If You're a Viper

A slightly dazed but hopefully not confused, totally subjective, and woefully incomplete overview of marijuana and music

By Margaret Moser, Fri., May 25, 2007

Photo courtesy of Shawn Sahm

"Dreamt about a reefer 5 foot long.

Mighty Mezz but not too strong.

You'll be high, but not for long

If you're a viper."

Who wrote the first song about smoking pot?

It's been lost to history, but here's a political side note to the 4:20 generation: During the Mexican Revolution of 1910, thousands of native Mexicans moved north across the Rio Grande, many settling around San Antonio. With them came a curious song called "La Cucaracha," known perhaps apocryphally as Pancho Villa's theme song.

"La Cucaracha" crackled with life, a swaying Spanish-tune-turned-Mexican corrido quickly picked up by jazz bands and danced into popular music. No song better evoked the languorous image of life south of the border in vintage films, newsreels, and radio programs of the day. Few people realized the lyrics bespoke a cockroach's yearning to stay high.

"La cucaracha ya no puede caminar ... por que no tiene marihuana por fumar," basically translates as, "The cockroach can no longer walk because he doesn't have any marijuana to smoke."

There you have it. Hidden in the foreign words of a hit song, pot smoking permeated popular American culture. Kinda makes you wonder if, after the bloodshed ceased at the Alamo, a victory bowl was passed around.

Viper Blues

Think Louis Armstrong burned a fatty when he played Austin's Driskill Hotel in 1931? Round his native Storyville, on Basin Street in New Orleans, marijuana had long been celebrated in music, reflecting the ancient neighborhood's Jazz Age lifestyle and red-light back streets. "Muggles" was his musical interpretation of a joint smoked in 1928, and "La Cucaracha" nested in his repertoire. He'd already been rousted for pot at least twice and spent a few days in the pokey.

Frankie "Half-Pint" Jaxon wins the prize for the oldest authenticated American song about marijuana, 1927's "Willie the Weeper." He and numerous other jazzmen and women celebrated smoke in songs of the era such as Cab Calloway's "Reefer Man," Fats Waller's "A Viper's Drag," Milton "Mezz" Mezzrow's "Sendin' the Vipers," Bessie Smith's "Gimme a Reefer," and Stuff Smith & the Onyx Club Boys' "You're a Viper."

"Vipers" are what the marijuana enthusiasts of the Twenties called themselves, and they wrote their anthems en masse: "Here Comes the Man With the Jive," "Viper Blues," "Jack, I'm Mellow," "Sweet Marijuana Brown," "Viper Mad," "Tea Party," "The G Man Got the T Man," "The Stuff Is Here (and It's Mellow)," "All the Jive Is Gone."

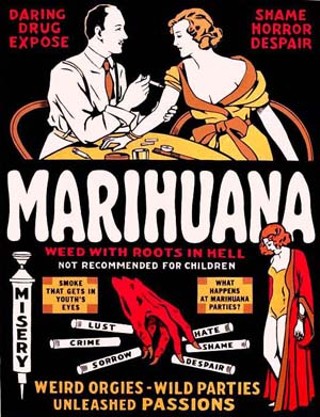

This exuberant musical activity was in harsh contrast to the official depiction of marijuana by the government, which had taken a dim view of Mexican immigrants. As various anti-hemp interests such as the cotton and petrochemical industries grew influential and anti-marijuana crusaders like Harry J. Anslinger gained authority, the stereotype of lily-white American teens being perverted by hopped-up, hot-blooded Mexicans was more than a mythical smokescreen. It was fantastic fodder for the Hearst press. A document on the history of the San Antonio Police Department 1910-1920 from the city's official Web site is revealing:

"Newspaper clippings from this decade begin to note problems with narcotics in San Antonio, including opium and marijuana. An article of 1913 pointed out that marijuana was grown, cured, and smoked in SA, and the town forms the distribution point for the southern territory."

The end of Prohibition brought the Depression. The Depression brought with it a renewed campaign on the part of the United States government against marijuana. As commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, Harry J. Anslinger declared "reefer makes darkies think they're as good as white men." Once again the suppression of marijuana was a racially motivated political tool. Not only were Mexicans going to lure your little darlings into their dens of iniquity, blacks would provide the soundtrack.

