Pure Happiness

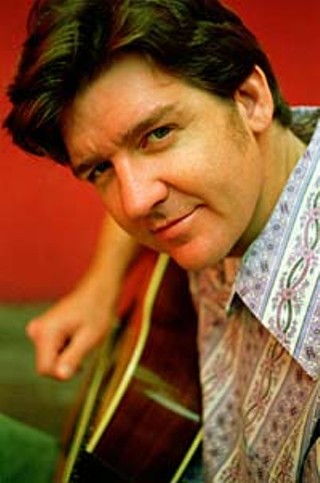

Austin's Bruce Robison, the unwitting toast of Nashville

By Andy Langer, Fri., Sept. 28, 2001

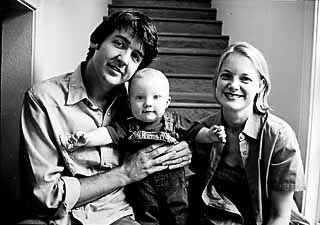

Last June, a prank phone call was the last thing either Bruce Robison or Kelly Willis needed. In fact, when they saw the blinking light on their answering machine, they'd just arrived home from a two-day hospital stay necessitated by complications with Willis' pregnancy. The message from Robison's Nashville publisher, Frank Lidell, began with an order: "Bruce Robison ... go get your 12-pack, stop this message, and come back to listen to the rest of it." Too emotionally spent to heed the instructions, they listened straight through. Then they listened again. And then another four times.

"The message said Tim McGraw had cut 'Angry All the Time' earlier that day," relays Robison. "We kept listening to it, and I kept telling Kelly, 'He knows this wouldn't be a funny joke right now, doesn't he? He wouldn't screw with us, would he?'"

If you've listened to country radio in the past two months, you know it was no joke. McGraw's duet with wife Faith Hill is currently No. 7 on Billboard's country singles chart. It's the kind of hit that will both finance young Derel Otis Robison's baby formula and his college education, too. Even so, Robison's still a bit incredulous.

"It's not something I ever imagined or planned," he says. "I honestly never imagined anyone with the commercial potential of Tim and Faith cutting one of my songs. It wasn't in my business plan."

Indeed, Robison's business plan was far more straightforward. Originally, it was that he'd pay his bills making albums and playing shows, spending whatever time was left concentrating on pitching his songs to other artists. Eventually, he came to believe he might be able to build a modest retirement nest egg through having songs cut by both friends and family: his wife, brother Charlie Robison, Monte Warden, perhaps even one day the Dixie Chicks. And while landing a track on Lee Ann Womack's multiplatinum I Hope You Dance was both encouraging and profitable, Robison knew it was a long leap between providing album filler and a commercially viable single.

"In my hearts of hearts I wasn't counting on anything like this," he says. "I'm a very pragmatic guy. My family, down deep, we're all tradesmen. My dad went to college, but he was the first. The Robisons worked in sheet metal and electrician trade unions, so it still colors my outlook on life. It doesn't color Charlie's. He looks at what's happening to me and says, 'Yeah, hell yeah, that's a great song. No wonder they cut it. It's about time.' And I'm like, 'Can you believe Tim McGraw and Faith Hill cut that song? It's just nuts.'"

Charlie Robison's not far off the mark: When you get to the story behind the hit and its writer, it's not that nuts at all. It's payback. For more than a decade, Bruce Robison has knocked on doors and endured rejection up and down Music Row. More often than not, they sent him packing with a backhanded compliment -- his songs were too "smart" for radio. Through persistence, the quality of his Rolodex wound up translating into small victories.

One of them was a deal with Sony Nashville's artist-friendly Lucky Dog imprint. Robison saw making albums as a way to increase his profile in songwriting circles, and it did. Despite a lack of radio interest, Sony funded a video for the first single from Robison's 1998 album, Wrapped. The "Angry All the Time" video may have only aired a few times on CMT, but it was enough to catch Faith Hill's eye. Two years later, she put it on a short list of songs she was considering for her next album.

Hill's husband Tim McGraw later told Robison he heard the song and "stole it right off her list." Now, Hill's considering another Robison song, while Womack is also reportedly going back for seconds. And there's no better indicator that Robison is Music Row's new Golden Boy than the fact that Garth Brooks just cut Robison's "She Don't Care About Me." Word might come as early as next week as to whether the song made the final cut.

