Music of the Spheres

Sinatra in the Sahara

By David Lynch, Fri., July 9, 1999

|

|

A symbol of this incongruity is Casablanca's breathtaking Grande Mosquée Hassan II, one of the world's largest religious monuments. It took over 6,000 Moroccan craftsmen working day and night over five years to complete the religious structure. Its interior is so massive, large enough to hold over 25,000 worshippers, that St. Peter's Basilica in Rome could literally fit inside. The nearly 700-foot minaret shoots a laser that can be seen some 25 miles out to sea. Impressive to say the least, but enough to warrant its equally huge cost of nearly $1 billion? This price tag is even more conspicuous as nearly all construction costs were paid by public subscription, amazing in a country where daily workers are lucky to make $3 a day.

From the 10th century until the French invasion in 1830, Fez was the center of Moroccan culture, trade, religion, and politics. Moroccan influence during that period spanned broadly from Senegal to Spain. Europeans who visited Fez in the Middle Ages were awed by the city's advanced developments in the arts, medicine, mathematics, and philosophy. Even today, while Casablanca and the country's capital, Rabat, enjoy more political clout, not much happens in Morocco that doesn't happen in Fez too. The city, founded by a Sufi saint, is the cultural weather vane of Morocco, a place where Muslims, Jews, and Christians have coexisted for centuries. It might seem strange, then, that the Fez Festival might not exist today had it not been for Iraq's invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

With the ensuing Persian Gulf War in 1991, tensions between the Middle East and the West came to a boil, then-President Bush calling for a "holy war" to counteract Saddam Hussein's ego march. Fez-born, French-schooled anthropologist Dr. Faouzi Skali, founder and director general of the Festival, wanted to counteract this disturbing trend, explains Joel Davis of Sounds True Records, a Colorado-based label, which has released two albums' worth of Fez Festival music.

"The intention of the festival," says Davis, "was to show the world a more realistic image of the Middle East: a relatively peaceful region with deep spiritual roots, populated by people of many different faiths who have a history of living harmoniously with each other."

Dr. Skali's initial idea was to organize a film festival called "Desert Colloquium" to counteract the violence of the so-called "Desert Storm" military campaign. The festival included music, but because music was more efficient at breaking down cultural barriers than film, the organization chose to focus on sound rather than sight. More importantly perhaps, is the dominant notion that runs through both the promotion and appreciation of sacred music, as well as the "world music" subset from which it is drawn: the belief that music transcends cultural, linguistic, social, geographical, and temporal boundaries. To many, music is indeed the universal language.

|

|

While symbolically reaching out to the world, the Fez Festival quickly established itself as a high-class event. Unlike most festivals that hawk every imaginable product and/or service -- where logo placement looms like Big Brother's propaganda -- today's Fez Festival offers no souvenirs, with the exception of a program. Even T-shirts are absent. In addition to the king, the event is sponsored by Moroccan banks and television networks, but even then festival participants aren't bombarded with commercialism. Instead, they pay for their privilege: a pass to the festival's week-long programming of concerts and presentations costs about $250 -- no small amount for Euro-Americans, especially given the travel costs. For native Moroccans, however -- those with jobs (unemployment in the country hovers in the 20% range) -- the price is stratospheric, the equivalent to three months of paychecks. It is a festival for tourists from affluent countries, and for rich Moroccans.

Funky Old Medina

Fez possesses one of the most impressive examples of living history in the world, the city's oldest quarter being very much like it was 10 centuries ago. Narrow serpentine alleys flow with beasts of burden, their backs loaded with every imaginable payload: propane tanks, fresh fruit, textiles, and people, all going to every imaginable destination -- restaurants, mosques, craft shops, and homes. If it weren't for the occasional satellite dish, modern music blaring from store fronts, and pasty, gawking tourists, there would be little to mark the 20th century.

