The Hottest Race in Texas

The David Fisher-Todd Staples Senate Contest in East Texas Will Decide the Fate of the State Senate -- and the U.S. House

By Michael King, Fri., Oct. 27, 2000

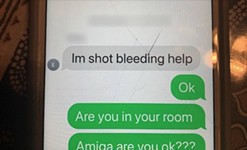

On the evening of October 17 -- while much of the nation was watching either George W. Bush and Al Gore impersonate Disney World robots, or the Yankees finally pummel the hapless Mariners into submission -- a real, live, up-close and personal political event was in progress up in East Texas. In the auditorium of Frankston High School in Anderson County, the Tyler League of Women Voters had assembled several state and federal candidates for a "Four-County Forum" (Henderson, Smith, Cherokee, Anderson), allowing the voters to gather and evaluate a sizable brace of their current or potential representatives. Not every invited candidate was able to attend. With Congress still in session, U.S. Reps. Ralph Hall and Pete Sessions were in D.C., and neither District 2 Senator David Cain nor his opponent, Bob Duell, could make it. But that was just as well: There were eight candidates, a moderator, and seven (count 'em, seven!) reporters from the also-sponsoring local media on the stage. Indeed, for a few early minutes it appeared that -- just to make enough room -- the audience would have to exchange places with the candidates.

Those on hand included the candidates for:

Newton and Berman were both entertainingly high on the David Letterman political scale (otherwise known as the Boob Quotient). Newton apparently thinks he is running not against Ralph Hall but against the late African dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, since he proposed nothing but the abolition of all foreign aid "to countries that don't support our interests" like Zaire. Later he promised to return "Reagan [his new infant daughter], Bush, and Cheney" to Washington. Berman, a retired lieutenant colonel, oil company PR executive, and former Arlington City councilman, is an anti-tax crank whose distinguished House record is comprised of one bill: an amendment to the sales tax code to exempt specialized medical eating utensils. Berman stoutly advocated replacing all progressive income and property taxes with a national consumption tax, and later grimly defended his last-session "protest" vote against federally subsidized health insurance for poor children (the CHIP program) because, he said, it is a "giveaway program for the middle class." By thankful contrast, Bowen, a school bus driver whose wife is a teacher, and Hopson, a Palestine pharmacist, distinguished themselves by quiet and assured good sense throughout the proceedings, even defying a central plank of the East Texas political gospel by supporting a woman's right to choose. (Bowen has slim hopes in Berman's predominantly Republican district, but Hopson is said to have a good chance in District 11).

The Real Action in East Texas

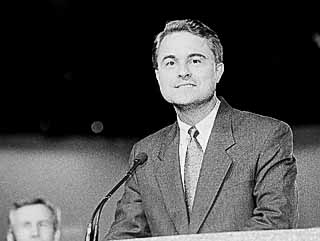

But the real action was the state Senate District 3 race, which features Democrat David Fisher of Silsbee against the Republican Palestinian Todd Staples, who is vacating the District 11 House seat to run for the Senate. Most questions from the audience and reporters were directed at Fisher and Staples; it was Staples and Fisher who drew the most cheers (or boos); and The Austin Chronicle was not the only out-of-district media present. The Wall Street Journal was also monitoring the festivities, here before perhaps 100 people, at this little crossroads town on State Highway 155, midway between Tyler and Palestine.

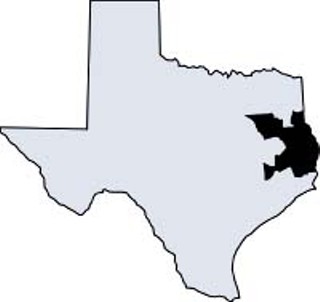

We were all here because of the statewide and nationwide importance of the District 3 race, which has the potential to tip the current majority balance in the Texas Senate from Republican, now 16 to 15, to Democratic. Moreover, should Governor Bush win the presidency and Lieutenant Governor Rick Perry get a social promotion to the Governor's Mansion, the District 3 election could determine the next presiding officer of the Senate (still likely to be an establishment stiff, as the Senate elects one of its own, but almost certainly one with more independent sense than Very Lite Guv Perry). More importantly -- assuming, as is expected, the Democrats retain their narrow control of the Texas House -- a majority in the Senate would give the Democrats a strong advantage in the battle over statewide redistricting.

