2004 Texas Book Festival Preview

The 2004 Texas Book Festival

Fri., Oct. 29, 2004

Chango's Fire

by Ernesto QuiñonezRayo, 273 pp., $23.95

Upon the publication of Bodega Dreams, his 1999 debut, The Village Voice dubbed Ernesto Quiñonez a "writer on the verge." With Chango's Fire, his second novel, Quiñonez shows that he is no longer on the verge, but has crossed over as an accomplished storyteller with all the respect and gifts the title confers.

Julio Santana is the novel's anti-hero. By day, he's a hardworking student, a good son to his aging parents, and self-appointed guardian to a mentally challenged friend. By night, he works as an arsonist for hire, the grunt in an insurance-fraud scheme that has made many rich in the name of progress, and provided Julio a comfortable lifestyle. When Julio decides to quit his secret work, his employers are dangerously displeased. Complicating his dilemma is his involvement with Helen, a white woman who challenges his assumptions about home, entitlement, and the limits of his heart.

While Chango's Fire first appears to be a life-on-the-mean-streets novel, tackling several large issues – urban gentrification, racism, class – Quiñonez examines them in the palm of his hand, distilling them to extract their power, leaving the reader with a distinctive and surprising bouquet that lingers long after the novel closes. – Belinda Acosta

Sunday, Oct. 31, 1-1:45pm, Capitol Auditorium CE1.004

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

Shambles

by Debra MonroeSouthern Methodist University Press, 201 pp., $22.50

All Delia Arco wants to do is raise her adopted daughter, Esme, with limited interference from the outside world. Unfortunately, the outside world can't seem to keep to itself, and Delia is barely able to keep chaos at bay. Almost everyone who wanders into Delia's life is wounded or scarred in some way, be it the student intern whose parents were murdered, resulting directly in the derailment of her psychic train; the lesbian neighbor seeking female solidarity; the itinerant lover with the tumor on his back; or her father, who shows up unannounced with a time bomb ticking in his innards. The lonely yet independent Delia constantly finds her boundaries tested, her nerves stretched too tight, and her mind increasingly, well, in shambles. Catastrophe after catastrophe forces the single mother to rely on those who would encroach upon her poorly built hermit shack; she learns the hard way that the distance between self and other isn't all that far to travel. It's difficult to parse Debra Monroe's writing, although it's not hard to believe that this is intentional on her part. The easy explanation is that the writing is simply awkward; as the narrative progresses, however, it seems as though Monroe, a writing instructor at Texas State in San Marcos, is attempting to portray the slightly numbed discombobulation of real life. If this is indeed the strategy, it is only halfway successful, as it has the tendency to distract the reader from the story, causing one's thoughts to drift as easily as the narrator's. Shambles is, overall, an intriguing read, and Monroe has expertly crafted a quiet tale of outsiders coming together for both good and evil, and the emotional and physical aftermath of both types of confluences. – Melanie Haupt

Saturday, Oct. 30, 12:30-1:30pm, Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum Main Hall

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

How to Be Lost

by Amanda Eyre WardMacAdam/Cage, 290 pp., $24

Unlike this paper's esteemed Books editor, I am not acquainted with former Chronicle contributor Amanda Eyre Ward, so I have absolutely no qualms about singing the praises of How to Be Lost, Ward's second novel, to the heavens. I loved this book. I loved it so much that I read it in one day on the road from Washington, D.C., to Atlantic City, breaking only to play video poker. I love Ward's lean, elegant prose, which is subtly intimate, not painting the characters too broadly. I love how Ward chooses not to write her women as long-suffering martyrs, but as endearingly unsympathetic drunks with damaged souls but good intentions. How to Be Lost tells the story of a family devastated by a terrible loss, the mysterious disappearance of a 5-year-old girl, and how her mother and remaining sisters attempt to rewrite their lives around the space left by her absence. The narrative unfolds from the perspective of the oldest sister, Caroline, a former piano prodigy turned New Orleans cocktail waitress. She slowly reveals that her family was hideously fractured long before Ellie's disappearance; her abduction and presumed murder only served to deepen the schisms. Mysterious and hilarious letters from someone named Agnes Fowler pepper the narrative; the lonely librarian reaches out desperately, indiscriminately, in an attempt to fill in the blanks of her own hazy, poorly remembered past. The letters are charming, embarrassing, and thrillingly stilted, providing the comic relief for a wrenching story of loss, betrayal, and bone-crushing heartbreak. If it sounds cheesy or clichéd to say that as Caroline enacts the search for her missing sister, she finds the family she's been missing, take it as a testament to Ward's deft touch that the novel is anything but clichéd or cheesy and nothing less than a joy to read. – Melanie Haupt

