Record Reviews

Duke Ellington

Fri., April 30, 1999

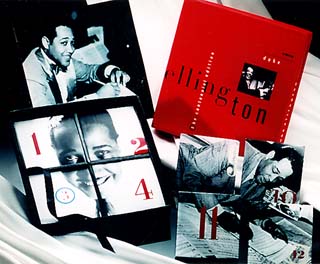

RCA Victor has come up with quite a project for the 100th birthday of Duke Ellington, the greatest jazz composer/arranger this country has yet produced and arguably the greatest composer in any genre -- ever. Ellington recorded for a number of labels during his long and prosperous career, but Victor owns the most and best material. Ellington recorded for them in every decade from the Twenties through the Seventies. The output for his 1940-1942 band, the best jazz big band ever, is on Victor, and you can follow his entire career from practically beginning to end on The Complete RCA Recordings (1927-1973), a mammoth 24-CD collection. It's expensive, retailing in the $400 range, but it's also an extremely important set, containing some of the most marvelous music of the century.

RCA Victor has come up with quite a project for the 100th birthday of Duke Ellington, the greatest jazz composer/arranger this country has yet produced and arguably the greatest composer in any genre -- ever. Ellington recorded for a number of labels during his long and prosperous career, but Victor owns the most and best material. Ellington recorded for them in every decade from the Twenties through the Seventies. The output for his 1940-1942 band, the best jazz big band ever, is on Victor, and you can follow his entire career from practically beginning to end on The Complete RCA Recordings (1927-1973), a mammoth 24-CD collection. It's expensive, retailing in the $400 range, but it's also an extremely important set, containing some of the most marvelous music of the century.

The material is divided into several sections, the first one being "The Early Recordings" (1927-34), which covers the set's first seven CDs. Ellington started out in 1927 with a 10-piece band that had expanded to 15 by 1940. His group grew in more than size, however. Ellington hired distinctive musical personalities, some staying with his orchestra, the most stable of big bands, for decades. Each individual influenced his concepts to the extent that Ellington created permanent spots for them, such as the growl trumpet role, created by Bubber Miley, but later filled by Cootie Williams and Ray Nance; the growl trombone of Charlie Irvis, then "Tricky Sam" Nanton and Quentin Jackson; and the breathy-toned tenor saw style of Ben Webster, Al Sears, and later Paul Gonsalves, the sweet-voiced alto saxman, Otto Hardwick, Johnny Hodges, and Willie Smith.

Ellington was not only a great composer/

arranger, but a superb leader who could spot talented, unique instrumentalists and showcase them beautifully. Ellington, a Washington, D.C., native, settled in New York in 1923, his original six-piece band, containing Miley, Hardwick, and drummer Sonny Greer, still with him in 1927. Already this was a distinctive outfit and Ellington an outstanding writer, as his "Creole Love Call," which featured Adelaide Hall's wordless singing, "Black and Tan Fantasy," and "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo" indicate. He had a broad musical outlook, drawing on Chopin as well as New Orleans-style jazz. Because of his use of growling brass, the orchestra became known as "The Jungle Band," but it was really a very sophisticated group which produced a wide variety of colors and textures.

It's not surprising, then, that even rhythm section members Greer, with his large drum kit including chimes, and bassist Wellman Braud, who perfected a slapping technique, contributed to the unique sound. In 1928, Ellington added a couple of important lyrical (or "sweet") voices, alto sax player Johnny Hodges and the unique and underappreciated trumpeter Arthur Whetsol, who'd played with Duke five years earlier. Hodges' mentor had been New Orleans clarinet and soprano sax great Sidney Bechet. Also coming on board was New Orleans clarinet star Barney Bigard, a master of register contrast, whose solos might begin in the basement then soar into the stratosphere.

