Wrong Place, Wrong Time

Texas prosecutors use the 'law of parties' to widen the net for capital punishment

By Jordan Smith, Fri., Feb. 11, 2005

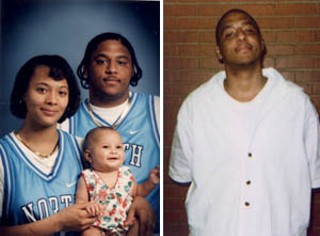

(Photo courtesy of the Foster family)

Around 9pm on Aug. 14, 1996, 19-year-old Kenneth Foster and three companions – Julius Steen, Mauriceo Brown, and Dwayne Dillard – got into Foster's rental car and headed into downtown San Antonio. Foster, born in Austin but raised in San Antonio, was a college student and aspiring rap musician trying to launch his own label, Tribulation Records. He'd only recently been introduced to Steen, who had a similar passion for rap, and Steen in turn introduced Foster to Brown and Dillard. For a couple of hours, the four young men drove around the city, cruising local music clubs. At 11:30pm, Steen later testified, they were still driving around, when Brown brought out a gun. "He said, 'I have the strap, do you all want to jack?'" – meaning, Steen explained, "approach someone that we do not know and commit a robbery."

According to Steen, the others agreed, and in a little over an hour the four men had committed two similar robberies. Twice, Steen spotted and chose a victim; Foster stopped the car; Steen and Brown pulled bandanas over their faces and, with one of them brandishing the gun, approached and robbed the marks. From the two crimes, they scored about $300.

After the second robbery, Dillard would testify nearly four years later, Foster wanted to stop. Foster asked Dillard to convince Steen and Brown, because Dillard knew them better and Foster thought they would dismiss his own hesitation. The four drove on, looking for a club Foster wanted to check out on the way home – but he got lost north of downtown, and wound up on a dark road in an unfamiliar neighborhood, driving behind two cars. Thinking the cars might be headed to a party, Foster continued behind them, until they pulled into a driveway leading up to a darkened house. Foster drove a short distance more before turning around. When the four passed the house again, they were surprised to see a woman standing at the foot of the long driveway, gesturing to them.

Brown wanted to stop and check things out – especially the young woman. "Kenneth [Foster] had stopped and Julius [Steen] rolled his window down. And she was ... like, 'Well, why the hell are you following us?'" Brown testified. "And Julius was like, 'We wasn't following you.' ... [S]he started cussing at Julius. And Julius said, 'I am not trying to hear you,' and he rolled up the window," Brown continued. "While she was walking away, she was like, 'Well, you all just like what you all see. Take a picture, it will last longer,'" he said. "I wanted more than a picture, I wanted her number. So, I got out of the car." Indeed, as Steen rolled up his window, Foster started to drive away, he said, and had to stop quickly when Brown's door opened.

The three men waited in the car while Brown followed the woman, later identified as Mary Patrick, up the driveway – more than 80 feet away from Foster's car. Then, Foster said, he heard a gunshot: "I sprung up [and] hit the gas – it was more reflexive than anything else," he recalled, as Brown ran back to the car. "[Brown] gets in the car [and we say], 'Hey man, what happened?' He was catatonic." Foster drove away.

There are several different accounts of what happened in the driveway, but undisputed is that the encounter left one person dead. Patrick's boyfriend, Michael LaHood Jr., who had apparently been standing near his car when Brown made it to the top of the drive, had been shot through the head at close range. LaHood lay dead, face down on the concrete driveway outside his parents' home.

Within an hour, police arrested Foster, Dillard, Steen, and Brown.

Later that morning, Foster's grandfather, Lawrence Foster Sr., with whom Foster lived for most of his childhood, saw on television what he thought might be the white Chevy Cavalier he'd rented for his grandson. He called Kenneth's cell phone several times. Finally, a police detective answered and told him that Kenneth had been arrested for murder. "I didn't think it was that bad," he recalled. "Knowing [Kenneth], that's not ... something he'd do. ... I thought they'd drop it."