Redistricting, in accordance with the just-completed 2000 census, could determine not only the partisan make-up of the statehouse for at least a decade, but also have a dramatic effect on the state's U.S. congressional delegation -- and ultimately, the shape of the U.S. Congress. The Texas congressional delegation is currently made up of 17 Democrats and 13 Republicans. Redistricting could shift a half dozen or more seats toward the Democrats or Republicans, so the party that controls the redistricting process in Texas will have a lot to say about who controls U.S. House of Representatives for the next decade.

"This race is critical for Texas," Austin's state senator, Gonzalo Barrientos, told the Chronicle. "Having a Democratic majority in the Senate will not necessarily determine the fate of redistricting, because it is always a negotiation situation. But it would give [the Democrats] a little more leverage, and a strong psychological advantage. And it would also mean one more person to join us in either supporting good legislation, or stopping bad legislation, because of the two-thirds rule." Under Senate rules, no legislation can be brought to the Senate floor unless it already has support of two-thirds (21) of the 31 senators. In other words, a coalition of any 11 Senators can stop a bill in its tracks.

With all this at stake, the Fisher-Staples race has become so important to the two major parties that they and their high-dollar supporters are pouring unprecedented amounts of money into the campaign, making it almost certainly the most expensive state Senate campaign in U.S. history. According to their Ethics Commission disclosure filings, at last count (October 11), both campaigns had accepted well over $1 million, with Staples apparently leading with about $1.4 million to Fisher's $1.2 million. With the election a couple of weeks off, there will certainly be some late money -- Staples is expected to spend in all about $2 million, Fisher about $1.5 million. In addition to Republican Party bucks, Staples has collected much from tort-reform PACs and right-wing sources like San Antonio tycoon James Leininger. With lots of help from his own party, Fisher is also taking in checks from wealthy trial attorneys, including Beaumont's Wayne Reaud, one of the big winners in the state's tobacco litigation (for more detail, see "Who's Buying S.D. 3?," p.38) Both campaigns insist they have enough money to do what they need to do, in a race that will probably come down to "turnout" -- getting out the vote.

Senate races weren't always so capital-intensive. For comparison, former District 3 senator Bill Haley (now a legislative consultant) was asked how much he used to spend on a campaign. Haley, who was a Democratic senator from 1988 to 1995, says that in his first primary campaign (when the Democratic primary effectively determined who would fill the office) he spent $340,000, and his opponent spent about $300,000. "In my second Senate campaign, which was a November campaign ... my Republican opponent and I spent about $400,000 altogether." Haley said the influx of money is equally apparent on the House side. "The most I ever spent on a House race," he said, "was $14,000 -- and $2,000 of that was essentially an afterthought to clear out the account, after the race had already been decided. Generally I spent about six or eight thousand dollars, and many of my colleagues say they never spent more than $3,000 or $4,000." Haley mentioned on East Texas House race in which one candidate spent $200,000. "That was unheard of, just a few years ago," he said.

Nationalizing a Regional Election

Out in East Texas, party regulars are certainly aware of the stakes riding on the District 3 race. They notice the visiting reporters and the money, which has also affected hotly contested House races that might have a strong effect on turnout. Those include the northern area District 11-Palestine (Staples' now-open and traditionally Democratic seat), where Democrat Hopson is battling Republican bank vice-president Woodard; the mid-East Texas District 9-Nacogdoches, where far-right Republican incumbent Wayne Christian is being strongly challenged by Nacogdoches County Sheriff Joe Evans; and the southern District 18-Livingston, where Democratic incumbent Dan Ellis is once again facing a well-funded Republican challenger, Ben Bius. (The mostly rural Senate District 3 is spread north and south across East Texas, including all or parts of 17 counties, from just outside Tyler to the edge of Beaumont. Fisher expects to do well in traditionally Democratic rural areas, and Staples is expecting major support in wealthier suburban areas, especially the white-flight Houston suburbs of Montgomery County.) And there is the additional wild card of the presidential race, and whatever effect an incumbent Republican governor running for president might have on both turnout and down-ballot choices.

