The Primary Source

By Christopher Hess, Fri., Feb. 26, 1999

|

|

History is subjective. It's the perception of events that can't be experienced firsthand -- a reconstruction composed partly of memory and partly of imagination. Webster's New World Dictionary defines history as "an account of what has or might have happened, esp. in the form of a narrative, play, story, or tale." Note the use of the word "might." To separate history from myth, the person in the present must take the messenger from the past at his or her word.

If your understanding of this country's political history comes from textbooks, as it does for most of us, then you trust that the people who wrote said account are proliferating an accurate representation of the events. If your history is informed by stories passed down from parents and grandparents, then you take it for granted that they're telling you how it was and not how they want you to think it was. Newspaper articles, tax records, diaries, and notches carved into a doorjamb all tell of the growth of an individual, family, or country.

|

|

"Historical record as it's presented through journalism and through scholarship reflects the social reality of the society you're living in," says Harold McMillan, head of DiverseArts productions and the Blues Family Tree Project. "If you live in a segregated, racist society, chances are scholarship on marginal communities is not gonna be at the forefront of importance of those who are signing off on dissertations. So there's this huge historical hole there."

In assembling a cultural history of black East Austin, the mission of the Blues Family Tree, McMillan has gone straight to the source. His archives are overflowing with photographs, audio recordings, videotaped performances, and interviews he has made and compiled of many important figures in the blues scene across the tracks, which saw its heyday in the post-World War II era. The passing of time and people who were around back then, paired with the lack of any sort of secondary sources (newspaper accounts, academic examinations, documentaries) presents a significant barrier to gathering this information. When McMillan talks with the musicians who were there -- James Clay, Ural Dewitty, Grey Ghost, Erbie Bowser, T.D. Bell -- Austin's Eastside, known today only through third- and fourth-hand accounts, comes to life.

The idea for the Blues Family Tree came to McMillan as a graduate student in American Studies at the University of Texas in the late Eighties, although more by necessity than inspiration. Originally, he envisioned himself traveling to Paris, France in order to document the roots of the black jazz scene in that city after World War I. The idea of living and studying in Paris was admittedly a big part of the plan's genesis, but there was more to it than that. Research for a seminar on Modernism revealed a shocking and enlightening realization: Although there already existed mounds of historical research and scholarship on the Modernist art of the time period, McMillan could find scarcely any mention of black artists. The cultural phenomenon of the Twenties that came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance -- the paintings of Archibald Motley Jr., the writing of Langston Hughes, the music of Duke Ellington, to name but a few examples -- was all but ignored in relation to the work by artists of European descent.

|

|

Dreams of Paris were predictably squashed by institutional frugalities, but by this time, McMillan was discovering that there was a historically ignored cultural scene right beneath his feet that merited documentation. "At the time," recalls McMillan, "I was playing blues in public. I was at Antone's a lot, probably with Major Burkes or Matthew Robinson."

A history of the blues in Austin as seen from the stage at Antone's was an enticing option for a graduate school project, and access to the living legends of the blues, which Clifford Antone was bringing through his club, was an exciting prospect indeed. Naturally, it didn't take McMillan long to discover that the same thing he found in studying European-inspired art forms around the turn of the century was true of blues music in modern-day Austin, Texas. Everyone knew about Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan and the Antone's scene -- and likewise about Willie Nelson and Jerry Jeff Walker -- but what about the Cadillacs or the Jets? Who was writing about Reggie Caldwell or Snuff Johnson? There was an entire culture that was being marginalized, if not completely ignored, by the east-west boundary of Interstate 35.

"James Polk told me that about even the liberal university areas," says McMillan. "He had gigs on the Drag where friends who were black couldn't come and hear him play. And James Polk is not 100 years old. The thing I think that we, the hip-and-cool Austin generation, don't realize is when we're talking about this history, we're not talking about 100 years ago or even 50 years ago. We're talking about 20, 30 years ago -- within our lifetime. That's more significant than a lot of people want to let on. We're not talking about South Africa here, it's the U.S. of A."

Langston Hughes, the African-American writer at the fore of the Harlem Renaissance in literature, once wrote, in defending himself to readers who complained that his characters were not very flattering portraits of his subject, "I knew only the people I had grown up with, and they weren't people whose shoes were always shined, who had been to Harvard, or who had heard of Bach."

|

|

In much the same sense, the Blues Family Tree is not concerned with an exact account of economic trends or political events -- although those things do come into play. During an interview, someone like the late guitarist T.D. Bell might offer his thoughts about Austin's mayor at the time, or Johnny Holmes, the proprietor of the Victory Grill, might recall how much it cost to get into his club to see Clarence Pearce and the East Side Band, but these specific pieces of information are less important than connecting a cross section of remembrances that create a more complete impression of the time.

McMillan insists that he's not a historian, that he's not even a blues expert. Yet he knows he's doing something of utmost importance to the understanding and preservation of a seminal cultural force in our city. Considering that Austin's blues scene has been widely acknowledged as one of the most influential in the state of Texas, the country, and perhaps even the world, this is no small undertaking. In preserving the experiences of musicians who lived and played in East Austin, McMillan has begun defining a wide net of connections between people and places, and through their accounts, is piecing together an overall sense of what life was like at the time. As it turns out, what life was like was a whole lot different than it is today.

A trip up and down 11th and 12th streets just east of I-35 leaves passersby hard-pressed to believe there was once a thriving entertainment district there, let alone a bustling and fully functional community. A couple of clubs remain today, only one of which, the East Side Lounge, is open full time. There's also Ben's Long Branch barbecue, still some of the best brisket to be found in Austin. Mostly, though, there are a lot of empty buildings and bare lots. The change happened quickly, as it turns out, spurred, ironically enough, by the desegregation of the mid-Sixties.