Anslinger's appointment as commissioner of the FBN in 1930 sealed his anti-pot mission. Pharmacies stocked marijuana up until 1937, when Congress passed the Marihuana Tax Act. The name of the bill was deliberately misleading as the intent was to ban marijuana – which literally grew wild around the country – production outright.

What a contrast to the country's founding fathers, who'd opened the Colonies' doors to hemp in the 1600s! The Virginia Assembly of 1619 required all farmers to grow hemp. Its strong fibers were commonly used to make clothing and sails, and it was considered legal tender in three states. That respectable history vanished almost overnight with the appearance of anti-marijuana films, most notably the church-bankrolled Tell Your Children, better known as Reefer Madness (1936).

A scare campaign like that might have worked a few decades before, but the era of mass communication was upon America. News and information, once disseminated only by newspapers or posted handbills, blared from the radio for all to hear. Even silent films evolved into talkies, and the filmgoing audiences ate up newsreels as fast as feature films.

Although the portrayal of marijuana as demon weed was fed to teens, the campaign had the opposite effect. Coming from the wild days of Prohibition into the Depression offered few alternatives for youthful pleasures. Their limited world was enhanced by the suggestion of something wilder happening out there.

"The reefer man is here!" sang out Cab Calloway.

Dope and Delinquency

"Ever hear of Smokey Wood & the Woodchips?"

Ray Benson is on the phone, calling from the Playboy Mansion out in California, where his band Asleep at the Wheel is about to perform for the Marijuana Policy Project, a campaign to legalize medical marijuana.

"Smokey was an obscure Western swing artist from Oklahoma who worked mostly around Houston and Dallas," says Benson. "Nora Guthrie sent me some writing Woody did when he was sick, and one line in a poem about Smokey went, 'I taught Smokey how to drink, and he taught me how to smoke stick.' That was him. He was known as a pot-smoking, whiskey-drinking, womanizing, fun-loving Western swing guy."

Maybe Smokey was a little too fond of weed. The Arkansas-born Wood moved to Oklahoma as a child, but his musical career centered so much in Texas that he was known as "the Houston Hipster." Wood played in a series of bands near the end of the Thirties – notably the Modern Mountaineers with fellow pothead and ace fiddler J.R. Chatwell – and his love of smoking dope was notorious, as he would spend his days high and even light up onstage. His appetite for pot was such that he carried not just bags but pounds of it around.

Wood worked part time in a Houston gas station, where the job consisted of filling tanks, wiping windshields, and selling pot in quantity. He continued performing, but he and Chatwell were booted out of a Bob Wills side project for living the nightlife instead of playing it. Wood played and recorded sporadically through the end of his life, but it was an itinerant one. He moved around a lot, played the carnival circuit, ran a flea market, and mostly raised fighting cocks and grew marijuana until his death in 1975.

J.R. Chatwell was also known to be a good-time kinda guy.

"Chatwell was a great fiddler," Benson recounts. "A mentor of Doug [Sahm], he was smoking pot in the Twenties. He played with Cliff Bruner's band the Texas Wanderers with Moon Mullican on piano, with Adolph Hofner & the Pearl Wranglers, with legendary bands. He even played with Doug in the Seventies. If you rolled a joint with a seed in it, and it popped while smoking, J.R. would yell at you. He was the granddaddy."

A 6-foot-6-inch Texan named Link Davis made quite the impression in the Fifties on a young fiddler named Johnny Gimble. Ray Benson recalls asking Gimble about Davis.

"Johnny said, 'Oh yeah, I played with him down in Houston in the early Fifties. Link was a hepcat!' Now, hepcats were guys who wore zoot suits and were into black culture and jazz and stuff, Gimble said. 'Link Sr. would get onstage and smoke a pipe with pot and tobacco mixed in it!'"

Now that drugstores were rid of the tincture of cannabis for medicinal use and the Marihuana Tax Act was in place, high-profile musicians were often targeted for busts. "Dope and Delinquency," shrieked headlines when jazz drummer Gene Krupa got popped in 1943. Anita O'Day was his singer at the time and not involved in that bust, but four years later, she and her husband were arrested for possession, for which she did jail time. She was busted again for pot in 1952 before falling into heroin addiction.