Yet both the Staples and Fisher campaigns at least rhetorically insist that the Senate race will be won on important East Texas issues -- most prominently, health care, education, correctional officers' pay, and East Texas water rights. Those four are the issues both candidates are banging away at on the campaign trail, although admittedly with differing emphases. "It's in my opponent's interest to nationalize the race," Fisher told the Chronicle, "while I want to localize the race -- because people don't give a rat's patootie about what effect it's going to have on the national political situation. What they want to know is how it's going to help East Texas." Just before the Frankston forum, Staples was telling reporters much the same thing, but his campaign materials -- especially his television ads -- inevitably feature either a smiling George W. Bush, or a sneering reference to the Clinton/Gore administration. Staples is obviously hoping that the governor has longer coattails in 2000 than he did in 1998, when statewide offices went Republican but there was little ripple effect in the Senate and House. Two years earlier in Senate District 3, Republican Drew Nixon defeated his Democratic opponent by 387 votes. But with Nixon having moved on in disgrace after his 1997 Austin arrest and conviction for soliciting a prostitute and illegally carrying a weapon, it would seem that the Senate seat is wide open for a Democratic revival. "The majority of elected officials across the 17 counties, especially local officials, are still Democrats," Fisher told the Chronicle, "so if we can get out our voters, we should be able to win across the whole district."

So to an extent, David Fisher is running against Bush and Austin, and Todd Staples is running against Gore and Washington. Oddly enough, Staples is also running against Beaumont. Staples, who has lived in Palestine all his life, charges that his opponent "moved into the district" (from Beaumont to Silsbee) only three years ago, to "set up" a run for the Senate seat. "David Fisher is a carpetbagger," says Staples repeatedly, "an outsider who doesn't understand or speak for the people of East Texas." One of Staples' most recent TV commercials (the candidates have definitely spent a bundle enriching East Texas broadcasters and the Austin ad agencies that feed them sentimental political bilge) features some young children who, the ad claims, "have lived in East Texas longer than David Fisher."

But Staples' attack on Fisher's current homestead has some obvious problems. While it's literally true that three years ago David Fisher moved his home from the city of Beaumont (where he has his law office) to Silsbee in Senate District 3, the southern boundary of District 3 just happens to be the Beaumont city line. Silsbee is perhaps 20 miles up the road, and to any voter who can read a map or ride a highway, Beaumont, while technically not in the District, is as much a part of "East Texas" as is Palestine. More importantly, Fisher has deep family roots in what is often called Deep East Texas, going back into the 19th century, and his grandfather, the late Joe J. Fisher, was a U.S. District Judge for the Eastern District, from 1959 until his death this year. Indeed, because of his family history as well as his own law practice (he has defended several District 3 counties and municipal governments in various kinds of civil litigation), David Fisher may well be better-known throughout the entire district than his Palestine-based opponent. "People who live in East Texas travel in and out of Beaumont all the time," said Fisher. "It's all part of one region. And they see me all over the district, as well. When they hear Staples describe me as an 'outsider,' they think it's just silly."

Yet when asked last week whether he truly thought the term "carpetbagger" accurately described his opponent -- since Beaumont is hardly Boston -- Staples responded, "Residency is an issue! Residency is a legitimate issue!" It is a theme he harps on in his advertising, and one he returned to strenuously from the stage in Frankston. (Both candidates sidestepped the notion that in the South, the term "carpetbagger" still carries racial connotations originating in Reconstruction, but Gary Bledsoe of the state NAACP commented drily, "I sure would want to be careful of the context in which I would use that word.") For his part, Fisher repeatedly describes Todd Staples as "lacking in leadership" because, he says, Staples does not have the fortitude or independence from the Republican leadership "to stand up on behalf of East Texas, when it means going against his party leaders." Former senator Bill Haley, whose own precise East Texan manners are legendary, said that he would counsel both candidates that in his experience, personal attacks of any kind simply do not work among East Texans. "I once had to pull a radio commercial written by one of my campaign managers, that I believed was the least bit negative about my opponent," Haley recalled. "And in my humble -- though correct -- opinion, East Texans have a pronounced antipathy to personal attacks, and such attacks are as likely as not to backfire against the attacker."

