Roots, Reckonings, and Resolutions

Roots

By Jay Hardwig, Fri., Nov. 27, 1998

|

|

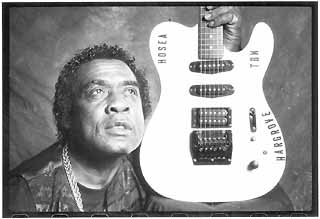

"It's a long story, me and my guitar playing," says Hargrove. "I just came up playing." The place he came up in, Crafts Prairie, didn't hold more than about 50 families, but it was a hotbed of blues players in the Thirties and Forties, producing not only Chase, Williams, and Grey Ghost, but also Hosea Henderson, Sugar Taylor, "Funny Papa" Smith, and "Sunny Boy" Williams, all prominent players in their own right.

When their work in the fields was done, the folks of Crafts Prairie would gather for music, playing on front porches in the fading light, sometimes joining one another for a supper show. Hargrove watched, picked up what he could, and went home to practice. Formally untrained, most of his lessons came from his father and from Son Chase, who welcomed the younger Hargrove into his house and showed him a thing or two about down-home blues. It was Chase who gave Hargrove his first guitar, "a little ol' Stellar," recalls Hargrove, and Chase who took Hargrove to his first show, doubled up on the back of Sonny's horse.

Unadulterated country blues, banged out on acoustic guitars, was the name of the game, and by the time Hargrove was a teenager he was playing in small towns around Central Texas -- Smithville, Taylor, Elgin, Lockhart -- and making something of a name for himself. After graduating from high school in neighboring Smithville, he stayed in Crafts Prairie to help his uncle with his farm. It didn't take long to realize that there wasn't much future in small-time farming, however, and in short order Hargrove lit out for Dallas to try and find a paying job, his Stellar tucked tightly in tow.

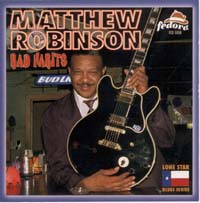

For Matthew Robinson, growing up in the St. John's neighborhood in northeast Austin, things weren't a whole lot more citified than Hargrove's Crafts Prairie; I-35 was just a two-lane dirt road, and out beyond his neighborhood was a brambly thicket just right for "rabbit-running," camping out, and general horseplay. The St. John's neighborhood was all black at the time, and Robinson remembers it as a close-knit community.

"Everybody knew everybody in the neighborhood," says Robinson. "If I was over at a neighbor's house playing and messed up, they would call to the house and say, y'know, 'Matthew's over here messing up and I gave him a whuppin' and he's on his way home.' I'd get about two or three whuppins on the way home, too. Folks saying, 'I heard what you did over there.' These days you could stay next door to someone a long time and not know who they are. I mean, right next door."

The center of the community was the St. James Baptist Church, and one of Robinson's most distinct memories of childhood was his baptism in the Colorado River. Dressed in white robes and singing a cappella, the congregation marched down from the church to the riverside. Standing in line, Robinson recalls it didn't look that bad. A little spot under the water, up and down pretty quick. But the preacher held Robinson down just a little bit longer.

"I must have really needed it bad," Robinson figures, "because I came up [gasping for breath]. It was something. I don't think you could do that now. It's probably against the law, first of all, and its probably polluted now. You don't want to get in there."

By the time he hit third grade, Robinson's family had moved "in town," to Rosewood and Chicon, where the action was livelier and music was all around. The family moved around the Rosewood and Springdale neighborhoods, "from old projects to new projects," for the rest of his youth. Throughout, there was music and religion. Robinson's father, Matthew Sr., was the youngest of seven brothers, and the only one who didn't answer the call to preach. Instead, he got the gift of music.

"He was the kind of person you could give an instrument to, and he would come back a couple of days later, and just be playing it. He might be holding it wrong, but he'd be playing it."

Matthew Sr. played piano and sang with the choir, but saved his best for backyard guitar.