He Should Have Known

Lawrence Foster Sr. was wrong. On Oct. 11, 1996, Foster, Dillard, Steen, and Brown were each indicted on capital murder charges by a Bexar Co. grand jury for "intentionally and knowingly" shooting LaHood while trying to rob him. As unthinking and reckless as were the young men's actions that night, the state's response seemed at least equally arbitrary and illogical. For Foster and Brown together, the state sought the death penalty, and got it – after a five-day joint trial beginning in late April 1997, a jury sentenced both men to death. Steen, who had served as a lookout earlier that night, cut a deal with the state to testify against the others and was thereby spared the possibility of a death sentence. Dillard was never tried for the crime, but was held under indictment until shortly after Foster and Brown were convicted, and so was unavailable to testify at their trial. "[Dillard] refused to participate at all and didn't want to make a deal with the state," said Michael Ramos, who prosecuted Brown and Foster.

Indisputably, Brown had been the shooter – and he did not deny it, although he argued that he fired the fatal shot in self-defense, believing that LaHood was reaching for a gun tucked in his waistband. No second gun was ever found. Nor did anyone contend that Foster played any direct role in LaHood's death, although he was charged with capital murder. Prosecutors sought death for Foster under the state's "law of parties" – a statutory procedure that allows the assignation of guilt to secondary actors in a crime.

Under the law of parties, the jury was not required to find that Foster had any part in – nor even any intention of – harming LaHood; instead, all that the jurors needed to conclude was that Foster should have anticipated that Brown's actions might result in LaHood's death. At trial, prosecutors argued that Brown's actual intention that night was to rob LaHood – just another "jack," like the two previous ones – and not simply to score Patrick's phone number. The "entire reason" the four were out that night was to commit robbery, Ramos said. And since all four were responsible for the earlier robberies, the state argued, by law they could be held responsible for Brown's actions, even though they played no active role in LaHood's death. Under this theory, the state did not have to prove that Brown intended to rob LaHood – by law, evidence of the previous robberies was enough to suggest there was a plan to rob LaHood, and thus, enough to suggest that, using the "reasonable person" standard, the killing was foreseeable. "When you were out that night did you think that somebody could get killed?" prosecutor Jack McGinnis asked Steen in court. "There is a possibility, yes," Steen replied.

Foster's defenders say the prosecution's theory is absurd and unjust, and that his case is a textbook example of the large and potentially deadly problem with the Texas law of parties. Specifically, they argue that a section of that law – section 7.02(b) of the Texas Penal Code – unconstitutionally makes a defendant eligible for the death penalty based only on tangential involvement in a crime, indeed, for being at the wrong place at the wrong time. The law's threshold for proving culpability is so low, and the discretion prosecutors have to decide its application so wide, critics say, that the law unconstitutionally expands the pool of death-eligible defendants, instead of ensuring the ultimate punishment is reserved for the most heinous crimes. "There are many more people who commit murder by their own hand than are caught in the death penalty net," says UT law professor Jordan Steiker. Supporters of capital punishment generally insist that the death penalty is reserved for "the worst of the worst." If that's true, asks Steiker, "How can someone be eligible in this vicarious way?"

Ripe for Abuse

Most observers, even those who accuse prosecutors of abusing 7.02(b), agree that the law must prescribe some way to hold parties to a crime responsible for their conduct. Indeed, the law has long reserved that room. "The law of parties is a perfectly good legal statement of culpability in felony cases," including those carrying the possibility of a death sentence, said James McCorquodale, a Dallas attorney who has challenged the use of the law. "The reason that people keep wanting to [challenge it] in the capital context is that, aside from legal culpability, there should be [a weighing] of moral culpability."

Chapter Seven of the Penal Code outlines the ways in which a person can be held "criminally responsible" for the actions of another. Under Section 7.02(a), a person can be considered responsible for a crime committed by another if the person promotes, solicits, encourages, directs, or aids in the commission of a crime (a fairly common definition of accomplice liability), or aiding and abetting, which requires the state to prove specific, individual culpability. However, under Section 7.02(b) – the "conspirator liability" statute – if a group of two or more "conspirators" agree to commit one crime, but in the process commit another, each of the conspirators is guilty of the crime committed, if the crime was "one that should have been anticipated." The difference is one of intent and foresight: The "accomplice liability" standard requires a finding of intent, while the second, more broad and less rigorous conspiracy section simply requires a finding that a crime was foreseeable.

In practice, the two sections have often been applied by prosecutors – and by judges, in crafting the jury charge – as a seamless unit. "The whole shooting match ... can be given to a jury and left to them to sort out," says UT law professor Rob Owen. Thus, in Foster's case, the state offered jurors a descending scale of culpability upon which they could convict, and, in the end, assess death as punishment.

