The Showdown at Lick Creek

As once clear water runs dark, a community defends its natural heart

By Amy Smith, Fri., July 2, 2004

If there is any good that has come out of the Lick Creek pollution disaster, it's that Warren Stinson successfully contested his property tax bill and got $10,000 knocked off the value of his modest homestead.

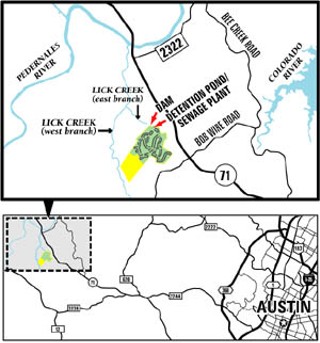

But Stinson's triumph (if one could call it that) over the county appraisal district is a very mixed blessing; it doesn't diminish the heartbreak and headache brought on by what caused his home's decline in value. About a mile upstream, at the headwaters of the east fork of Lick Creek, pollution discharging from a construction site storm-water detention pond and dam has turned the once pristine creek into a cloudy tributary that runs from brown to murky gray on any given day. It's been like that for almost a year.

There was a time, not long ago, when the lively creek and its sparkling swimming holes were among the best-kept secrets of western Travis Co. Now the word is out – not about the creek's charm, but about its sad demise.

Water from the west branch, as it flows past cypress-lined banks and steep canyon walls en route to the Pedernales River, still offers a clear view to the bottom of the creek bed. The creek's east fork, fouled and no longer translucent, tells a darker tale. According to the records of regulatory authorities, the now sediment-choked creek met with foul play from a troublesome pollution-control system put in place at West Cypress Hills, a master-planned community of what will eventually be 800 homes.

Since last summer, the project has been mired in controversy that grew more serious by the week and finally came to a crisis earlier this month. On June 18, the Lower Colorado River Authority ordered developer Russell Parker to shut down all West Cypress construction until the problem-plagued detention pond and dam are fully repaired and no longer polluting the creek. LCRA inspectors had discovered the complete failure of a filtration pipe in the detention pond. The vertical riser pipe is supposed to filter sediment from the pond but instead had collapsed during three days of rain the previous week, allowing more silt to sully the creek.

It was the second stop-work order issued in three months; an earlier notice applied only to the detention pond, while the June 18 order extended to the entire construction site – and will remain in place until the filtration system is functioning properly and a bypass pipe installed to redirect creek water around the storm-water detention pond.

Tom Hegemier, a water resources engineer with the LCRA, said he visited the site again on June 21 and saw immediate improvement. The pond banks had been hydromulched – a mixture of grass seed, water, and mulch that is sprayed over an area to hold soil from erosion – and a new riser pipe was ready to install. Hegemier allowed that frequent rainfall since January had created a near-constant pool of water in the pond, which delayed efforts to revegetate the area to prevent further soil erosion. Project engineer Ed Moore had hoped to finish repairs on the dam facilities by this week, and Hegemier said Tuesday that work on the riser pipe has apparently been completed. But continued rains have slowed progress on related reconstruction, and the stop-work order remains in place pending further repairs and LCRA inspection.

Residents were nonetheless amazed that several agencies would approve the placement of a detention pond, a dam, and a sewage treatment facility right on Lick Creek. Authorities confirm that creekside storm-control mechanisms are not uncommon but that this particular pond is larger than usual, covering roughly a four-to-five-acre area with a dam measuring 25 feet from top to bottom.

The pond's location, Hegemier said, "highlights a weakness in our [nonpoint-source pollution] ordinance. ... I would personally prefer to see buffer zones in creek areas." He said the ordinance is currently undergoing some stronger revisions that may address that issue, as well as the amount of pollution load that development projects are required to remove – currently 70%, compared to 100% under the city of Austin's Save Our Springs ordinance.

