The Memory of Music

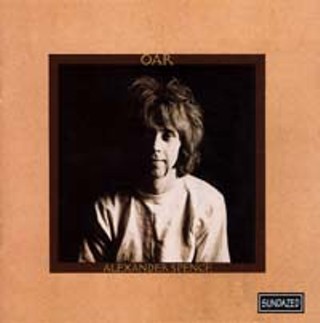

Skip Spence's Oar

By Louis Black, Fri., Dec. 17, 1999

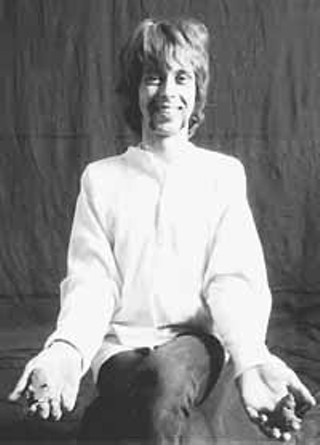

In order to tell this story, I have to start with me lying in a bathtub, in a house on Hollywood east of I-35, in the very early Eighties. The water has mellowed to lukewarm. My head is laid back, my eyes closed, my body buzzing. On the record player, playing over and over again is Skip Spence's Oar. The blinds are closed. There is a sheet hung over one window, a blanket over the other. There is no reason for the sun ever to enter this house. I've been in the bath since 6am. No one else is home. It is past dawn. One side of Oar keeps repeating. The record ends, and the clicking sound of the arm and needle going back to the start of the record repeats once again. Guitar strumming, then a voice singing part pop song, part chant.

Little hands clapping, children are laughing. Little hands clapping, all over the world.

It's not just the tone, it's the voice, coming from somewhere far away and deep inside. If there were a pop station on Desolation Row, this would be the hit. It's an album that never sold and I can't imagine it boasts much of a cult following.

Now, unexpectedly, thanks to the ever-amazing Bill Bentley (see accompanying article), Skip Spence is being rediscovered. Not only has Oar been reissued, but Bentley's masterminded a tribute to it, More Oar. This is not a review of either, however. This is the story of my adventure with Oar, how I ended up in that house, lying in that tub, listening to that album over and over.

Imagine a musician who was instrumental in both Nirvana and Soundgarden and who passed through Pearl Jam briefly before inspiring Alice in Chains and you have a rough idea of Skip Spence's importance to the San Francisco music scene of the Sixties. The scene, which, though in retrospect seems more quaint than potent, had an extraordinary effect on rock music and on the country. Not just musically, but in terms of culture and lifestyle. In the City by the Bay, these forces were integrated, and the Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, Big Brother & the Holding Company, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and Sopwith Camel not only made the music, they lived the life. Marty Balin came upon Spence in a bar, loved the way he looked, went up to him and said, "Hey, man, you're my new drummer." Guitarist Spence, who had played with a nascent Quicksilver Messenger Service, took the drumsticks handed him and joined Balin's band, Jefferson Airplane. The first album, The Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, featured lead singer Toby Signe Anderson, who would soon leave to be replaced by Grace Slick. On the album, Spence not only drummed, he co-wrote "Blues From an Airplane." The first single the group released was Spence's song "My Best Friend."

Ah you're my best friend/And I love you so well/ 'til the end of time/ You won't see me/Ah you're my best friend/ And I see you it seems/ Now I can see it/I've fallen into your love stream/I follow your dreams/Do you know what I mean, yeah?/I'll follow you wherever time will take you.

Spence was fired from the Airplane by the time the song appeared on their classic second album Surrealistic Pillow, released in 1967.

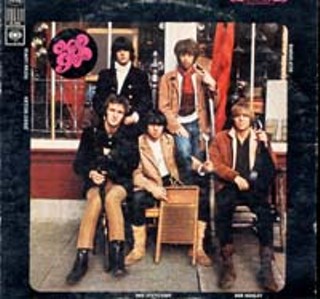

In August of that year, Moby Grape came together. The lineup consisted of three guitarists -- Peter Lewis, Jerry Miller, and Skip Spence -- and a rhythm section of bassist Bob Mosley and drummer Don Stevenson. All five musicians were exceptional songwriters, and together they made a landmark, near-perfect debut, 1967's Moby Grape. Perhaps even more stunning was the impressive failure of the band in its wake, the album and band being overhyped to the extreme by its label, Columbia Records; the five went from musicians to rock stars without the benefit of fans.

