Drums Across Texas

Battling bands, DIY caravans, and SWAC radicals converge on Nelson Field

By Kate X Messer, Fri., June 17, 2011

Close your eyes and you can hear it – the unmistakable din of a high school band room. That swell of horns and honking sax, the seesaw of ascending clarinets against descending flutes – none of it's changed. Note for note, the scene plays out generation upon generation.

A tall, good-looking man moves toward the center of the commotion, the din fading as it follows him, the clatter becoming murmurs cut only by the rustling of sheet music on metal stands.

"Shhhhhhh! Shhhhhh!"

Two girls slide into their seats just in time, woodwinds at the ready.

"Baritone bass clef? Baritone treble clef? Who else needs 'Most Girls'?"

Assistant coaches are earnest in their chop-chop, handing out the last bits of sheet music as players arrange their scores.

"Let's go!" barks the conductor as an oddly commanding electronic metronome begins ticking. A bleat of horns creates a wall of noise vaguely resembling the hit by Pink.

Director Ormide Armstrong wanders into the mass, focusing on different instrument sections take by take. The John H. Reagan High School band director is working this warm June evening on his other project, the Austin All-Star Band, composed of area band students and slated to perform at Saturday's Alvin Patterson Battle of the Bands & Drumline Competition, held annually around Juneteenth on their home turf at Nelson Field.

"Y'all, this is slow; we have to pick it up," he explains. "By tonight! The dancers are practicing to this song at its true tempo, and we are nowhere near close."

The group shifts gears. Sheet music for Rihanna's "What's My Name?" appears on the traditional black metal music stands. Three or four languid takes in, Armstrong, clearly frustrated, yet calm and focused, waves his arms to stop them.

"Listen!" he says to his back line of tubas, imitating them inhaling and spitting out air between notes, "You're dragging the beat!"

Meanwhile, the drum line has been outside honing its chops. During the next take, they drift into the packed, resonant room to join the rest. Like reunited battalions returning from the front line, this band of brothers and sisters is finally complete.

Brow furrowed, Armstrong beelines it back to his perch. The room is eerily silent. Front and center, he raises his arms. As if a choir of Berklee College of Music-graduate angels suddenly inhabited the kids' skins, notes begin to soar, percussion pummels, and the song's intended dynamics get good and tight. Stoking the momentum, Armstrong calls out.

"Turn around your stand! Turn around your stand!"

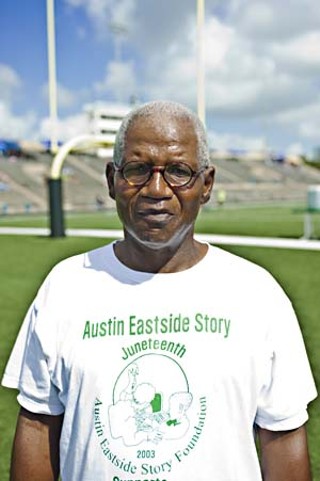

The group obliges, ready to tackle Rihanna sans sheet music. They chime in unison a martial chant ("Uhhhhhhhhhhh, A! T! X!"), then rip into a decidedly faster take. Onlooking parents exchange grins and glances, and heads begin to pop to the beat. An unassuming gentleman watches intently from the sidelines. Despite his calm facade, his stern and determined features belie an intensity of spirit. He could be any of the kids' grandfather, and with regard to this particular pending competition, he is – in spirit.

His name is Larry Jackson.

'Drumline'

Bands across Texas and around the region, from Louisiana to Georgia, come to compete in Austin's Alvin Patterson Battle of the Bands & Drumline Competition. Launched in 2004 to stimulate academic excellence, the Juneteenth celebration is named for L.C. Anderson High School's much beloved late educator and band director Alvin O. Patterson, who led his band to seven state trophies. Patterson attended the events named in his honor until his passing in June 2007.

"We found there were very few African-American children in band," says competition founder Larry Jackson. Out of Austin Independent School District's 84,000 students, only "54 African-Americans from 14 high schools were involved in band programs."

So he set out to change that. Jackson began the competition when he was executive director of the Austin Eastside Story Foundation. Currently, he heads up Austin's Joint Task Force on African-American Quality of Life for Education.

"Our ultimate goal is academic performance ... for well-rounded students," he explains. "There's a direct relationship between Reagan [High School] and Reagan's band and the fact that Reagan is not on [AISD's] closure list. Students here understand that if they are to participate in band and fine arts, they have to do well academically."

Schools and all-star bands are drawn to the battle of the bands because it spotlights the historically black college and university marching band tradition, a tradition that sizzles thanks to an ingredient most marching bands lack: soul. Historically black college and university traditions are carried by Southwestern Athletic Conference universities like Texas Southern, Grambling State and Southern universities in Louisiana, and Alcorn State and Jackson State universities in Mississippi. These programs have popularized "SWAC style," high-stepping that incorporates hip-hop, soul, funk, pop, R&B, and lots of strut, from knee-wagging stomps by the tenor drum section to the glinty swoosh of cymbals fluttering over the heads of the crash corps.

