eddy, who died of a drug overdose in 2000, mix in with paintings of Jesus.

A wooden plank hangs above his bed, brandishing a phrase familiar from his performances: "God Loves Ya When You Dance."

"Waco's a polite bunch of people," surmises Shaver as he settles down at the kitchen table. "They don't bug you. Then again, you can't do hardly anything to get their attention unless it's something bad.

"Nobody noticed me until that shooting incident."

"That shooting incident" is the infamous 2007 shooting outside of Papa Joe's Texas Saloon in nearby Lorena – where Shaver shot Billy Bryant Coker in the face with a .22-caliber pistol. In the subsequent 2010 trial, the singer was acquitted of aggravated assault on grounds of self defense. Shaver offers his take on the events that night in his new single, "Wacko From Waco" (see sidebar).

"It's just a play song," says Shaver dismissively. "I hope it don't make a hit. God I'd hate to do that every night. I shouldn't be doing that. It's almost like bragging. I've been trying to wean off of it, but it's gotten popular."

Shaver's ambivalence toward the song encapsulates much of the songwriter's complex personality. He's a self-taught, hard-raised Texan with fierce bravado, but still often cast, even by himself, as the humble underdog. He's a fatalist to the past and forces beyond him, yet confident in his own capacity and in his deep faith in God.

"I'm just a really spiritual, kinda hardheaded religious guy," he ponders. "I'm constantly wondering if I'm doing the right thing. Every day and every second just about. And I realize now that people are listening to me, so now I'm very careful about what I write, because I don't want to hurt nobody. Actually, most of my songs, they were written trying to stay alive.

"The rest of them were written trying to get back in the house," he laughs.

Honky-Tonk Hero

Shaver's always been an outsider.

"I was not even born yet when my father first tried to kill me," he writes in the opening line to his 2005 autobiography, setting the stage for a life of tough endurance and close blessings.

Raised by his grandmother in Corsicana until she passed away, he was sent to Waco at age 12 to live with his mother and stepfather.

"I would run off though, because my stepfather and I didn't get along, and my mother didn't particularly like me either because I looked like my dad," recalls Shaver. "I'd go off sometimes and hitchhike all the way to Arizona or somewhere, just for the heck of it. I'd be gone for a week or two sometimes."

It's a personal history told throughout his songbook: "Georgia on a Fast Train," "Ain't No God in Mexico," "L.A. Turnaround," "Honky Tonk Heroes."

He joined the Navy at 16 and returned home to marry Brenda Tindell, whom he'd divorce and remarry twice. At 21, after a sawmill accident cost him two fingers on his right hand, he turned to what he felt was his true calling. Leaving Brenda and Eddy behind in Texas, Shaver planted himself in Nashville in 1966, securing a job as a songwriter for Bobby Bare's publishing company for $50 a week, and signing away the rights to some of his biggest hits in the process.

"It still puzzles me how people can be that goddamned cruel," bites Shaver. "They always believed that in Nashville, though – that a skinny dog would outrun a fat one, so they kept songwriters starved. It was pretty much slavery up there."

In Nashville, Shaver was rough-hewn and lacked business savvy, but his songs dealt in a hard-earned authenticity. Kris Kristofferson recognized Shaver's kindred talent, and recorded Shaver's "Good Christian Soldier" on his 1972 sophomore album, The Silver Tongued Devil and I.

Kristofferson also convinced Shaver to play the now famous Dripping Springs Reunion, forerunner to Willie Nelson's Fourth of July picnics. Backstage, Waylon Jennings heard the young songwriter and drunkenly promised to record an album of his songs. It took Shaver six months of harassing Jennings back in Nashville before he finally cornered the fellow Texan in a studio.

"I gave Waylon those songs, because I couldn't possibly deliver them like they were," notes Shaver. "They were too big for me. But Waylon had the experience and know-how. Now I can sing them, but then I couldn't. They were overpowering.

"I'd write 'em and think I was gonna die."

The success of Honky Tonk Heroes, with nine of its 10 songs penned by Shaver, signaled a new era in Nashville.

"It changed everything," laughs Shaver. "Chet Atkins had a fit because he knew. All those sequins and things kinda went out the door and we'd go in places with our blue jeans on. I caught all kinds of hell from old songwriters, claimed I hadn't paid my dues. I'd just say, 'Look [holding up his maimed right hand], where you have to pay your dues at anyway? Tennessee have a corner on that or something?'

"And I stepped on a lot of toes, rubbed people the wrong way," admits Shaver. "I was my own worst enemy. And like Townes [Van Zandt] and all these guys, we'd get messed up in a deal where they'd say these guys are unmanageable. So that hurt all of us. I guess I was kinda the ambassador of ill will there for a while, because I was causing trouble for everybody.

"I did a lot of it by just being me."

Live Forever

On a hot August night in 2001, Shaver stood onstage at Gruene Hall in New Braunfels. The heat surged densely under the stage lights with the crowd pulled in close, and he could feel the pressure building in his chest with every breath. The singer knew he was having a heart attack, but played on.

The band's guitarist, his son Eddy, 38, had died on New Year's Eve, and his wife and mother passed shortly before that. In April, Shaver had released The Earth Rolls On, a brutally powerful reckoning. It was his final album recorded with Eddy.

