The Miller's Tale

Ernie Mae Miller still takes requests

By Margaret Moser, Fri., July 6, 2007

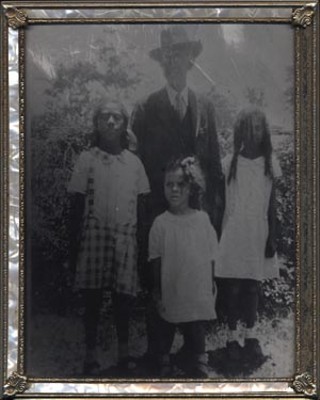

Ernie Mae Miller holds in one small hand a framed photograph from the Forties. It's a band photo of the Prairie View Co-eds, the black, all-girl swing band from Texas that toured nationally during World War II. Miller's index finger rests on a pretty girl with a Texas-sized pompadour holding a baritone sax.

"That's me in the Co-eds. We played USOs, Army bases, New York City, and the Apollo Theater. There were 16 of us playing that night at the Apollo." Her misty voice is soft as remembrance, and she tilts her head as she looks at the other girls. "Some of them are dead now."

Miller sets the photo back on the glossy top of her baby grand piano, then settles with a sigh of arthritic stiffness in to a cushy print sofa. Two stacks of press clippings from seven decades of performing music sit before her, ones she ritualistically brings out for visitors and reporters. Dressed in a flowing print blouse with terra-cotta slacks, her shot-silver hair in arranged waves around her round, ageless face, Miller looks at the yellowed newspaper and out-of-print local and state magazines.

"If anybody is writing a history of Austin, I got stuff they can use," she offers, lifting her head and gazing over her glasses to the array of family photos lining the fireplace.

Ernie Mae Crafton Miller, 80, was born in 1927 to Otto and Lizzie Anderson Crafton and raised in Austin. A debutante in the Eastside's social organization the Cosmopolite Club, Miller was sponsored by an illustrious family that made its name in education, government, and Lone Star real estate.

After touring with the Prairie View Co-eds, she settled in the state capital and over the decades crossed racial boundaries playing piano for Austin's best-known restaurants and hotels. Among Austin's legendary pianists such as Robert Shaw, Erbie Bowser, and Roosevelt "Grey Ghost" Williams, Ernie Mae Miller takes her place with everlasting honors.

Eyewitness to the Past

"My great-grandfather's name was Willis. That was in Tennessee, in slavery times. When my grandfather was born in 1853, he had to take the slave owner's name, Anderson. They didn't use Willis again. He had two brothers, and they all used Anderson. They're buried here in Oakwood Cemetery."

The words resound without rancor from Ernie Mae Miller. Slavery times. Slave owner. To hear Miller talk is to hear a sometimes bone-chilling oral history. She's eyewitness to eight decades of changes in Austin's black population.

"My grandfather L.C. Anderson finished Fisk University, way back in Nashville, Tennessee. He became president of Prairie View before he started with high schools. He taught school, at the first old high school here [for blacks], behind Ebenezer [Baptist] church," she gestures, waving a hand familiarly.

"It was just a little shotgun house over there by 11th Street and San Marcos. They called it Robertson Hill then. They built a two-story school on Olive Street that was the first large high school. It was named for my uncle Ernest – that's who I'm named for – and my grandfather was principal there and then at the new high school on Pennsylvania Avenue. That one was named for L.C. in 1938. The Robertson Hill school burned, but it had been made an elementary school by then. That's where I went to school. It's not there now; a park is there."

Miller speaks as if she still lived in her grandfather's house at Navasota near 12th instead of the comfortable suburban two-story in far East Austin with one of her six sons. She speaks of those sons with motherly affection and notes 14 grandchildren and step-grandchildren between them but still confesses wistfully "not a girl there. I really did want a girl," before continuing her tale.

"I can see why the school burned. I remember it had old potbelly stoves. The janitors would come fill them with coal, and they would get red-hot. It got so hot in there! But then they built an Anderson high school out on Hargrave, then the new one on Mesa Drive."

The story of the Anderson brothers is even more integral than Miller elaborates. Both studied to be Methodist ministers, and L.C. taught alongside Booker T. Washington in Tuskegee, Ala., before joining Ernest, better known as "E.H.," in Texas. The two young men were among the original eight blacks to enroll at the newly opened, state-supported Prairie View Normal Institute in 1876, only 11 years after the abolishment of slavery in Texas. Prairie View's purpose was "to establish an agricultural and mechanical college of Texas for the benefit of colored youth."

