Killer Reputation

Austin's Polite History Is Marked by Spectacular Murders, Unanswered Questions

By Kevin Fullerton, Fri., Jan. 26, 2001

Amateur historian Jeanine Plumer is one of the few people in Austin who still relives the nightmare year of 1885, those long months of chilling fear that must have seemed interminable to the city's residents. A killer such as the world had never seen before was stalking the women of Austin on moonlit nights and using an axe to cleave his victim's skulls. Plumer has become so fascinated with the serial killings -- which have never been solved -- that she has put together a walking tour of the locations where each of the nine victims were found.

As she stands near the corner of Brazos and Third, in what was once a neighborhood filled with German immigrant families, Plumer points south to a parking structure covering one murder site, and north to another site, now a vacant lot. On not a single lot where one of the murders occurred, Plumer says, is a house now standing -- it's as if the killer's rampage left scars on the city that never healed, even if no one remembers their origin. Gazing up at the moonlight towers that dot central city neighborhoods, most Austin residents probably feel a touch of warm nostalgia, not realizing that city leaders raised those huge arc lights to lift the cover of darkness under which the serial killer had struck.

"The city covered them up completely," Plumer says of the killings. "This is a huge event that no one knows anything about." But though the death toll of the 1885 "Servant Girl Annihilator" murders is astounding (Jack the Ripper, by comparison, slew but five victims during his murder spree in London three years later), they were but the first of a series of Austin murders that shocked not just this city but the world. By the time Charles Whitman climbed the UT Tower with a hunting rifle and unleashed the "violent and irrational impulses" that tortured his soul in 1966, this oasis of civilization had already produced a handful of murderers who had set new standards in psychotic criminality.

"Austin is a city so known for its reputation as this sort of paradise of Texas," says Texas Monthly Senior Editor Skip Hollandsworth, who followed up on the research done by Plumer and other local historians and wrote a historical account of the Servant Girl Annihilator murders (published last July; Steven Saylor's A Twist at the End: A Novel of O. Henry is also about the murders). "It's always had that reputation from away back -- this great center of learning and relaxation and leisure. But more than other cities, it's been dotted by vicious mass murder."

The 1885 serial murders introduced the world to a new breed of criminal, who seemed unfathomably evil even a century later in the persons of New York's Son of Sam or Wisconsin's Jeffery Dahmer. But in 1885, there was no criminal profile to explain a killer who took out his violent passions on seemingly anonymous victims. The first of the Austin murderer's victims were black servant girls, one of whom he stabbed through the ear with an iron rod and raped. But then, on Christmas Eve, the killer struck at the most precious sanctum of 19th-century society: Two wealthy white women, Eula Phillips and Sue Hancock, were found lying dead just outside their homes where they had been dragged, raped, and bludgeoned with an axe.

The killings sent Austin into a frenzy. The Christmas edition of the Austin Daily Statesman cried "BLOOD! BLOOD! BLOOD!" and more than 500 citizens gathered in the streets, desperate for a plan that would stop the murders. It was arguably the most dismal Christmas morning in Austin history. "The baying of blood hounds frantically seeking the killer's scent broke into the usual chorus of Yuletide merriment, chilling holiday spirits," wrote a Statesman reporter.

In the aftermath, the husbands of the two white women were tried for their murders, though not until investigators had first roughed up some black suspects. But Messrs. Phillips and Hancock were eventually released from custody, and though plenty was learned at trial about the titillating private affairs of affluent white families, the perpetrator was never discovered.

Hollandsworth, who like other sleuths has been seduced by the unsolved riddle of 1885, says he has continued to track down descendents of victims' families, hoping to find a clue in someone's attic that will give the killer away. For more than 100 years, it seems, nearly everyone else has preferred to forget.

The Burt Murders

But it was not long after those brutal slayings that the citizens of Austin would confront yet another monstrous murderer new to the annals of crime. In fact, the same police chief who took over during the 1885 investigations, James Lucy, still headed the department when terror struck again in 1896 -- this time at the hand of a real-life Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Family members of Mrs. William E. Burt, of 207 E. Ninth, had a vague apprehension that trouble was brewing in the house that summer of 1896. Mrs. Burt (in all the contemporary news reports, her first name is never mentioned) had told them that once in the dead of night she had awakened to find her husband, William Eugene, silently staring down at her, and she had premonitions that her girls, aged two and four, were not safe. But lately, Mrs. Burt had seemed cheered by her husband's proposal to move into a smaller house while he tried to get back on his feet financially. William had fallen into some disrepute for cheating his brothers, with whom he was a partner in a cigar store. William had once fled to New Orleans when he was caught at theft and forgery. William had exhibited, as the Statesman would later editorialize, "a total disregard to moral and legal obligations in his business relations" and was regarded as "dull to a sense of business honor." But no one perceived that in the heart of this weak-willed, unsuccessful businessman a devil was raging, plotting a murder so diabolical as to draw some of the most renowned physicians in the nation to the tiny Texas capital to try and explain how such a thing could happen.