They threw a ridiculous release party in San Francisco and then released five singles at once to showcase the band's five writers. Spence contributed a few numbers to Moby Grape, including the amazing "Indifference."

What a difference a day has made/What a difference a day has made/What a difference and none of the same --

Despite the quality of the music, the promotional strategy proved disastrous, not only alienating the ever more anti-hype political audience, but turning the band against itself. Both Moby Grape and the band's next album, Wow, performed respectably, though not outstandingly, but the band wasn't able to function in the wake of raised expectations. Within six months, everything fell apart, and the tightest band in San Francisco would stumble through a few more albums over the years, but never come close to the debut.

They struggled along, playing mostly lame gigs alternating with much more inspired moments until some time in 1968. Then one night, whacked on whatever, Spence took an axe to the hotel room door of bandmate Don Stevenson. He ended up in the Bellevue psychiatric prison ward for six months. The other four continued on as Moby Grape.

After being released, Spence got a small advance from Columbia -- no more than $1,000. He spent some of it on a motorcycle and drove straight to Nashville. There, with the rest of the money, he recorded Oar between December 3 and December 12, 1968, at the Columbia Recording Studios. What emerged is the often-harrowing Oar, a revolutionary lo-fi imitation of Harry Smith and Lomax collection-type vintage 78s, full of demented pop songs. The album was released and disappeared. Spence essentially disappeared with it, though he's credited with helping start the Doobie Brothers and appeared in various Moby Grape reunions over the years.

Spence was only 22 when he made Oar, but he was already a veteran rock musician and songwriter. Unlike most lo-fi revolutionaries, with Oar, Spence was not making a flying-under-the-radar attempt to scale the industry's walls. Oar's minimalist sound and dirge-like overtones were the sounds Spence was hearing in his head when he made the record. What really drives the album is his songwriting skills. The beautifully crafted pieces often work alone, but all sound as though they're fragments of a larger work.

Over time, the sparkle of Spence's legacy diminished. Not only was Oar a total failure, but time hasn't been kind to any of the Bay Area bands except, maybe, Janis Joplin (though certainly not Big Brother & the Holding Company) and the Grateful Dead. The once vibrant, influential, and in every way remarkable music now often seems dull and distant. Although the community that knew and nurtured Spence cherished him, his name all but disappeared.

Enter the remarkable Bill Bentley, ex-Austinite, ex-music journalist, Warner Bros. VP of publicity, and deeply committed music fan. Gathering such longtime Moby Grape fans as Robert Plant and the Durocs, as well as convincing others such as Tom Waits, Bentley produced a tribute album to Oar. Spence died just as More Oar was scheduled to be released this past spring, coinciding with the release of Oar on CD for the first time.

Tribute albums are strange beasts. I find the emotional experience of listening to an album resonates greater than the music itself. Buying a CD of some treasured work, only to have the tracks rearranged from the original LP release that I've committed to memory, is unnerving. Some albums never work as well again. I have a recording of the Band's Music From Big Pink that's re-sequenced, and thus somehow, always, falls flat. Once I prized these moments as songs and as music that was alive and changing, but now these are memories -- they have a different meaning. I no longer want them to move so much.

And yet, if ever an album invited reinvention, it is Oar. Almost a demo tape as much as it is a finished work, it's a road map back to the kind of rock Spence once made. Oar swims in its own depressions, not just lyrically and musically, but in every emphasis of every breath. It also thrives. These songs represent a new folk music, and much of their power is in their very invention. A generation before American music would be reclaimed from the ornate by the punk and lo-fi revolutions, Spence was already there.