Hence, prosecutorial use of the law has created – not only in Foster's case, but also in numerous other cases tried since the statute took effect in 1974 – the possibility of a death sentence without any legal finding of active participation in a crime, nor even of a homicidal intent. To Keith Hampton, Foster's current attorney, who knows of many similar cases, that is a major problem. "By employing the conspiracy liability statute, the state is able to make persons death-eligible on nothing greater than a negligence standard – that the defendant 'should have anticipated' that his conspirator would, in the course of any planned felony, intentionally kill another person," Hampton wrote in Foster's federal appeal. That is true even though, he continued, "negligence is the least culpable mental state known to criminal law."

The most troubling aspect of the law is its reliance on "foreseeability," says Owen. "The problem is asking jurors to put themselves in the shoes of a person who has done something [where the outcome is already known], and to ask them to put that out of their minds," Owen said. "It is nearly impossible to ask someone to suspend their disbelief once they know what happened. That's a real problem. Lots of things, in retrospect, look like a bad idea." As a result, the law offers prosecutors wide latitude for attributing responsibility for a crime, and carries with it the potential for devastating, and ultimately unjust, results. "It is ripe for abuse," said Owen. "It is a standard that could be stretched to fit a lot of situations." Foster says that's exactly what Bexar Co. prosecutors did in his case. He admits his involvement in two robberies that night but denies that there was any connection between those crimes and the LaHood murder. "The fact that I let [Brown back] in the car," he said in an interview on Livingston's death row, "does not make capital murder."

"Knowing Engagement"

Since 1982, the U.S. Supreme Court has twice tackled the "law of parties" and its applicability in capital cases, with conflicting results. In a case styled Enmund v. Florida, the court ruled in 1982 that Earl Enmund's agreement to act as a getaway driver in a robbery that ended in murder was insufficient to warrant death. "Enmund did not kill or intend to kill and thus his culpability is plainly different from that of the robbers who killed," the court wrote. "We have concluded that imposition of the death penalty in these circumstances is inconsistent with the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments." The court concluded that in order to be eligible for the death penalty, a defendant either had to kill, attempt to kill, or intend to kill. The decision, says Owen, "seemed to be an honest attempt" to "screen out" a category of defendants as ineligible for a death sentence.

However, just five years later, the court reconsidered Enmund. In 1987, the court took up Tison v. Arizona, in which two brothers were sentenced to death for a quadruple homicide their father committed after the brothers helped him break out of prison. Although the brothers did not intend to kill, the court opined, their involvement in the prison break was substantial, and the cache of weapons they took along suggested they were ready to kill if necessary. "[K]nowingly engaging in criminal activities known to carry a grave risk of death represents a highly culpable mental state," the court concluded. "We will not attempt to precisely delineate the particular types of conduct and states of mind warranting imposition of the death penalty. ... Rather, we simply hold that major participation in the felony ... combined with reckless indifference to human life is sufficient to satisfy the Enmund culpability requirement."

The two rulings have not finally clarified the circumstances necessary to impose death for party liability – and as a result, Texas' broad statute remains intact. "Under Enmund, [Foster] should win [his appeal]," Hampton said. And even under Tison, he said, he thinks Foster should still prevail. Foster's jury was not asked whether Foster had "major involvement" in LaHood's death, only whether "he should have anticipated Brown's actions," Hampton argues. "Is that the same as major involvement? I don't think so."

"Contrary to Justice"

Whether Foster will indeed prevail is currently a question for the intermediate courts: the state Court of Criminal Appeals and, eventually, the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. Neither panel has heretofore shown much interest in a critical assessment, let alone a refining, of the state's law of parties.

On direct appeal, the CCA summarily dismissed Foster's argument that the state's evidence of his alleged involvement in the LaHood murder was insufficient to sustain his conviction, let alone to warrant death. "[E]vidence that a defendant drove the getaway car after a robbery has been held sufficient to convict the driver as a party to the offense," the court wrote. "Despite the fact that Brown's actions at the LaHood home did not seem to follow the group's regular pattern of committing aggravated robberies, it is reasonable to infer that Foster's did. As usual, he was the driver and just waited in the car. After Brown attempted to rob and then shot LaHood, Foster drove them away from the scene," the court continued. "Although there was conflicting testimony as to Brown's intent at the LaHood home, the jury was free to believe Steen, who said he 'had a pretty good idea' what was going to happen when Brown got out of the car."

