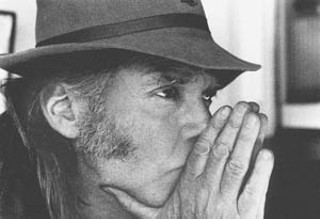

Old King: Neil Young and Jonathan Demme in Nashville

Harvesting Neil Young's new 'Prairie Wind'

By Louis Black, Fri., Aug. 26, 2005

This isn't really the return of "Page Two." Instead it's a ... well, not a review exactly, but rather a meditation on Neil Young's mid-August Nashville performances of his new album Prairie Wind. Director Jonathan Demme shot the shows for a film to be released this fall.

There was so much to these shows. They were rich in music, personality, and meaning, with brilliant new songs, revealing versions of the old ones, terrific and numerous musicians, all swirling around Neil Young at his most inspired. As with the best of Young's music and performances, there were any number of themes both to the new album and the shows. Even though I believe in trusting the art and not the artist, I come back to the autobiographical, not as a way to capture the shows or reduce their meaning, but because in that way they're immediately explosive and then continually unfolding.

When my memory is flickering at the doors of those shows what I see first is always the same and always wrong. I know it's wrong, but maybe it's a vision, if you will, maybe even a greater truth.

Neil Young is alone, a spotlight burning down on him, and there are no backup musicians. He's sitting on a chair with an acoustic guitar, wearing his wonderful Manuel's suit and broad-brimmed hat. Occasionally Pegi, his wife of two decades, joins him playing guitar and singing backup while sitting in the chair next to him. This isn't metaphor; every song has the same kickoff. That's really the way it enters my memory, like the smell of the ocean when you're still so many miles away.

I remember the show as just Neil or Neil and Pegi. That's wrong, but that's the memory. His face, a map detailing too many generations of emotions, follows the lead of his smile, his eyes twinkling. They're so deep you can't begin to find them and wouldn't dare follow them. He tells a long story about his bluetick hound Dean by way of introduction to one song. I realize there's something extraordinarily animal about Young. Not overly fluid or natural, but just in the way he's always looking out – in the way he moves, edgy and unsure, almost completely certain of himself but not of the territory. He's constantly ready (maybe to run, maybe to pounce), as he's constantly circling the stage, the music, and the audience.

Young's last work, 2003's Greendale, was typically assaulted by some of the critical mob. I saw it in Toronto expecting nothing. I was so delighted by the work I couldn't stop smiling. Critics are always trying to contain Young, to figure out how to categorize him using existing definitions. Greendale may be as much a play – a stage event – as it is an album, but why try to confine Young with words when he's so completely not confined creatively? The day after Young's performance, he was interviewed by Elvis Mitchell. There were so many insightful moments during the interview, but one thing I will always remember was Young's sheer happiness as he talked about how great it was to do Greendale because he got to perform "10 new songs in a row."

After Greendale, Young had sworn off recording new material (rumor had it that he was feeling written out), but instead was planning on concentrating on finally releasing his archives, a multi-album, multi-DVD project that would be scheduled over 18 months (at least).

Then, earlier this year, quite unexpectedly, Young was diagnosed with a brain aneurysm. He wrote all the songs for Prairie Wind – an entire new album – between the diagnosis and the operation. The operation was successful.

At the storied Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, he performed it in its entirety, then followed with a set of older material. This material was almost entirely from Harvest and Harvest Moon, quite appropriately as Prairie Wind very much concludes that trilogy. Featuring songs that stand up with his best material, Prairie Wind is not only a stunning work, but also one that reimagines all that proceeded it.

I saw the show three times – one run-through and two performances. Given that I have the attention span of a gnat, I'm usually not given to attendance at multiple shows, even of favorite artists, but on Friday night at the end of the second performance I was ready to come back again the next night. The Ryman, former home of the Grand Ole Opry, is one of the great music halls in this country, especially, though not only, in regard to ambience, intimacy, and acoustics. Several times Young commented that he felt like he was inside a guitar.