"One reason I stayed away from guitar for so long," says Matthew Jr., "is because I thought you had to be a magic person to do it. He could just tear that thing up."

Matthew's mother, Vivian, was also musical, singing in gospel choirs around town and always carrying a tune in her head. The children learned to judge her mood by the tune she was humming, and knew when to stay clear. And the blues were strictly forbidden -- the devil's music.

"That's why it took me so long to get into it," explains Robinson. "When I finally did, it was amazing."

Reckoning

It was in 1949, at age 20, that Hosea Hargrove left Crafts Prairie for Dallas to look for work. Found some, too -- washing dishes in a local restaurant -- but he held onto the dream of playing guitar. Every night after work, he'd go home and practice, or listen to the old-time blues on the jukebox at the neighborhood saloon: Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lightnin' Hopkins, B.B. King. Hopkins was a particular favorite, says Hargrove, "'cause he played it low." There were times, too, that he'd pick up some country & western on the radio, and though he never played the style, to this day Hargrove considers himself a Bob Wills fan.

It was in 1949, at age 20, that Hosea Hargrove left Crafts Prairie for Dallas to look for work. Found some, too -- washing dishes in a local restaurant -- but he held onto the dream of playing guitar. Every night after work, he'd go home and practice, or listen to the old-time blues on the jukebox at the neighborhood saloon: Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lightnin' Hopkins, B.B. King. Hopkins was a particular favorite, says Hargrove, "'cause he played it low." There were times, too, that he'd pick up some country & western on the radio, and though he never played the style, to this day Hargrove considers himself a Bob Wills fan.

After Dallas came West Texas, pulling cotton by day, playing guitar by night. Hargrove was one of the last of the traveling musician-pickers, once a dependable feature on the West Texas landscape. It was the early Fifties, and Hargrove played to eager fieldhands all over Texas and New Mexico. Yet it was in Phoenix, Arizona, that he played his first electric guitar, taught to him by a man named Willie Thornton.

"He had a little ol' electric guitar and he'd set it over there and play it," Hargrove recalls. "And he could play his guitar just like the records, you know. I was listenin' to that, sayin', 'Man, I'd sure like for you to learn me that, man.'"

Hargrove stuck around long enough to learn to play like his man Lightnin' and before long he was gigging around Phoenix with Thornton, playing amplified takes on the country blues he had grown up with. It was those electrified country blues -- known as "transitional blues" in some camps -- that Hargrove brought back to Central Texas in 1956, settling on Austin's Eastside, where the nightlife was jumping, T.D. Bell was the local star, and Matthew Robinson and his shinebox stood waiting on the corner.

Hargrove's music reflected his journey, from acoustic country roots to the electric city life, but it never took on the urban polish of a B.B. King or T-Bone Walker, who brought swingin' horns and a chart-reading sophistication to their own country blues. Instead, Hargrove stuck with the standard three-piece of Texas' early electric blues -- two guitars and drums, or alternately, guitar, bass, and drums -- playing Eastside clubs like the IL and the Victory Grill and establishing himself on the small-town Texas circuit.

In the 40 years since, he's been a fixture on the Austin blues scene, laying down his transitional sound and taking time to school a few of the younger players who have come searching for the real thing. Like Jimmie Vaughan, for instance, who looked up Hargrove when he first came to town (pre-Storm, pre-Thunderbirds), learning at Hargrove's side. The two teamed up and started playing together, traveling the circuit and surprising a few of Hargrove's regular fans.

"They were surprised to see a white boy playing the blues like that," Hargrove says, admitting that Vaughan could play some mean guitar long before the two ever met. "He was young, but he could play those blues, you know."

In interviews, both Jimmie and his brother Stevie Ray acknowledged Hargrove's influence on their style. In fact, when Jimmie Vaughan first got the Fabulous Thunderbirds together, he asked Hargrove to join as a vocalist, but Hargrove declined.