Toward the end of 1928 and into 1929, the changes continued. Another trumpeter, the relatively flashy Freddie Jenkins, was added, as was Puerto Rico valve trombonist Juan Tizol. Tizol wrote "Caravan" and "Perdido" for/with Ellington, and probably influenced him to experiment with Latin rhythms. Harry Carney began concentrating increasingly on baritone sax, developing a huge tone and becoming the rock of the reed section -- if not the band. Early in 1929, Miley left, replaced by Cootie Williams, a great all-around player who eventually became known for his muted plunger work as well as a gorgeous open horn tone and enormous power. A plethora of gems was produced by this band, some sweet, some hot, including "The Dicty Glide," "Stevedore Stomp," "Misty Morning," "Cotton Club Stomp," and "The Mystery Song." An important breakthrough came in 1931, when Ellington cut "Creole Rhapsody," an unprecedentedly long performance that took up both sides of a 78rpm disc. It was the first of the bandleader's extended form pieces, a form he pioneered.

In 1932, trombonist Lawrence Brown, a brilliant technician with a big, lush tone, joined the band, followed by trumpeter Rex Stewart in 1934. From 1934-40, Ellington left Victor and cut masterpiece after masterpiece for various labels. On the lyrical, introspective "Reminiscing in Tempo" (eulogizing his mother), he continued to experiment with extended-form pieces; it was over 13 minutes in length. The ballads his band played, some written or co-written by his sidemen -- "In a Sentimental Mood," "Prelude to a Kiss," "Solitude," "Sophisticated Lady," and "Mood Indigo" -- became part and parcel of the Great American Songbook, along with tunes by Gershwin, Berlin, Porter, and Kern, and his repertoire was soon loaded with driving medium- and up-tempo tunes that featured dazzling improvised solos. Ellington didn't write for trumpet or saxophone; he wrote for specific musicians, turning out concertos for Bigard, Williams, Brown, and Stewart. Note too his unique ability to voice across sections, rather than pitting one section against another.

Ellington left Victor in 1934, returning to the label six years later in 1940 with tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, an exceptional player, and Jimmy Blanton, arguably the greatest jazz bassist. Around this time, Ellington added composer/arranger/

pianist Billy Strayhorn to his organization, a supremely gifted musical talent who wrote many memorable tunes for Ellington, including "Chelsea Bridge," "Johnny Come Lately," "Raincheck," and even the band's theme, "Take the A Train." In the case of the Ellington band, two heads -- his and Strayhorn's -- were even better than one. Taken together, these three men were catalysts for the Ellington Orchestra becoming the big band for the ages. At its peak, this unit produced a staggering number and variety of magnificent recordings: gorgeous impressionistic works like "Chelsea Bridge," the savage "Koko," the overpowering "Mainstem," the Latin-influenced "Conga Brava," the forward-looking "Cottontail," a piece based on the chord progression of "I Got Rhythm" that anticipated bebop. There are six CDs by the 1940-42 band here.

The sound of Ellington's reed section in 1940-42 was unlike that of any other band's, partly because of its makeup. Between the top, a clarinet and two altos, and the bottom, a baritone, there was only one tenor sax; consequently, the reeds sound grainier -- the distinctive voices of individual members come through more clearly. For his part, Blanton's big tone and technical proficiency astounded listeners. He played horn-like solos; his work was the foundation of modern bass playing. This set contains some terrific performances by small groups made up of Ellington sidemen, including the Ellington-Blanton duos. Tragically, Blanton was afflicted with tuberculosis and died in 1942 at the age of 21.

From 1942-44, Ellington made no commercial recordings due to an industry ban on recording imposed by the American Federation of Musicians, but he remained with Victor, cutting three CDs worth of material for them from 1944-46. This band included many members of the 1940-42 aggregation, but there were some key personnel changes: Al Sears replaced Webster, clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton came in for Barney Bigard, and Taft Johnson and high note specialist Cat Anderson joined the trumpet section, while Rex Stewart left. They continued to produce high-quality work, nonetheless, the most important being Black, Brown, & Beige, originally performed at Carnegie Hall in 1943. This suite, available on the Prestige label, is a 44-minute live performance subtitled A Tone Parallel to the History of the Negro in America. Though somewhat uneven, it contains some striking and lovely portions, and Ellington's most well-known extended piece. When he returned to the studio after the recording ban, among the first things he cut were excerpts from this piece. In general, there's less latitude for soloists on the three CDs that make up Black, Brown, & Beige than in a typical jazz performance -- some of the parts having been worked out in advance -- but there's plenty of richness in the spots of Carney, Sears, Hodges, Nanton, and Ray Nance (on violin) even if they aren't entirely ad-libbed. The piece is loaded with lovely melodies, colors, and textures.