If Armstrong, Calloway, and Krupa whetted the public appetite for pot, scores of musicians followed. Duke Ellington, Bing Crosby, Billie Holiday, Count Basie, Jimmy Dorsey, and Dizzy Gillespie were among the thousands toking and smoking as a way of life.

"Are you hep to the jive?" was code for "are you cool, man?" For those who didn't know the slango, Cab Calloway wrote his Hepsters Dictionary, a guide to the genre's double-talk, in 1938, as did a Texas piano-playing radio personality named Lavada Durst. Better known as Dr. Hepcat, Durst started on radio in the Thirties, the first black disc jockey in Texas. He later ruled the airwaves in Austin on KVET, though his book, The Jives of Dr. Hepcat, wasn't published until 1953.

Marijuana was making its mark in American culture in other ways. Artists and film people got onto it nearly as fast as musicians. The Fleischer brothers made three stylish cartoons in the Thirties featuring Cab Calloway songs, and one was the druggy "Minnie the Moocher." In 1943, Warner released the unfairly censored "Coal Black and de Sebben Dwarfs," whose hot jazz matches a gorgeous cartoon to which racial interpretations have been attached. "The Hep Cat" was also a popular Warner Bros. cartoon of the day, and in 1946's "Rodeo Romeo," Popeye saved the day by ingesting "loco weed" when no spinach could be found.

A photo of actor Robert Mitchum at the police station, busted in 1948 while lighting up with a Hollywood confection named Lila Leeds, says it all. Mitchum, who later had a hit song about bootlegging called "The Ballad of Thunder Road," is typically sleepy-eyed but looking unapologetic, rebellious, and maybe a little amused. When asked about his subsequent jail time, he cracked, "It's just like Palm Springs without the riffraff."

Smoke Gets in Your Eyes

The Fifties was an unprecedented era for youth films with the emergence of the juvenile delinquent. Exploitation films like 1955's One-Way Ticket to Hell (aka Teenage Devil Dolls)

and serious cinema like Blackboard Jungle had one basic message: Your children will listen to rock & roll, smoke pot, and go to hell in a handbasket.

The bond between marijuana and music remained the domain of outsiders, the hip, experimental, underground descendants of the vipers and hepcats called beats or beatniks, who were like smart hippies with short, cleaner hair and better taste in music. The image of the goateed hipster with a beret and Buddy Holly glasses often found its way into Playboy and New Yorker cartoons.

At the end of the Fifties, that image was beamed by cathode ray into American households as the character of Maynard G. Krebs on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. Bob Denver played Krebs, though he's much better known as Gilligan from Gilligan's Island. Krebs was a lovable, bumbling, unwashed beatnik, which was contrary to their philosophical jazz-loving, bongo-playing, pot-smoking media stereotype.

Other beatnik stereotypes were perpetuated through cult films such as 1958's The Cool and the Crazy and 1959's The Beat Generation but were firmly planted in the public's consciousness in a more benign way: television. When the popularity of television exploded, stations started scrambling for filler, often using old movies. It was the cornucopia of cartoons spoon-fed to the early TV generation that gave many viewers their first taste of hip jazz culture.

These cartoons were never intended to be shown repeatedly, nor were they meant for television audiences. Their dialogue was witty, and cultural references could be wickedly obscure, literarily based, or both. They were associated with film studios, and particularly Warner Bros. cartoons lampooned the studio's films and stars and crackled with dynamic soundtracks. It's the cartoon depictions of jazz and swing bands that resonate. Forget the racist aspect, the exaggerated facial features. The culture being portrayed was the marijuana culture, and it wouldn't find a strong identification with American blacks again until the 1990s.

In 1937's Harman-Ising short "Swing Wedding," a trumpet mouthpiece morphs into a syringe though which Fats Waller, Bessie Smith, and Bill "Bojangles" Robinson are beautifully cartooned, as is the more caricatured "Voodoo in Harlem," a Walter Lantz production. Then there's a bizarre Mighty Mouse episode in 1944, "Eliza on Ice." Long censored cartoons like these as well as racially charged World War II toons were easily found as Saturday morning fare for the Mickey Mouse Club generation ready to lift marijuana from the gutter to the curb.