Health Care, Prisons, and Water

Setting aside the campaign-driven animus now evident between the two men, Fisher and Staples do not appear terribly far apart on what they think are the important issues. In discussion, both candidates emphasize health care, education, the prison situation, and the protection of natural resources. Their widest differences appear over who would better deliver for East Texas on those issues. For a rural region which has often been designated "medically underserved," both promise better access to health care and prescription drugs, and to attempt to reduce insurance costs (especially for teachers). Both declare education a priority, and both are apparently dubious about vouchers for private schools. There are now 11 Texas Department of Criminal Justice prison units in the district, which employ 10,000 district residents. Indeed, prisons are now the region's biggest single employer, having moved ahead of sizable agriculture and logging concerns, and any kind of manufacturing. Both candidates insist they will raise pay for correctional officers -- who are visibly organized, angry, and registered to vote. Finally, both Fisher and Staples insist that they will defend East Texas' abundant water resources -- increasingly desired by outside interests, and also under regulatory siege by the Environmental Protection Agency.

The distinctions are in the details, especially on education and water.

From the beginning, Fisher has forthrightly opposed school vouchers, and from an interesting perspective. He says vouchers would specifically be bad for rural East Texas (which has few private schools of any kind), because they would certainly weaken the public schools and "simply transfer public money to wealthier suburbs, where most of the private schools are located." He also thinks vouchers would be bad for private schools, "because government money doesn't come without strings." Staples responds that he opposes "mandatory" voucher programs -- which he now distinguishes from the pilot voucher program supported by Governor Bush and the Republicans, and which Staples voted for last session (it failed), and which is the pet project of one of Staples' biggest financial supporters, James Leininger. Staples insists that the pilot program (which would have covered some of the biggest school districts in the state) was "voluntary" (in his version, school districts could opt out). But the fact that Staples has had to run away from his own record on vouchers suggests that what sells with Republicans in Austin won't necessarily play with voters in East Texas. That fact, at least, bodes well for the Fisher campaign.

Similarly, Staples spent part of the Frankston forum trying to convince his audience he will fight the Republican leadership's recent attempts to strip the "junior water rights" provision from state water law. The provision (recently upheld in state courts) potentially allows East Texas to sell its abundant water to outside buyers (e.g., the city of Houston), with the restriction that such transfer obligations would be "junior" in times of drought (and the water would thereby remain as necessary in East Texas). Recently, the Senate Natural Resources Committee, chaired by Lake Jackson Republican Buster Brown, has argued that the junior rights provision should be eliminated -- theoretically allowing a "free market" in water. All eight East Texas candidates -- Democrat and Republican alike -- loudly denounced such a move, to the point that at times it appeared they were all in fact running against Buster Brown. Asked about the controversy, Senator Brown's office issued a statement explaining that he believes the continuing inclusion of the junior rights provision in Senate Bill 1 (the Brown-Lewis Water Management Plan) "has caused a shift in focus from surface water to groundwater ... putting additional pressure on an already depleting source." Brown argues that only "conjunctive use" of water sources can prevent extreme water deficits, and therefore "as a planning tool ... water planners need inter-basin transfers of surface water, without harming the basin of origin." Whoever shows up in Austin next year from Senate District 3, it's clear that he'd better be ready for the water wars.

Earlier, a spokeswoman for Staples had told the Chronicle that her candidate "led a walkout" of House representatives rather than support Brown's proposal. Staples didn't attempt to sell that uncertain bit of Capitol history at the forum. He did insist that he would protect East Texas water rights, leaving Fisher to smilingly suggest that East Texans would be at best gullible to believe his opponent. When Buster Brown and others come calling, Fisher suggested, Staples will not be able to withstand the pressure of his party leadership. "He's either going to have a 100% Republican voting record," Fisher told the Chronicle, referring to one of Staples' early campaign claims, "or he's not. He can't have it both ways."

Finally, on the extremely hot-button issue of a pay raise for correctional officers, Staples has been beleaguered at every public forum by angry and assertive officers, who say they are tired of waiting for serious action. At a Fisher cookout in Center last July, William Cox, a sergeant at the Skyview/Hodge Unit in Rusk, said that not only are officers poorly paid (after 11 years in TDCJ, Hodges makes about $29,000 a year), prison staffs are so short-handed they are working in increasingly dangerous conditions. There are 2,000 unfilled positions system-wide. "Inmates know the situation," Cox said, "and they take advantage of it." With increasing gang activity, he explained, officers become fair game: "Officers get caught in the crossfire. They'll try to take you out, to get to that inmate that they're after."