For a larger map click here

"If anyone had put a dam and a sewage plant on Barton Creek, they'd be in jail right now," observed Stinson, the Lick Creek property owner. He has a point. Within the regulatory confines of Austin, a project like West Cypress Hills would have received a thorough preliminary review and constant monitoring during construction. Beyond the city limits, property rights or the reflexive expectations of "economic development" often trump environmental concerns, or even ordinary precautions. As an example, Travis Co. Commissioners Court minutes from its March 9 meeting show that the preliminary plan for the project's first phase – 435 homes on 250 acres – passed unanimously, without discussion, as a consent item.

Catching Up

A Hill Country project like this one falls under the jurisdiction of multiple agencies, with each responsible for one aspect of the development. Even with this much theoretical "oversight" – or perhaps because of it – developer Parker managed to start construction without seeking legal clearance from all the proper authorities. He failed, for example, to obtain a permit from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers before building the dam – an approval required on all waterways like Lick Creek. Parker is now in the process of seeking the agency's approval – after the fact. "Most developers know they have to have certain permits," said Clay Church, a spokesman for the Corps' office in Fort Worth. "And any time you change the alluvial flow of an area, there's probably some regulatory agency that's going to require a permit."

Parker was also required to hire an environmental consultant, to determine whether the site is a habitat for the federally protected golden-cheeked warbler. That study is still pending. Normally, developers must secure clearance from the U.S. Fish & Wildlife well before any site clearing and construction work begins.

Additionally, inspectors from the county's Transportation and Natural Resources division, which oversees flood and drainage issues at the site, has issued five violation notices since December for problems relating to silt containment, according to TNR liaison Scheleen Walker. "That's a pretty typical violation at construction sites," she said, "but this is probably more than your typical number of violations issued."

Despite a series of project setbacks and an accumulation of bad press, Parker defends his project and says he's doing everything he can to repair the pond, including revegetating the pond area to prevent further soil erosion. "We don't just decide we want to build a dam and a detention pond," he said. "We're doing what's required of us." According to Parker, the subdivision's impervious cover makes up less than 15% of the project because 400 acres of the 1,000-acre plot will be preserved. "We're very proud of this development," he said. "It's a marvelous development with large buffers."

The project's engineer, Ed Moore, said that while the pond meets LCRA requirements for long-term pollution controls, an unusually rainy season contributed to the pond's failure. "There were just an unusual sequence of events," he said. Moore added that he and Parker had recently met with their investors to discuss the LCRA's stop-work order. "They told us to spare no expense to do everything we can to repair the problems," Moore said. "When you look at our low impervious cover, which allows for wide greenbelts between houses, this is really going to be an environmentally top-notch development."

Indeed, as the developers describe it, West Cypress Hills was designed to be a showcase project, one that would serve as a model for "rural by design" developments all across Central Texas. It is featured under that slogan on the Web site of one of the development's major investors, Castletop Capital, an Austin investment firm with large real estate interests. The firm's co-founder is Mort Topfer, the former vice chairman of Dell Computers, better known for his philanthropic contributions to the arts and other local endeavors than for big real estate deals in the Hill Country.

Outside Agitators – in Residence

For nearly 20 years, until the inception of the West Cypress project, Lick Creek had served as the lifeblood of the Stinson household, and Warren and his family had drawn fresh, clean water from the creek that meanders across his property. Not only did Stinson and his wife Jeannie raise three kids along the crystal creek, he put a pump in the waterway and supplied his family with spring-fed water the whole year round. The creek even provided the family's drinking water until some years ago when they switched to bottled water "for safety's sake." Seven or eight months ago, Stinson noticed that sediment from the creek water was mucking up the plumbing system and the hot water heater.

On three different occasions, he had to haul the hot water tank outside to empty the silt that had settled in the base of the tank. For Stinson, the polluted water represented the beginning of the end of a way of life. "I have never in the last 19 years had to filter this creek water," said Stinson, who runs a tree-trimming service and plays in a blues band on weekends. "Now I don't think there's a filtration system I would trust." He has since shifted to well water. "As far as I can see, the days of clear creek water are over," he said.

