Life Worth Livin'

Uncle Tupelo Reissues: Not Just now, Forever

By Christopher Gray, Fri., April 4, 2003

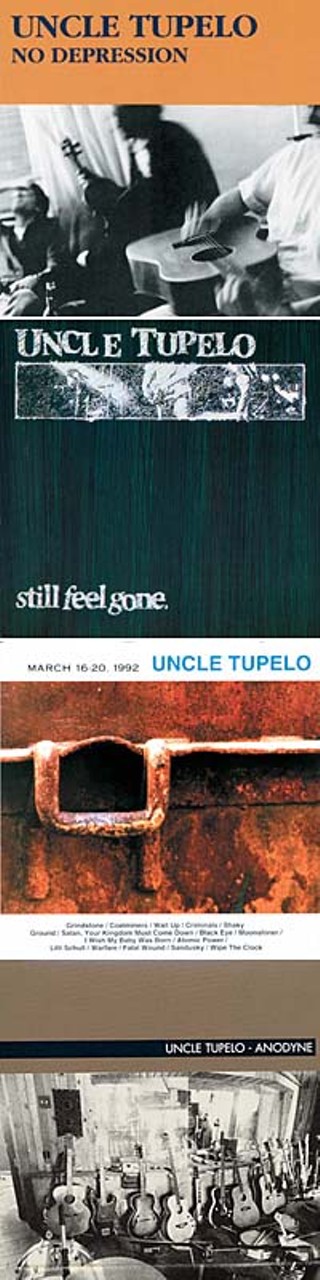

It doesn't seem possible that Uncle Tupelo has been gone for 10 years. Consider "Train," from the group's first album, 1990's No Depression. At 2:15am, Jeff Tweedy's aimless young hero is parked at a railroad crossing, waiting for a 97-car convoy of "troop trucks and tanks" to pass. He ponders his fate as "Turn, Turn, Turn" wafts from the stereo: "I'm 21 and scared as hell. ... I quit school and I'm healthy as a horse. ... Because of all that, I'd be the first one to die in a war."

Uncle Tupelo began like so many other bands, as three high school buddies who loved rock & roll a lot more than playing sports -- a lot more than anything, except possibly alcohol. They ended like so many other bands, too, in an unfortunate morass of hurt feelings and bruised egos. But over four scant albums, they built a legacy that continues reverberating to this day.

No Depression sprang fully formed from the trio's tribulations coming of age in Belleville, Ill., a decaying industrial town 20 miles southeast of St. Louis. The titles are self-explanatory -- "Factory Belt," "Whiskey Bottle," "Flatness" -- but it's in the music, too, outbursts of blind rage interspersed with patches of exhausted melancholy.

Optimism is in short supply, whether from Jay Farrar's clock-punchers in "Graveyard Shift" and "Factory Belt" or Tweedy's would-be draftee in "Train." About the only satisfaction available comes from a bottle, or in "Screen Door," from sitting around singing songs on the porch because there's nothing else to do (and they're out of beer money). "We're all looking for life worth livin'," sings Farrar. "That's why we drink ourselves to sleep." On "Whiskey Bottle," drinking trumps even religion, at least temporarily: "Whiskey bottle over Jesus, not forever, just for now."

Besides introducing the world to a pair of exceptional songwriters -- and Mike Heidorn's frenzied drumming, which often sounds like a factory belt gone berserk -- No Depression's greatness lies in how it applies punk rock's disaffected aesthetic to a class of people almost invisible by 1990: white, rural, blue-collar. For Uncle Tupelo, it's not about selling out; it's about getting out.

"'Well, not me,' you whisper," vows Tweedy on "Flatness." "This isn't where it ends" -- a rare admission that there might indeed be life beyond the screen door. What few flashes of hope there are on No Depression surface in its more acoustic moments, most notably the title track, as Farrar echoes the Carter Family's belief in a better world beyond this one. No Depression may be beloved for its brashness and raw vitality, but by the closing notes of the blazing "John Hardy," Uncle Tupelo had already exorcised those particular demons. Mostly, anyway.

Still Feel Gone, from 1991, complicates things as Farrar and Tweedy flesh out the personas they set up on the previous album: Farrar as the hard-bitten friend of the workin' man, Tweedy as the good-natured yet pragmatic romantic. Where the listless torpor of No Depression is marked by screaming guitars and flailing drums, Still Feel Gone's broadened musical palette -- mandolin, accordion, piano, organ, harmonica -- makes it at once rootsier and further removed from the trio's punky origins.