The medina is still surrounded by ancient walls, which are themselves impressive. Living vertical monuments to Fez's history, they are pockmarked by weather, wars, and tenacious swift and swallow birds who have, over the centuries, pecked out small nests within the formidable stone walls. These little bird caves give the milky-red ramparts and thick walls their Swiss cheese countenance. It's these massive, age-old stone walls that surround the festival's two primary venues, both unshielded from the weather's capriciousness. Built in 1308 and holding nearly 1,000, Bab Makina is named after the gate that opens into a fortified esplanade. The smaller venue, known simply as Batha ("bah-tah"), holds a few hundred fans at most, with both the stage and the audience situated between a massive, octopus-like tree and the walls of the courtyard to the Musée du Batha, a former palace and now a museum of Moroccan arts.

Discantus, a French female group, don't get to perform at either of these two inspiring venues, but no one in the seven-member a cappella group, who interpret feminine-oriented Gregorian chants from the ninth century onward, are complaining. They hit the jackpot of venue picks, a stage directly beneath the Triumphal Arch at the ancient Roman ruins of Volubilis. While challenging physically as a stage setting, the ruins of Volubilis are magnetic, justifying their use as the location for many key scenes in Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ. Walking around the ruins, it's easy to see why Scorsese chose to film here. The site retains an ineffable magic, partly from its ensconced position where the mountains open up into a fertile valley, but also because of the numerous grand mosaics. And even though these pointillistic tile works are completely exposed to the elements, they are well intact, vivid time capsules to the historical weight of the place.

Volubilis is symbolic for other reasons. While both world and sacred music express a searching -- be it for spiritual elevation or merely for something other than the stock verse-chorus-verse and 4/4 time signature -- this can also be expressed backward, through time. A recent mailing by the venerable New York indie label Lyrichord Discs, for instance, features their world and "early music" catalogs containing titles such as Indian Music for Meditation and Love and Persian Love Songs and Mystic Chants. The "early music" category, like world music, is a vague catch-all term broad enough to fit many disparate styles, and counts among its chorus Guillaume Dufay of the Dufay Collective, who along with Discantus was another early music group performing at the Fez Festival.

Don't assume, however, that this music is only for the initiated, the historically fixated, or bespectacled academics. Music written by spiritual guide Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) enjoys brisk international sales, with the near legendary Chant album, medieval incantations similar to those in Discantus' set at Volubilis, having sold well over 5 million copies worldwide. Naturally, to the untrained ear, "early music" might sound more or less the same as other kinds of "world" music, but the majority of the Fez Festival's lineup was nothing if not contemporary in nature.

|

|

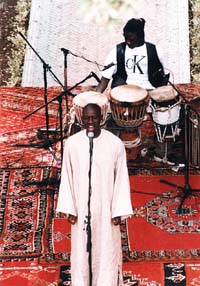

Bringing in one of the larger crowds was the Syrian bionic bard, Sabah Fakhri. He is so popular in Morocco that people traveled for hours from Casablanca and Tangier to attend his set. Fakhri's reputation is earned in part for his remarkable endurance. He holds the Guinness Book of World Records' mark for the longest performance, 10 and a half hours. Another great voice from the Middle East, although less secular (and therefore wisely on the smaller Batha stage), was Upper Egypt's Sheikh Yasin. In one of the most transcendent concerts of the week, Yasin's set slowly increased in emotional intensity, so gradual that the two percussionists with him didn't start playing until the hour mark. Accompanied by lute, violin, and flute, Yasin created a bridge, however brief, with the divine.

Adding both political perspective and soulful sounds was living legend Miriam Makeba. In an early week presentation, she told of her fascinating life progression -- from a house servant for rich white employers into an international music star. With jazz great Randy Weston sitting behind her on piano, Makeba spoke of her exile from her homeland of South Africa due to her singing the truth about apartheid. For many years, Makeba lived as something of a nomad, residing in countries that would sponsor her (Belgium, Guinea, United States), until she was able to return to South Africa in 1990. Putting her personal life into tear-welling South African sacred music, Makeba proved that she is as vital and influential as ever.

