Tale of a Tale Spinner

How a ballplayer, a piano player, beatnik poetry, and Lubbock shaped Terry Allen as an epic storyteller

By Robert Faires, Fri., Dec. 19, 2003

"I'll tell you a funny story about my mother," offers Terry Allen, grinning wryly like he does. "I was born in Kansas and moved almost immediately to Amarillo, where I lived the first two years of my life. And we lived in this house that my parents really liked. So when they sold the house and moved to Lubbock, they took the plans, and when they got enough money, they built this identical house in Lubbock. That's where I grew up, in this house. After my dad died, my mother sold the house -- by this time Jo Harvey and I had moved to California -- and she kind of moved around ... moved to California for a while, moved to other places. Then she ended up moving back to Amarillo, and she moved two blocks away from that original house, waiting for the woman in there to die so she could buy it back. She bought it back finally when the woman died. And we would go back to visit, and it was the identical house I grew up in, except it was 113 miles away in Amarillo. That was very bizarre. It was also totally typical stuff, that kind of displacement."

You want stories? Terry Allen has a million of 'em. Stories about his family, about West Texas and its extravagant characters, about displacement and alienation, about love and the open road. They spill off the dozen records that have won him his most ardent fans, like the story of "the Great Joe Bob," a high school gridiron hero who, his glory days faded, is reduced to robbing convenience stores; or of Jesus, God's Only Begotten Son, thumbing rides in West Texas and ultimately hijacking a car. They drip from the airwaves in his dramas for radio, from the tale of Bleeder, a Texas gambler, fanatic, mage, and hemophiliac, to the saga of the soldiers in Torso Hell, blown quite literally to pieces in Vietnam but resurrected by a "weird miracle." They overrun the multimedia works that have won him a Guggenheim Fellowship and three grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, like the stories of the eucalyptus trees that flow from hidden speakers in a grove on the University of California-San Diego campus.

Stories matter to Terry Allen. They're his heritage, a constant from his years growing up in Lubbock, the legacy from his relatives and a way that people there made a stand against the ever-present, ever-oppressive horizon encircling them and always threatening to flatten them out. And these tales of the things we do -- and don't do -- they've become Terry Allen's window into the human condition, why we are what we are, what it all means (if it means anything at all). In the four decades he's been drawing on them for his art, he has become a master of the form, a bard of West Texas, Homer of the Panhandle.

Right now the stories he's dealing with are very close to home. In fact, they are stories of his home. The sprawling work "Dugout," currently showing at the Austin Museum of Art, centers on his mother and father: who they were, how they came together, and what their shared life was like. He has used their stories to explore the worlds they came from, worlds largely lost to time now. Through them, he's opened a new window into himself and how he came to be this epic spinner of yarns.

Terry Allen wasn't supposed to be here.

By the time he made his appearance in Wichita, Kan., in 1943, his father was close to 60 years old and his mother pushing 40. Theirs was a romance that had blossomed late in life, and the last thing they expected out of it was a kid. Fletcher Manson "Sled" Allen was a baseball player who spent the early years of the 20th century touring the South in the bush leagues and playing pro for the St. Louis Browns. Later, he managed the Lubbock Hubbers baseball team and became a promoter of wrestling and boxing matches and musical shows. Pauline Pierce Allen was a professional piano player -- a real barrelhouse jazz and blues musician -- who had been booted out of Southern Methodist University in the 1920s for playing "devil's music" and playing it with blacks. The lives this pair had known had been full of smoky clubs, grassy fields, and miles of highways and country roads. What they both did for a living was play. How do you fit a kid into that?

Well, they tried. When ol' Sled created the Jamboree Hall nightclub out of an old church, Pauline and Terry were there. "She sold tickets," Allen recalls. "I sold setups when I was a little bitty kid, just walking around selling ice and lemons" to all the folks who had brought their own bottles since Lubbock was dry. His mother sometimes brought the boy along on her gigs. "One of her last professional jobs was in Santa Fe," he says. "When I was a kid, she played a couple of weekends a month at the La Fonda in the lounge. An early memory of mine is driving with her to Santa Fe and sleeping in the booth while she would play in the lounge. Get back in the car and drive back -- we always drove back."

Between his mother and his father, Allen was steeped in music. He heard her play, naturally, and she got him started on piano, teaching him "St. Louis Blues" (though after that, he was on his own, she told him). And at Jamboree Hall, he got a steady diet of blues and country: Friday nights the club booked only black acts, such as B.B. King and T-Bone Walker; Saturdays it was all country, acts such as Ernest Tubb and Hank Williams. ("Big-time segregated," Allen notes.)

But the music didn't sink in at first. That wouldn't come until the arrival of rock & roll, a sound that finally seemed to Allen to be about something other than the church or school or that flat line separating earth and sky. Until Carl Perkins issued the defiant command not to step on his blue suede shoes, life in 1950s Lubbock was a never-ending battle to keep from being overwhelmed by the horizon. "It's so stark out there," Allen says. "And it's awful hard to explain that to people who didn't grew up in that kind of experience, of what the horizon is doing to you all the time and what it does to your perception, in terms of something right in front of you and your eye goes through it to that edge."