The show unfolded over the course of the evening, Young accompanied by 30 or more musicians on stage at one time or another. They came on, they exited, they returned in a different configuration, switching instruments and positions. Watching Young during the run-through performance is extraordinary, his sense of music broken down to every instrument without losing sight of the sweep of the work. He sees the forest for the trees, noting the smallest detail without losing any sight of the grandest ambition.

This is not going to be Neil Young's Stop Making Sense. Demme and Young were both working on a grander, less focused tableau where the excitement is visceral if not as immediate, the richer pleasures derived cerebrally from lyric, history, and juxtaposition. Still, it works so beautifully musically that it would hit the groove if there were nothing else to it.

But there is: watching Neil and Pegi Young smile at each other. This is a work about mortality and friendship, about romance and sadness, about everyday love and family, about history, the present and the future, the land and its people, Canada and the United States.

Emmylou Harris joined Young on a number of songs. Ben Keith played steel guitar throughout. Other players included guitarist Grant Boatright, drummer Chad Cromwell, keyboardist Spooner Oldham, bassist Rick Rosas, and fiddler Clinton Gregory. The Fisk University Jubilee Singers, the Nashville String Machine, and a horn trio led by Wayne Jackson of the Memphis Horns also joined the fun at different points. Usually they would join for whole songs, but the choir came out part way into a song to join in, and the string section made an appearance in the middle of a song to play on a section and then left.

The staging was ideal, only a few different backdrops, the lighting superb, and the clothing from Manuel's – suits that are hip and retro. The performance looked like an early photo process color postcard, a 1940s traveling country & western show as well as an almost too trendy modern cocktail bar.

Prairie Winds is an exquisite journey; I can't begin to talk about it as a concert. It was something so much bigger, finally reminding me of nothing so much as Brian Wilson's Smile, the entire concert of a piece. Rather than resurrecting a lost, never-finished album, this was a whole new creation. And not just Prairie Wind; the older songs were equally important in shaping a cohesive whole. Young wrote these songs for the times in which they were composed and the albums on which they appeared. Still, it was like Smile in the way it combined the known and the new, memory and dreams. Songs and even just pieces of songs and/or music from Smile ended up on at least a half dozen other Beach Boy albums. Listening, you knew them as distinct songs. The revelation was in how they fit together. The same was true of Young's performances, songs like "Old Man," "Needle and the Damage Done," and "Comes a Time" perfectly crafted for this mosaic, feeling born to their place rather than shoved in or just played randomly for an encore. The older songs finally seemed at home: All the music together formed a startlingly mature work that, while denying none of life's tragedies, insisted that the direction is forward.

Young has always pushed boundaries while continually reinventing himself, but given the darkness of so much of his material, the warmth and celebratory aspects of this work literally give the audience chills. Imagine "Needle and the Damage Done" not as a "Tonight's the Night"-type lament but instead as a hymn of affirmation: "I've seen the needle and the damage done. A little part of it in everyone. Every junkie's like a settin' sun."

The emphasis is on "a little part of it in everyone." The meaning of that line has certainly changed for this listener over the years and I bet for Young as well. Once I think he was talking about the damage everyone carries that has been done to him or her. Now I think it also includes the damage that each of us has done to others.

Young is among the most inconsistent of artists in terms of what material he actually packages and releases. Given the rumored amount of unreleased material in his legendary vaults, at best we're only seeing the phase of himself that he offers at any time. Every release by Young is a mystery until it's heard, often turning out to be very different than any advance word might have lead one to suspect. Young is so driven and so drives his art that he would rather fail ignominiously or magnificently than play it safe.

The careers of artists who keep pushing the envelope, who refuse to rest creatively, can take any number of arcs. One of the most common is where it's as though the creator has simply run out of ideas and passions so they substitute generic changes or revisit old material with either too much affection or way too much aggression. Given the current poverty of ambition and imagination in American popular culture criticism, odds are overwhelming that during a particularly extended experimental period the talent will be written off if not turned on and attacked for attempting the very kinds of ongoing experimental work other artists are criticized for not undertaking.