"As lucky as I feel, I won't argue that I've done the work," Robison says. "I'm proud to have driven my ramshackle Mustang there and back for 13 or 14 years. Now I know why I did it. All the stuff I've done adds up step by step, six degrees of separation at a time. And now it really does feel like it's true that if you stay in there swinging long enough, you might get a single or double every once in a while."

Walking Away

Lately, Bruce Robison has spent an inordinate amount of time licking stamps. Such is the life of an independent artist; as CEO of his own Boar's Nest Records, order fulfillment falls to Robison. And yet, he's not filling orders for his new CD out of necessity. Country Sunshine could have easily borne Sony's imprint.

Despite very modest sales of 1998's Wrapped and '99's Long Way Home From Anywhere, Sony gave the green light for a third LP. But after a round of meetings with the label last year, Robison thanked them for their patience and moved on. Artists saying they didn't exercise their option when they were actually dropped is commonplace, but Robison truly walked away.

"In all honesty, if they'd have said this is the one where they bust it all open and put the full resources of Sony Music behind me, I'd have probably stayed," he admits. "But I went in to talk about what they wanted to do with this record, and there were blank stares. It was like, 'What do you mean? We're going to go sell Joe Diffie records. We're really happy that you found a home here. You deserve a place to make records, and this music deserves to be made.' They felt like they were doing me a favor and in many ways they were."

While not being pressured to sell CDs sounds like a luxury, Robison says the further he got into his deal without selling albums, the more he realized his career needed to be about the long haul rather than a quick cash-in. The long haul meant selling songs to other artists, only cutting songs for Sony meant handing over the rights to the masters and songs themselves. Even though Sony seemed more content releasing his albums than promoting them, Robison says it didn't stop him from trying to deliver the kind of songs Sony could land on radio.

"I'm not going to say I didn't have enough artistic freedom, I could do whatever I wanted there," Robison says. "But I think that's a complicated thing. I believe if you're going to be on a major label you should think about country radio, or you may as well not be there. Radio is their forte. And as far as grassroots marketing to avenues outside the mainstream, they're just finding their way."

In hindsight, Robison admits his effort to write and record with radio in mind may have diluted the quality of Long Way Home From Anywhere, saying now, "It felt a little forced." Country Sunshine is exactly the opposite, notably more genuine and free-flowing. Ironically, now that he's separated himself from the major-label machinery, he's made the most radio-friendly album of his career. Sunshine is just pop enough for AAA and just country enough for country radio. Not only do the drums and overall production sparkle, but there's nary a dull or uninteresting narrative.

Better yet, three of its songs have already been cut by other artists. Womack recently laid claim to "Blame It on Me," while Allison Moorer cut "Can't Get There From Here," which she co-wrote with Robison. Next month, Gary Allen will release his version of "What Would Willie Do," Country Sunshine's centerpiece and Robison's live show-stopper. As humble and self-effacing as Robison can be, he's clearly very proud of Country Sunshine.

"As time goes by, I figure out more ways to record songs the way I think they should sound," explains Robison. "The studio is a weird thing. You spend so little time there compared to everywhere else, yet there's so much pressure to get it right. And as a young artist, you just don't have enough information to manipulate all the elements, especially if what you want to do isn't the state of the art at the moment. You record in Nashville right now, and the drummers are slamming away on things like it's an Eighties rock record. That's just not where I come from.

"Kelly's last album was a big inspiration for me," he continues. "I'd always liked her records, but [What I Deserve] is more her than any of the others. It's more like the way I see her and the way I hear her sing. I wanted to get closer to that. And I think it's the closest I've come to getting the songs to sound like when I wrote them or how I hear them in my head."

Family Affair

At a gig in Dallas last week, a fan approached Robison to sign her CD. "I'm glad you didn't wear that blue shirt with the brown polka dots again," she told him.

Robison says it's a particularly telling anecdote of why he considers himself a songwriter first and a performer second.