Steen has since partially retracted that testimony. He told Foster's appeal lawyers that after Brown got out of the car he realized the potential for an altercation between Brown and LaHood, but that when Brown got out he had no idea what Brown was doing. During the trial, however, Foster's defense attorneys were unable to make that distinction – as part of a defense all too typical for a Texas capital case. Foster's court-appointed trial attorneys never interviewed Steen prior to his taking the stand, and when his appeal attorney Hampton finally talked to Steen in January 2003, it was the first time that any of Foster's defenders had ever questioned the state's star witness. "They were entitled to," said Ramos. "We never stopped them."

The CCA's reasoning was no surprise to Verna Langham, the attorney who handled Foster's first appeal, who says she received a similar ruling in a similar case more than a decade ago. Langham was the appellate attorney for Norman Evans Green, who was prosecuted as a party to the botched robbery of a San Antonio electronics store that resulted in the shooting death of 18-year-old store employee Timothy Adams. In 1985, Green agreed to rob the store with another man who intimated that it would be an "inside job," Langham said, and therefore was unlikely to involve violence. "The evidence, beyond a shadow of a doubt, was that Norman was not the shooter," she said. Still, at trial, she said, the question was whether Green should've anticipated Adams' death. "Did Norman know the other kid had a gun? Did he know there was a possibility that it would be used?" she asked.

Green was sentenced to death and executed in February 1999. In a separate trial, his accomplice (who Langham insists was the actual murderer) received a life sentence. "My guy was where he shouldn't have been, doing things he shouldn't do; but that's liability," she said. "Now there's Kenneth – Kenneth was where he shouldn't have been, with people he shouldn't have been with." That alone should not be enough to sentence someone to die, she said, but "the way that law is written ... it is subject to such loose interpretation. ... A kid in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong people can end up being sentenced to death."

Indeed, it is the "looseness" of the law that opens the door to a host of potential problems, said UT's Steiker, such as a shooter who agrees to testify against his getaway driver in order to avoid the death penalty. "There are a fair number of nontriggermen that get caught in the web, and the basic unfairness of it depends on who [cooperates with the state], and that turns culpability on its head," he said. "How can you just execute the lesser participant?"

(Photos courtesy of the Foster family)

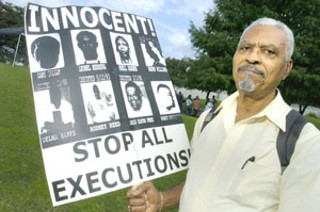

That is a question Dallas Municipal Court Judge Bonnie Goldstein has pondered for more than a decade. Goldstein (with McCorquodale) worked on the appeal of Mexican national Irineo Montoya, who was convicted as a party to a 1985 robbery and murder in Cameron County. Juan Fernando Villavicencio was arrested for the murder, confessed to the killing, and alleged that Montoya had actually restrained the victim while Villavicencio stabbed him. Montoya was tried first, convicted and sentenced to death based primarily on the testimony of members of Villavicencio's family, who claimed they'd been told details of the crime. However, the same witnesses changed their testimony at Villavicencio's trial, and he was acquitted of the murder, Goldstein said. "Welcome to Texas: The principal [defendant] was acquitted," she said. "It is disgusting and contrary to justice ... [when] the accomplice is punished more harshly." Montoya was executed in 1997 – just over a month after Foster was sentenced to die.

According to Hampton, it was the CCA's decision in the Montoya case that affirmed the state's current use of 7.02(b) in capital cases. On appeal, Montoya argued that the court erred when instructing jurors to consider the "theory of conspiracy" to determine Montoya's guilt, since he had never been charged with "criminal conspiracy" – a crime distinct from capital murder. The court disagreed, writing that the intention wasn't to "instruct the jury to consider whether [Montoya] was guilty of the separate offense of criminal conspiracy," but was offered "merely" as an "alternative 'parties' charge." The justices offered no further explanation, Hampton said, and to date has failed to elaborate, although the court routinely cites Montoya when dismissing similar arguments. "It was a little sleight of hand," he said. And now, they say, "'Well, we've been doing this since Montoya' – but it's been wrong since Montoya."

