In Memoriam

The Austin State Hospital Cemetery is the long final home for thousands

By Cheryl Smith, Fri., May 27, 2005

A motorist barreling east on North Loop is unlikely to notice more than a hint of the lonely vibe that emanates from the earth between the edge of the tiny strip mall called Highland Plaza and the bend in the road where the funky shops start. The chain-link fence of the Austin State Hospital Cemetery – 11 flat acres full of forgotten people – stretches almost the entire span. Little more than the empty space is visible from a car window – a couple-dozen grave stones, and the brown wooden sign on the fence that identifies the graveyard. That's about it.

Yet the reality of the empty space might make the passerby pause: Over more than a 100-year span, about 3,000 people have been buried there. Few of the graves are marked with a name, and nearly all are occupied by the bones of somebody who died indigent and whose family didn't claim him or her for burial, for one reason or another. "In many instances the families either ignored the [death] message or said they didn't want the person's body," said Sarah Sitton, a professor of behavioral and social sciences at St. Edward's University and author of a book about the hospital, Life at the Texas State Lunatic Asylum, 1957-1997 (Texas A&M University Press, 1999).

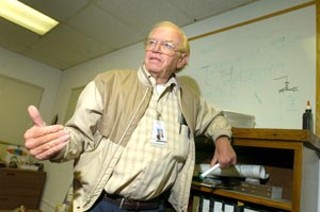

Times have changed. Among other things, the moon – luna in Latin – is no longer commonly believed to make a person a "lunatic." The asylum was politely renamed Austin State Hospital in 1925, relatives of the deceased have been receiving a phone call instead of a letter for many years, and students of the Austin State School, Texas' original institution for the mentally retarded, are now also laid to rest in the graveyard. Much, however, has remained the same. For years, corpses have been lowered into the ground in a state-issued pine box. The families of the deceased are almost always poor. And sometimes the person has no living relative, or the family simply doesn't want him, or her, anymore. At times, conceded ASH Maintenance Director Dave Rupe during a tour of the grounds, the family attitude has been, "We'd like to have them buried with the rest of them out there."

The lack of landscaping – only a few trees mark the otherwise grassy expanse – combined with the many graves distinguished by nothing more than a small, numbered, concrete slab, made a strong impression on Rupe the first time he crossed the cemetery in early 1998. He had been told that overseeing the graveyard was one of his responsibilities, so after a few months on the job he drove over and wandered around. "The more you look, the more you see. ... You begin to recognize very, very quickly that what you've got is society. The cowboys are there. The doctors are there. The teachers are there," he said. Mental illness "is not confined to any age group, any sex, any culture. It gets everybody."

Dallas Pioneer

One of the first people buried in the Austin State Hospital Cemetery was John Neely Bryan, the founder of the city of Dallas. When teachers and parents take Dallas schoolchildren downtown to see a heavily restored version of the cabin in which Bryan lived in the mid-1800s, the children hear a lot about the pioneer who sold parcels of land for $1 to anyone he could get to move to the area that eventually became Dallas. The kids typically don't learn, however, that Bryan was a longtime alcoholic and spent the last year of his life in the asylum. In 1882, Bryan's body was one of a roughly estimated 50 moved from the asylum's small original cemetery on the institution's sprawling grounds between Asylum Avenue (more familiar now as Guadalupe), Lamar, 38th Street, and North Loop, at that time the far outskirts of town. At one point, the asylum's grounds sprawled more than 1,000 acres and included a big pond as well as a dairy farm (now occupied by UT's intramural fields), and a hog farm, which only recently became the Triangle, now sporting a new mixed-use development across Guadalupe from the intramural fields.

The asylum's administration established the current cemetery when they decided to expand their facilities and build over most of the original graveyard, near what is now the main ASH building on Guadalupe. All of the bodies were supposedly dug up and moved to the new graveyard. Sitton, however, says that when she was researching her book, a hospital employee told her that not every corpse might have been removed. "There're stories from the grounds crew about digging up human remains when they're trying to plant a new plant," she said. Grounds maintenance supervisor Joe Williamson said he isn't aware of any such incident. "I think it's just a tale," he said.

