Hothouse Wildflowers

Through the looking glass with Eisley

By Melanie Haupt, Fri., July 11, 2003

Imagine a place not far from here, where young girls are free to shape themselves in a pure, unpolluted environment. A fantasy land populated with talking trees and golden rain, and where "golden rain" doesn't invite euphemistic snickers. A sphere inhabited by a fanciful group of sisters brought up apart from the vile outside world.

This is a habitat where adults nurture their offspring's creative impulses, allowing children to fully inhabit their imaginations free from the social pressures of growing up in the public school system. Here, blossoming adults are at liberty to hide in their rooms and read and write and draw and listen to music, not having to worry about wearing the right clothes, attracting the right boys, finding a date to prom.

To get to this destination, one must head to the culturally forsaken land of northeast Texas. It's unremarkable landscape, peppered with the odd farm and tiny high schools serving consolidated communities. The rolling hills, lush with wildflowers and regal, gently swaying trees, are a blank slate, acting as lovely, serene wallpaper for the rabbit hole transporting travelers from a vibrant urban center to a sleepy retail rodeo just east of Dallas. Here, the Olive Garden is fine dining and cholesterol is not so much an enemy as it is a condiment.

But you are not there yet.

Further out in the country, neighboring a car dealership, sits an abandoned, crumbling house being devoured by East Texas flora gone wild. At one time, this house, with its debris-strewn front porch and sagging roof, might have been loved, worth putting some time and effort into. Now, it's nothing but an eyesore.

Inside, beyond the filthy walls and peeling paint, past the insects and vermin, secrets dwell. These rooms were the greenhouse in which the DuPree girls -- Chauntelle, 21; Sherri, 19; and Stacy, 14 -- nurtured the lush dreamland for which they're quickly becoming known, along with their brother Weston, 17, and friend Jonathan Wilson, 19, as Eisley.

"The genesis [of Eisley] was their bedrooms," says patriarch Boyd DuPree, who has long since moved his family closer to downtown Tyler. "Their music is a product of their own culture."

Yet this culture, which has launched Eisley onto the world's stage, was contingent upon their being apart from the evils of reality.

Escape from the concrete jungles of greater "civilization" is exactly what brought Kim and Boyd DuPree to this dump of a house on the outskirts of the rose capital of the world, a move that's facilitated the collective musical careers of four of their six children.

"I Don't Think I Could Write Songs in L.A."

The leather-bound artist's book is still fresh, only a quarter or so of its pages bearing ink. Nevertheless, it's obvious that Sherri DuPree, who seems to have more pepper in her sugar 'n' spice allotment than her sisters, has already logged many hours in this book with a ballpoint pen. The drawings reflect a heavy surrealist influence, reminiscent of Magritte, although none of the kids has heard of him.

Populating the pages are numerous faceless girls in intricately detailed dresses, an anthropomorphized owl wearing a waistcoat and monocle, and a fowl-type creature with a teakettle for a head. Like Magritte's work, the simplicity of the images is misleading; the heavy lifting of interpretation is left to the viewer. Take, for instance, the faceless girls. Why no faces? It's Stacy DuPree who answers.

"Adding a face changes it too much," she offers. "It should be open."

Ambiguity in simplicity: already an Eisley theme that extends beyond the pages of a young woman's sketchbook.

"Sherri's drawings represent our lyrics," explains Chauntelle.

"I don't think I could write songs in L.A.," muses Sherri. "I need my nature."

Indeed, Sherri and Stacy's lyrics are Romanticism at its finest, minus the decadence and misogyny. Some might wonder why labels like Warner Bros. were wetting themselves to sign a band featuring the dreamy songwriting of a child who tells stories about people made of gumdrops and weeds. But like the faceless girls in the sketchbook, there's something about the music and its creators that's oddly alluring and contradictory at the same time.

Little girls should wear pretty dresses with matching bows, and their faces should be graced with sweet, innocent smiles. Little girls without faces hide something from the world, at the same time allowing society to project its own expectations on them.