Saturday, Oct. 30, 1-2pm, CE2.010

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

Magical Thinking

by Augusten BurroughsSt. Martin's, 268 pp., $23.95

While not the sole gay memoirist, Augusten Burroughs is the Chris Rock to David Sedaris' Jerry Seinfeld. Sedaris can Talk Pretty all day, but Burroughs (Running With Scissors, Dry) will describe his transsexual co-worker as "Diana Ross after a particularly bad round of chemo." There are more than enough of those caustic one-liners to keep you on your toes through some of the less dynamic passages of Magical Thinking. Some stories depict a youthful innocence seen through the jaded glasses of adulthood, others merely function as experiments in dysfunction and self-absorption. Between spurts of laughter there emerges an engaging and evolving character in Burroughs. From the man-hopping solipsist ("I am startlingly self-centered. I require hours alone each day to write about myself") to the happy co-habitator ("I have given up a certain degree of freedom. The ability to plow through my life with utter disregard for the thoughts and feelings of other people. I can no longer read a magazine and throw it on the floor"). But with story titles like "Cunnilingusville," "Ass Burger," and "Holy Blow Job," no one's taking themselves too seriously. The devilish humor is certainly in the details, but it's those same details that, by book's end, strongly characterize the author ... imperfections gladly included. Burroughs relates his good fortune: "Somehow, through a flip of the coin, I ended up here. Feeling like somebody at the top of the heart-lung transplant recipient list. Damaged but invigorated and fucking lucky." – James Renovitch

Saturday, Oct. 30, 1:45-2:45pm, Senate Chamber

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

The Covarrubias Circle: Nickolas Muray's Collection of Twentieth-Century Mexican Art

edited by Kurt HeinzelmanUniversity of Texas Press, 183 pp., $34.95

Hungarian-born photographer Nickolas Muray was a close friend of Miguel Covarrubias (1904-1957), the Mexican artist living in New York in the 1920s and Thirties when the city was a modernist mecca, and all things Mexican were in vogue. Covarrubias, whose distinctive caricatures and style appeared in print and on stage, socialized with other Mexican artists (Frida Kahlo, Rufino Tamayo, Juan Soriano, among others) working and thriving in New York during this extremely formative period, and Muray was there to witness the creative production of this period and support his friends by purchasing their work. His personal collection of 20th-century Mexican modernist art, now housed at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas, is featured in The Covarrubias Circle. While Covarrubias' work dominates the volume, other artists are also included. Six essays offer useful insight into this verdant period in Mexican art. Together with the color plates, the volume provides a fascinating portrait of the time and appreciation not only for Muray's foresight to collect these works but also for his contribution as a fine-arts photographer. – Belinda Acosta

Saturday, Oct. 30, 3-4pm, Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum Texas Spirit Theater

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

Queen of Dreams

by Chitra Banerjee DivakaruniDoubleday, 340 pp., $21.95

Rakhi is a painter and tea shop owner who has never been to India, yet paints an imagined India on her canvases and fetishizes her parents' experience of their native country, about which they are frustratingly mum. Rakhi feels "too American" and seeks out a more "authentic" Indian identity; what Divakaruni seems to be getting at in her sixth novel is that in this "variegated world" there is no such thing, although she cannot resist a sly, good-natured jab at the academics who try to categorize the hybridized postcolonial subject. Rakhi's mother is a dream interpreter, a gift that the daughter covets and that the mother guards jealously. For Rakhi, it is something uniquely Indian; for her mother, it is the defining factor in her own identity, her one true tie to her homeland, and she refuses to share it with her child or her husband. Once the mediating factor of the mother is gone, Rakhi and her father connect, and she finally gets the narrative of India she craves as her father rediscovers life outside the bottle. Food is the medium through which Rakhi unlocks her Indian identity; while Rakhi's mother is the Queen of Dreams, it is Rakhi's father (the King of Kormas?) and his tales of working in a Calcutta snack shop that allow her to connect with her heritage with unexpected, but enriching, results. While Divakaruni's novel is a delight, it also frustrates. Some of the narrative clunks a bit, namely the September 11 subplot, which feels painfully contrived and embarrassingly obvious despite its importance to Rakhi's development. Additionally, Divakaruni repeatedly makes overt what should have remained subtext; why would an author deny her readers the heavy lifting of interpretation, a courtesy she seems only too happy to extend to her characters? This technique undermines what is otherwise a thoroughly lovely and thought-provoking work. – Melanie Haupt

