The Rumble at Bunny Run Heads to Council

Neighbors say school reneged on promise of no apartments

By Rachel Proctor May, Fri., Feb. 18, 2005

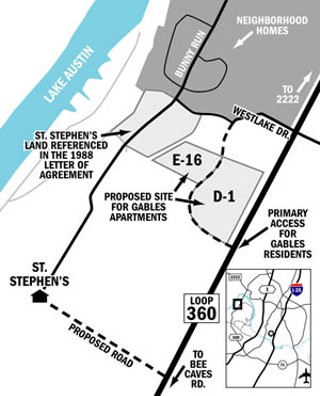

For a larger map click here

Signs have been popping up recently around Bunny Run, a pricey neighborhood nestled between Highway 360 and a tight bend in the Colorado River in northwest Austin. The signs are white, and in blood-red letters they warn, "Our neighborhood is at risk."

That risk is in the form of a 323-unit apartment complex proposed by the Gables Residential real estate company but opposed by many in the neighborhood. Call it the Rumble at Bunny Run: In one corner is Gables and St. Stephen's Episcopal School, which wants to sell 32 acres on which to build the complex; in the other is the Bunny Run Neighborhood Association, which is fighting for its right to keep the neighborhood free of apartment complexes. The issue goes to City Council for a public hearing today (Thursday), although on a heavy agenda it may be postponed.

This is no straightforward zoning battle, in which stakeholders argue over what everyone wants for today and the future. Instead, they also have to argue over what everyone wanted 17 years ago, when St. Stephen's either did or did not agree to keep its land apartment-free in perpetuity. Because of that history, some of those involved consider it a test case of the city's commitment to neighborhood control over long-term planning.

The story begins in 1988, when Davenport Ranch was developing a planned unit development, or PUD, for a 2.5-mile strip of Highway 360. Within a PUD, various parcels of land are simultaneously zoned for various usage categories, such as single-family or commercial, a process that in theory allows all affected parties to agree what kind of development will work best in what place.

St. Stephen's owned about 400 acres surrounded by the PUD; the Bunny Run neighborhood was its western neighbor. Neither wanted commercial development in their back yard. (Not all this land is affected by the dispute.) But, says Tom Burns of the BRNA, when the neighborhood learned that the PUD was slated to include over a million feet of commercial development just north of Wild Basin, within a breeding ground for the endangered black-capped vireo, the neighbors conceded. The BRNA agreed to support plans to build a commercial development at the corner of Westlake Drive, the primary intersection for entering and leaving Bunny Run, so the city could buy the land previously slated for commercial and make it a vireo preserve. "Of all of the parties, there is no question that Bunny Run was the most altruistic," Burns said. "We sacrificed our personal interest for the good of the city."

The neighbors' only stipulation, he continues, was that there be no multifamily development in the entire PUD. On Nov. 1 and 2, 1988, the neighborhood signed letters of agreement with Davenport Ranch and with St. Stephen's, stipulating only single-family houses could be built on the land closest to Bunny Run.

However, these agreements as executed don't actually apply to the entire PUD. Excluded are two of St. Stephen's tracts, 32 acres of land known as blocks D-1 and E-16, just south of the Westlake intersection. According to Brad Powell, business manager of St. Stephen's, this was intentional. "Our board purposely would not agree to a restriction on that piece of property because we wanted to make sure the value of that property was maintained in the future," he said. In other words, the board wanted the discretion over how the land would be developed.

So the PUD was approved, with blocks D-1 and E-16 zoned for office space. If St. Stephen's were to find a buyer to develop the land under the existing zoning, the result would be four huge office towers, with significant loss of trees and leveling of the land. The Gables project is preferable, says Powell, because it preserves more trees and more of the land's natural grading, and the buildings will be less visible and generate about 60% less traffic.

But the neighbors oppose multifamily. They say they need more retail in the neighborhood, and they argue that even if apartments generate less trips overall, they will cause more rush-hour traffic at the Westlake intersection, which is already jammed solid with commuters on weekdays. Above all, the BRNA argues that the zoning laid out in a PUD reached through months of negotiation should be honored. "We believe that what we walked away with in 1988 was a long-term plan," said Burns. "The issue for us is neighborhood predictability."

This view swayed several members of the Zoning and Platting commission, but not enough for the neighborhood to prevail: In January, the commission voted 5-4 to recommend that council approve the zoning change to multifamily. Steve Drenner, the lawyer representing the Gables, argues that it's absurd for the neighbors to say they thought the 1988 zoning decisions were binding. "There's nothing permanent about zoning," he said. "Under Texas law, it's actually illegal to zone permanently. It's always left up to the discretion of future city councils."

In short, all the fuss over what happened in 1988 boils down to one basic question: If St. Stephen's and the BRNA did agree that there could never, ever be multifamily on tracts D-1 and E-16, why didn't the neighbors get it in writing, rather than signing an agreement that only refers to half of St. Stephen's land?

In addition, the council must also decide whether the Gables have sufficiently addressed the neighborhood's 2005 concerns, particularly those about traffic. Gables has agreed to build entrances that will direct both St. Stephen's and Gables traffic away from the Westlake intersection and directly onto 360. Gables has also offered to pay to add extra lanes at the Westlake intersection. These measures have impressed Skip Cameron, who as president of the neighborhood coalition Bull Creek Foundation has fought many development battles, including some with Gables Residential. "Most of the arguments I'm hearing have to do with traffic," he said. "That's nuts. The development would move traffic away from Bunny Run."

Cameron says the BRNA is offering "fictitious" arguments to cover up for the fact that the affluent residents simply don't want renters for neighbors, and are refusing to make a reasonable compromise. However, Susan Pascoe, president of the Austin Neighborhoods Council, which has signed a letter of support for the BRNA, believes that neighborhoods shouldn't have to compromise after their plans have been adopted. She sees a disturbing trend in which carefully honed neighborhood plans are nibbled away by the city via grants of variances and zoning changes. "We have neighborhoods come to us all the time, saying that developers have asked for something that is not in the neighborhood plan, and gotten it," she said.

However, neighborhood plans are formal, signed agreements with the city. The closest parallel in the Bunny Run case is the 1988 agreement which, unfortunately for everyone involved, doesn't make any specific reference to blocks D-1 and E-16.

In the end, says Burns, the case is a litmus test of whether the city cares more about developers or regular citizens. If the BRNA loses and the Gables is built, he says, Austinites will know there's no reason for regular folks to bother participating in zoning and planning discussions, or to make sacrifices for the good of the environment. But Cameron believes that the current zoning process, in which land use is periodically debated in a public venue with all interested parties at the table, is a fine example of democracy in action.

"What we've learned over 12 years of working on these issues is, if a coalition of interested people band together, and you have good ideas and solutions that are better than what's being offered, and have dialogue with developers, you can have a great deal of impact on how developments are planned," he said. "Citizen groups can get what they want through the bureaucracy, if they work at it."

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.