Prairie View became Prairie View State College and later Prairie View A&M University, where both Andersons served as president. It was only fitting that Ernest Mae Crafton – indeed named for her maverick uncle – also attend college there.

Winding the Victrola

"My grandmother had an old windup Victrola. I was a little bitty ol' girl, and I'd stand up on the stool, and she'd let me play her records. I'd play 'Blue Skies' and 'Melancholy Baby' and fall asleep listening to them. I loved to wind that Victrola and play those old 78 records.

"I learned a lot of songs from that, popular during my time. I still play them, 'Tea for Two,' but I jazz it up to make it sound a little modern. I always liked Gershwin songs, too, 'Rhapsody in Blue' and 'Summertime.'"

Some of Miller's musical inspiration came from the venues of the day, places like 11th Street's Cotton Club, which booked some of the biggest names of the day, including the Duke Ellington and Count Basie orchestras. Next door was the Paradise Inn and its forbidden jukebox luring Miller and her friends.

"I used to go to the Baptist young people's group, Sunday evenings, at Ebenezer. One night we went out the back door and down to the Paradise. My mama heard about that. She came with a switch and switched me all the way home."

The switch didn't dissuade Miller's love of music. During her school years, she learned to play baritone sax and piano. Sax was the instrument she played in the band at L.C. Anderson High School, under the direction of B.L. Joyce. Joyce taught several generations of Austin's black musicians because there was only one black high school. Joyce's long string of bands won their share of awards over the years until his retirement.

Primed by her years performing under Joyce, Miller entered college after graduating high school in 1944. At Prairie View State College, she joined the Prairie View State College Co-eds.

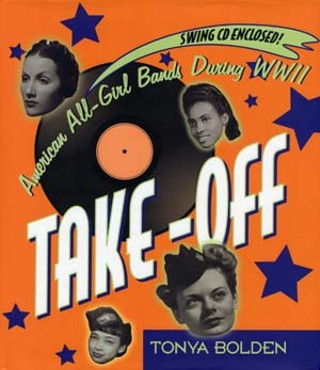

Photo from ‘Take-Off: American All-Girl Bands During WWII’

"There were four or five different girl bands at this time: the Sweethearts of Rhythm, the Darlings of Rhythm, us ...."

Miller rises from the couch and moves toward the bookshelf, pointing to Tonya Bolden's Take-Off: American All-Girl Bands During WWII and Sherrie Tucker's Swing Shift: "All-Girl" Bands of the 1940s.

"There are books about those bands. This one has a CD, but we're not on it. I don't think the Co-eds made any recordings."

At the piano, Miller looks at the framed photos of her standing backstage at the Apollo, with the Co-eds, wearing her white deb gown and a silver sash. "I had enough hair so that I didn't have to use a bun," she chuckles.

"I didn't finish college. I got to be a junior, and when I was offered this band in New York, I went. I met a guy and married him in St. Louis, but it didn't last."

Motherhood and a failed first marriage gave Miller the desire to return home. She moved back to Austin in the late Forties, staying with her mother while she finished college at Huston-Tillotson. There she met her second husband.

"We lived by 12th and Navasota near the Dukes' – you know [Rep.] Dawnna Dukes? They lived on Waller, right behind us. Dawnna's mother said, 'I got a fellow I'd like for you to meet.' She had a dinner at her house and invited a boy who was on furlough.

This marriage did last, producing five more sons for the couple.

"It's Hammitt, like dammit," jokes Miller about her late husband, who died in 1977.

Hammitt Miller worked at the post office as a mail handler, but with six boys and finances stretched thin, Ernie Mae decided to return to work as a musician but switched to piano because Hammitt "didn't care for me touring with men." Thus she began her career as a piano soloist. Her first major gig was playing Dinty Moore's restaurant.

"Dinty Moore's was across from the old, old post office on West Sixth," she recalls. "It was a straight hall, and the grand piano was at the back. One night, a rat came around, sat on top of the piano, and crossed his legs, looking ever so charming with the music! I couldn't jump up because I didn't want people to know a rat was there. He finally just walked off.

"After that, I played the Driskill on the Sixth Street side. They had a bar. It was different then, but that's where I played. My mother was Downtown one day, and she went in there. She told a man, 'Don't you have a piano player? My daughter plays piano.' They called me, and I stayed there a long time.

"Somehow the Lord took care of me."

You Shocked My Modesty!

Miller's best-known gig began in 1951 at the New Orleans club on Red River, then the western edge of the 11th Street entertainment district on the Eastside.