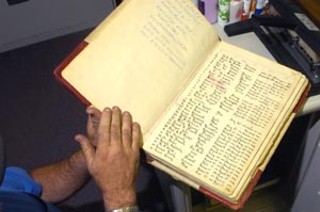

For those bodies that did certainly make the transition, each was said to have been wrapped and buried in a shroud, and their graves marked with a wooden stick inscribed with their patient identification number. If those sticks ever existed, they have long since rotted away – all anybody knows about Bryan's final place of rest is that he and the other bodies from the old cemetery are probably somewhere in the new one's southeast quadrant, perhaps idly monitoring the condominiums currently under construction on the other side of the east fence. Bryan is believed to lie in the southeast quadrant because remnants of really old headstones are visible there, Rupe said. Record-keeping was less than stellar at the time of Bryan's asylum stay, and some that were kept have since been lost. The calligraphy entries of the hospital's cemetery log begin in 1938. Bryan's name and the fact that he came from Dallas County are listed in a separate death log.

Giving Something Back

Austinite John Neely Bryan, great-great-grandson of Dallas' founder, wants to locate his namesake's corpse with ground-penetrating radar, have it DNA-tested, and rebury it in Downtown Dallas by the cabin. The plan is the end of a quest he embarked on a couple of years ago, after returning from a family reunion in Dallas. Bryan grew up hearing all kinds of stories about his ancestor, including one that he had died at the lunatic asylum and was laid to rest somewhere in Austin. As he was standing in front of Dallas County's old red courthouse visiting with family members, he learned that some had in years past unsuccessfully attempted reviewing records from the hospital, hoping to discover the burial site. "I said to myself, 'I'm going to look into it and see what I can find,'" Bryan said.

As fate would have it, after he moved to Austin in 1995, Bryan, a financial analyst, had become involved with the Austin State Hospital Volunteer Services Council, and was a council board member by the time of his family reunion. Bryan didn't tell anyone affiliated with the hospital or the council that his great-great-grandfather was likely buried in the ASH cemetery. He says he was grateful to the hospital for having taken care of his ancestor during his last days, but he didn't want his ancestry to distract from his volunteer work. "I just thought I'd give something back," Bryan said. After the reunion, however, Bryan knew he was going to need some inside help to find out more about his great-great-grandfather, so he told Rupe about his personal tie to the hospital: "That's when I let the cat out of the bag."

As it turned out, the cat was already on the loose. "People knew but never really talked to him about it," said Rupe of Bryan's ancestry. The passing of more than a century, plus the fact that the elder Bryan had been committed to the asylum for alcoholism – widely accepted today as a disease rather than a personal weakness – apparently hadn't entirely lifted the taboo of having died in a mental institution.

Outside the Box

ASH maintenance technician John Classen has been the cemetery's cement headstone maker for 18 years. His casting work changed significantly after Rupe came along. All ASH Cemetery headstones made since 1998 have included a name, date of birth, and date of death. For more than 60 years prior, graves had been marked only with a 4-inch-by-12-inch numbered slab – most have long since sunken into the ground and barely peer from under the grass. One day Rupe told Classen that the cemetery needed a new headstone, and then added, "This time we're going to do it with a name." Classen was surprised, but recalls replying with a resolute "'Good.' The numbers were so small and impersonal," he said. "I was glad to see the change."

The change had already been made to the state's legal code. A 1991 amendment to the Health and Safety Code had made it legal for superintendents of residential care facilities to release to cemetery and funeral home representatives the name, date of birth, and date of death of any person who had lived at the facility, unless the person or the person's guardian had objected in writing. The amendment also made it legal for cemeteries and funeral homes to inscribe the information on grave markers. "That may be one of those deals [where] I don't think anybody ever really thought outside of the box," said Williamson, the ASH grounds supervisor, of the administration's attitude toward the cemetery. For years, family members of people buried at the cemetery had occasionally been buying regular tombstones and having them placed by the state-issued slab of their relative. These are the markers that rise above the short grass and are visible from the street.

An integral part of the hospital's culture was, and to a large degree still is, that the world behind the facility's doors was not acknowledged beyond them. About a mile from the hospital, the cemetery has always been far beyond those doors, and largely out of mind. Take the work experience of Carl Schock, ASH's superintendent since 2000, as an example. Schock said that as a mental health worker at the hospital in the late Seventies and early Eighties, he was completely unaware of the cemetery's existence. It wasn't until he left the hospital for a few years, then came back as director of nursing in 1997, that he heard about the graveyard. He never actually went there until after he became superintendent. The long-overdue walk through the sunken slabs provided him with a perspective unavailable from inside the hospital. "You kind of get a feeling – kind of a mix of the history and all the things the people dealt with," Schock said. "Even in death, we've neglected to deal with the issues of mental health over time."