Thus far, Stinson is the only area resident to contest his property tax bill on the basis of the degradation of the creek. His neighbors and other residents say they had not considered following Stinson's course of action – until they learned of his reprieve from the county appraisal district. The outcome may not be as fortunate for them, however, because Stinson is the only Lick Creek resident who relied on the tributary for his home's water needs. In any case, the deadline for registering protests has come and gone for this year, but several homeowners said that if the creek is still degraded next year they might contemplate such action.

Lick Creek, they repeat, is the natural magnet to this corner of the Hill Country. Like Stinson, many other residents say they followed their dream of owning a piece of land that would leave plenty of open space between them and their nearest neighbors. One look at the creek and folks are smitten. "We're here absolutely, 100 percent, because of the creek," said Richard Streety, a retired real estate agent who settled on the waterway 18 years ago. "Everybody lives here for the same reason."

And by most accounts, the residents have always done their part to protect the creek. Pepper Morris and her neighbor, Janet Gilmore, serve as volunteer stream monitors for the LCRA, which is how Morris knew to contact the river authority at the first sign of the degradation that she first observed last August.

Morris and Gilmore also note the irony of how quickly the Lick Creek residents were labeled "activists" and "agitators" by pro-development forces – just for trying to protect their own property interests and a Hill Country creek. Those few who aren't fired up about the polluted creek are looked upon more favorably by their newest neighbors. Parker, the developer, insists there are "moderate" homeowners in the area who are more accepting of his development. Morris said she was particularly irritated by an opinion piece by County Commissioner Gerald Daugherty (whose precinct includes western Travis Co.) that was published in the Lake Travis View. The headline warned readers to "Face Facts: Growth Can't Be Stopped Altogether." Morris responded: "That's insulting. Nobody out here is that naive." (Daugherty declined to comment on Morris' reaction or on development issues in general in his precinct.)

"People move out here to relax and enjoy their lives," said Gilmore, who moved to the creek with her husband, singer/songwriter Jimmie Dale Gilmore, 10 years ago. "Nobody out here planned to become an activist. The creek is an issue that crosses political boundaries – they'd be doing the same thing if something like this happened in their back yard."

Community Self-Defense

By plan or default, one additional good thing about the Lick Creek disaster is that residents up and down the State Highway 71 corridor have begun to mobilize in the face of the officially prevailing laissez-faire attitude to development in unincorporated areas of the Hill Country. If nothing else, the recent heavy rains have served to remind the whole community that, as confirmed by the LCRA and other authorities, the Hill Country is one of the most flood-prone areas in the entire country.

Lick Creek property owners have organized themselves as Guardians of Lick Creek and retained environmental lawyers Stuart Henry and Phillip Poplin. On June 9, the group put the West Cypress Hills developer on notice that if state and federal agencies don't effectively move to enforce penalties against the development for alleged violations of the Clean Water Act, a lawsuit would be forthcoming. The Guardians expect to know their next legal move some time in August.

Poplin points out that all the agencies that signed off on the detention pond and dam share fault for what has transpired since Parker broke ground, but added, "The responsibility is squarely in [Parker's] lap." The cleanup of the creek presents an enormous challenge because so much destruction has already occurred, Poplin said. Even after restoration, if it ever reaches that point, the creek is still at risk of getting hammered, he added. "If you have that level of development upstream, there will always be a continuous dump of pollutants into the creek. I don't see how it can be prevented without some very, very innovative measures and responses." Right now the primary threat is soil erosion, as the creek fills with the topsoil runoff disturbed by construction and largely unimpeded by the attempts at detention. Down the line, the greater threats to the creek will be all the inevitable chemical byproducts of intensive residential development: oil, gas and other hydrocarbons, chemical and fertilizer runoff, miscellaneous waste, etc.

Residents say they were completely blindsided by Parker's initial development plans, and noted with some amusement that the required "public notice" for the project was published in the West Lake Picayune, a suburban community newspaper far removed from Lick Creek affairs. Neighbors saw construction trucks coming and going from the site, but the word was that the homes would be on deep, wide lots ranging from one to five acres. So life went on. But the actual plan – eventually to include 800 homes and at least twice that many vehicles – raised concern not just about the creek but about the already perilous Highway 71. (The project currently only has approval for Phase One, which includes 435 lots on 250 acres.)

