Triumph of the Yellow Kid

Comics are art, Spiegelman notes in his panel-busting history lesson

By Robert Faires, Fri., Oct. 22, 2004

From the beginning, comics knew the pain of the late Rodney Dangerfield: They didn't get no respect. When they started out in newspapers, they were "the funnies," little boxes full of gags, amusements, diversions not to be taken seriously. And the way they were drawn – simple lines, broad caricatures – made it easy for comics to be dismissed as crude, juvenile. The only reason they got color was because Joseph Pulitzer's plan to print polychromatic reproductions of real art – great paintings – in his newspapers was a washout. He had to use those expensive presses for something.

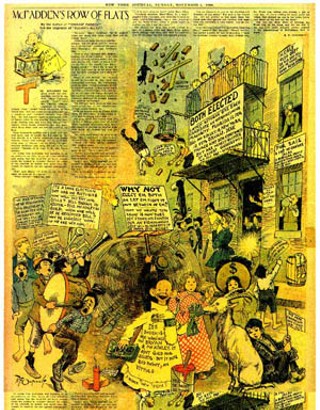

Never mind that the first comic to have color slapped on it became a sensation, that the anonymous street urchin in Hogan's Alley whose nightshirt was turned canary bright became a star, now and forever known as the Yellow Kid. Never mind that the public's response inflamed the circulation battle between Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, leading them into a financial tug-of-war for the strip and the services of its cartoonist, Richard Outcault. Never mind that artists were finding in comics new ways to tell stories and to comment on the culture – and that the public enthusiastically embraced them both. Comics were still, like that jug-eared punk in the saffron shirt, kid stuff.

And so it remained for almost a century.

Then, in 1992 Art Spiegelman was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for a book called Maus. The work was a rich, complex examination of the Holocaust and its aftermath, of surviving the Nazi death camps and being the child of a survivor, of family and identity and even artistic responsibility, but what was striking about it was that it communicated it all through comics. The story was told in panels of words and pictures. The characters were rendered as anthropomorphic animals, with Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. It was comics, but it was undeniably brilliant, and the culture seemed at long last willing to recognize the form's merit as art.

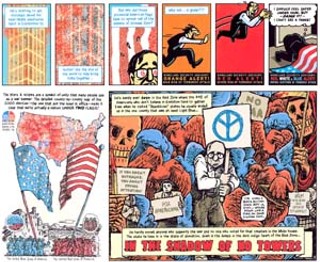

And now, a dozen years later, comics ... still don't get no respect. Oh, some room has been made for them in the Barnes & Noble, and more ink gets spilled about them than before, but respect? Not really. Not when an artist of Spiegelman's stature sets out to find a publishing home for his series of comics exploring life on and after 9/11 and gets the cold shoulder from the very arbiters of culture who had been quick to laud Maus and employ Spiegelman as an artist, that is, The New York Times, The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker. And while the just-published collection of these strips, In the Shadow of No Towers, has received some enthusiastic reviews (including one by the Chronicle's Wayne Alan Brenner: "Readings," Books, September 10, 2004), it's also earned its share of pans in which the critics sniff that it's no Maus.

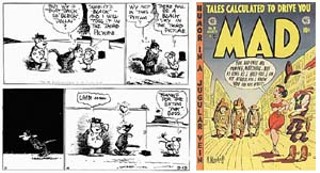

But, you know, so what? Like so many other art forms and genres – stand-up comedy, soap opera, crime fiction, Westerns, romance – comics have done just fine without respect. If you don't believe me, you can hear it from Spiegelman himself when he hits town next week to deliver "Comix 101" at Hogg Auditorium. This slide show/lecture, which Spiegelman has been touring around the country for some six years, offers a whirlwind history of comics in about 45 minutes, squeezing in everything from the satirical engravings of 18th-century Englishman William Hogarth and that eye-popping debut of the Yellow Kid to 20th-century newspaper strips familiar (Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy, Peanuts) and obscure (The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo), comic books, MAD, underground comix, and his own contributions to the form, including his seminal experimental magazine RAW and Maus. The current edition of "Comix 101" even features In the Shadow of No Towers.

