Countdown to Ecstasy

A New Drug for a New Millennium

By Marc Savlov, Fri., June 9, 2000

I Feel Love

I'm sitting in one of the myriad coffee shops on Congress Avenue -- slouching, actually; it's a sunshiney spring Saturday morning, and the previous night keeps doubling back on me. Blending with the almost imperceptible ambient babble from the shop's other customers is the voice of the young man seated across from me.

His hair is jet black, cut close to the bone, accenting his crystalline blue eyes. From his medium build to his flaming A.D. 1 trainers, he could be any thirtysomething semipro something-or-other you see crowding downtown Austin every day of the week.

Right now, though, he's reeling off his current lot in life: 32 years old, University of Texas graduate, single, emotionally and physically stable, successful in a Austin-based dot-com startup company making God knows what.

"Utterly normal," he tells me.

We're here this morning, he and I, to discuss his former drug of choice, Ecstasy, or if you're a chemical engineer, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine. This guy, this normal-as-the-day-is-long guy is flashing back to his first Ecstasy trip: May 1985, before the drug went Schedule I, before "America's War on Drugs," before many of the current crop of Ecstasy users were even born.

As he begins taking me back to that almost mythical first time, his voice ratchets upward in tone, the words coming quicker, excited at the recounting of such an obviously glorious experience. His body language echoes his words. Between swallows from an oversized mug of cappuccino, this is his story:

"Some friends of mine and I had gone down to the Lizard Lounge -- where that retro club Polly Esther's is now -- wanting to try some Ecstasy. We wanted to see what all the fuss was about. The word was that it was just, you know, very cool stuff. Very safe, not too trippy. Fun. My girlfriend scored some pills, these large whitish tablets, like horse pills almost, from some guy that was just selling them right there on the street in front of the club. I mean right out in the open -- $12 a pop.

"So we get the stuff and go into the club, buy some orange juice and chew/swallow/chase. Nasty, nasty flavor. Horrible. After that, we kill some time dancing, walking around, just sitting there waiting for the stuff to do whatever it was going to do. We were nervous, too, but everyone had assured us that this was a cool place to do it.

"After about half an hour or so, my girlfriend and I went outside to the alley across from what's now the Alamo [Drafthouse] Theatre and sat down. And I vividly remember -- like it was yesterday -- sitting on a little, like, gas main that was mounted against the wall at the mouth of the alley, with people going by, drag queens, students, and suddenly being very, very conscious of my vision becoming amazingly good.

"The street lights got brighter, I could see the stars, car lights, even the shadows in this alley were, you know, moreso. And I felt this tingle that began in my fingers and spread all over my body, coming in waves, just this indescribable feeling of aliveness.

"It was if the nerves in my skin had been dormant all these years and were just now waking up and stretching. Just like that. And after this initial rush of pleasure came an overwhelming -- and I mean over-fucking-whelming -- feeling of total and complete positivity. Any and all fears I had harbored about doing my first drug were waylaid instantly. It was pure bliss, but it didn't knock me off my feet, or feel scary in any way.

"My girlfriend -- who was right there with me -- and I went back inside the club and told our friends we were going for a walk. We spent the next four, five hours just walking around downtown Austin. We went to the banks of Town Lake and lay in the wet grass and watched the stars and cuddled. And we talked. We talked for hours. We talked about everything. Everything. It was probably the best, most open and honest conversation I've ever had with anyone in my entire life.

"And then a few hours later we kind of plateaued out on this drug experience, went home, and ended up staying together for almost our whole college career. Which is not something you find too often in freshman couples, you know? I suppose that wasn't due to doing this drug, right, but it didn't hurt the situation at all.

"It was a life-changing experience. And I mean, like, for the better."

Thrills, Pills, and Bellyaches

Those are heady words, ones that are repeated ad infinitum wherever people talk about Ecstasy. There are more grinny, happy X-tales floating around Austin than there are wannabe filmmakers. Sometimes it seems like everyone here, at one point or another, has tried Ecstasy, "X," "E," whatever you choose to call it, at least once. They've had the better part of two decades to do it in after all.

Ecstasy has been around Austin since it arrived from New York, via Dallas nightclub the Starck, in 1984. And despite everything -- the DEA's war on drugs, rampant scare stories, and obvious misuse, overuse, and outright abuse -- it's still very much here in the midst of the live music capital of the world, fueling all-night parties, love-ins, and clandestine husband-and-wife emotional therapy sessions.

Since the early Nineties, with the birth of Austin's electronica/dance, music/rave culture, the little love drug that could has become a multimillion dollar illegal industry for its shadowy manufacturers, who typically hail from south of the border, California, and, you guessed it, Amsterdam.