Is it any wonder they were ready for the Sixties?

One Toke Over the Line

Forget the rumor that "Puff the Magic Dragon" is about pot smoking. It's not, says co-author Peter Yarrow. This is plausible because if his intent really was to hide drug references in an otherwise bittersweet folk ditty about childhood's end, he could have done much better. This nondebate is symptomatic of how marijuana was debunked in the Sixties only to become even more mythologized.

Is it really possible, as claimed, that John Lennon's flip remark about the band being "more popular than Jesus" led to close scrutiny of them and a series of busts in 1967? If Dylan hadn't gotten the Fab Four to puff the stuff, would there have been a Sgt. Pepper or Rubber Soul?

Once again, youth-exploitation films like Riot on Sunset Strip and Maryjane led the way, but this time TV followed like a doddering grandparent, nattering and shaking its finger via Dragnet. Jack Webb directed and starred in the show from 1967 through 1970. Its grossly caricatured cast once again titillated the youth of America with hysterical depictions of groovy crash pads, hippie parties, and pot smoking, sometimes accompanied by stiff, teeth-grinding rock music.

A new wave of anti-marijuana and anti-drug film shorts was being produced, often for showing in public schools, but here's betting seeing Sonny Bono in gold pajamas for a 1968 anti-pot short and Dragnet's ludicrous hippies inspired more kids to step one toke over the line than they scared off. Even more eye-rolling was the stentorian intonation of the narrator in 1969's "The Chemical Tomb," which proclaimed (in 1969, mind you), that "the age of bobby socks and ice cream sodas are gone. The Now Generation feels disenchanted with the world around them and have simply dropped out."

No shit, Sherlock. We had the Vietnam War body counts for news at dinner.

Cautionary tales were told in the lyrics of rock songs, though more and more they were celebratory of psychedelics. Even then, a shadow was spreading over the glorious haze in 1967. The Velvet Underground, as anti-hippie a band as existed at the time, came out with "Heroin." No apologies, no masking of the subject under alluring names, not with lyrics like "when I put a spike into my vein."

David Peel & the Lower East Side had a different, more up-front approach with their 1968 concept album, Have a Marijuana. "I like marijuana, you like marijuana, we like marijuana too!" the lyrics crowed. Written and performed in a singsong manner with nursery-school melodies, it was profoundly silly, predating Cheech & Chong by several years.

Steppenwolf was a band forthright about drugs, at least according to their songs. "Don't Step on the Grass, Sam" was John Kay's potent plea for marijuana decriminalization in 1968, but "The Pusher" and "Snowblind Friend" subsequently targeted heroin and cocaine abuse.

"Don't Step on the Grass, Sam" named names in declaring that "Misinformation Sam and Joe are feeding to the nation," composer Kay pointing the finger back at Uncle Sam and Sgt. Joe Friday from Dragnet. 1969's "The Pusher" and "Snowblind Friend" were both written by Hoyt Axton. The latter is particularly prescient since in 1971, coke was still considered a hip, nonaddictive, rich-kid drug. Axton's "The Pusher," on the other hand, sells heroin: "The dealer is a man with the love grass in his hand. Oh, but the pusher is a monster."

This generation needed its own media voice and got one in Rolling Stone, a bi-weekly newsprint publication dedicated to rock and subsequently, the marijuana culture. Long a supporter of grassroots organizations like the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, pot inundated its pages freely, promoted by major bands of the day. A vastly different publication from today's slick, teen-butt-kissing magazine, Rolling Stone was hip enough then to put Doug Sahm on the cover not once but twice.

Some Southern California and Texas bands experienced a closer relationship to the Mexican border, and for them, pot was serious stuff. Not just a doorway to enlightened thinking or an almost religious sacrament, but a tool. Okay, maybe for fun, too. But it wasn't fun for Freddy Fender, busted in 1960 for pot and sentenced to Louisiana's infamous Angola State Prison.