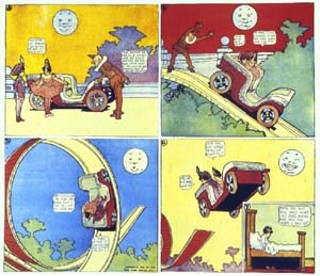

Spiegelman's point is that comics didn't start being art with a graphic novel about the Holocaust. They've been art all along. You can see it in Winsor McKay's Little Nemo in Slumberland, an elegant articulation of dream life, as freely imaginative as a bedtime reverie – with people flying or towering over cityscapes, inanimate objects springing to life – and yet rendered with such solidity and sweet style, you'd almost swear you were sleeping as you read it. You can see it in George Herriman's sublime Krazy Kat, which Spiegelman has noted could be read as anything from political allegory to psychosexual drama, but "the ineffable beauty of Krazy Kat was that it was simply about a Kat getting konked by a brick. It presented an open-ended metaphor that could contain all stories simultaneously."

In these and other early comics, the creators drew energy from the freedom they had to invent the form. There weren't rules yet to shackle their artistic impulses. Inevitably, time and the demands of commerce would bleed the form of its most adventurous elements, but every time that happened, a new form of comics would break through and shake things up again. When the roughness and anarchy of the early years were bled out, and the comics pages threatened to become nothing but tame domestic comedies, along came the adventure strips, with Harold Gray's Little Orphan Annie showing just how spunky and resourceful a girl can be and Hal Foster's Tarzan ruling the jungle with commanding power and grace, and Chester Gould's Dick Tracy coming down hard on the most violent and creepiest criminals the comics page had seen to date. The golden era of adventure comics – which expanded into comic books in the 1930s and gave birth to the superhero – faded following the end of World War II, but then along came the graphic horror comics of the 1950s, courtesy of EC Comics, and a new streak of anarchic, irreverent satire in Harvey Kurtzman's MAD. When MAD grew sedate, along came underground comix, with artists such as R. Crumb and Gilbert Shelton and Jaxon tapping the rebellious, experimental attitudes of the Sixties. And after those comix came above ground, Spiegelman launched the tabloid-size RAW, giving a dizzying array of wildly different comics artists a large scale on which to play with form and types of stories – even a tale of surviving German concentration camps with Jews portrayed as mice and Nazis as cats.

Today, comics in this country are flourishing, with more kinds of work being published and more attention being directed toward comics than at any time in their history. The vibrancy and diversity of the current scene can be seen just in the comics-related activity taking place in Austin over the next few weeks. Not only is Art Spiegelman coming to town to beat the drum for the whole form, but we'll be visited by comics legend Joe Kubert, an artist whose career has spanned seven decades and covered everything from Hawkman and Sgt. Rock to the personal graphic novels Fax From Sarajevo and Yossel, April 19, 1943; David Rees, the cartoonist behind the recent clip-art sensations Get Your War On and My New Fighting Technique Is Unstoppable; and, in a group, three leading lights of the independent/ alternative comics scene: Gary Panter (Jimbo in Purgatory), Seth (Clyde Fans, Palookaville), and Adrian Tomine (Scrapbook, Optic Nerve). As if that weren't enough, a museum is even getting into the act, with an exhibition of work by artists who produce or are influenced by comics ("Comic Release!: Negotiating Identity for a New Generation" at Arthouse).

So maybe some of the gatekeepers of cultural legitimacy still haven't granted comics their stamp of approval. There's too much stuff happening, too much exciting stuff being made, to worry about it. And it's clear that those little boxes with the words and pictures don't need it. As Spiegelman has said, "Comics have the power to fly under the critical radar and dive right into the brain. They get to the heart of what happens. They turn time into space. They're the power of still images in a world where everything is moving." ![]()

"Comic Release!: Negotiating Identity for a New Generation" is on display through Sunday, Oct. 24 at Arthouse at the Jones Center, 700 Congress. www.arthousetexas.org

Art Spiegelman

presents "Comix 101" on Thursday, Oct. 28, 8pm, at Hogg Auditorium on the UT campus. For more information, call 471-1444 or visit www.utpac.org.

David Rees

will read and show slides from Get Your War On II as part of the Texas Book Festival on Saturday, Oct. 30, 8pm, at Alamo Drafthouse Village, 2700 Anderson. www.texasbookfestival.org

Joe Kubert

will appear as part of the Jewish Book Fair on Wednesday, Nov. 10, 7:30pm at the Dell Jewish Community Center, 6500 Hart Lane.www.jcaaonline.org/bookfair

Gary Panter, Seth, and Adrian Tomine will appear in the panel discussion "Ray Guns and Moping," hosted by The New Yorker illustrations editor Owen Phillips, as part of The New Yorker College Tour on Friday, Nov. 12, 8pm, at La Zona Rosa, 612 W. Fourth. www.newyorkercollegetour.com