The finale of the week also turned out to be the Fez Festival's supreme highlight: veteran gospel outfit the Blind Boys of Alabama holding service on the Bab Makina stage. Gospel is huge at the festival, each year bringing in the largest crowds, and as always, the Blind Boys were on fire, the entire group pumping out holy sounds that had the fans shaking the aluminum-framed festival seating. It was during the lengthy jubilee-meltdown outro of "Lord Remember Me" when it became obvious that things were heating up. Literally. The band actually sucked so much power from the soundboard that the LED meters dimmed with each downbeat, prompting the recording engineer to direly predict "we could go down any minute."

The crowd of young, mostly mixed Moroccans ate it up. Dancing in the aisles and mouthing the words to the encore, "Oh Happy Day," the energetic fans freaked out festival organizers so much that Fez City Police were called in to look imposing. Why are kids from Morocco so into gospel music from America? There are a myriad of possible explanations: an exploration of pre-modern religious wisdom, a spiritual salve to the crush of technological advancements, fin de siecle soul searching?

Like most festivals that have humble but significant beginnings, frequent attendees of the Fez Festival often bemoan the fact that each year things get more and more crowded. This is certainly the case in Fez, as each year the elbow room quotient decreases, but more than merely another exotic tourist locale, the festival's increasing popularity signifies the growing interest in both sacred music and so-called world music.

The Empress of Russia

|

|

Joining Jones that night were folks from a few of the more adventurous record labels, such as EarthWorks and Triple Earth. The like-minded group met to discuss ways of getting their product more widely distributed, via radio play and record store promotions. They needed a term short enough to get through to slow-witted promotional types, and yet vague enough to appeal to short-attention-span journalists.

"We couldn't get our records in the shops," recalls Jones, "so we decided to come up with this term that we thought journalists could write about, and then record stores would be able to stock our vinyl. We were struggling with independent distribution, and we just wanted to be taken seriously. Before then, there were no ethnic record bins in stores -- they didn't exist.

"We were discussing the term 'global beat,' but Indian classical music is hardly global beat. So we eventually we came up with what I have to say is the blandest term, 'world music.'"

And vague it was -- is. Strictly speaking, everything is world music. Yet as a marketing term, the tag was designed to describe a particular type of music. Just as anthropology has traditionally been the study by Westerners of tribal cultures under colonial rule, so too has world music been primarily non-European/American music packaged for Euro-American consumption. Does that mean West Virginian bluegrass is "world music" to a Nigerian? Admittedly, most music genre monikers are vague. The important thing to keep in mind is that people act as if it applies to a certain type of music.

Considering that a group of small labels managers in London coined the term "world music" over a few pints of beer, classifying non-Western music under such a general banner seems the height of folly. For Jones and her compadres, however, the strategy, which included pooling their resources to hire a press officer to herald the term, eventually worked. Especially for Real World.

Of course Jones admits that Real World's co-founder, Peter Gabriel, had something to do with the label's success. But even without a marquee name like Gabriel's, odds are Real World would have done well anyway. Gabriel's exposure might get folks to buy one CD, but the label's success -- like that of other world music indies like Axiom, Shanachie, and even local label Chocolate -- is fueled more by their artistic vision (to which Gabriel contributes) than just mere name recognition.

"We never set ourselves up to be some ethnomusicologically correct record label," says Jones. "We don't say that we are the ultimate world music label that releases music from all over the world. We've been driven by our personal love of particular projects."

This year, Real World is celebrating its 10th anniversary, and indeed the decade has been kind to the London-based label. Since 1989, Real World has released an average of eight albums a year, selling nearly four million albums worldwide in the process. Some of the label's best sellers (Geoffrey Oryema, Sheila Chandra, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, and Afro-Celt Sound System) have sold well over 200,000 units each. These numbers may not sound significant in a world of enormo-corporation labels, but this steady success has served the label well: Their 1989 catalog is still selling.

Everyone's a Buddhist

So who's buying releases by Real World, and other comparable labels like Hannibal, Putumayo, and World Circuit? Why has the interest in world music experienced such a rebirth in the last 10-15 years? Iconoclastic producer Bill Laswell had a answer when interviewed last year. His typically frank comments frame the issue well.