"I don't begrudge him his right to make a profit," creek resident Jimmie Dale Gilmore said of Parker, "but when it impacts the creek the way it has, and it impacts the traffic to the extent that it becomes too dangerous for my kids and my grandkids to visit, then we might have to consider moving somewhere else." The problem is, Gilmore continued, "I don't want to leave. I'm just in love with that creek. It's a little treasure of Texas."

One of the biggest eye-openers for Lick Creek residents has been just how unresponsive the county and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality have been to demands for some sort of enforcement action – anything to stop more sediment from spilling into the creek. They say the county's violation notices for silt-containment failures are just that – notices, which carry no enforcement weight. While the county has little regulatory control on developments, TCEQ, on the other hand, carries the most weight on enforcement, but in this case spared the violator. The agency issued two violation notices against the developer in May, but last month "resolved" the matter without enforcement action, according to TCEQ records.

The agency currently scoring higher marks with residents is the LCRA, which has taken an active role in bringing the development into compliance with the agency's nonpoint-source pollution ordinance. Indeed, the agency is redoubling its outreach efforts after taking a beating over its plans to extend water service to three other proposed developments in the area, initially leaving other property owners in the dark about the plan, and potentially opening the door to more pollution-control disasters like West Cypress Hills. (West Cypress Hills is not currently seeking LCRA water and will rely on a well system for now – but the recent history of development in the area has featured increasing demand for additional sources of water.)

LCRA officials were taken aback by the loud public outcry against its water pipeline plan, and last month agreed to a seven-month moratorium on such water contract proposals to allow time for more public input and more forethought devoted to regional planning and water quality.

However, the LCRA board of directors recently did as the agency is obligated to do under state law, and approved a "raw water" contract for the proposed Lazy 9 development, also called Sweetwater Ranch or Davenport Ranch, in western Travis Co. The Lazy 9 developer did not want to wait out the duration of the moratorium, so the raw water contract deal allows the development to draw water directly from nearby Lake Travis. This week, Travis Co. commissioners approved the development's preliminary plan – but only after developer Bill Gunn agreed to comply with stricter (though yet-to-be specified) environmental rules on subsequent phases of the project. Commissioners, meanwhile, ordered staff to begin drafting tighter environmental controls that in theory would apply to new developments in unincorporated areas. Neighbors of the project expressed relief that the development would be subject to future regulatory safeguards but remain wary of the overall size of the project – 2,857 new houses on 2,260 acres – and its impact on area waterways. While the commissioners were making their peace with Gunn, the Save Our Springs Alliance filed suit against the developer (see Naked City, p.15).

Wisdom in Hindsight If litigation by the Guardians of Lick Creek against West Cypress is to be avoided, it appears that state or federal agencies will need to take enforcement matters into their own hands. Lick Creek is worth fighting for, residents say, to preserve the creek as well as its rich history. Not only is Lick Creek known for its previously pristine waters, the creek's limestone cliffs are home to the Levi Rockshelter, an ancient Paleo-Indian campsite that dates back tens of thousands of years, one of the state's oldest archeological treasures.

In light of that ancient history and the notorious fragility of the Hill Country landscape, the community was stunned by how quickly push came to shove along the creek. "Everybody out here is so considerate of other people," said Janet Gilmore. "That's why it was such a shock to find out what this development had done to the creek."

After the damage had been done, residents met with Parker and his associates. That was the first time they learned the actual extent of the development. "They were really proud of their plan and they acted like we should be excited about this design," Gilmore recalled of the meeting. "They smiled and talked about this in glowing terms and assured us that everything would be okay. Some of us just sat there in surprise and some of the residents were really angry." In hindsight, Gilmore says she now wishes she and her neighbors had thought to investigate the actual size and scope of the proposed development before ground was even broken. "At the time, we just didn't have the awareness, or the foresight, or the paranoia to be checking up on this," she said. "Now we know what we're supposed to do." ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.