Sunday, Oct. 31, 12:30-1:15pm, Senate Chamber

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

S.E. Hinton's Hawkes Harbor is a book of firsts: Her first book since 1995's The Puppy Sister, written for the school-age youth audience. Her first novel since 1979's Taming the Star Runner. Her first book expressly for adult readers. Her first story with group sex, Burmese pirates, and the IRA.

Hawkes Harbor follows protagonist Jamie Sommers on a crash-bang voyage through his 1960s post-adolescence, with leaps in time and space that stretch the imagination: from a hard-luck orphanage to high-seas adventure with his friend Kellen Quinn, from a mental institution to drafty Hawkes Hall, a Delaware manor whose occupant has a generations-old secret. It's a dizzy whirl, a real potboiler with shark attacks, amnesia, rough sex, and gun running. In the middle, the story takes a hairpin turn away from Hinton's celebrated gritty realism and into the realm of fantasy. Yet the fantastic odds and ends cohere to form a cracked portrait of a broken man who struggles toward his own redemption.

Tired from her U.S. book tour and nursing a cold, Hinton talked about writing the book, which she'll present in a reading at the Texas Book Festival.

Austin Chronicle: Aside from the drugs and the sex and all that, how would you say Hawkes Harbor is different from the work you've done before?

S.E. Hinton: It involves adult characters. You know, I'm out of high school. I'm all over the world instead of in one place. It's just an adult book.

AC: Did you undertake the same kind of writing process?

SH: Of course, I've written every single one of them differently. This one I thought of in terms of scenes that I wanted: Jamie gets out of a mental hospital too soon, and Kell Quinn's background. I'd just pick a scene that I wanted to do that week, so I wrote them out of order. I actually wrote the last chapter first.

AC: I won't give away the surprise of the last chapter. Jamie is very much an "outsider" in the classic sense of your characterizations. He's a criminal, he's alienated from society, he's institutionalized for mental illness, and he has a secret of a more primal nature. Would you say that you are still drawn to outsiders?

SH: Oh, definitely. Yes. I find the dynamic of the character who isn't trained in relationships [and who is] trying to figure them out a really interesting thing to write.

AC: Why did you choose the 1960s setting?

SH: One reason was that I didn't want to deal with technology. I can barely deal with it in real life. I certainly can't write it. I didn't want satellites tracking Jamie and Kell as they went on their merry way. Another reason – I realize after I finished it – is that I was making some kind of metaphor for the Vietnam draftee with Jamie. He was yanked out of his own life and subjected to horrors and came back broken to the very thing that broke him and still held him in contempt. That was something I realized more after I'd finished the book than I did when I was writing it.

AC: None of the book's publicity materials mention the supernatural elements. In fact they came as a surprise to me as a reader. Would you describe Hawkes Harbor as fantasy fiction?

SH: Definitely. But the challenge for me was to keep it as realistic as possible while dealing with this element of horror and make it as much a part of everyday life as the other horrors that Jamie went through – I mention religious wars and battles for riches. To me it was [a question of] what people kill for. In the opening chapter Kell and Jamie are trying for a fortune. Later they try for God and country. It's almost a motif of man's search for God because Jamie doesn't believe, or doesn't want to believe. And then he gets captured, but he's serving this God-like thing [Grenville Hawkes, of Hawkes Hall] that needs praises and sacrifices and worship – the whole thing out of terror. And that turns out not to be God, either. God really turns out to be in the small things.

AC: Finding that out is the source of his redemption?

SH: Yes.

AC: For a while you weren't making public appearances at all. In addition to the Texas Book Festival, you've been all over the U.S. the last month. How does that feel?

SH: I'm tired. Really tired [laughs]. No, I never sought publicity for its own sake, and I don't like to go speak because I'm a private person. I like to stay home. But with the new book coming out, I felt like I needed to go and at least let people know it's an adult book. Don't buy it for your 12-year-old. But it is really exhausting. Besides the physical stuff, just mentally, it's exhausting for me to put myself out there.