Not all schools find this style a valid form of study. SWAC style doesn't always fit in or place well at the University Interscholastic League, the inter-school organization formed at the University of Texas at Austin in 1909 to, according to its website, "provide leadership and guidance to public school debate and athletic teachers," as well as "educational extracurricular academic, athletic, and music contests." Here tradition rates high, and schools adopting the SWAC style have about as much a chance of placing at UIL as Kanye West does of getting booked at a George W. Bush Presidential Library Gala. Needless to say, SWAC is popular with youth.

"This style of music is a crowd-pleaser," says Jackson. "Especially to young people. At the Cotton Bowl, they would have 80,000 people show up for the Grambling-Prairie View game, and 60,000 of them showed up for the band."

While the subtext implies a breakdown around racial lines, colors and cultures blur.

"What started out being geared for African-Americans," says Jackson, "turned out to be something Hispanics are taking advantage of, and I for one am happy for all of that.

"I saw the movie Drumline when it came out and said to myself, 'That's what we need here,' because it attracts kids from all racial [backgrounds]. Plus, even narrow-minded groups can't be opposed to children having fun."

Jackson, whose history underlies a radical heritage, finds that SWAC-style empowerment runs right up his alley.

"In school, I played the trombone," he recalls. "I, like most African-American males, however, was geared toward sports. So I put my trombone down, and I did sports. I ended up putting all that down to become a social activist."

Street Team Radical

Born in 1947, Larry Jackson came out of the Bryan-College Station metroplex, a native of Hearne. His father was Navy, stationed on the West Coast, so Jackson was sent to live with an aunt in California.

"[It was] the first time I went to an integrated school, La Cienega Elementary in Los Angeles," recalls Jackson. "I learned things I was not accustomed to, being from the South, like [when addressing teachers with], 'Yes ma'am,' and 'No ma'am.' They instructed me that it was 'yes' and 'no,' with no 'ma'am' to it. They felt my saying 'ma'am' was acquiescing to slavery.

"I was introduced to all kinds of things, like the L.A. symphony and swimming pools ...."

Integrated swimming pools.

"Where I was from, we had no pool. There was a pool, but it was for whites only."

According to Jackson, he wrote a letter to President Kennedy asking for a pool for Hearne.

"In the process, I received an invitation to Rice University in Houston, where President Kennedy was going to be. After they found out I was a teenager and not an adult, they contacted Texas A&M, which ended up contacting the city of Hearne. We got our first swimming pool."

Douglas Staten, a contemporary of Jackson's in Hearne, has stayed in touch.

"Mr. Jackson, at that particular time," giggles the onetime school board president at Hearne ISD, "I would characterize him as a little radical.

"Larry's not one that goes around tooting his horn," Staten continues. "He prefers to do things below the radar. He's an idea man and surrounds himself with individuals who can put those ideas in place."

Later, Jackson went to live with another aunt in Houston, where he attended Kashmere High School, famous for its award-winning jazz band throughout the 1970s, as documented in Mark Landsman's film Thunder Soul (see "Kismet in Kashmere," Screens, March 12, 2010). Jackson's tenure there predated the Kashmere Stage Band era, but the coincidence resonates. During this time, Jackson began connecting with state and national civil rights activists, meeting future Rep. Barbara Jordan at Texas Southern University.

"I stayed up the street off Lyons Avenue [in Houston], where she stayed," he recalls. "I had a speech impediment. She always told me to work on breathing to improve my speech. To choose my words. She said that people would always interpret a speech impediment as a mental impediment. I always remember that."

Jordan was but one legend of civil rights significance whose path Jackson would cross.

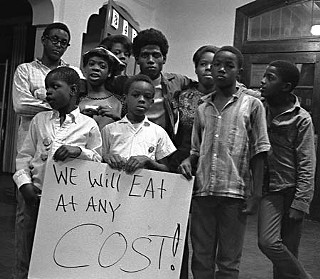

Jackson became part of what nowadays might be called the street team for Stokely Carmichael and H. Rap Brown who, before their international notoriety as members of the Black Panthers, appeared at the University of Texas as part of an anti-war speaking engagement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the youth group affiliated with Martin Luther King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Soon thereafter, the burgeoning radical was drafted for military service, after which he enrolled at UT with some well-placed influence from then-UT Dean John Silber, now president emeritus at Boston University and previous Massachusetts gubernatorial candidate. Silber's office sent the following statement:

"Larry Jackson entered the University of Texas full of energy and personality. His early initiatives sometimes answered to particular social needs but were contrary to [UT] policies. In time, he developed projects that could be supported by the University and greatly increased his influence. He was clearly a leader with intelligence, ideas, and a great deal of charisma. I'm pleased but not surprised to learn he continues to work with African-American youth."