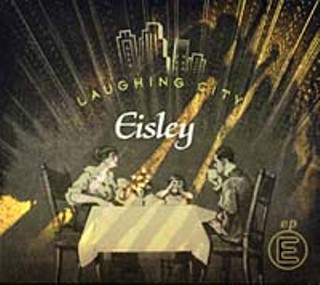

Laughing City, the band's debut EP, transports the listener to the DuPrees' world, if only for 19 minutes (read the Chronicle's review). The girls lift the veil, take you through their dreams, their nightmares, and into a world where the freakish Frankenzoo grazes and faceless girls peer inquisitively from among the wildlife.

There's the interlocutor's dread in "Telescope Eyes" as you face the menacing enemy, who bares its metal teeth and glares glassily from elongated orbs. When Stacy sings, "With light bulbs in our pockets, we'll light this darkened forest," in "Over the Mountains," you're thrust into a bluish nighttime canopy of trees that loom sinisterly while the sisters beckon, entreating you to join them as they plunge into the deepest depths of woodland.

Harmonized coos fill the spaces between the leaves, aural moss more meaningful than language. Before you know it, daylight breaks and Sherri swings higher and higher above the "Tree Tops," accompanied by tinkling music-box keyboards. You imagine in awe as she sprouts wings and soars ecstatically above the forest, drinking in the sun-tinged rain that falls and blesses everything below.

This is where Eisley transports listeners, and it's such an ethereal, absorbing journey that you expect it to just fall out of the air, not subject to the rigors that turn imagination into a commodity. The sad truth is, however, that the music industry and the DuPrees' flights of fancy are dependent upon one another in order to sustain the phenomenon.

If Dave Holmes, who manages Coldplay, hadn't spotted the band last November at the North Texas New Music Festival and set up a series of label showcases for the band in Los Angeles, the DuPrees might still be on the local club and festival circuit. Or, worse yet, forced to don a vest of Wal-Mart blue, closing the curtain to the glimmering grove in the face of hungry necessity. The kids take the whirlwind in stride, nonchalant but not disingenuous.

"It's not overwhelming, in a strange way," says Chauntelle. "It just seems natural."

Wes pauses his incessant wisecracking.

"We never really thought, 'Yeah, let's be a band so we can go on tour with Coldplay,'" he interjects. "It's just what we were doing, and that's just what happened."

"First-Graders Don't Do Drugs, but Third-Graders Do"

Chauntelle DuPree is the picture of maturing girlhood; her porcelain skin is smooth and clear, her eyes still kind, and her smile genuine. She's unaffectedly lovely, confident and self-assured, seemingly free of the awkward gracelessness of people her age.

It's hard to take your eyes off her, whether she's talking animatedly over a cup of watery coffee about the woeful lack of Starbucks on the road or folded comfortably into a shabby couch, her brand-new turquoise runners finishing off the long angles of her bent legs.

When she was 8, dyslexic Chauntelle struggled to get the help she needed at school, and her teachers were unsympathetic to her desire to color and draw. The Houston schoolhouse also revealed itself to be a hostile environment for nurturing tender young lives.

"When she came home and said, 'First-graders don't do drugs, but third-graders do,' that was the moment we knew we wanted something else for our children," recalls her father.

The young parents decided then and there that if the public school system couldn't support the kinds of morals and values they aimed to instill in their family, they'd educate the kids themselves. So, off to Tyler they went, driven by the hope that they could create the kind of life they wanted.

Things were shaky at first, the family living in a house that lacked the creature comforts of modern living like working indoor plumbing. The six children (the two younger siblings are Christie, 13, and Collin, 8) became a self-contained social, educational, spiritual, and creative unit. Eventually, perhaps even inevitably, Chauntelle and Sherri formed a band with a friend. And despite their claims to the contrary, sibling rivalry reared its ugly head.

"We weren't around peer pressure or competition like other kids," says Sherri, snapping her gum. "We didn't really grow up knowing about that stuff."

Chauntelle concurs.

"We weren't jealous of each other because we weren't allowed to be," she adds.

But while they didn't have a name for it six years ago, that's what sat with Stacy, then 8, outside her older sisters' bedroom door, longing to be a part of what was happening on the other side.

"I'd sit there and listen," says Stacy. "I'd always knock on the door, and they were always way too cool for me."

"You were little!" squeals Sherri indignantly.

"She would bang on the door, crying, saying, 'Let me in!'" insists Chauntelle.

Stacy is unruffled as she continues her tale.

"So, I just got a guitar and wrote a song."

That song was the first song adopted by the sibling band. It also ensured that Stacy would never be shut out of her sisters' room again.