AC: What's the reaction been like?

SH: Most of it's been very favorable. A couple of people were shocked. But I knew it wasn't going to be everybody's cup of tea.

AC: And controversy is something you've experienced before.

SH: Oh, yes. The Outsiders has been banned, and some of the others. But I didn't start out letting an audience dictate what I wrote, and I'm not going to start now.

Saturday, Oct. 30, 11:45am-12:30pm, House Chamber

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

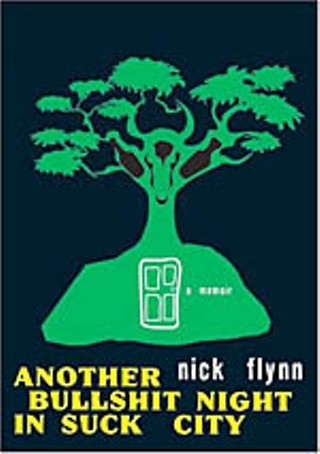

Nick Flynn is hesitant to call his new book, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, a memoir. "There's the risk of self-indulgence," the poet and University of Houston teacher explains from New York, "and the memoir seems like such a peculiarly American phenomenon." He says he settled on the term because "it seemed like I could write a million poems about [my father's homelessness] and it would always be assumed as a metaphor. It just felt like the only way to say, shorthand, 'Let's just assume this stuff is real.'"

The book focuses largely on Flynn's father, who left the family when the children were very young, was incarcerated in federal prison for check fraud, and eventually became homeless in Boston. Oddly enough, Flynn was working in Boston's most well-known shelter, the Pine Street Inn, while his father stayed there, but the two had little contact. Flynn was living on a houseboat in Boston Harbor at the time, having dropped out of college following his mother's suicide.

Flynn is, both in writing and in person, very careful to make clear that he does not think of himself as deserving of pity. He answers the allegation that his story is unique with a laugh and the simple response that "everybody I know struggles with their parents."

Unsurprisingly, Suck City does a brilliant job at forgoing the maudlin in favor of the absurd. He says his experience at the shelter reminded him of Beckett, characterized by "darkness, continually punctured by incredibly funny scenes, you know, hysterical absurdity and the weirdness of life and the comedy that's just inherent in every tragedy."

Flynn wanted his book to be a portrait of how one person became homeless, but he acknowledges that his father isn't the most sympathetic character. "I knew when I was writing the book that some people from the right could say, 'He's a fuck-up, he's an alcoholic, he left his family, why does he deserve anything from the government?'" Flynn says. "I don't know, I just think everyone deserves an apartment, whether they're a fuck-up or an alcoholic." He'd like his book to be a catalyst for dialogue with people who disagree, which is why he's excited to read at the Texas Book Festival, founded by Laura Bush.

Despite the memoir's success so far, Flynn still primarily considers himself a poet. "It's so perverse in this society to call yourself a poet," he says. "I love the glassy-eyed stares you get. It's such a perfect conversation-ender."

Sunday, Oct. 31, 11am-12:15pm, CE2.010 Read the full interview with Nick Flynn.

See www.texasbookfestival.org for full schedule.

Below is an extended transcript of the interview for "The Weirdness of Life: Nick Flynn on Another Bullshit Night in Suck City," a profile of the author in our Oct. 29 issue.

Austin Chronicle: You've dealt with some of your family's history in your poetry, specifically in Some Ether. How was the experience of writing the memoir different? Was it less or more emotionally exhausting?

Nick Flynn: There were a couple years of the writing, once I had gathered all the stories together, that felt like deeper psychological work. The first thing was doing research and putting things together, but then I had to try to figure out what it meant. It was really draining, psychically speaking. If I had a whole day, I would write for an hour and then be completely exhausted. I would actually fall asleep on the floor of my studio for 20 minutes to half an hour. I'd reach some sort of an impasse, a psychic impasse, where I just couldn't move forward in the writing. I would sleep and I would have a dream, and in the dream I would figure out where to go in the writing. Then I would wake up and start writing from that point. It was really this sort of accessing of the unconscious in some way. I would write for another hour and then I would fall asleep again, it would just keep happening. I'd do that maybe four times over one day. That part was an excavation.