"I knew I was gonna die," sighs Shaver, the pain of the period still palpable in his voice. "I had decided, well, this is it. I just didn't have a lot to live for. I'd lost my wife and my son and mother – anybody that meant anything to me."

He performed over three hours that night at Gruene Hall, lingering later to sign autographs. Afterward, he spent the night at a motel in Pflugerville. Only the next morning did he check himself into a hospital in Waco. All but one of the arteries in his heart had blown out. A quadruple bypass saved Shaver's life, but it didn't ease the heartbreak over his son.

Shaver had pulled his son out of school when Eddy was around 12, taking him on the road with his hard-charging band, Slim Chance & the Can't Hardly Playboys.

"It was me, Freddy Fletcher, and Dave Pomeroy, and Eddy would play guitar," remembers Shaver. "They was a rough, ragged bunch, and when we started out, we couldn't play very good so we'd get drunk. We'd get drunk and puke on stage, and the people in the audience thought that was funny for some reason, so everywhere we went we'd do that. And then people got to where they'd come and they'd puke and it was the puking-est damn mess you'd ever seen.

"Eddy'd just blow through it. He'd say, 'You guys don't have any art.'"

As Shaver sobered up in the Eighties and was born again (see "The Christian Life," Aug. 14, 1998), Eddy's guitar pushed him in new directions. The duo recorded under the name Shaver through the Nineties, releasing four albums, including 1993's resurgent Tramp on Your Street and '98's haunting spiritual Victory.

In the early morning hours of December 31, 2000, Billy Joe received a call that Eddy had overdosed on heroin. That night, the band had been scheduled to play at Poodie's with Willie Nelson, but now Shaver stood in a hospital having just lost his son and getting few answers.

"Willie called down there and said, 'I got a band together and you're gonna play tonight,'" recounts Shaver. "'Gotta get back on the horse.' Willie had been through that. So I come down there to Poodie's, and Willie had a good band. I'd get up there every once in a while and do one, but he did most of it.

"It was hard – it was hard. But I did it and it helped."

Old Chunk of Coal

"There's something about writing in the middle of the morning, you get a littlelooser," proffers Shaver at his kitchen table.

He looks down and taps his hand against the wood.

"Eddy and me, we'd sit right here at this table, pretty sturdy little old table, and we'd call it Nights at the Round Table. We wrote some really tough songs here. We wrote 'Blood's Thicker Than Water,' and I mean, we'd have at each other. He was a great talent, great son, good guy, but he couldn't get away from drugs, them hard drugs. It was sad because he never got the credit he should have got."

Most of Shaver's work over the past decade has been an attempt to deal with Eddy's death, and reconcile the loss with his core faith. Freedom's Child (2002), Billy and the Kid (2004), and Everybody's Brother (2007) are all strafed with the still-daily struggle, yet bolstered by the cornerstone of Shaver's spirituality.

"Every day I wake up and I think about him," sighs Shaver. "But I don't think you're supposed to forget them. At my shows, a good percentage have lost loved ones in that same fashion. Usually they'll come back two or three times and pray with me. It's a good feeling, knowing you're helping somebody even though you didn't set out to help them. I just set out to help myself. I was just trying to write myself out of misery. I just did what I had to do to maintain."

That perseverance runs deep through Shaver's work. "Try and Try Again" has become a live staple, alongside the likes of "Old Chunk of Coal." Meanwhile, his other new song on Live at Billy Bob's Texas, "The Git Go," finds similar strength. While "Wacko From Waco" may get requests, "The Git Go" proves on par with Shaver's best material. Against its sharp, bluesy critique of war, greed, and politics, the seeming futility of struggling meets a sense of hope through dogged determination.

"I've had so many things happen to me that I can't be bitter, because I have to keep going," attests Shaver. "I've been near death so many times, it ain't no big deal. And I don't blame God for anything. You can't. You got the gift of life from God, and if you run into a pitfall or something, well, that's the breaks. You gotta get up and go on."

The Git Go

The first weekend in August, Billy Joe Shaver ascends the stairs to Antone's stage uneasily. He's recently had his knee replaced and surgery on his shoulder. Vertebrae are missing from his back, and a previously broken neck still bothers him.

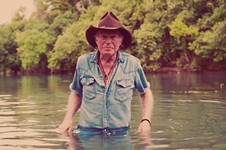

As he steps before the crowd, he lights up with a thick grin and doffs his cowboy hat to the cheers. A Billy Joe Shaver show is part sermon, part tall tales from the bar, as he weaves an arc of autobiography as introduction to his songs. He rips through his classics with fervor, shadowboxing against the beat of "Georgia on a Fast Train" and waltzing alone across the stage to "Honky Tonk Heroes."

At the heart of each show, the band turns its back to the crowd, Shaver hangs his hat from his respite guitar, and he beckons an a cappella "Star in My Heart." It's followed by the ever-poignant "Live Forever," with Shaver kneeling upon the stage through the closing chords.

"Love ya Eddy. Love ya folks," he calls heavenward.

And then as if to reaffirm his own message of perseverance, he launches back into the rowdy and raucous with "Thunderbird" and "Hottest Thing in Town." The crowd likewise breaks the stillness and erupts in a cathartic, joyous swing.

God loves ya when you dance.