"The Band's an Extension of the Worship Team Here at Church"

Not too long after the family relocated to Tyler, a new church cropped up in town called the Vineyard, a nondenominational religious organization that looks first to the Bible and secondly to music for its spiritual inspiration.

Catering to those who might not necessarily fit into the traditional church environment, the Vineyard plays weekly host to pierced Gen-X types with Manic Panic-hued hair who just want to worship without being judged. It's here that the DuPree posse, who like the Vineyard's constituency don't really fit into the mainstream, first aired their musical abilities.

"Basically, the band's an extension of the worship team here at church," explains Boyd. "Chauntelle started playing the guitar in church when she was 15; I play the drums."

Located in a strip mall not far from the center of town, the Vineyard is fairly nondescript. The sanctuary consists of a stage with a full band setup and not a pulpit in sight. The seating mingles couches with folding chairs, and a few tall, treelike plants strung with fairy lights complete the no-frills worship space.

Just outside the sanctuary is a lounge of sorts, stuffed full of secondhand couches, rickety card tables, and decorated with sundry coffee-related artifacts. Now just a gathering place for churchgoers before and after services, this was once BrewTones Coffee Galaxy, the coffee shop-cum-live music venue Boyd and Kim launched in 1998 in an effort to start an indie music scene in the decidedly hip-challenged East Texas burg.

First on the bill? The Towheads, three little blond sisters with familial support. From there, the kids started branching out beyond their hometown, playing clubs in Dallas' Deep Ellum district. It's a far cry from where they are now, milling about the erstwhile coffee shop while their father fusses over the jumble of videos on the table. Boyd tries to find just the right show from Eisley's recent 16-date tour supporting Coldplay to share with his visitors.

Grandaddy's latest album, Sumday, plays in the background. One of the girls starts humming along, then another, then Boyd and Weston join in, all of them falling easily into harmony with one another. It's as natural an act as scratching your nose, this family sing-along, but for this particular family, it's the reason that Boyd recently walked away from a partnership in a local graphic-design firm to tour.

Kim DuPree, on the other hand, stays home for the most part with the two youngest children and Chauntelle's 3-year-old daughter, whom Boyd describes as "another sibling."

"We Go to Cheddar's When We Want to Eat Nice"

Anyone who's spent any time with siblings might be surprised at the dynamic among this particular group. There's no bickering, no pouting, no hairy eyeballs cast across the room at a mortal enemy masquerading as a sister.

The feel among this group, including Boyd and Jonathan, is that of intimate friends -- the kind of friends who'd lay down in traffic for one another. What's it like when they're not on their best behavior?

"On the road, we hardly argued at all," claims Chauntelle. "We argued a lot more when we --"

"Weston and I were really bad when we were little!" interrupts Sherri.

This isn't the first or the last time the kids jostle each other for position in conversation, with the notable exception of Stacy, who sits quietly on the couch, staring at the floor, hands clasped between her knees, only interjecting a thought a handful of times.

Whereas most people react negatively to being constantly interrupted and spoken over, it goes unnoticed among the DuPree siblings, or if they do notice, the offended party simply listens and laughs. At this point, Wes points out that interpersonal irritants among the family band are often situational in nature, rather than stemming from wholesale clashes in personality or ideology. It's hard to imagine what these children could do to piss off one another.

After spending the bulk of their youth under Texas' sheltering sky, now the kids just want to spread the love. In fact, their only grouse about everything that's happened to them so far is that they were too rushed on tour; schedules often precluded the band from meeting their fans after each set.

"To me, being in a band is about more than just playing our music and leaving," says Chauntelle. "It's also about reaching out to our fans, making connections with them, building relationships."

Suddenly it's clear that the blank faces in the drawings hide nothing; rather, they signal an open love ready to be shared, to take its own forms once released into the world. And when you emerge from the other side of Eisley's enchanted curtain, you may be hungry. Your hosts are quick to offer suggestions.

"We go to Cheddar's when we want to eat nice," says Chauntelle.

You thank her and say goodbye. Later, heading back through the looking glass to the harsh realities of the world, your stomach full of high-class Cheddar's chicken fingers, maybe, just maybe, if you look closely enough, you'll see a few eyeless faces peering out from the trees, beckoning you to come and play. ![]()