"Out of that," Jackson points out, "I started Child Inc., which here is the Head Start free-and-reduced-lunch program in AISD."

Working with or on the political campaigns of Austin progressives Gonzalo Barrientos, Wilhelmina Delco, Gus Garcia, Lloyd Doggett, and Richard Moya came next. And drum lines?

"Music is a means to reach people," says Jackson, still talking progressive politics. "Now there's all kinds of music, all styles, but music is where young people have a united ear."

Pacific Ocean Boulevard

A teen gnaws on a lollipop and slings her arm across her friend's shoulder. Their booties bump to imaginary beats – imaginary because it's smooth jazz oozing out of the PA. That's how the band director likes it, and it's his fundraiser.

"This is our last car wash," he laughs. "A lot of the kids graduated yesterday and some today, so they're just kind of dragging tail."

Cymbal-slinger LaTonya Watson isn't one of the tail-draggers. Her incandescent grin outshines the Texas glare. Today's car wash raises funds for another of Larry Jackson's ideas: the Southwest Bound Marching Band Caravan University and College Tour, which takes the Austin All-Stars, Houston All-Stars, and Johnson School of Performing Arts from Killeen/Fort Hood on a weeklong tour of colleges and sites along the route between Texas and the West Coast. Watson's loyalty to Jackson, Armstrong, Reagan High, and the Austin All-Star group is clear. She's not going on tour since she graduated last night and is preparing for her freshman year at Texas State, but here she is on Saturday morning scrubbing cars alongside the dozen or so bandmates resisting the temptation to snap towels and spray one another with hoses.

"Mr. Jackson is so inspirational, what he does for us kids," she gushes.

This unprecedented SWAC-style high school band tour will take a caravan of buses packed with teenagers and chaperones across Texas to Balmorhea State Park; UT-El Paso; New Mexico State in Las Cruces, N.M.; and Arizona State in Phoenix; to Los Angeles and Palo Alto, Calif., to tour UCLA, USC, Cal State, and Stanford; to Las Vegas for a visit to the University of Nevada at Las Vegas and a performance at Circus Circus; and with additional performance stops at the Grand Canyon, the Hoover Dam, Venice Beach, and possibly the Facebook headquarters. Former Motown marketing Vice President Jonathan Clark, a Cal State and USC alum collaborating with Jackson, is using his connections to get the kids on a shared bill at Blair High School in Pasadena, Calif., with R&B/jazz artist Lalah Hathaway as well as booking a tour of Stevie Wonder's radio station, KJLH.

"We want to leave an indelible impression on these kids," says Clark, "not just for the academic experiences, but to let them see the sun set over the Pacific Ocean."

Armstrong notes that due to the group's SWAC connection, the kids are "always looking at the SWAC schools, but it's good for them to see that there's more out there. There are more educational opportunities out there if you look for them. It's going to open the kids' eyes to different college opportunities."

"My whole purpose has been to bring about change in the community," insists Jackson, whose radical path of sticking it to "the man" has lead him to the cultural progressiveness of this current endeavor. "My whole goal is to do these things with no public funding. For instance, the Battle of the Bands has no budget."

One nerve center of band mothers is all abuzz behind the Reagan High band room. As the band runs through its paces, details of the coming tour are falling into place. Michelle Dean, whose son, Austin High School student Jacob Ruegg, is touring with the All-Stars, is hard at work. She and four other mothers are sorting medical releases and tour waivers and working out the dollar details. Between parents and other connections in AISD, the hustle is on to secure cheap or free lodging, mostly on school campuses, as well as food – their lunch cards work nationally at any public school cafeteria. The car wash is an opportunity for the kids to take care of their share. Local bus company Star Shuttle has negotiated a reasonable rate per rider. Jackson's dream of keeping the tour at a zero-fundraising budget may just come true after all.

"He's always had big visions," Armstrong says of Jackson and his dedication to the kids and the opportunities he's created for them. "He's just been a blessing to me, to Reagan High School, and to the band program. It's a testament to his character, to never give up on us when everyone else did."

Working at the Car Wash

Two cars line up as the kids begin to clean.

"You heard what I said," Armstrong insists. "I don't want to see you just standing around. These people are giving you money so you can go on this trip."

His job today is herding cats. Wet, sluggish cats.

Meticulously scrubbing the grill of the first car, one older gentleman has his head down, set to the task at hand. So intent, so quiet, so eyes-on-the-prize, Larry Jackson hardly notices that our interview is about to begin.

The eighth annual Alvin Patterson Battle of the Bands & Drumline takes place Saturday, June 18, 6pm at Nelson Field, 7200 Berkman, just east of Reagan High School. Tickets are $15 at the gate and $10 advance purchase from Mitchie's Gallery, 7801 N. Lamar #148, Bldg. B, 323-6901, www.mitchie.com.