"It's people learning, expanding, and looking for alternatives," explained Laswell. "This week everyone's a Buddhist. Next week everyone's reading Deepak Chopra; Madonna, Ray of Light. People are looking for alternative lifestyles. They know there's something wrong with what we're taught, what we eat, how we live, and because communication is putting people in closer proximity, and everyone's learning, I think it's an incredibly positive time. It'll be manipulated to death and the business will take over and kill it I'm sure, but it's a moment when people are fighting oppressive restraint."

Laswell's reference to Madonna's last album, Ray of Light, is of course, case in point. If the material girl of the Eighties incorporates components of Indian spirituality and Jewish mysticism, via the Kabbala, into her public persona, then the spiritual is a hot commodity. By why the current interest in spirituality? Why now?

"I think the generational thing has a lot to do with it," says Zeyba Rahman. Like Jones, Rahman is well positioned to describe the trend. Rahman is the board chair of the World Music Institute, a multifaceted cultural arts organization in New York. Rahman describes the venerable institution's mission and goals.

"Essentially, the Institute believes that culture is the glue that binds world communities together," explains Rahman. "And focusing on regions that are understressed economically or politically keeps their cultural traditions alive."

A prime example of such advocacy is the Institute's sponsorship of the recent Gypsy Caravan tour. The tour brought together six different Gypsy musical and dance groups from India to Spain, stopping in Austin this spring for one of their select North American dates. For Rahman, the increased interest in world music, as well as its spiritual subset, is due to the average age of the population's mass.

"Its the baby boomers for one thing," she says matter-of-factly. "They're such a huge mass of people. They were turning the world upside down when they were teenagers. And as they get older they're searching, their tastes developed towards another point."

In addition to generational reasons, there are at least two other probable causes for world and sacred music's recent success: technology and the millennium. Interest in music from around the world is certainly not new. From Ravi Shankar's sold-out shows of the Sixties (and still today), to Bob Marley's sold-out shows of the Seventies, there has always been an interest in music from other points on the map. But it's different now.

|

|

It was a gradual process, but today bands can make high-quality recordings for a fraction of the price from 20 years ago. The trend also opened up lines of distribution: Until the early part of this decade, one had to go to an Indian or Pakistani video store in cities like Chicago or Houston to buy cassettes of world music's shining star, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. Now, his CDs can be purchased at the Best Buy in Biloxi. With new digitized sound formats like MP3, QuickTime 4, and DVD, technology will make the music of the world -- New Zealand punk or Chinese orchestra music -- even easier to hear and obtain.

As with any significant stylistic trend, there are both desirable and undesirable results. On the positive side, music that may never have reached the light of day is now being released, such as Ireland's sean nos singer Larla Lionáird, or the Beatles of Morocco, Nass El Ghiwane. This trend can also fuel cross-pollination projects, like in 1990 when Real World's Massive Attack remixed the title track of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan's Mustt Mustt. This was well before the electronica outfit had released their first album, Blue Lines, in 1991. The remix is a blend of phat back beats and ethereally potent vocals, and it works in spite of the odd pairing.

As far as riding the trendiness of world music, you can count on the media to push the concept to its absurd end. At its most watered-down level, world music is another marketing gimmick used to promote well weathered pop stars. An example is a recent advertisement in the International Herald, a global circulation English-language newspaper, for CNN's show World Beat. Next to well-known Afro-pop stars are pictures of Elton John, Gene Simmons of Kiss, and Sheryl Crow. Here, world beat is not an avenue to explore the planet's platters; it's an excuse to ram hegemonic banal pop down the throats of so-called "developing world markets."

Due no doubt to the success of the Fez Sacred Music Festival, new sacred world music festivals are either planned or underway. This summer, Music Village, a London-based music organization, will hold a multi-faith, international music festival called "Sacred Voices." The biggest sacred music festival on the horizon is the World Festival of Sacred Music, put together by his Holiness, the Dalai Lama of Tibet. This ambitious event will be held in five cities on five continents, starting this fall in Los Angeles and ending next spring in Bangalore, India.

While the interest in sacred world music is understandable given the millennial context, confluence of technology, and people's desire to seek alternate truths, it's truly remarkable that world music has flourished the way it has despite little or no radio support. Perhaps this is also why it's not surprising that a town like Austin had its own vibrant international music scene.

