Lives Less Ordinary

The Austin Film Society's Neorealism and Beyond: Italian cinema, 1948-1970

By Marrit Ingman, Fri., Jan. 16, 2004

Amid the rubble of World War II, a new cinema was born. Its heroes were an unlikely sort: elderly civil servants, prostitutes, children, war widows. Its stars were nonprofessionals: university professors, cabaret singers, steelworkers thrust before the camera. The plots were minimal, and the films were shot on the fly in the lowliest locations with natural lighting, the audio dubbed in afterward.

Humble though it seems, the Italian neorealist movement influenced the making of movies in Europe and across the globe for decades to come -- technologically, artistically, philosophically. Its watermark is perceptible in the films of New Wave France, of the former Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia, of directors working in the contemporary Middle East and Asia. Neorealism taught the world that the lives of everyday people are remarkable, even beautiful, and that their struggles against poverty, mistreatment, and despair are representative of the human condition.

The latest series from the Austin Film Society traces the growth of the Italian neorealist cinema and its legacy, from Vittorio de Sica's seminal The Bicycle Thief to the lush international co-productions of the 1960s and 1970s, including Fellini's Technicolor marvel Juliet of the Spirits and de Sica's prestigious The Garden of the Finzi-Continis. The series suggests that when production shifted away from the bombed-out streets of Roberto Rossellini's Roma and back to Cinecittô, the magnificent studio built by Mussolini and made famous by Ben-Hur and other epic big-ticket productions, Italian films retained the humanistic qualities typified by neorealism.

Some of the later films in the series are indeed quite grand, but their heroes are the same "little" people: office workers and machinists, ordinary men and women with flaws, bad luck, or an unfortunate relationship to history. They search for love, for work, for stability, for a better life, for contentment, for answers. The results are sometimes tragic, as in the conclusion to Michelangelo Antonioni's Il Grido. Other times they suggest a cockeyed optimism, as when a heartbroken Giulietta Masina flashes a wry smile at the end of Fellini's Nights of Cabiria. But they always feel true to life.

First in the series, Cabiria (1957) features Fellini's wife and muse in her greatest performance: as an unsinkable streetwalker whose heart gets in her trouble time and again. With her expressive face and broad body language, Masina is the antithesis of the typical neo-realist nonactor. (The scene in which she dances at the Picadilly nightclub -- after getting tangled up in the curtain that cordons off the exclusive clientele -- is classic physical comedy.) Yet the influence of neorealism is manifest in the story's episodic structure and in the way that Cabiria drifts from place to place with one heartfelt wish: "Help me change my life." We know her plans of retirement are pipe dreams. Her best hope is to stay out of the Tiber, where her dissembling suitors like to throw her. Moments of the film are cruel and hard to watch, depicting the dehumanization of modern life with the same zeal as its low tech neorealist predecessors.

Ermanno Olmi's Il Posto (1961) is similarly ambivalent about the fate of its hero, a young prospective office clerk from the Milanese suburb of Meda (Sandro Panseri). Olmi's camera loves Panseri, a nonactor with three screen credits; his slack, puppyish visage perfectly suggests a teenage innocent thrown into the maw of corporate-employment hell. As he submits to an absurd application process (an interviewer questions him about bedwetting and uncontrollable itching), Panseri befriends a fellow applicant (Loredana Detto), making a human connection in spite of the stultifying environment. Like Cabiria, Il Posto is good-natured and often comic, but the conclusion packs a whammy. The narrative is also loosely strung, with a documentarylike approach. Il Posto is little-seen (and sometimes known by a confusing alternate title, The Sound of Trumpets) but well worth a look; the screening, moreover, features a newly struck print.