Oar is OAR to me. It is a sinking house and a sinking self. Even on CD, I find I miss the thin sound and scratchiness of my vinyl copy. More Oar is jarring. It's like a distorted memory. Which is my review, not yours, and I might be the least-qualified person around here to review it. Surprisingly, I like More Oar best when it's least faithful to the album, when it treats the songs not as movements of a symphony, but independent works. Robert Plant's "Little Hands" and surprisingly, "Lawrence of Euphoria" by SF's Ophelias reminds us that Oar was the culmination of a body of songwriting. Most of Spence's output was presented in a rock context; listen to his songs on the Airplane Takes Off, Moby Grape, or even later Grape material such as "Motorcycle Irene" on Wow or "Seeing" from Moby Grape 69. The faithful renditions illustrate the emotional complexity and textural richness of Oar. They are great fun to listen to, but watching artists work out on Spence's material in different directions is revealing.

Using a phase shifter, playing all the instruments, screwing around in the studio with the very texture of the sound, Skip Spence recorded a masterpiece. But who knew? When I bought Oar, it was because Spence was a cult figure who had been in two of my favorite bands. At first, I didn't much like it or get it. Time passed.

A decade after I bought it,I'm listening to Oar, lying in the tub. Awake for five days, wired and charged, I've downed most of the half gallon of vodka tonic that I always keep in the refrigerator. Lying there, I know I won't be able to sleep for hours. I'm listening to a tired, pained voice over a simply played guitar.

Weighed down by possessions, weighed down by the gun. Waited down by the river, for you to come.

It's a subversive blues song, like a scratchy 78 by Pinetop Smith, according to producer David Rubinson in the liner notes to the Oar CD -- except it's a punk Pinetop Smith. My nerve endings are clearly exposed, waving in the air like tiny tendrils. Most music would be dangerous now. I'm floating off into space, terrified of being jarred. In harmony with my disintegration is the melodic madness of Oar. This album is the memory of music, the silhouette of music. It is the shadow of Sixties Top 40, the very shape shifting as the light moves. It is as much idea as tonal, as much emotion as sonic energy. It is self-contained, unique and historic, and as much as it fills some spaces, it recoils from others. This music is welcome. It is the end of hope.

Ironically, my story begins in a time of too much hope when all was possible -- in 1968, in the snack bar of a Boston University dorm. Calling it a snack bar is flattering this university's attempt at congeniality, a few tables, chips, candy bars, and wrapped pastries with hot dogs and hamburgers available. But there is a jukebox. This guy I met taking some freshman orientation test, when we both started laughing aloud, is hanging with me checking out the musical selection.

We see "Pretty Boy Floyd" by the Byrds. We were both disappointed in the last Byrds album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo -- it wasn't the folk-psychedelic rock we'd come to expect from the group. We play the song. Hey, this is good. We go back to Alan's room to listen to the album. It's great. A love of country music and a friendship began. Moby Grape was his favorite album.

This was a time of discovery. Media coverage of rock was very different. There was not only no MTV, but rock groups were rarely guests on network shows, and there were only network shows. There was Rolling Stone, which offered news and great reviews, but most of what we learned we discovered at the record store. We haunted the bins, looking for new music, scrutinizing the performer and especially, songwriter credits. This was our library, LP jackets were our literature, the music made meaning. Buying a new album was a big deal. We'd all gather to listen to it. Usually the listening would involve a stack of new albums with all present having purchased a few. We would spend all day listening. Those were good days.

We believed the music was going to change the world. We really did believe, no matter how ridiculous it sounds, that a new American revolution was in the offing. We thought things couldn't go on as they had and that we should take over, culturally as well as politically. We thought that we could change the country and the country could change the world. Driving this change, more than politics, was music. It was where our philosophy and ideology were laid out, and nowhere more ferociously than in San Francisco.

Ours was the counterculture, though we hated the term. We thought of ourselves as freaks, not hippies. Hippies were too peace-and-flowers, lovey-dovey Donovanesque weirdos. We wanted change -- social, racial, and economic justice -- and we didn't want to participate in the dominant culture. Mostly we sat around, listened to music, went to demonstrations, occupied buildings, talked politics endlessly, and thought of ways to meet women.

We were suspicious of the establishment politicians and equally suspicious of the SDS radicals who claimed to speak for us. But we believed in the music. We thought this change wouldn't be a base political change, not merely a shift in voting patterns, but a profound lifestyle change. A brave new world, and the music would drive it. We believed the music was the message, the music was the revolution, the music was change.