Staples takes credit for a "pay raise" enacted during the most recent legislative session. But Cox and other officers say that was a "step-level adjustment" that had been in the works for years, that it only affected officers with several years seniority, and that in any case it amounted to only $80 to $130, "most of which immediately got eaten up in an insurance increase." Asked why, under such conditions, he stays with the TDCJ, Cox replied, "I've got too many years in now ... I'm a carpenter by trade, but working on my own I can't get benefits -- insurance for my family, or retirement. I'm at the point where I need to have something to look forward to."

Three months later in Frankston, Cox's words were echoed by Linda Harris, another officer from Hodge and one of the organizers of the Rusk Correctional Officers Coalition, which has held several public forums for officers to meet the candidates. During one such event, held at a Palestine auditorium in Staples' House district in September, several hundred officers roundly booed the candidate when he tried to defend his record on their issues. "We're 46th on the national pay scale," said Harris, "or $10,000 under the national average -- with the second largest inmate population in the nation [after California]. They keep telling us they're going to do something about it. We're tired of waiting."

Cox and Harris said that in the past, the officers' worst enemy has been their own apathy, but they insist that passivity has ended. "We [the RCOC] haven't endorsed any candidates," said Harris. "We've only organized officers to register and vote. Before, we only voiced our complaints to each other, but now we're 90 to 95% registered, and our vote will count." Staples, as the incumbent House member, may reasonably fear that the officers' wrath will be visited on his head November 7, while Fisher has the advantage of the newcomer on this issue. He offers a plan to get to the national pay average within three years; Staples says he would take four years, but that his plan is more "realistic and financially feasible."

Brian Olsen, executive director of the state Correctional Employees Council 7 (the officers union), based in Huntsville, emphasizes that a pay raise (which he insists could and should be enacted immediately) is not the only important issue. "We're also talking about hazardous duty pay, training of new officers, safety, and treatment by supervisors," Olsen said. "Some of the officers who leave say, 'I'm tired of being treated worse than the inmates.'" Olsen acknowledges that as a House member Staples has been helpful on some issues, including the anti-"chunking" bill (which made throwing feces or bodily fluids at officers a felony assault) and on compensation time. "We're not endorsing candidates, and I would guess our members are about 50-50, Fisher-Staples. But Staples' problem is that he and the other Republicans say they support our pay raise. But they gave it away instead, in order to give the governor his campaign tax cut. Staples can't have it both ways."

Officers might be made additionally skeptical about Staples' record on wages by another remark he made during the Frankston forum. Asked about his position on raising the minimum wage, Staples responded that government had no business setting wages or rates. "We should solve wage problems by education programs," said Staples, "because the minimum wage doesn't do working families any good." Staples went on to argue, mysteriously, that abolishing the minimum wage would somehow make wages rise -- a position not defended even by the Republican King of the Wage Slashers, Congressman Dick Armey, who simply argues that lower wages mean more jobs. The day after the Frankston forum, the Fisher campaign was eagerly calling attention to Staples' latest economic proposition, for an East Texas population of which 56% of families earn less than $25,000, and 19% of the people live in poverty.

There is, however, one residency issue which has allowed Staples to take the high ground against his opponent. Some weeks ago in Polk County, a few local Democrats challenged the voting rights of some 9,000 recreational vehicle owners registered to vote in the county. According to the challengers, the RV owners (said to be mostly from out of state, and mostly Republican) were only using a Texas address to evade higher taxes elsewhere. Many of the voters belong to an RV club called the "Escapees." The court challenge alleged that for many Escapees, the group's official Livingston PO box address was only a mail drop for nonresidents who shouldn't be allowed to vote in the county (where they now comprise nearly 10% of the registered voters). However, the Texas residency law is sufficiently vague that the challenge was quickly rejected in the courts. Before it was, Staples alleged (based on circumstantial evidence) that this attack on voting rights was a Fisher campaign operation, set in motion by Fisher's political allies and his law firm. At the forum, Fisher reiterated his denial, but Staples called the voting challenge "a malicious act by desperate people," and cited the involvement of the Austin political consultant firm Emory, Young & Associates (which has also worked for Fisher). In any event, the Polk County Escapees will be voting November 7, and whoever was behind the challenge, wrote Austin columnist Dave McNeely, may have only succeeded in "stirring up an ant's nest."