(Austin History Center C09055)

Almost everyone who spoke to Burt on Saturday, July 25, thought he acted normally. That morning he finished packing up his household goods, sold his carpets, and later announced to his brothers that he was leaving for Dallas on the midnight train. He ate dinner at the Capitol Hotel, where he sought out the proprietor for a few games of checkers, at which Burt was an excellent player. On the train, he encountered an old friend and schoolmate, who he talked with cheerily. He told everyone that his wife and children had gone to San Antonio and that he would send for them soon from Dallas.

The only person who saw him behave strangely was his cook, Minnie Simms, who later told a Statesman reporter that Burt seemed nervous, that he walked very fast and frequently burst out crying. He explained that there had been trouble the night before, Friday, and Mrs. Burt and the children had left suddenly for San Antonio. He asked Minnie to make breakfast. Don't use the water in the cistern, though, he instructed, because a cat had fallen in the night before.

Mrs. Burt's mother came calling on Sunday and was astonished when the cook informed her that her daughter and grandchildren had left town. She didn't believe the story, and called the police, requesting that they search the house. They found nothing. But the woman insisted they go back in the next day. Some neighborhood boys had told Statesman reporters that a strange smell was coming from the basement, which had an outdoor entrance. By the time William Burt's brother, Roscoe, finally entered the house on Wednesday morning, he was met with a terrible stench in the kitchen and the "ominous hum of myriads of flies" underneath the floorboards.

Mrs. Burt and the two children were found a few minutes later floating in the cistern, their heads crushed by blows to the head. Handkerchiefs were tightly knotted around the necks of all three, leading the coroner at first to presume the victims had been strangled, though later it was decided that Burt had tied the cloths to reduce the flow of blood after he struck the fatal head wounds -- the first inkling given of just how coldly and deliberately Burt had planned the murders.

Upstairs in the bedroom, no blood was found until the floorboards were thoroughly combed. Meanwhile, it was discovered that Burt had mailed two large boxes to Houston, and when police officers there confiscated and opened the containers, they found the grisly remains of Burt's crime. A bloody hatchet lay alongside blankets, sheets, and clothing sopped in blood and spattered with brains. Burt had carefully mopped up all the stain of his murder and then thrown the offensive garments into a shipping box already packed with his wife's clothes.

But the most devious part of the crime was the way Burt disposed of the bodies, first cutting off the blood flow to the head with the handkerchiefs, washing the bodies thoroughly, and wrapping them tightly in blankets. It was suspected that Burt had planned, in case he met Minnie returning to the house that evening, or if any of the neighbors saw him enter the basement door, for it to appear that he was merely toting rolls of carpet.

The cold premeditation of it all had the Statesman's editors fumbling to express their astonishment that such evil had crept into their quiet town. "Murders that made Paris famous, when the Seine was wont to give up its dead each morning, were never more heartlessly cruel, and never in their perpetration was there more utter emancipation from every restraint of conscience," the paper wrote the day after the bodies were discovered.

Burt was convicted and sentenced to die in October of that year, but just before he went to the gallows the governor ordered that Burt be given a new trial to determine if he was insane. That trial, in 1898, shared headlines with the rumblings of America's impending war with Spain. The Statesman printed full court transcripts each day, as well as a drawing of Burt's hand with commentary from a palm reader. Physicians argued tediously for long hours about the nature of Burt's mental health. His skull was measured, but nothing found amiss. Letters he had written in prison were examined and found perfectly cogent. Jailers testified that they had spied on him and observed no unusual behavior. On the witness stand, doctors fumbled around with the term "moral insanity," but could not explain how a person could seemingly have all his faculties in order save the one that guarded against evil thoughts and deeds. One argued that there must be such a thing as temporary insanity, as everyone knew that a person might strike a dog or a horse when there was no rational reason for doing so.

Burt's brothers testified that Burt had suffered major trauma when his father died while he was still a teenager. The boy who had once had a sunny disposition became withdrawn and ill-tempered after that, the brothers said. Clearly, William Eugene Burt had been emotionally cut off from friends and family for many years, but no one knew the ravages the condition had wreaked on his psyche. A letter he wrote, printed in the newspaper shortly before he was hanged in 1898, illustrates the depth of his schizophrenia. "The outraged law is still outraged," Burt wrote, because the real perpetrator of his wife's murder was "already punished by forces not of the law.