Imagine sitting around a room with some deadly serious lesbian Weather Women as they discussed Dylan's New Morning for hours. These people were out to change the world, but they spent the night arguing over the meaning in Dylan's lyrics (for, arguably, his most lightweight album). The Weathermen, of course, had taken their name from a Dylan song ("It doesn't take a weatherman to know which way the wind blows"), but still. Except it was Dylan and the music was that important. In a way you can't imagine, the San Francisco bands were a crucial part of what was happening.

The importance of the Jefferson Airplane, in particular, can not be underestimated. They were the Beatles of the San Francisco sound, and the Grateful Dead were the Stones. At a certain point in time, everyone owned a copy of Surrealistic Pillow. Everyone. As the Sixties became more political, so did the Airplane.

Their music was anthemic rock by way of every American musical form from bluegrass and blues to folk and country & western. Coming out of the Fifties folk/American music revival, most of these musicians cut their teeth in dozens of different kinds of acoustic bands. The Grape were part of this era, though not as politically subversive as the Airplane or as culturally subversive as the Dead. Their astonishing proficiency made that first album stunning.

Today, after progressive country, punk, lo-fi, New Wave, alternative rock, alt.country, and whatever, every fresh idea that came out of San Francisco in the late Sixties seems like a tired cliché. When a dozen duos have matched the soaring power of Slick and Balin singing together, most notably John Doe and Exene Cervenka in X, the thrill of first hearing this music can't be reproduced.

When the CD revolution began, I got the Airplane, Grape, and other SF bands on CD, and after probably a decade of not listening to them, I listened. At first, I was thrilled. Unfortunately, repeated listening revealed that much of this was the pleasurable memories of a pretty wonderful time. A lot of the music didn't hold up. This sobered me. Surrealistic Pillow and Moby Grape rang fresh, but After Bathing at Baxter's or Quicksilver Messenger Service had lost their energy. Even once-inspiring works disappointed, like the Airplane album Volunteers ("We are all outlaws in the eyes of America/In order to survive we steal cheat lie forge fuck hide and deal/ We are obscene hideous lawless dirty violent/ And we are very proud of ourselves"). What must Sopwith Camel or Country Joe & the Fish sound like to fresh ears?

Alan and I got an apartment. Listening went on all the time, alone, in groups, late into the night, early into the morning. We listened to new albums, listened to old albums. Friends brought records over, and we usually traveled with records. We listened to the Grape and the Airplane a lot (the Dead were best live). Somewhere in there, 1968 or '69, I bought Oar. I listened to it some, but not a lot.

In some configuration, with maybe three original members, the Grape came to Boston and played the Psychedelic Supermarket. Alan went and was crushed. They sucked. He loved precision playing and cherished them for their superb craftsmanship. It wasn't there.

In 1970 I moved toVermont. There I found myself listening to Oar more and more. In the long, dark snowbound night, sitting at my desk writing, I'd let the album play over and over.

I'm Lawrence of Euphoria /Share your tent/Pay your rent/It's worth every single cent /I'm Lawrence from Euphoria/You rise from the deep/come in to sleep/No more will you weep.

Oar was an album you almost never played for friends. It was best savored alone. The rough wooden walls of the farmhouse bedroom were the perfect fabric to frame the sounds of the album.

Years later, I moved to Austin, where everything went spectacularly well for awhile. Then the center collapsed, or more accurately, I collapsed it. In many ways, despair is the most successful drug. Henry Miller wrote, "Once you've given up hope, all else follows with dead certainty, even in the midst of chaos." As a friend pointed out, "If you're depressed and full of despair, at least you're probably right about the way your life is going to go." In this time of need, Oar was literally played over and over.

Broken heart be lovely/broken on the ground/A knife stuck in the ribs of me/Would better than be found/Hanging tree blowing gently/A noose would be ignored/Than to stand upon the receiving end/Of the right hand of the Lord.

Read those lyrics. They make little sense, until you hear them in Spence's song, where their poetry is overwhelming. Traveling to the heart of despair, with a guide who well knew the way, helped save my life. Getting these albums on CD was a treat just as it was unreal. Oar is now just music and not my life. But once it was. ![]()