So maybe, like young Terry, you drew. Or like the teenagers he hung out with, you fought or raced cars or you took about 20 cars to a cotton patch, parked them in a circle facing one another with every radio on the same station, and you all danced in the headlight beams. Or, like almost everybody on every porch in town, you told stories.

"My mother-in-law says -- and it's almost a cliché now -- 'America went to hell in a hand-basket when they got rid of the front porch.' And that's true," Allen laughs. "That's where culture was passed on. That's where women made quilts and gossiped, and that's where grandparents told their grandkids lies." He heard stories from his mother and father and the musicians and ballplayers who would occasionally drop by to relive old times. He heard stories from uncles sitting out back drinking beer, their tattoos providing stories all their own that young Terry would copy, drawing with his finger in the dirt "all these hula girls and panthers and knives and crosses and all that shit."

Tattoos were "a huge visual thing" in his world, a world that included only one piece of art in his entire house (an etching of a ship) and where the landscape provided no nourishment for the eye. "Lubbock and that part of the country was just so visually absent. You were so hungry to look at something," he says. So he took his art wherever he could get it, from the blue ink on his uncles' arms and the boxy panels in comic books and the warm illustrations of Norman Rockwell in The Saturday Evening Post. (Years later, when applying to Chouinard Art Institute, Allen was asked to name, in his view, the most significant artist in history; he named Rockwell, the only artist he really knew.)

At the time, of course, he had no thought of tattoos and comics as art. (Did anybody?) He no more felt their creative influence on him than he felt the influence of Hank Williams at Jamboree Hall or his father's story about having his tonsils burned out as a boy. (He was held down while a doctor stuck a hot poker in his mouth.) "I don't think I was really conscious of stories so much when we were listening to them," Allen admits. "You know how you hear certain things so many times in so many ways? When I heard stories about turn-of-the-century ballplayers, they were so alien that they made an impression. But I didn't sit around starving for stories. I think it was more just things that I absorbed."

He wasn't alone. If Monterey High School in Lubbock ever ditched the Plainsman as its mascot, it could do worse than replace him with the Storyteller. For out of that one institution at one time came Terry Allen, Jo Harvey Allen (then Koontz), Jo Carol Pierce, and Flatlanders Butch Hancock, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, and Joe Ely -- all artists with the gift for spinning tales. His classmates might have had a sense of that calling as teens, but not Terry. Oh, he felt a pull toward the creative -- he kept notebooks in which he'd write: "I want to be a writer. I want to be a musician. I want to be an artist." But he didn't really know that making art was an option for him. "I had that thing in high school of not having had a clue of what to do. Everybody I knew wanted to be something. I knew what I wanted in a sense, but it was so removed from any possibility," he says.

Then, when he least expected it, he got a nudge toward art. "It's funny, you think about those little permissions that you run into. When I was a sophomore in high school, the beatnik thing hit Lubbock, with coffee shops and people in leotards and berets and sunglasses and beatnik poetry. And I loved all that, whatever you could get your hands on, Kerouac and all that. I had an English teacher, and we were doing Shakespeare, and I remember writing a beatnik poem when we were supposed to be following her reading. She stopped the class and said, 'All right. Stand up and read that.' So I stood up and read this horrendous gibberish, fully expecting her to throw me out, and she just looked at me and said, 'You keep doing that.' I was stunned. And she was dead serious. 'You keep doing that.' That's the first -- maybe the only -- thing I can remember getting out of high school. It means so much to have somebody cross that line with you and give that to you."

After that, Terry Allen began to break free of the flat land.

He made it to California -- Jo Harvey now with him; they were wed in 1962 -- and started art school. And all those stories he absorbed all those years began to work on him. A friend in Los Angeles was living in an old house that had a working theatre in the basement, and with a few other pals, they created a play a week for a year: writing the music, building the sets, writing scripts. "None of us had any kind of theatre background," Allen admits. "But it was that desire to make something, to write a story. I didn't know that's what we were doing. We were just doing things to try to shock our peers. But that's what was really going on: We were learning the rudiments of how to tell a story."

And the basement theatre begat Rawhide and Roses, a radio show he and Jo Harvey cooked up for Pasadena station KPPC, an early FM underground rock station. Which begat Juarez, Allen's first record, a soundtrack to an imaginary movie about star-crossed couples blasting their way across the Southwest. Which begat Pedal Steal, the song cycle composed for the Margaret Jenkins Dance Company about a guitarist whose wild life ends in a motel room and an overdose. Which begat "Youth in Asia," Allen's sprawling consideration of American involvement in Vietnam. Which begat the "radio horror movie" Torso Hell, which begat the Depression-era hooker musical Chippy, co-created with all the Allens' Flatlander cronies. Which begat, which begat, which begat ...