"I said, 'Man, I don't want to sing, I want to play guit-tar.' I probably coulda went all the way with them."

Jimmie Vaughan also figures prominently in Matthew Robinson's reckoning, although by that time the tables were turned, with Vaughan giving advice to a struggling Robinson. Vaughan is just one of a number of key figures that Robinson conjures when relating the story of his own musical odyssey.

The first is Calvin Thompson, original guitarist for Austin's legendary gospel group, the Bells of Joy. Robinson was surrounded by music in his youth, but it was watching Thompson that inspired him to make it his life's work.

"It was so magical the way he did it," he says. "He didn't miss leads or anything, and it was such a joyous thing. I [knew then] that's what I would like to do."

Robinson started singing at local sockhops, and in 1964 formed his first band, the Mustangs. With the aspiring guitarist singing lead, the Mustangs achieved some prominence in the Sixties, touring nationally and opening up for a number of legends, James Brown, Jimmy Reed, and Big Mama Thornton among them. It wasn't until the band's demise that Robinson decided to pick up the guitar. It was slow going at first -- bad tone, sore fingers -- and a frustrated Robinson almost called it quits. It was then that Vaughan stepped in with some simple words of encouragement: "Don't worry about it, you'll get it."

His next savior was local bluesman W.C. Clark. Clark had been watching Robinson practice, playing complicated lines and chords he would never use.

"At the time, I had bought a book titled 1001 Chords," says Robinson, his voice rising with amusement. "It had all these chords, which I learned. Every one of them. But to this day, I probably haven't played no more than three or four of those chords."

It was Clark who suggested a simpler course of study -- 26 chords, tops -- that Robinson still uses onstage.

Finally, Robinson credits Count Basie, whom he met at the Armadillo shortly before Basie passed away. The Count told Robinson that learning to play music was a lifetime project, that a day didn't pass when he didn't pick up something new.

"To do this," Robinson realized, "you're gonna have to work at it. It's not just gonna fall. Like Basie, just jumps in there and whups it, no problem. But I imagine he had to work at it too."

If Robinson's guitar chops came along slowly, it didn't help that he had been playing for two years before he learned how to tune his instrument.

"I didn't even know you were supposed to tune it when I first started," he laughs. "So, if I learned a song and the next day somebody had turned something or it went out of tune, I had to learn it again. It was strange. That's why my lines are weird like that when I play now, because I still hear that."

It may have taken years, but Robinson eventually got the hang of it -- tuning pegs, 26 chords, and all -- and in time developed his own style, a clenched, staccato delivery that complements the sly grit of his voice. His fretboard influences run from John Lee Hooker to Jimi Hendrix, Django Reinhardt to Andrés Segovia.

"Anybody who played, [I would listen] to hear their voice, and wonder how they felt to get like that."

Resolution

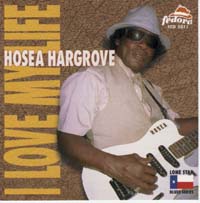

Forty-four years after he first went electric, Hosea Hargrove is still playing his hopped-up transitional blues. He still tours Central Texas, works a few Sixth Street gigs, and keeps a steady presence at the Eastside Lounge, the small neighborhood bar that has quietly done more to keep old-time Austin blues alive than all the downtown clubs combined. But while Hargrove still packs the Eastside Lounge, his name doesn't cause much of a stir west of the interstate.

Forty-four years after he first went electric, Hosea Hargrove is still playing his hopped-up transitional blues. He still tours Central Texas, works a few Sixth Street gigs, and keeps a steady presence at the Eastside Lounge, the small neighborhood bar that has quietly done more to keep old-time Austin blues alive than all the downtown clubs combined. But while Hargrove still packs the Eastside Lounge, his name doesn't cause much of a stir west of the interstate.