"I only have about five shirts I wear onstage," he quips. "I'm inept at trying to look like somebody important. People tell me all the time that if I just changed the way I dressed, or did this or that to my hair I might look like somebody. But I've always felt like I didn't have any real aspirations to that end. I've known for years I'm not going to make my living from the back lounge of a tour bus parked outside an arena. I grew up on Ronnie James Dio playing arenas. That's not the kind of guy I see in the mirror."

Although Sony's interest raised his hopes that he might carve out a career as a performer, for the better part of a decade Robison has seen a songwriter staring back at him. If brother Charlie carried himself like a country star before he sold any albums, Bruce Robison carried himself like a songwriter before selling any songs.

"Once I started writing songs, it felt right to me," he says. "It was the first thing I knew I could be good at. It wasn't like basketball or school. Songwriting was an open door. So even if I wasn't making any money at it, I called myself a songwriter. I may have been peeling potatoes in the same kitchen for a living, but I knew this was something I could be good at."

Even so, how is it that a songwriter that spent so long trying to break into Nashville was willing to walk away from a deal with Sony Music? Robison says his decision to pursue songwriting over performing was influenced in large part by his family. Ten years ago, he had a courtside seat for his future wife's struggles at MCA.

"I saw what it was like to be a square peg in a round hole," he says. More recently, he watched Willis sell more than 100,000 albums with virtually no radio play outside Austin. From Charlie's deal with Sony, he learned what it looked like when a major label pledged serious support. And from Charlie's wife, Dixie Chick Emily Robison, he saw not just the amount of work that goes into maintaining stardom, but that a song like "Wide Open Spaces" could find a home at radio.

"You look at my family and it's easy to see the possibilities," Robison says. "Seeing people around you work hard and succeed is inspiring. It beats eating breakfast tacos at 4pm, although that's a lot of fun, too."

If there's a downside to Robison's intense focus, it's that he's built his career to the point where he rarely has time to write. With an album to support, a label to run, a catalog to pitch, and most importantly a new son, Robison says getting into a writer's mindset has been increasingly difficult.

"When I first started writing songs, I had that Austin kind of free time, where you watched so much TV you couldn't watch anymore," he recalls. "It's like, 'I might as well write a song.' I wrote 'Angry All the Time' before I had any aspirations towards songwriting for a living.

"And what I've discovered as far as country radio, is that there are a lot of people in Nashville who do that a lot better than me. I listen to some of those songs and have to say, 'That's a well-turned phrase. That's really well-crafted.'

"I feel like I need to go back to writing what I want to write and that presenting something different is actually my best shot at having a career. Faith and Tim cut 'Angry All the Time' because it's somehow different. And I think a lot of people -- usually with more success than I've had -- get huge and start losing what it was they had when they were hungry. The difference is I'm still hungry."

Bruce Robison may still be hungry and working hard, but it doesn't mean he hasn't taken a few minutes to consider his recent run of accomplishments. After a decade of rejection, he knows better than anybody that lightning might not strike again. He's the first to admit there are plenty of songwriters both here and in Nashville that write better songs, but haven't been lucky enough to get a star like Tim McGraw to cut one at the peak of his career.

"I try keeping it in perspective," Robison says. "I know I have to enjoy this, that it may never happen again, and that even if it did, it'll never feel like this again. My publisher is gung-ho about making it happen again, and if it does, it'll be more about relief than the pure euphoria of that first time. When I got that phone message, it wasn't pressure, it was 'Oh my God! We got a McGraw cut!' It was pure happiness."

For a songwriter as good-natured as Robison, if happiness is your first hit song, the spoils that go along with it are just as sweet.

"I'm always doing these guitar pulls in Nashville, where songwriters sit onstage and trade songs," Robison says. "And I always made fun of the guys who introduce their stuff with, 'Here's a little song you might remember, it did well for us in 1985.' It'll be fun to say, 'Here's my song that a lot of people have heard.'

"To have a hit is a legitimizing thing. It'll make me feel less like the guy at Christmas dinner where they say, 'Poor old Bruce. Kelly's doing great. Charlie's doing great. Emily is doing great. We have high hopes for Bruce someday.' It's nice to be able to hold my head up high." ![]()

Bruce Robison f^etes Country Sunshine at the Texas Union Theater, Saturday, Sept. 29, with special guest Kelly Willis.Performance