"Great God be thanked," he wrote, "the hellish brute that took from me the sweets of life, that snaped [sic] the human cords of my heart, that took from me and sent to heaven my loved ones, will never see the fulfillment of the ends of lawful justice. ... How happy to lay and dream ... to hear the howls and shrieks and screams of his tortured soul."

Burt's case was a premonition of an even more publicized murder that would shake Austin in 1935, when Howard Pierson, a brilliant university student, became the nation's most infamous parricide when he lured his mother and father to a rural road west of the city and shot them. Howard's father, William Pierson, was then a justice on the Texas Supreme Court. That case would capture national headlines on and off for 30 years, principally because Pierson escaped twice from mental institutions and would disappear for years at a time before being recaptured. (A member of a prominent family, Pierson had never been subjected to the indignity of fingerprinting.)

From young Pierson emerged the story of a youth so troubled and delusional that he believed the world would someday forgive him for a crime he felt he had no choice but to commit, convinced that his parents were preventing him from scholarly research that would benefit humankind. As fate would have it, Pierson would finally be certified insane in 1963, only two years before another clean-cut schoolboy, James C. Cross, strangled two University of Texas sorority girls, the first in a wave of student slayings in the 1960s.

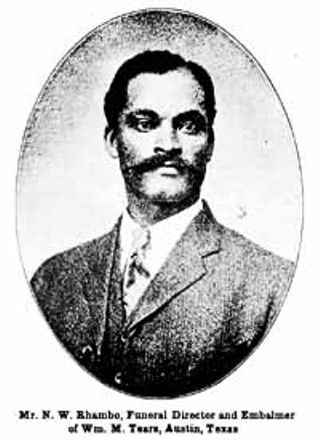

Who Killed Nathan Rhambo?

A few years before the Pierson slaying, yet another murder occurred here which didn't make national news, instead garnering only a few lines on the front pages of the Statesman. But the Rhambo murder quietly soured racial relations in this town for years, and its secrets remain closely guarded.

(Austin History Center A287 Ab)

Only a few blocks off the route Jeanine Plumer follows in her tour of the 1885 murder sites stands an old building in which the ghost of a murdered black undertaker is said to still be laughing. He's apparently impressed with the irony that he became his own client (see "Shades of the Past," page 44), or perhaps he laughs at his own audacity -- at the affront his wealth must have posed to white Austin -- and at the scandal he was causing through his rumored affair with a white woman. Though a young black man was sent to the electric chair for the 1932 kidnap and murder of Nathan W. Rhambo, it's safe to say the deeper truth behind that slaying -- possibly in retaliation for his interracial love affair -- has never seen the light of day.

Nathan Rhambo was an extraordinarily handsome man, known also for his impeccable manners and good taste. Perhaps that's why as a young man he was singled out to be the protégé of William M. Tears, one of the most successful black undertakers in the entire South. While others who carried the name Rhambo at the turn of the century were typically porters, coachmen, and yardmen, Nathan Rhambo went by the much finer title of embalmer, a profession in those days esteemed nearly as highly as law and medicine.

Though Rhambo still suffered the ignominy of the lowercase "c" (for "colored") following his name in the city directory, he didn't let that get in the way of making money. Austin's race relations, like those of any other Southern city, were stunted under Jim Crow, but the city was relatively free of lynch mobs, like the one in Missouri that dragged a black man accused of assaulting a white girl from a county jail and burned him in the town square in 1932.

When Rhambo went to work for Tears, in 1901, black businesses were thriving in the east end of downtown, and Rhambo soon took his place as one of the foremost funeral directors in the black community. He cultivated a genteel interest in hunting, an interest that in those days could only have been indulged by a few black men, in whose hands the sight of a gun wouldn't bring policemen down like crows. He married, was a member of Third (now Ebenezer) Baptist Church, and had a reputation as "perfectly sober -- never smokes, drinks, or chews." On the other hand, Rhambo wasn't shy about flaunting his wealth. After his murder, the Statesman reported that he was reputed to carry around large sums of money.

Rhambo left Tears' establishment and opened his own funeral home sometime between 1915 and 1920. The business thrived, and by 1929 Rhambo's funeral home was one of the few listed in bold type in the city directory, advertising "Superior Ambulance Service" and "Courteous Attendants."

But on the night of June 21, 1932, Rhambo saw his last customer. A young man dressed in a gray suit and Panama hat called upon him and asked the 55-year-old funeral director to escort him north of town to fetch a recently deceased relative. The two left in Rhambo's black Buick sedan, and that was the last time Rhambo was seen alive.