Another arc is the artist who keeps evolving, changing art forms and focus, and keeps succeeding, going out of critical favor only rarely – a focused, rising, well-received, and innovative career.

Problematic is the career of a talent determined to push past all previous boundaries. This is especially true if the artist is microfocused with brilliant, enabling, and accommodating management. In these circumstances sometimes the best way to determine too far is failure.

It's not doing what has worked. It's not even doing what one knows will work. Instead it's taking a couple of steps beyond what is safe by any stretch of the imagination. Usually, almost predictably, though derided for some work (hey, it makes for good writing), when they again hit a grand slam they are overly celebrated (hey, it makes for good writing). They're hailed as though they've returned from the dead. What's missing is a measured consideration of an ongoing career.

There are so many pleasures to Prairie Wind, those of the ear and those of the soul. Still, Young, always a genius of the gesture, here delivers a mighty fuck-you to any and all detractors – critics, industry, and fans alike – though one offered so politely, quietly, and nonchalantly that it might not even be noticed.

Harvest (1972) was Young's most successful album. Twenty years later, there was Harvest Moon (1992). Now 13 years later there's Prairie Wind. The songs are so exquisite they argue that any time over the last 33 years Young could have spent a couple of years churning out Harvest-type hits with no trouble. Making popular albums is hard, but nothing like following your talent where it leads you, finding personal satisfaction in the voyage while trusting that at some point this path will connect with a larger audience.

I'm not suggesting regression by Young or that he's finally selling his talent short in doing these songs linearly descended from Harvest. Just the opposite. Young was finally at a point – again – where what he wanted to say creatively was in line with Harvest. These songs, however, wear every day of the 33 years that have transpired since. Young's new work has always represented change and embraced challenge; his older songs, while always maintaining a core identity, have aged and changed with the times. As with the best art, they're neither frozen nor ever really entirely finished but instead are alive.

Young is back working this turf because it suits what he has to say perfectly. In redoing the songs from Harvest and Harvest Moon he not only reimagined them, but also in a way recast his entire body of work or at least suggested other ways of looking at so much of it. This is not a renouncement of any sort. It's the celebration of an artist who's reached a place in his life that seems to be unusually spiritual and creatively peaking. A songwriter who's always offered visions has become visionary, the difference between experience and transcendence.

Every songwriter (every creative talent) has a voice. Not the real person, who goes to the bathroom, passes gas, and picks their nose, but the sensibility that authors their work. The voice might assume a character or many characters in the course of the work, but the voice is still dominant. Some artists have more than one voice. Most artists explore relatively limited territory especially in the way they use their voice. This is not a criticism.

Young is possessed of any number of voices. His is such a rich range of voices – multidimensional, distinct, and interwoven – that sometimes they're so far apart you'd insist they have different creators. Sometimes they're so close together it's hard to completely distinguish them.

There's Young as the tortured romantic, a personal voice telling tales of his own life, of love and dreams, failed and successful. Then there's Young the reporter, who, through the profoundly warped refractor at his center, comments on what's going on around him often in the most densely metaphoric way. There's the teller of history, sometimes an observer, sometimes a participant, sometimes a blind, near mad prophet. There's the mytho-poetic Young, almost at one with the biblical prophets in terms of encompassing morality, combing history with vision, sweeping down as though detached from any songwriter or band – as though being howled by the wind. The last voice is a variant on the one before it, but I think it's much more as well. It's when Young assumes his identity as a Canadian, an outsider in this country, an almost uninvolved spectator. When he's really taking the plunge into space, where he should fall but, superherolike, discovers he can fly, he celebrates Canada; he evokes its past, present, and future as one dealing with Canada and its people both as a country and a way of making meaning.