AC: I wonder how it felt to be writing your father's life. In a sense, you had to animate him, think for him because you weren't there. I'm thinking specifically of a passage where you describe your father falling from the ladder. You write, "As he falls he thinks, If you are hurt they will come with their ambulances, they will put you in bed and feed you, they will let you rest." Then you step back and write, "Or maybe that's just what I have thought, the times I've fallen." It's a revealing moment, where you seem uncomfortable speaking for him, conscious of the fact that some of the narrative is conjecture.

NF: I'm glad I put that in there. As you were reading the beginning of that, I actually thought to myself, "Well, maybe that's just something I thought." That line was in and out of the book, so I'm happy I ended up keeping it. There were moments like that, where I was in his head, and I sort of wanted to tip my hand a little bit. I wouldn't think that anyone who read it would actually think I was in my father's head, but some people do wonder how I know certain things. I figure I'm allowed a certain amount of leeway just because he's my father, and the whole book is about the parallels in our lives. If I was writing about someone who wasn't so closely linked to me, it'd be a problem, and I think I would write it differently. It'd have much more of a speculative tone to it. I felt I was allowed certain things, because that's what the book was about, the son as a physical manifestation of the father.

AC: Now that the book is published, do you feel unburdened somehow, or do you feel more responsible to the people you write about?

NF: As far as the idea that "you write it and it sets you free" goes, I've never found that to be true. It doesn't hurt though. It moves you to see things differently. When a burden's lifted, another responsibility comes into place. Now I'm the one landlords call when my father's about to be evicted, which never happened before. At some point, I just realized that that was something I'd have to accept as the cost.

AC: A common thread in the criticism of all your work is your remarkable lack of self-pity, despite the weighty material. How do you manage to avoid coming across as being sorry for yourself, in view of the intensity of what you're writing about?

NF: The material is heavy, but the way I write hopefully has some air in it. It's not like this heavy loaf of something. Maybe on the surface there's some degree of extremity to it, but I just don't think it's outside the realm of people's imagination. Everyone I know struggles with their parents, and there are tragedies that arise in life. I never meant to write it as, "Reader beware, the tale I'm going to tell is a tale of woe" or something, because I really don't feel that way. I've worked with the homeless, I've worked with kids in the NYC public schools, I was out of the country for two years and spent a lot of time in Africa. ... The idea of self-pity as a white American living in the 20th century is pretty silly. As a straight, white, male American, I'd have to be pretty pitiful not to recognize the privileges that are inherent in being who I am. Earlier drafts of the book are dripping with self-righteousness, self-pity, and misdirected anger. I don't think you should edit that stuff out – you should write everything – but then you have to look it over and think, "Is that really the truth?" You realize that that isn't the truth, that the truth is more complicated. The closest you can get to it is to present what happened, and present it in a way with some sort of clarity. You have to let people come to their own opinions about it, or feel their own anger about it.

AC: You seem very concerned with truthfulness. Was it difficult to portray the homeless people you worked with, many of whom were mentally ill, in a way that was accurate and fair?

NF: Mental health is a continuum, and all of us have had days when we wake up further to one side than the other. If you're homeless, you end up getting stuck there [in mental illness], because all of your paranoias come true, neuroses are suddenly manifested into actual being, and it's just harder to swing back to the other side. That's one of the tragedies of homelessness, this sort of institutional codifying of homelessness and its causes, these people are homeless and "we" can't understand why. Not that I try to answer the question, but I try to get people to think about it, to realize that maybe it isn't so far outside the realm of understanding, how someone could end up here and the delicate things that keep people housed. That's why I wanted to show my father in his apartment also. It's a delicate negotiation to keep someone off the streets.

AC: At the same time, there's an undeniable humor to some of these people, often as a product of their mental illness. How did you acknowledge that humor without exploiting it?

NF: When I read this book in Boston – and I don't know if this is just an Irish thing – but people crack up, they think it's really funny. You read it in Minnesota and people weep, or they don't express any emotions whatsoever. I've been asking people lately to look inside themselves for whatever Irishness they have. To see that this is part of humanity, and there is a humor to it. When I worked in the shelter, it was like Beckett, and that's what makes Beckett so brilliant: this darkness that's continually punctured by incredibly funny scenes, hysterical absurdity, the weirdness of life, and the comedy that's just inherent in every tragedy. It's just the reality of it, you're out on the streets and you see ridiculous things. It is an absurd situation, and not to see that, to weigh it down with this tragedy, I don't see how that benefits anyone. There's humor throughout it, which just seems truer than something that's really ponderously heavy.