And somewhere in all that begatting, Terry Allen was led back to the people who begat him. As he found himself around the ages his parents were when they met, he began to think about their lives and the stories they had told him. In 1993, he penned Dugout on commission from New American Radio, for which he had created Bleeder (1990) and Reunion: A Return to Juarez (1992). The title was a play -- better yet, a double play -- on words associated with his parents: a dugout being both the place in which his father sat at ball games and the hovel dug out of the earth in which his mother was born. The work's leading characters were, like "Sled" and Pauline, a ballplayer and a piano player, and Allen incorporated their stories, filling in the blank spaces in their tales.

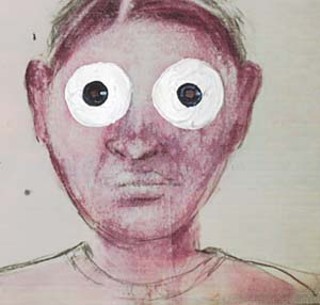

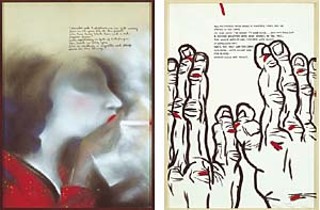

In the decade that followed, Allen began to expand his exploration of their world in visual terms. He produced dozens of drawings, in pastel, gouache, ink, and graphite, to illustrate their separate lives. The drawings from the ballplayer's story are rough, linear, like the blunt cartoons a high school boy might scrawl on his textbook cover during a tedious class. The drawings for the piano player's are soft pastels on darker paper with text in cursive. In displaying them, though, Allen links their stories: A panel of his is always paired with a panel of hers. The stories, as stuffed with incident as a novel, give the overall work that form's sweep and depth of character. We glean from the stories not just who these people are but how their paths will converge.

But Allen didn't stop there. He also created six "stages," three-dimensional installations to show their married life. In one, a coyote looped in fiery neon peers down from a wooden ledge extended over an image of crashing waves and two ballpark seats fastened together. Another has a chair with piano keys on the seat before a large image of a blue rose; to one side, the face of a blue-skinned sax player and to the other the face of a ballplayer, his red tongue sticking out with a pencil stuck through it. These works play off memory, using mementos and symbols to add strokes of mystery and melancholy. As if this still weren't enough, Allen allows us to hear the characters' stories read by Jo Harvey and himself over the museum's sound system. And Jan. 3-4, he will offer a "Dugout" theatre piece at the State Theater (see "Dugout III").

The epic scope of this work has everything to do with Allen's beginnings and his parents' world as he sees it now. "There was a bravery that both my folks had that meant a lot to me," he says. "My dad, I never heard him say you should do anything except what you want to do. He wanted to be a ballplayer, and that's what he was. He ran away from home to do it. Never was as good as he wished he was, but that's what his life was. When he got too old to do it, he made a new life for himself. He bought an old foursquare gospel church that had gone defunct and turned it into a nightclub. Then he started doing wrestling matches and boxing matches and sort of became the local promoter. My mother, she had some problems -- she was expelled from school for playing jazz, and you know, jazz was considered an abomination, and she was playing with black guys in Deep Ellum, so she started going to beauty school so she'd have a day job and worked the band at night -- but you think about the Twenties, for a woman to do that ... pretty nervy, especially when you think about the kind of opposition you'd run into. So I have a lot of respect for that, and I think back on those people, their friends, the stories they told, the same kind of breed of people. I was pretty lucky to be around them.

"The overriding thing about 'Dugout' to me is that it's another America, another time. It's the kind of people who deal with what they're dealt. Whatever kind of opposition they confront, they deal with it. Like the story of having the tonsils removed, which I always heard from my dad -- it's a true story. Now, the way I put it in the piece: the blizzard, the ladle, and all of that, that's all made up. But being held down and having his tonsils removed with a hot poker because he was gonna die and that's how they did it in rural areas -- that's a huge difference between [then and now]. Then, every little town was more than a little town. It was a world. Every farm was a world."

Those worlds gave Terry Allen a lot, and these days he is putting to use the storytelling artistry he acquired from them to keep their stories alive a little while longer. ![]()

"Dugout" is on display through Feb. 1 at the Austin Museum of Art, 823 Congress. On Thursday, Jan. 15, 7pm, AMOA Executive Director Dana Friis-Hansen will speak on "Terry Allen: Salvaging History" at the museum. On Thursday, Jan. 29, 7pm, Zachary Scott Theatre Center designer Michael Raiford responds to Allen's "stage sets" at the museum. For more information, call 472-9599 or visit www.amoa.org.

"Dugout III: Warboy (and the Backboard Blues)"

Terry Allen busts out of the museum with this theatrical component of "Dugout," co-produced with the State Theater Company. The new solo play, written and directed by Terry Allen, features Jo Harvey Allen telling tales of a man and a woman dealing with the unexpected arrival of their "Kid" (the Warboy of the title), along with live music by the author and Panhandle Mystery Band regulars Richard Bowden and Lloyd Maines. Two performances only: Saturday, Jan. 3, and Sunday, Jan. 4, 8pm, at the State Theater, 719 Congress. For more information, call 469-SHOW.