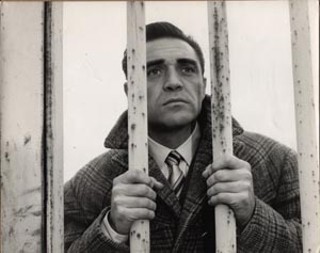

Next on the roster is Il Grido (1957), an early feature from cinematic adventurer Michelangelo Antonioni. Il Grido is a transitional film for the director. Its subject matter, its flatness of tone, and its location (among the working poor of the rural Po Valley) hearken back to the neorealist school and Antonioni's beginnings as a documentary filmmaker. It, too, is episodic in nature, following a mechanic (Steve Cochran) traveling aimlessly with his daughter in a fruitless attempt to leave behind the memory of his married ex-lover. There's almost no momentum to the story, yet the ending strikes a surprisingly effective note of doom. And in many ways, Il Grido prefigures the stylized, subjective-camera approach of Antonioni's later films, particularly international co-productions like Blow-Up and Zabriskie Point. Il Grido opens with a long traveling mise-en-scène shot of the desolate landscape, which symbolizes Cochran's bleak psychological horizons. Antonioni begins to use the camera not as a tool to record life objectively, but as a device to suggest meaning through the use of technique. Later he will concern himself more explicitly with how the act of constructing an image can distort and manipulate reality itself. It is also noteworthy that though the film's cast combines professional and nonprofessional actors (co-star Lyn Shaw, a British stripper, is credited only with this film), the acting style seems stiff and melodramatic, perhaps even purposely artificial, unlike that of the verisimilitudinous neorealist films.

Other notable entries in the series include a rare new print of Gillo Pontecorvo's Wide Blue Road, an obscure 1957 European co-production starring Yves Montand as a rural dynamite fisherman who is torn between securing a future for his family and helping the other locals, who are attempting to organize their labor.

Another rare print -- that of Roberto Rossellini's Stromboli -- screens on Feb. 17. Stromboli, of course, caused a sensation when it brought together superstar Ingrid Bergman and Rossellini. She was a fan of his neorealist masterpiece Open City, and mercurial producer Howard Hughes stepped onboard to back the production (and, eventually, to hack it down to 81 minutes for the American release).

The following week brings a screening of de Sica's The Bicycle Thief (1949), the quintessential "little story" about a poor man's search for the bicycle he needs to work. For its poetic simplicity and its deep and abiding humanism, the film has been properly lauded as the neorealist film.

Years later, de Sica reteamed with screenwriter Cesare Zavattini for The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1970), which appears at first sight to be everything The Bicycle Thief isn't: packed with superstar actors (including Dominique Sanda and Helmut Berger) and set among the leisure class in opulent late-Thirties Ferrara. The story, from the novel by Giorgio Bassani (though the script departs from it significantly), is as layered as The Bicycle Thief is fundamental, with flashbacks and trips back and forth across the Continent as Mussolini's "racial laws" build up to the outright removal of Italy's Jewish population from their homes and businesses. And de Sica pulls out all the stops, camerawise, with sweeping crane shots, rack focus effects, and everything but Vaseline on the lens -- anything to evoke the delicious, torpid, lush life inside the walls of the Finzi-Contini fortress. Yet the titular family, Jewish intellectuals who become increasingly unable to ignore the rising tide of Nazism, are treated with the same sympathy as the workmen and prostitutes of the neorealist heyday, for they, too, are powerless against the unfolding of history around them, against oppression, despite their apparent noblesse oblige. The film even ends with a shot through the too-quiet streets of Ferrara, similar to the opening of Il Grido. It's as desolate as the Po Valley, and a fitting close to the series on March 9. ![]()

The Austin Film Society's Neorealism and Beyond: Italian Cinema, 1948-1970 takes place Tuesday nights at 7pm from Jan. 13 through March 9 at the Alamo Drafthouse Village (2700 W. Anderson) except where noted.

Admission is free for AFS members with current membership cards or for new members signing up on the night of screening; $4 (cash only) for nonmembers. For more ticket information and updates, call 322-0145 or check out www.austinfilm.org.

Jan. 13: Nights of Cabiria

Jan. 20: Il Posto (new print)

Jan. 27: Il Grido

Feb. 3: Wide Blue Road (new print)

Feb. 10: TBA

Feb. 17: Stromboli (rare print)

Feb. 24: The Bicycle Thief

March 2: Juliet of the Spirits, Alamo Drafthouse Downtown (409 Colorado)

March 9: The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (new print), Alamo Drafthouse Downtown