Tweedy-sung numbers like "Nothing" and "D. Boon" maintain the breakneck pace of No Depression, but the more sedate "Cold Shoulder" and "If That's Alright" hint at the songwriter he became a decade later on Wilco's Yankee Hotel Foxtrot: contemplative, resigned, fatalistic. "Gun," though, turns the observational acumen of "Train" and "Flatness" inward, resulting in a rough-hewn pop gem that manages to inject a note of humor into the unusually dour Tupelo canon ("Falling out the window ...").

Meanwhile, Farrar keeps hoping for something better somewhere down the line, and turns in some of his most articulate work: the steady, assured "Looking for a Way Out"; the inquisitively hopeful "Still Be Around"; and the plainspoken, Dylanesque "True to Life." Some of the SST-inspired feistiness of No Depression's "Outdone" lives on in "Postcard," albeit sandwiched between ruminative layers of steel and acoustic guitar. His embrace of earthier textures points directly to where Tupelo was headed next.

Produced by R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck (and coinciding with that group's own "acoustic" phase spanning Out of Time and Automatic for the People), 1992's March 16-20, 1992 delves even further into the shadowy corners of Appalachian-derived music. The tone is biblical, Old Testament-style, from the covers of the Louvin Brothers' "Atomic Power" and the traditional "Satan, Your Kingdom Must Come Down" to Farrar's musing about the "clockwork of destruction" on opener "Grindstone."

Whereas their first two albums are almost exclusively autobiographical, on March 16-20, Uncle Tupelo regresses into its members' (imagined) past lives. Farrar becomes a labor advocate ("Coalminers"), bootlegger ("Moonshiner"), and cold-blooded killer ("Lilli Schull"). Tweedy inhabits a man imagining killing his pregnant wife on "I Wish My Baby Was Born," and the lovesick insomniac of "Wait Up." On the mournful "Fatal Wound," the cold world outside is still warmer than his lover's gaze.

The crux of March 16-20 is the fire-and-brimstone trilogy of "Atomic Power," "Lilli Schull," and "Warfare." As mandolins chime and fiddles swoon, the first suggests the best way to survive a nuclear attack is to trust in Jesus. "Lilli Schull" is a despondent tale, accentuated by a forlorn Dobro, of a condemned murderer begging the Lord to show him a mercy he couldn't give his victim. "Warfare" finds Tweedy asking God's blessings on "those good old shouting Methodists, those praying Baptists, too" as he also prepares to meet his final reward.

Uncle Tupelo's fixation with the hereafter proved prescient; once March 16-20 was released, they weren't long for this world. Heidorn, whose role was already curtailed on the all-acoustic album, subsequently left to start a family. The band recruited drummer Ken Coomer and part-time players Max Johnston (various strings) and John Stirrat (bass), and convened at Austin's Cedar Creek Studios to record what would become their swan song, 1993's Anodyne.

In retrospect, it's hard not to see what was coming; Anodyne makes the group's dissolution seem inevitable. The album begins with Farrar singing "bury the hatchets we find" on "Slate" and closes with his lament "no more, no more will I see you" on "Steal the Crumbs." In between, though -- what a way to go.

"Slate" is a slow-cooking prelude to the joyous fiddle of "Acuff-Rose," an ode to the famed Nashville publishing house and the belief that the right song can block out everything that's falling apart. Next is the swaggering "The Long Cut," which, ironically, touts perseverance in the face of long odds. If only they'd taken their own advice.

And it gets better. Doug Sahm shows up for a gleeful romp through his "Give Back the Key to My Heart," and Farrar finally returns to fiery No Depression form on "Chickamauga," where the foreshadowing flies fast and furious in the line "the time is right for getting out while we still can." Tweedy's "New Madrid" is a bouncy, banjo-driven ode to country boys and city girls that smiles in the face of "impending disaster."

Anodyne, and thus Uncle Tupelo's career, climaxes over the next two songs. Lloyd Maines' glorious pedal steel can't quite assuage the lurking resentments and regrets of the title cut, where Farrar acknowledges "it's a quarter past the end." Tweedy's "We've Been Had," by contrast, is a boisterous, Stonesy nugget that yanks the blindfold from even his idealistic eyes: "Every star that hides on the back of the bus is just waiting for his cover to be blown."

By that point, Uncle Tupelo's cover was blown and they knew it. Almost exactly a year after recording Anodyne, the band split in June 1994, as childhood friends Tweedy and Farrar were headed down increasingly irreconcilable musical paths. Today, acts like the Gourds, Ryan Adams, Calexico, and Grand Champeen keep the torch lit, as thousands more each year discover what made the boys from Belleville so special. In short, it's a line from Still Feel Gone's "Nothing":

"Don't call it nothing. It might be all ... you'll ever have." ![]()

On April 15, Columbia/Legacy is reissuing expanded and remastered versions of Uncle Tupelo's No Depression, Still Feel Gone, and March 16-20, 1992. An expanded and remastered Anodyne is out now on Sire/Rhino.