There are some who notice, however. Like Tary Owens, blues archivist, founder of local indie label Catfish Records, and self-described Hosea advocate. Owens considers Hargrove a living legend. "Hosea is an absolutely vital link between the country blues of Lightnin' Hopkins, Little Son Jackson, and Blind Lemon Jefferson to modern blues. ... He's a direct link to the origin of the blues in general, not just Texas blues."

Asked why Hargrove is a relative unknown outside of the black community, Owens points to the elemental nature of his guitar work. Folks these days are looking for flash, while Hosea plays a subtler style. "Hosea plays that wonderful simple blues that if you complicate it too much, add too much to it, you kind of mess it up."

"Simple" and "basic" -- two words that are used a lot in the context of Hargrove's guitar. And it's true: You won't find a lot of sophisticated fretwork at a Hargrove show. A lot of folks mistake that simplicity for a lack of talent, but Hargrove has the sound he wants, deep-in-the-bucket and unwed to the standardizing effects of the modern blues idiom. It's a sound that relies more on the depths of one's soul than the speed of one's fingers, akin to Lightnin', John Lee Hooker, and some of what you'll find on the Fat Possum label these days.

"Hosea is a true primitive in the best sense of the word primitive," says Owens, adding that Hargrove's unadulterated country blues is a style that has almost passed from the landscape. "The real thing -- before it got molded."

And here's another truth: If you've only heard Hosea Hargrove with his current get-up, the Enter City Band, you haven't heard Hosea Hargrove. It's no knock on the band, who are slick enough at the standard white-boy blues, but rather a comment on Hargrove's style. He doesn't need the help. For a truer taste of classic Hargrove, spin Fedora's I Love My Life. Here, you'll find Hargrove stripped to the bones, dealing in essentials, with only the most basic instrumental support. Listen to the two tracks with no backing at all, "Things I Used to Do" and "I'm a King Bee," and it becomes clear that Hargrove doesn't need a saxophone wailing at every break. All he needs is a guitar and an amplifier, and the amp itself is damn near optional.

Robinson's story is a little different. After more than 20 years in the sidelights, playing with such local heavies as James Polk, W.C. Clark, and Blues Boy Hubbard, he finally has a band of his own. He's been playing with the Texas Blues Band since his amicable split with Hubbard in 1996.

It's been all up since then: steady gigs, a growing audience, the Fedora release, and a slew of Austin Jazz Festival honors, including "Best Blues Group" and "Best R&B Singer" at the 1998 festival. And while he tours a little bit nationally, he's more taken with the international scene; he's played Brazil twice, Holland three times, and has trips already lined up for France, Spain, and Australia. He'd love to take more stateside shows, he says, but can't get the time off work -- seems the blues don't quite pay those bills. Robinson has worked full time as a custodian at the Texas School for the Blind & Visually Impaired for 15 years, and does custom floorwork on the side.

Sure, it wears him out, and he'd love to quit the school and play music full time, but he's not complaining. He's closer than he's ever been to a dream he's had since he first saw Clarence Thompson work his magic with the Bells of Joy.

"I had already made up my mind then, in the second grade, what I really wanted to do. So I'm doing it, but I've always had to [take other work] to get there. You know, some people are lucky or just have more talent, and got there faster, but I always said I don't care how long it takes, I'm just gonna go ahead and do it. It's a lot closer than I ever imagined. It's coming fast, too."

And if, at the age of 69, it's come a little slower to Hosea Hargrove, he seems content to sit and wait on it. Retired from the Austin State School, Hargrove's at ease with a relaxed pace, returned in kind to his rural roots. "I don't do nothing but raise garden, go fishin', and play a little music on the side. That's about it."

He says it so free and easy that you think he might be about ready to retire from the blues as well -- more time for fishin'. Not so, he says.

"I've been playin' blues stuff so long, I don't know how it would feel not playing. I ain't got it in mind to retire. I'm thinking about trying to get further if I can. As far as I can go."