Afterward, Fisher said he regretted the whole episode, but that the RVers will indeed be allowed to vote, and that for Staples to accuse his campaign of organizing the challenge was simply an attempt to "sensationalize" the story and to divert voters from the real issues. It's not clear what the votes will mean for a district-wide Senate race, where more than 200,000 people will vote. But in Polk County and House District 18, Democrat Dan Ellis may well be dreading the snowbird vote.

The Western Edge of Dixie

Even a casual visitor to the region -- "the western edge of Dixie," Bill Haley calls it -- might think it would be impossible to talk about Deep East Texas for more than a few minutes without talking about race. Black and white relations are ingrained in the history and institutions of the place, where it's barely been a generation since official segregation ended, and unofficial segregation -- and the deep-seated, institutionalized racism that accompanies it -- goes on and on. But you wouldn't necessarily know that by talking to white politicians, who can speechify for hours without ever mentioning the subject. Most of them did exactly that at the Frankston forum, where the reporters, the forum organizers, and all the candidates except Regina Montoya-Coggins were white, and only a handful of African-American voters were in attendance. Except perhaps for water rights (for which one of Staples' designated villains is Houston's African-American mayor, Lee Brown), all of the campaign's major issues touch directly on minority group interests, although sometimes in a contradictory way: e.g., the focus on correctional officers' pay (and prisons generally) quietly sidesteps the reality that far too many TDCJ prisoners are black or brown, and the state is inexorably expanding its institutional and economic interests in keeping them incarcerated.

In July, Fisher told me that prison money "would be much better spent on early intervention with children and at-risk populations." And he said he was troubled by the whole question of building an industry "upon the enslavement of people." "You don't solve crime," he said, "just by putting people away. ... We can't afford to build more prisons when we can't pay the people already working in the prisons enough money for a living wage." But there was none of that in more than two hours from the Frankston High School stage, where the putative voting rights of transient RV owners received more sanctimonious attention than did jobs programs for impoverished East Texans. To his credit in the district that contains Jasper, Fisher reiterated his support for hate crimes legislation (to the bristling rejection of the Republican side). And in an otherwise utterly clichéd discussion of redistricting ("Let's do it fairly and in a nonpartisan fashion," was the unanimous sentiment), only Bill Bowen firmly pointed out that whatever is done in redistricting, it should not further dilute minority voting rights.

In interviews with NAACP members from around the district, the hate crime legislation came up regularly, as did redistricting, and jobs (far more often and with more emphasis than in the Frankston forum). Booker Hunter, president of the Jasper NAACP, said that in some ways, in the wake of the James Byrd Jr. lynching last year, "things have gotten a little better between blacks and whites. Some white people just couldn't go for that, and it changed them." But African-Americans definitely noticed when, during the presidential debates, Gov. Bush couldn't get the details right on the prosecution of Byrd's murderers. And some things in East Texas, Hunter added, remain unchanged. "When white schoolkids do something wrong, it's a school disciplinary matter," he noted. "But when black schoolkids do something wrong -- particularly if it affects white children -- they call the police."

Bill Haley recalled that in his experience, the biggest mistake white politicians often make in approaching the black community is to believe that black voters can be "bought" -- with jobs, or patronage, or political favors. "What the black community wants is to be recognized, to be included, to be considered for their own work and talents, for what they bring to the larger community -- as is only their right. In many ways, they are more politically cohesive, on their issues, than other groups. But they want to be treated as part of the larger community."

The words "East Texas" cover a lot of ground, literally and figuratively. Senate District 3 is a big district, with many competing interests, many of them flatly contradictory. There is simply no way one officeholder can hope to respond equally to suburbanites in the south, factory workers (and factory owners) in the middle, loggers (and lumber barons) and poultry farmers (and poultry tycoons) in the north, plus teachers (and school boards) and correctional officers (and prisoners and their families) all over. East Texas is also, more often than not, surpassingly beautiful: lushly green, rich in rolling hills and piney woods, and teeming with wildlife. And rich in people too: From Beaumont to Tyler, Montgomery to Carthage, they don't come any friendlier or more interesting.

Whoever wins the November election -- David Fisher or Todd Staples -- will assume a considerable responsibility. The new senator will be carrying a heavy symbolic burden as well -- because as East Texas goes, so may go the nation. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.