The damage was done. Pot had been lumped in with narcotics for decades by then and was treated accordingly by the law. Rock & roll arrests in the Sixties remained scandalous affairs: Donovan in 1966, the Redlands bust of the Rolling Stones the following year, and John Lennon making national headlines in 1968. The situation wasn't much better in Texas for the 13th Floor Elevators and Doug Sahm in 1966; Roky Erickson's second bust in 1968 led to his incarceration at Rusk State Hospital.

Dealer's Blues

The "violet crown" surrounding Austin in 1973 really was a purple haze of pot. The joint had been passed from rock to country, and now all the good marijuana songs were coming from the cowboys, cosmic and otherwise. Austin boasted its share of dope dealers sporting turquoise jewelry, custom Charlie Dunns, and Texas Hatters Stetsons. A trip to the old Oat Willie's on San Antonio Street for the latest Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers comic could result in a good weed connection.

It seemed as if the Armadillo was pumping out the coolest of music. Soap Creek was a newcomer on the scene, but the One Knite was an old-timer. Alexander's had blues, too, but was then way south of town. Ernie's Chicken Shack held court after hours, and Charlie's Playhouse was still open. Other nightstops included the Black Queen, La Cucaracha, Buffalo Gap, the Lamplight, Sit-n-Bull, the Gig, and Flight 505. Within a couple of years, Antone's opened down the street from the Ritz on Sixth Street. Clouds of smoke drifted everywhere from outside (and sometimes inside) the clubs.

At least that's the way it looked to me at 19. We were fearless pot smokers in those waning hippie daze, walking down the street, all lit up. Sitting on the front porch of South Austin houses that no longer exist, driving down the street with windows down, firing up outside the Capitol at night back when it was open 24 hours. Laying out half-naked at Hippie Hollow during the day, coughing and rolling and getting stoned and swimming.

That was a kind of Zen in those days, before skin-cancer scares. A frosty six-pack split between two, a couple of joints – one to levitate you when you got there and one après-swim – plus the unforgiving sun and the cold lake water. You could float in the water and fall in love just watching the flesh parade along the rocks. When the sun dropped in the sky, it was time to head home and shower before going to the clubs at night, more joints in tow and sunburned shoulders turned redder by the glow of embers during the break out back.

"Dope, Death & Dirty Dealing in Texas," shouted a Rolling Stone cover story in 1974 after a series of particularly gruesome murders of dope dealers in the area. Pot was commonly moved in Hefty bags, and no sight was more welcome than a furtive knock on the door from a friend clutching a black plastic sack who needed a place to break up a pound. Bored one weekend, I sat down with a pound we were holding for a friend, two packs of papers, and taught myself to roll good joints. "Another in a series of well-rolled joints," I'd announce when finished. I still say that. Meanwhile, the good guys, like Cleve Hattersley of Greezy Wheels, kept getting carted off to jail.

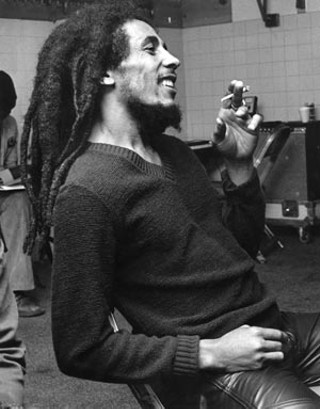

The Seventies brought with it a renewed interest in the old pot culture of the jazz era. Stash and Arhoolie records reissued albums like Tea Pad Songs and Pot, Spoon, Pipe and Jug, as well as collections like Copulatin' Blues, another likely activity post-puffing. At the movies, you could watch Doug Sahm buy pot from Kris Kristofferson in Cisco Pike or giggle to R. Crumb's animated Fritz the Cat. The decade also imported reggae music from Jamaica, the genre for which marijuana was the official high. The grinning face of Bob Marley, spliff in hand, spoke volumes.