The New Orleans club was one of the most famous venues of the day in Austin, catering to a middle-aged, white clientele with a taste for Dixieland jazz. In the early Sixties, the 13th Floor Elevators would play to large crowds there.

For her part, in the beginning, Miller kept more traditional audiences happy in the downstairs' Creole Room, decorated to suggest the French Quarter, with bistro chairs, tables, and familiar New Orleans scenes painted on the walls.

"Downstairs was the lobby. They didn't dance downstairs, but there was dancing upstairs. Upstairs was a garden where they had bands, lots of greenery. [Later], the hippies used to come see me. One time it poured rain, lightning and everything. My new red suede shoes were ruined going across the floor! It flooded that time, but I got home safe.

"During the winter they'd put coal in old washtubs. The Fire Department made 'em take it out because it was dangerous. The Creole Room was well-insulated, though. You got all your drinks at the bar downstairs."

Piano playing wasn't her only talent. Miller's sweet honey voice suited the music she played, prompting comparisons to jazz greats of the day like Billie Holiday. She recorded a live album, At the New Orleans, in the early Sixties, a sampler of her most popular songs such as "My Man," "When the Saints Go Marchin' In," and "Blowin' in the Wind." The latter song was hardly typical of Sixties cocktail music, but it remains indicative of Miller's appreciation for musical variety and social conscience.

At the New Orleans posits Miller as the leading black female performer in Austin during the Sixties. The song selection also includes the Rodgers & Hart song, "Little Girl Blue." Is it a coincidence that Janis Joplin also recorded "Little Girl Blue" on her 1969 album, I Got Dem Ol' Kozmic Blues Again Mama!? Probably, because it was a popular tune of the day, though Miller was at her career height when Joplin lived in Austin and was keen to experience anything resemblingthe blues.

During her years at the New Orleans Club, Miller accrued the bulk of her notices and press. UT's The Ranger, The Dallas Morning News, Austin Homes & Gardens, and all the local papers raved about her. "The Pied Piper of the keys" she was dubbed in a column blurb. "A little blues and a little bawdy," yet another story on Miller began. That phrase set her storytelling.

"One night, I was playing 'The Ice Man,' which is, a little 'off.' You know, 'How about a little piece today?' A lady was there – I won't name her name – and she said, 'You have shocked my modesty! I'll never come here again!'

"Nat Henderson from the Statesman was there. 'Aw, shut up!' he said as she went out the door. 'You know you slept with the president last night!'

"Everybody fell out of their chairs laughing."

The lilt in Miller's voice is irresistible, and the smile on her face says that she knows more to this story than she lets on.

"I didn't play just that music. I played all the songs that were popular. Most of the old songs I just knew: 'Sweet Georgia Brown,' 'St. James Infirmary,' 'Blue Skirt Waltz.' After the games I'd play 'The Eyes of Texas,' and people would stand up."

"Austin's been very good to me. I'd get out of one job and into another."

Encore

In the 40 years since her New Orleans club gig ended, Ernie Mae Miller has continued to play, usually for money, but just as often to please herself. And oh yes, lots of residencies and shows at vintage restaurants and clubs such as the Flamingo Lounge, Jade Room, Jester's Club, Longhorn Bar and Grill, Steak Island, the Cedars, and Commodore Perry Hotel in those long-gone days.

"I played the Commodore Perry Deck Club. The building is still there, but it used to be a hotel with a swimming pool in the floor. One night a waiter came in drunk. Someone had ordered a lot of steaks, and he had his tray full of them. He walked into the pool thinking it was the glass dance floor."

The memory tickles her to no end, and her gentle laughter fills the cozy room. And just what does Ernie Mae Miller do with her days? She spends much of her time at home, where a small rehearsal space in back of her house is her refuge. It's outfitted and decorated like an apartment. That's where her little grand piano sits – another piano is inside her house – and "every day I'm on that piano."

Miller lives on her Social Security and stays busy "keeping house, playing special jobs," and performing at the occasional honor for politicos, at Austin's social gatherings, and private parties for local luminaries. She contributed a track to 1997's I'll Be Home for Kwanzaa, recorded live at Top of the Mark with Martin Banks, T.D. Bell, Pam Hart, and others. That At the New Orleans vinyl, by the way, goes for upward of $50 on eBay.

Ernie Mae Miller recently has done what every respectable musician does: She's gotten herself a regular gig. ![]()

Ernie Mae Miller plays the Radisson Hotel's TGIF Red, Hot & Blues Brunch, every Sunday, 11am-2pm, through August.