Disc 17 contains a great 1952 Seattle concert by the Ellington Orchestra. By that time, he had trumpeters Clark Terry and Willie Cook, trombonists Britt Woodman and Quentin Jackson, Willie Smith for Johnny Hodges on alto sax (Hodges left Duke from 1951-55 to lead a small band), Paul Gonsalves on tenor, and Louis Bellson playing drums. This was a band that contained some bop-influenced soloists, including bassist Wendell Marshall, who was Blanton's cousin. Terry's long solo on "Perdido" is perhaps the concert's highlight. His improvising is incredibly loose and relaxed, his pyrotechnical effects amazing, his tone uniquely warm and soft. On "Jam With Sam," Ellington announces soloists to add to the dramatic effect and they respond with inspired work. Willie Smith, a star altoist with Jimmy Lunceford before joining Ellington, evokes the departed Hodges on "Sophisticated Lady" without sacrificing his own individuality.

The next three CDs contain Ellington's Sacred Concerts, cut in 1965, 1968, and 1973. These three Sacred Concerts were inspired by genuine religious feeling and idealism, and by most composers' standards, they have plenty of substance. Unfortunately, they're also corny and naive in places, especially the text. Solo and chorus vocal work are featured, and these do not compare favorably with the instrumental work of Ellington bands.

Finally, there are four CDs which have Ellington's 1965-73 albums: The Far East Suite; And His Mother Called Him Bill, featuring the compositions of Ellington's "alter ego," Billy Strayhorn; The Popular Duke Ellington; Duke Ellington at Tanglewood, spotlighting Ellington's piano work with the Boston Pops Orchestra and excerpts from The Jazz Piano, where he plays with bass and drums; and a 1973 live album, Eastbourne Performance." Plenty of alternate takes and previously unissued material are included, which will appeal to the scholar and are a pleasure to listen to.

The Far East Suite was inspired by Ellington tours to the Near and Middle East, India, and Japan in 1963 and '64. Most of the compositions were written by Ellington and Strayhorn together and are "tone parallels" to impressions and memories they had of those regions. The compositions are fresh and stimulating, the solos top-notch. Ellington and Strayhorn haven't tried to copy Asian music, but the influences are certainly there on a subliminal level.

The Popular Ellington is another album that's fine by most standards, but not Ellington's. It contains familiar material and is frankly described by producer Brad McCuen as primarily designed to be an accessible record that sold.

It's nice to hear Ellington's piano work highlighted in a small combo in Jazz Piano and with a large ensemble in Tanglewood. Duke was a very original soloist, initially a member of the stride school, which included James P. Johnson, Willie "the Lion" Smith, and Fats Waller, but his style evolved into something completely unique. A percussive player with an orchestral approach on some occasions, Ellington also played lightly and sparsely à la Count Basie. He was also a precursor and perhaps an influence on Thelonious Monk. Richard Hayman's arrangements on the Tanglewood tracks are corny, but hey, what can you expect when Arthur Fiedler's involved?

And His Mother Called Him Bill, recorded after Strayhorn died of cancer in 1967 (Ellington was distraught), pulls together a group of wonderful pieces that aren't well known to the general public, such as "Upper Manhattan Medical Group," "Raincheck," and Hodges' ultimate tribute to Strayhorn, "Blood Count," written by the diminutive songwriter while on his deathbed in the hospital. The album is a delightful effort.

By the time of Eastbourne Performance in 1973, the year before Ellington died, most of the stars of the bandleader's previous bands had gone, though Carney and Russell Procope, a fine clarinetist/alto saxman, who came to the fore in the Thirties, remained. Still, this is a fine album, with trumpeters Money Johnson and Johnny Coles and tenorman Harold Ashby making significant contributions. For me, though, Duke is the star soloist, playing jauntily on "The Piano Player" and pensively on "Mercuria, the Lion." At 74, his work remained unpredictable. He still had it goin' on. Still does. -- Harvey Pekar