Out in the clubs, Balcones Fault excavated the king of all pot songs, Stuff Smith's "If You're a Viper," in their sets, while Alvin Crow fiddled to the late D.K. Little's "Texas Kid's Retirement Run": "Well, he ain't stoppin' nowhere along the road. He's runnin' heavy with that overweight contraband gold. The Texas kid is makin' his retirement run." More to the point, "Stoned Faces Don't Lie," sang Doug Sahm.

The last days of the dream were played out in the Seventies. It was a pipe dream, to be sure, that the government might stop playing Feds and heads with pot smokers and deal with the tougher issues like returning Vietnam vets with massive drug habits and maybe an international connection to black-tar heroin. The devil was waiting around the corner, and the price to pay was beyond inflation.

"In 1976, I bet T.J. McFarland a pound of pot that marijuana would be legal in 10 years," recalls Ray Benson. "Pot was $300 a pound then. Time to collect 10 years later, and it was $2,000. He let me get away with a quarter-pound."

The last $10 ounce I bought was in April of 1978.

Return of the Stoner

The smoke cleared at the beginning of the Eighties in rock music. Lots of speed – too much of it – cocaine, heroin, then crack and other subdrugs shattered the veneer. The harder drugs suited the synth-heavy Eighties music but gave it an artificial heartbeat. You weren't living for that stuff; you were dying to do it.

The local blues revival in the Eighties kept smoking, but the initial wave of punk rock bands didn't. Speed was cheaper, not a hippie high like pot. That distinction was soon chopped up and snorted like so much powder, but there was a time when punks were not heavy into weed.

In one of the biggest films of the decade, 1982's Poltergeist featured a suburban mom and dad enjoying a little late-night puff before all hell breaks loose on the spectral plane. 1983's Scarface still captivates nearly 25 years later, because its cocaine excesses were so horrific. By then, pot smoking in movies had become accepted, even expected.

Pot got expensive, more so when a bad bust could cost a small fortune in legal fees, not to mention years of your life. Neither Austin guitarist Derek O'Brien nor percussionist Mambo John Treanor expected to be whacked as hard as they were with prison sentences when they were arrested in 1989 for growing pot.

Yet by the end of the Eighties, smoke signals were rising again, coming from two separate camps – rap and grunge. Both genres reshaped the pot mythology in the Nineties to suit their needs, while heavier bands like Corrosion of Conformity, Monster Magnet, and Texas' own Pantera began to emblazon their music and sometimes merchandise with marijuana. Austin's Richard Linklater directed the best film ever about high school with his 1993 ode to 1976, Dazed & Confused.

Gov't Mule covered Steppenwolf's "Don't Step on the Grass, Sam" for a second time on the 1995 Hempilation series for NORML. The compilation was a mixed baggie of artists from rappers 311 ("Who's Got the Herb?) and Ziggy Marley ("In the Flow") to Ian Moore's take on Muddy Waters' "Champagne and Reefer." Hempilation 2 in 1998 featured Willie Nelson's "Me and Paul." Oh yeah, the MC5's Wayne Kramer knocked out a version of "You're a Viper."

Marijuana laws continued to make folk heroes out of pot smokers. Clifford Antone took his second fall for the green stuff and did his time for it, but when Austin's Dan Del Santo ran into trouble selling pot to a Fed in West Virginia, he fled the country to Oaxaca, Mexico. A fine musician and DJ who was the progenitor of the term "world beat," Del Santo avoided a sentence but never returned, dying in exile in 2001.

The pot flag was still flying high for oldie bands like the Allman Brothers and the Grateful Dead and waved by newer bands like the Black Crowes and Snoop Dogg rolling down the street smoking indo and leading the pack.

Willie the Weeper

• November 2003: Toby Keith records "Weed With Willie" Willie also records a live version for his 2005 DVD Alive and Kickin' with Keith.

• July 2005: Willie's reggae album Countryman is released, with its marijuana-leafed cover replaced by a palm tree for big-box distribution.

• September 2006: Louisiana State Troopers stop Willie's bus outside St. Martinville. Marijuana and mushrooms are found.

• April 2007: Willie pleads guilty to a misdemeanor count of marijuana possession. He's fined about $1,000 and receives a suspended sentence of 60 days in jail. Nelson is also proscribed six months of unsupervised probation.

• Willie Nelson for president. ![]()