Then there are the ages of the observers never to be assumed or taken for granted. Sometimes they're young. Since the beginning, many of his songs have been written from an old person's point of view. A song like "Old Man" was once a 24-year-old thinking about someone much older. He's no longer that young man, but he's still not quite the old one. The song slides along his life assuming different meanings and tones.

Young's entire body of work, the songs, music, themes, visions, and meanings came home again and again during the show. Not only was the circle unbroken, but so many unfinished circles offered over the years were completed.

The most important moments were nonmusical. Neil and Pegi looking at each other smiling gave the songs and the whole damn performance a context so much greater than itself. Less noticeable was how, in between the songs, when the stage lights were off, so many different longtime members of the Neil Young family walked over to the side of the stage to wave hello and make eye contact with Neil and Pegi's son, who was sitting off of one aisle.

In one of the more mundane moments of music is where it all exploded for me. Young performed "Old King" from Harvest Moon, a tribute to a deceased bluetick hound. The first night, the run-through, he introduced the song by saying that here is where he'll tell a story. The second night he offered a long, rambling reminiscence, addressing it personally to Emmylou Harris, who sat with her guitar next to him. Young played banjo.

The last night he reworked it, playing a driving banjo riff as he talked about his dog. Finally I caught a lyric I'd missed. When there's so much magic in the more mundane, think about the revelations in the magnificent. Young sang:

"King went a-runnin' after deer.

Wasn't scared of jumpin' off the truck in high gear.

King went a-sniffin'

and he would go.

Was the best old hound dog

I ever did know.

"That old King was a friend of mine.

Never knew a dog that was half as fine.

I may find one, you never do know."

I've been writing about the films of Jonathan Demme, exploring his directorial sensibility, for months. One of the most astonishing things about the concert for me was realizing that Young is mining the same themes and maintaining the same very human sensibility that's consistent throughout Demme's work.

Earlier in his career, Young's work was much darker. Interestingly he started out deep and dark, then worked his way towards the light. To a much much lesser extent, Demme's career floated in the other direction. Starting off with a firm belief in the equality and potential of all of us, there's a real commitment in his work to celebrating human integrity and community as powerful forces. Later in Philadelphia, Beloved, and Manchurian Candidate, and in a very different way The Silence of the Lambs, Demme is still focused on the human community and by the possibilities of the individual alone as well as the triumphs of social cooperation. It's just that in these films he's so much more conscious of the quicksand traps and sudden tragedies of everyday life.

But in Demme's work, always, and in the way Prairie Wind reshapes the Harvest trilogy in Young's, there's now a certain quiet, fully informed optimism. Young missing his dog, comments: "I may find one, you never do know."

Not the grandest of ambitions, offered without self-pity or self-aggrandizement. This represents a tone of normality that mixes acceptance, rebellion, belief, hope, and awareness not as floating spiritual values, balloons in the Macy's parade of organized religion, but growing out of the way people are and how they lead their lives. This is about the bad things in life as well as the good. Life is tough, often brutal, and sometimes tragic. There is death, illness, loss of friends, the idiocies of some governmental agencies, accidents, wrecks, failures, loves that turn to bile. But there are also good times, family, and work.

Optimistic is probably the wrong word. It's more like maintaining faith even in the face of experience, history, and the odds. A faith rewarded only reasonably rather than mythically. In a time when so many American artists are shamelessly anachronistic ("Oh the past, it was so much better") and often militant fundamentalist Chicken Little apostles ("The sky is falling, the future is doomed"), even a small stand in favor of possibility is heroic.

Given our current governmental leadership, enthusiastic optimism would clearly be clinically insane. But having someone trust in the future, a trust neither naive nor unwitting, expectations for nothing colossal – actually for nothing except a stubborn insistence on living and not just living, but living as creatively and interestingly as possible – is of vital importance.

Young seems to have achieved some kind of peace, finally accepting that the past is alive and does haunt the present, but is finally, also past.

The memory at the end is like the closing shot of any number of silent films: Neil and Pegi Young smiling at each other, captured in a heart-framed focus that tightens in on them until there is nothing left but their faces.