"Once you go back to pre-integration black East Austin," explains McMillan, "what you've got is a community that had cultural institutions, and commerce, and people with money, and people without money, and crime and people with jobs and people without jobs, but it was a normal, functioning community. One of the things that segregation did for black folks was provide some amount of insulation so that they knew what was going on in the community, and their institutions were granted respect.

"There was a point where black East Austin had two colleges, for instance. Two colleges, lots of churches, barber shops, theatres, hotels, doctors, grocery stores -- stuff that's hard to believe today, but that used to be the situation. Part of it was that's the only place they could do business in Austin, but that had its advantages culturally."

|

|

"Old Anderson High School in black East Austin was a major educational, cultural, social institution," says McMillan. "Major. It had history, tied to a local family, athletes, debates -- smart guys who went on to do great things. All the musicians I talked to who took music in school went to Anderson, and they talk about Mr. Joyce, who was everyone's band instructor. But when you desegregate and begin busing, you don't bus white kids from Westlake to Anderson in 1968, you close Anderson. Integration did not happen with desegregation. It's a whole different thing."

Though it didn't close its doors, Huston-Tillotson College suffered from the same migrations. Once an East Austin institution that was a primary destination for promising musicians from around the country -- drawn by a nationally renowned music program and names like Nat Williams and Bert Adams who offered education, cultural enrichment, and opportunity -- the school now lies entirely in the shadow of larger schools like UT and Southwest Texas State in San Marcos.

While it may seem odd that the most socially relevant historical study of this city is being done with no consistent funding by an avowed local non-historian and a revolving cast of interns, in a way, it's appropriate as well. Government records could tell you all about LBJ's political activities in the name of social welfare, as well as a good deal about the statistical effects the policies had on the larger Austin community, but what's missing is an account of the people, and to a large extent, what kept the people together -- music. The blues, in its original form, was a predominantly vocal expression, and in a thriving musical community without access to or need for recorded product, the handing down of songs and stories (and thus history) remains an oral exercise.

Here in 1999, with the East Austin blues scene all but gone -- the foundation of Austin's most vital and historically significant musical community -- the Blues Family Tree could end up providing the only link between past and present, in establishing a continuum between Grey Ghost and the future stars of Antone's.

"The foundation to build this work on is very shaky," asserts McMillan. "There's not a documentary record that's easily accessible -- that's out there already. So, [the project's] first importance is probably remedial, to establish something where there wasn't anything in the past. For the future, I'm a real believer in cultural history telling you a whole lot about a group of people, a community. I think it's important to provide a venue for people who are experts on their situation -- who are also not scholars, academicians or journalists -- to have some way of getting their story into the historical record.

"Unless you talk directly to those people, you only get some mediated, filtered version of it. Besides that, it happens to be stuff I'm into. I like to look through old magazines, listen to recordings done many many years ago. I like to hear people talk that are dead. And I'm not the only one. The Austin History Center is built on that. There are archives all over the world that are built on that. It's one of the ways to preserve your history and learn about your culture."

|

|

Thus far, the visible results of the project are manifest mostly in the annual Blues Family Tree performances, which this year take the form of tonight's (Thursday) Lavelle White Songbook show at the Mercury, as well as small exhibitions of black-and-white photography, the occasional screenings of a 30-minute documentary that McMillan, with the help of the U.T. film department's Sandra Carter, completed as a graduate school requirement, and live performance footage broadcast regularly on the Austin Music Network.

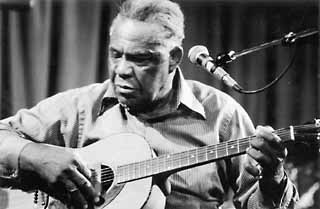

As the years wear on, and people like A.C. Littlefield, co-founder of gospel pioneer group Bells of Joy, Huston-Tillotson's Bert Adams, and blues guitar hero T.D. Bell, to name only a few very recent examples, disappear into memory, the work being done by McMillan and company takes on a more immediate importance. Last year's Blues Family Tree show, a performance by T.D. Bell & the Blues Specialists at Antone's, is a perfect example. Bell was a hugely talented and greatly respected guitarist in this city starting in 1951, but his recorded output is limited to a few hard-to-find early recordings and the It's About Time CD on Catfish Records.

This show, however, even though the day saw a torrential downpour that kept attendance to a minimum, was possibly as near a perfect performance as Bell ever did, and it's all on video and digital audio tape. The video, directed by Michael Emery, also a significant contributor to the Blues Family Tree archival project, should be seen by anyone interested in T.D. Bell. And if the recording were released as a CD, it would be an essential presence in the collection of any serious fan of Austin blues -- or of blues in general.

People die. Neighborhoods change. Cultural landmarks and community identities shift and adapt to the social and political realities of the time. But when these changes happen so fast and continue without any recognizable sign of a return to form, as has happened with the 11th-12th street corridor on Austin's Eastside, in the absence of a historical record -- whether it be that of an "official" historian or not -- the culture of the time is threatened with extinction. Plant a family tree, however, connecting roots to trunk and branches while providing room for the extension of all of them, and there exists not only a reminder of what's come before, but also a solid foundation for what comes next.

The DiverseArts Productions office space and gallery, in the ArtPlex building at 1705 Guadalupe Ste. 234, currently has a selection of Blues Family Tree photographs on display. Call 477-9438 for information about the exhibit, the concert, or the archives.