He was found early the next morning in his car by the side of the road near Dawson, about 130 miles from Austin, shot through the head and severely beaten. Within 24 hours, state Rangers had a suspect in custody: Carl Stewart, identified by employees at the Rhambo funeral home as the man who called on Rhambo the night of his death. Police also arrested two of Rhambo's employees, saying the three men conspired to rob the wealthy man -- though a detail that slipped into the newspaper was that Rhambo was still wearing a diamond ring on his finger when he was found. Since Rhambo was a prominent black businessman, the circumstances of his death were reported in the papers, but he received no obituary in the paper, not even a funeral announcement.

Stewart was held eight days in police custody without seeing a lawyer. He eventually signed a confession, drafted by a state Ranger, but at his trial Stewart claimed he signed the statement after being tortured for days in a Waco jail. Stewart claimed he was given almost nothing to eat, wasn't allowed to sleep, and was strung up by a pair of handcuffs until he fainted from the pain.

Surprisingly, the trial that commenced in October was not to be the usual sham trial for an allegedly murderous Negro. Somehow, Stewart managed to retain the services of not one, not two, but three prominent white Austin lawyers. And what those lawyers did in Stewart's defense is historic: They questioned the veracity of the white Rangers who claimed Stewart's confession was given voluntarily, and accused the Rangers of abusive coercion. They questioned the Travis County district court's jurisdiction over the crime, and tried to have the trial moved out of the victim's hometown. They protested when Rangers who were serving as the state's witnesses were allowed to remain in the courtroom while the defendant's witnesses were on the stand, claiming the officers intimidated their witnesses and improperly conferred with the prosecuting attorney while he was giving cross-examination.

In short, the attorneys challenged the integrity of a white court on behalf of a black murder defendant. Whether this was a first in Austin is unknown, but in protesting the unfairness of placing Stewart before an all-white grand jury (they actually used the word "discrimination"), the attorneys pointed out that a black person hadn't served on a grand jury for 26 years, even though "persons of African descent" comprised 10% of registered voters in Austin and Travis County. It's likely they wouldn't have trumpeted this point had it been a standard complaint.

The lawyer's efforts did no good, of course. The jury deliberated only 35 minutes before declaring Stewart guilty and sentencing him to the electric chair, only the second such sentence to be given in Travis County. Judge C.A. Wheeler dismissed all of the defense attorneys' objections to the trial's conduct, as did an appeals court the next year. Wheeler did not even find it prejudicial that when urging the jury to choose the death penalty for Stewart, the district attorney impressed this thought upon the jurors: "Carl Stewart is a Negro. This time he confined his crime to one of his own race. Do you have any assurance, if you turn him loose, that the next time he won't go out and kill some white man for money?"

The prosecution had no hard evidence against Stewart, only the witness testimony that he had accompanied Rhambo the night of his murder, and the dubious confession. Nevertheless, Stewart died by the chair on December 29, 1933, only one month after his appeal failed.

And with Stewart's death, the full story of who really killed Nathan Rhambo went to the grave. While held by the Rangers, Stewart implicated some other black men in the crime, and even if he was involved in the murder, it's likely he was working for someone else, possibly a jealous husband or other relative.

How else could 23-year-old Stewart have afforded the services of three white lawyers unless he was either (1) flush with payment for pulling a hit, or (2) connected with a wealthy family that promised to help him beat the rap if he got caught? And does the fact that someone actually tried to follow through on such an impossible errand indicate that in fact his customer was not white but perhaps a wealthy black person? The newspapers never reported any personal details about Stewart, not even where he was from, and other crucial records such as witness testimony weren't kept, so it's impossible to ascertain Stewart's true role in the killing. It's said that people who remember the case still live in Austin, but for 70 years no one has wanted to talk about it. Unless someone steps forward with forgotten evidence, the true intrigue behind Rhambo's death will never be known.

![]()

Today, when the remaining moonlight towers erected by our forebears a century ago come alight in the evenings, their pale fluorescence is nearly swamped by the glare from hundreds, thousands, of mercury bulbs. Just as those aged sentries could not always save the city from the darkness that afflicts the thoughts of humankind, neither can the illumination thrown off by our wealthy, progressive era. The pursuit of scholarship didn't prevent Whitman from climbing the UT Tower, nor did Austin's lively civic and philosophical debates defuse the murderous rage that led to the 1992 yogurt shop killings, the 1997 abduction and drowning of Juan Javier Cotera and Brandon Shaw, or the Barton Creek rapist. Austin continues to promote its reputation as a center of cultural achievement, but history reminds us that the impulse to violence can be highly resistant to civilizing influences. ![]()