AC: Did you have to consider whether your book would "benefit" the homeless through its portrayal of them? You portray your father in a very honest, and sometimes unflattering, light. Did you have concerns about him being unsympathetic, in terms of the way readers might see him as determining his own fate rather than being a victim of circumstance?

NF: I'm reading at the Texas Book Festival, and I just found out that Laura Bush started that whole organization. Part of my book tour has been to try and infiltrate, so I try to put it in that perspective. I knew when I was writing the book that some people from the right could read this book, and could say, "Well, this guy deserves to be homeless. He's a fuck-up, he's an alcoholic, he left his family, why does he deserve anything from the government? Why does he deserve any help? This is what a safety net's for?" It always has to be like a mother with a kid, who's in a tragic situation, and we need to reach out and help her. I don't know, I just think everyone deserves an apartment, whether they're a fuck-up or an alcoholic. Why does being an alcoholic correspond to not having an apartment? Where did that logic come in? I think that's a very right-wing logic. If anyone's going to use that argument, I'd say, "Go ahead, use that argument, let's have discussion about it. If that's really what you think, you can take that logic to an extreme, and I'd like to do that with you, to see where you really would go with this."

AC: What do you hope the book accomplishes in terms of exposing people to the realities of homelessness?

NF: My father was invisibly homeless. If you saw him on the streets of Boston, you would never say, "That's a homeless guy." He just looks like a businessman, a retiree, a guy at a convention or something, just sitting reading the paper in the sun or something. Most of the homeless I dealt with weren't advertising their homelessness, because of the consequences involved. To admit that to themselves, or to society, would be a dangerous thing to do. That was really the point I wanted to get across: If you think that the situation is troublesome to you now, with this guy panhandling on the corner, just multiply that times 10, and that's the real number.

AC: What do you think is the difference in the emotional impact of the autobiographical poems in Some Ether and the memoir?

NF: One of the benefits of writing a memoir is that when you put the word "memoir" on it – even though I hated using that term, I wish I could just call it "nonfiction" – suddenly it becomes real, so that you don't have to convince someone that this is true. With the poems, about my father especially, it was really easy for people to assume, "Okay, this is just made up, it's just a metaphor. He's just taken this homeless person and grafted his father onto him. He's saying, 'That homeless person is like my father' and he's just taken out the 'like.' It felt important to point out that it was real. So that was definitely part of the impulse, because it seemed like I could write a million poems about it and it would always be assumed as a metaphor. For some reason, in people's minds, the words "father" and "homeless" in the same sentence, they couldn't contain it.

AC: Do you still consider yourself to be a poet, first and foremost?

NF: I do. I just love to because it's so perverse in this society to call yourself a poet. I love the glassy-eyed stares you get, it's such a perfect conversation-ender, unless someone is somehow connected to that world. Not to be off-putting, but I deeply love poetry. It's the thing that really deeply excites me, consistently. Not all poetry I read, of course, but a good poem is really something sublime to me.

AC: I don't imagine that you had an ulterior motive in writing this, but I wonder if you think that poetry is benefited when poets write prose. Do you think readers who discover poets through their prose will become more interested in poetry?

NF: People heard that the book was a little bit experimental, and they freaked out, like, "Oh fuck, I didn't want to buy something experimental!" You have to reassure them, "No, no, you can read this." I think it's a good thing to get people to read something that's a little beyond a straightforward chronological narrative. It shows them that there are different ways of expressing things, and that you shouldn't be intimidated by it. I like to think my book is actually an experimental page-turner. I wanted to have a tension to it that would make people continue reading, but it was important to have each section be the form it had to be, which wasn't necessarily straight narrative. So hopefully, people will read it and it will open them up more. Hopefully, they'll realize, "Oh, I don't have to be so afraid of all this other stuff."

AC: So you wanted it to be accessible, but not easy.

NF: Exactly. I deeply respect readers. I think they have so much capacity, which is why I didn't try to answer questions in the book. I tried to leave it open, because I really think that people have their own intelligence and that they'll come to their own conclusion. It feels more respectful to the reader to do that, not to treat them like idiots who can't handle something that's a little beyond their experience.