Making Plans

There are a couple of myths about the cemetery that Rupe would like to erase. First, no bodies are buried above one another, he says, despite the fact that the practice is legal in Texas. (At least one row of the cemetery, however, is dedicated to random body parts. From the late Fifties until the early Nineties, the hospital included a medical treatment facility for surgeries and autopsies. For lack of an incinerator, body parts were disposed of at the cemetery.)

Secondly, just because someone died at the hospital doesn't necessarily mean he or she was buried at its cemetery. About a third of the patients who died in the asylum from 1861 to 1925 were buried in the cemetery, Rupe said; the rest were taken elsewhere by their families. The same holds truer for modern times, largely due to the prevalence of pre-death planning. Although students of the Austin State School are also now laid to rest in the cemetery, in recent years there have only been about two or three burials annually. Austin State School Superintendent Ray Wells says that most of his 400-plus students are covered by preplanned burial plans. "It's good to have available," said Wells of the cemetery. "But nowadays, that's what we do – preplanning through our social workers and families."

The Austin State School began using the cemetery after the Travis State School, another locally based school for mentally retarded citizens, closed in 1996. Travis had a large graveyard shared with the Austin State School. According to ASH cemetery records, more students from the state school are now buried at the cemetery than patients from the state hospital, not surprising since the average stay at the state hospital these days is only a few weeks, compared to several years at the state school. Seth Adam Armstrong, an Austin State School student born in 1973, has the most recent burial date at the cemetery, October of 2004. The last burial before Armstrong, in Febraury of 2004, was that of Reggie Davidson, who was 98 years old and spent 88 years of his life at the state school.

Finding the Missing

Back at the hospital's maintenance building, Rupe is working on two big cemetery-related projects. A huge map of the cemetery covering part of a wall in the break room records one of them. John Neely Bryan isn't the only one who wants to use ground-penetrating radar in the graveyard. Rupe estimates there are about 700 bodies that aren't accounted for in the hospital's cemetery log, and he wants to find them. He also wants to determine if there was an overall burial plan in the graveyard, or, as he put it, "if there's rhyme or reason to the plot pattern."

He already knows one major piece of the puzzle. The cemetery was racially segregated until the 1960s – the north end racially divided by row, and the south end divided in half, one part for whites, the other for blacks. There's a strip through the middle of the grounds that's not full of bodies, Rupe says, that can hold about 1,000 more.

Rupe began his other project, creating a patient records database, about three years ago. Thus far, he has 11,400 names on file in the computer on his cluttered desk. The entries of individuals who died in or after 1903 tend to be fatter than the earlier ones, since death certificates weren't issued in Texas before then. Record keepers listed cause of death prior to 1903, but the causes were usually vague – "heart failure," or "softening of the brain."

Genealogy led Rupe to both projects – not his own roots, but those of others. (He hasn't had any family experience with mental illness and isn't aware of any in his family tree.) People contact him regularly with inquiries about relatives. "The vast majority of them don't care why they were buried here," he said. "They just want to know where their relatives are."

Thanks in large part to the Internet, genealogy has grown significantly in popularity in recent years. Rupe describes his projects as "an outgrowth of this genealogy." So is yet another project under way. This one is at the cemetery – a mostly volunteer effort to spruce up the grounds. So far, the project has generated fancy wrought-iron front gates facing 51st Street, a few limestone columns that volunteers would like to see extend from the gate all the way to the east end of the graveyard, and a paved driveway stretching from the entrance. The project is one of several nationwide, as genealogists all over the country have been trying to trace the lives of lost relatives, and in the process, have seen the condition of mental hospital cemeteries across the U.S. There was, and is, nothing unique about the anonymity of Austin State Hospital Cemetery.

In 2002, the graveyard received Historic Texas Cemetery designation, so there are plans for a commemorative plaque. And this Friday, three days before Memorial Day, Rupe, other hospital employees and volunteers will honor the cemetery's occupants by peppering the grounds at 1pm with 3,000 little American flags. Last year was the first time anything like that had ever been done there.

"When he first came up with that idea, we thought, 'He's lost it,'" said Williamson, who has worked for the hospital since the Seventies. "I thought it was kind of strange. After you thought about it, it made sense. Why not?" ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.