The Punishment Fits the Victim

Setting aside the legal arguments, in Foster's case there is a darker, more personal possibility that prosecutors intentionally used the law of parties to turn a simple homicide into a capital murder, in order to appear tough in a high-profile case in which the victim was the member of a prominent family. "It was on the news every day," recalled Foster's trial attorney Cornelius Cox. And everyone, it seemed, knew Michael LaHood Sr., and his son, the victim, Michael Junior – especially those in the legal community. The elder LaHood, a respected attorney, and his son, who had worked as a messenger, were fixtures at the courthouse.

Indeed, Lawrence Foster says the elder LaHood's notoriety made it difficult to find a local attorney with whom he could consult on his grandson's case, and in court LaHood's status appeared to earn his family questionable favors. Foster says lawyers told him, "'I wouldn't touch that case with a 10-foot pole, I'll never get any cases again.'" During the trial, he continues, "I would see [LaHood Sr.], in the judge's chambers, talking to the judge. I looked back there to make sure they saw me. I asked the secretary, 'Can I talk to the judge?' She said no."

Prosecutor Ramos denies that LaHood's local status played any role in the decisions made by the district attorney's office. The decision to seek death for Foster was "ultimately made by the DA and [his] assistants," he said. "My input was little, if any, although I was in favor of it." The Bexar Co. DA's office treats "every case the same," he said, adding that if there had been any favoritism at play, the office "would've sought the death penalty for all four of them." As it was, Ramos says the state chose to prosecute the two defendants they believed were "the two most culpable individuals."

Even without favoritism, Foster and his defenders insist, the state still abused its discretion by seeking the death penalty. Foster admits that he was wrong to participate in robbing people, but vociferously denies that he knew or should have known that LaHood's life was at risk. He was young and stupid, he says, but does not believe that he should pay with his life. "It's like I was in the tadpole stage," Foster said, "and I got stuck in making the transition." Lawrence Foster says he will continue to fight for his grandson, calling him a good kid who did well under his grandfather's tutelage – no small feat in itself.

Kenneth Foster's parents each had crippling drug habits that darkened their son's early years. Kenneth was born at Brackenridge, and until the fourth grade lived in East Austin near Rosewood and Hargrave streets. His mother "ran the streets, prostituted, and died of AIDS in 1993," Kenneth quietly recalls. His father, Lawrence Foster Jr., took the boy with him to "dope houses" where he scored and used heroin and crack. Foster's grandfather says Kenneth's parents regularly used their young son as a "shield" when shoplifting to support their habits. "They'd go to the store and steal items and put him in their arms or in a basket and [use Kenneth to] conceal it."

Lawrence Foster Sr. says he often wanted to bring Kenneth to San Antonio to live with him and his wife, Eleasie, but didn't know if he should force the issue. "I would come up through [Austin] and go by [their house] and leave money or clothes or whatever I had to help," Lawrence recalls. In hindsight, he says, "I know they didn't use it to his benefit." Eventually, when Kenneth was in the fourth grade, he did go to live with his grandparents on the far west side of San Antonio. "He liked it down here. ... He became more stable," Foster says. "I didn't ever like him going to visit [in Austin] because he'd come back and have the same traits [as his parents], and I wanted to eradicate them. He'd steal things and not know any better." Kenneth had several run-ins with the law, including a couple of minor drug possession busts, but he was more good than bad, and Lawrence Foster intended to keep it that way.

Lawrence, an educator for more than 30 years, pushed Kenneth to do well in school and to keep himself on track. "I did what I could," he says. "Kenneth holds me in high esteem, he's said. ... And he thinks that [his grandparents] are the reason he is what he is – not where he is." Indeed, Kenneth says he doesn't really understand why he is "where he is," on death row. "If I'd made a left turn instead of a right turn," he says, recalling that summer night in 1996. "It must be for a reason."

For now, Kenneth believes he is supposed to fight for fair treatment under law – and for an end to Texas' current law of parties. In 2000, Kenneth helped start the anti-death-penalty activist group Visions for Life to work on behalf of death row inmates who "never should have received the death penalty" – including mentally retarded and juvenile offenders, and those convicted under the law of parties. "This is not about Kenneth Foster; it's about this crooked statute," he said recently. The death penalty is supposed to be "reserved for the most heinous crimes." But under 7.02(b), "everybody's a Ted Bundy."

Kenneth Foster's appeal is currently pending in federal district court, where it has waited for nearly two years. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.