Austin World Beat

If the term "world music" was coined in an English pub, then its precursor, "world beat," got its big push right here in Austin. One of the earliest and most vocal advocates of the term was guitarist, bandleader, and local disc jockey Dan Del Santo. Starting in the Seventies, Del Santo helmed KUT's world music show. His own music, published under the name World Beat Music, incorporated sounds, rhythms, and attitudes from many different longitudes and latitudes.

The title track from his 1983 release, World Beat, featuring local musical stalwarts Mike Mordecai on trombone, Tomas Ramirez on sax, and Eric Johnson on guitar, owes as much to Nigeria's Fela Kuti as anything going on in Austin at the time. When Del Santo left town suddenly because of drug-related legal problems, his radio show was taken over (and still run today) by the well-versed Hays McCauley, also the world music manager at Waterloo Records.

While there is no way to accurately measure how receptive a city is to world music, there's no question that Austin has a disproportionate interest in the genre. In addition to healthily stocked world music bins at local record outlets, there are a handful of regular radio programs featuring sounds from other continents. On KOOP's schedule alone are Music of the Middle East, African Ambiance, and Global Groovin'. KUT, KAZI, and KVRX also regularly play world music.

In addition to the Latin and reggae scenes in Austin, there are also a number of local bands, such as Tamasha Africana, the Gypsies, Kamran Hooshmand & 1001 Nights Orchestra, Tosca, and Rubinchik's Orkestyr, who travel musically. One individual who knows the local scene well is Jacqueline-of-all-trades Zein Al-Jundi. In addition to being a promoter for local acts and international groups (thank her for Angelique Kidjo's recent roof-raising show at La Zona Rosa), she also spins discs on KOOP's Dancing Around the World show. Having lived in Austin since the early Eighties, the Syrian-born Al-Jundi has the perspective to talk about Austin's world music of the last 15 years.

"There was a great deal of interest in this music in the Eighties," says Al-Jundi. "Dan Del Santo's shows, Susanna Sharpe, and a lot of world music shows came through Austin."

She describes the current scene more as a renaissance. "It's not necessarily a brand-new thing, but a rebirth of interest."

A quick list of recent touring shows in town certainly supports that: Chucho Valdés, Ricardo Lemvo, Kodo Drummers of Japan, etc. And like this week's Caetano Veloso show, UT's Performing Arts series is a big reason why Austinites enjoy the cream of the world's musical crop. In addition, there are other dedicated cultural arts organizations such as the Indian Classical Music Circle of Austin, which broadens the city's musical map. So which came first? The interest in the music, or the availability of it?

"Is it the chicken or the egg?" Al-Jundi asks rhetorically. "You put more music on the market, and there's more for people to buy. And the more people buy, the more record labels see financial rewards in releasing the music. It starts with someone liking the music enough to take a chance. If it works out, it then becomes a trend, and it's infectious."

The recent interest in world music has certainly benefited Russ Smith, founder and man behind Chocolate Records, a successful local indie that releases world music. When asked why world music has taken off, he responds with an oft-heard theory.

"After the Eighties," posits Smith, "people were just tired of hearing old stuff rehashed. With Peter Gabriel and Real World, and with reggae being so prominent, it opened up the Western ear enough to be hungry for other music.

"Our society is so void of spirituality that we're subconsciously hungry for things that lead us back to some level of sacredness. And things unspoken, like music and various forms of art, help."

World music may be, like electronica, merely a convenient tag for many different styles of music that have some loose association. And in fact, these two broad genres may be blending as groups like Cornershop and the Asian Dub Foundation are both techno-philic and incorporate in their music their multi-ethnic identities. Once more, it's not uncommon to hear DJs spin beats over Gregorian or Pakistani chants.

What does the future hold for so-called world music? Will it be discarded and useless after AD 2001, to be replaced by another episode of futuristic or cultural fascination? Like the one Bob Marley tune that our Moroccan chauffeur made a point to crank up on the drive to Fez, "Time Will Tell."

|

|