No cultural group has been more closely identified with Ecstasy, however, than the raver kids, those DJ-knob-twiddling wearers of monstrously baggy trousers who run fun-riot over assorted local venues on the weekends, dancing for hours on end to the sweaty, propulsive rhythms of house, jungle, drum-n-bass, speed garage, and trance.

Yet while ravers as a cultural group are indeed very active in the Texas Ecstasy community, they're hardly the only ones. It should go without saying that just being a raver doesn't automatically mean a person has ever tried Ecstasy, or ever plans to, or is anything other than a model citizen with a wardrobe full of preposterously oversized outerwear.

The spectrum of current and former Ecstasy users runs the gamut from the above-mentioned anonymous urban professional and his friends to nearly any type of person you might find on a Sixth Street Friday night, from fraternity and sorority types to punks and upscale clubgoers. Plenty of shiny happy people have crowded local 24-hour eateries after 2am for years now than can possibly be explained by two martinis and a quickie in a club restroom.

Naturally, it takes all types to fuel an ongoing movement like the country's Ecstasy boom, though the majority of users spoken to for this article tend to be college-educated, thoughtful, and well-spoken individuals. Despite its current standing as a federal Schedule I drug, which places it right alongside heroin and cocaine in terms of illegality, Ecstasy attracts the intellectual, creative types who find the idea of nodding off in a pool of their own vomit or jittering like a nic-fit reprobate all night somewhat off-putting. It's a party drug that's frequently shared by couples, alone and at home.

It's also the focus of an increasing amount of media attention these days. Recent studies have concluded that long- and short-term use of the drug may impede the brain's neural transmitters in charge of releasing serotonin and dopamine, chemicals responsible for memory, sleep patterns, and emotional highs and lows.

The story of Ecstasy and its arrival in Austin in the early Eighties is an epic tale of late-night debauchery, high-flying club life, and one very disgruntled Drug Enforcement Agency. It's also irrevocably tied to this city's vital electronic music scene, though as before, the tale of the tablet is less about dance-club culture than the emergence of a whole new strata of cultural subgenres. And as befits an age where the world appears to be on the cusp of a massive global technological revolution, Ecstasy advocates (along with their detractors) are becoming a noticeable presence on the Net.

Where did it all begin? Listen up. Class is in session.

Everything Starts With an 'E'

Germany, 1912: the Great War had yet to begin, Kaiser Wilhelm was still looking flash in his pointed hat and epaulet combo, and the little pharmaceutical company known as Merck was busily cranking out a new breed of psychotropic drugs, having previously given the world the one-two sucker punch of morphine and Dilaudid (and by extension, William S. Burroughs).

MDMA, the chemical abbreviation for Ecstasy, received patent number 274.350 one year later and then literally dropped off the drug map for a half-century. There persists to this day an intriguing rumor of its use during World War I as a battlefield stimulant. The story has it that German and American troops, cresting on a euphoric wave of MDMA, laid down their weapons for a little while and had a party. Wishful thinking, probably, but a nice story nonetheless.

During the mid-1960s, a California-based biochemistry Ph.D. by the name of Alexander Shulgin began investigating the long-dormant drug, eventually severing his ties with the University of California at Berkeley and his position at Dow Chemicals to study the drug and its possible medical applications full-time. Shulgin remains the first documented case of human MDMA use, which he nicknamed "Adam." Like his pharmacological forerunner Aldous Huxley, Shulgin was never content to test his theories on lab animals, instead using himself and later wife Anna, close friends, and research assistants. What Shulgin discovered during his 30-odd years studying the drug (he died in 1981 just as ecstacy began infiltrating the counterculture) was that MDMA had keen applications in the field of psychotherapy.

During the mid-Sixties and throughout the Seventies, more than a half-million supervised doses of MDMA were given to patients by their psychotherapists. In tightly controlled, clinical settings, physicians administered MDMA to a wide variety of patients. Whether their subjects were afflicted with depression, marital strife, post-traumatic stress disorder, terminal illness, or just general mental unhealth, doctors discovered that the drug broke down barriers to communication. By all accounts it appeared to be a wonder drug.

None other than than counterculture guru Timothy Leary sagely chimed in on the possibility of the drug's future misuse, saying "no one wants a Sixties situation to develop where sleazy characters hang around college dorms peddling pills they falsely call XTC to lazy thrill-seekers." Of course, that's exactly what eventually happened. Leary, never one to discount the benefit of unproven pharmaceuticals, married his wife Barbara in 1978 just days after their first shared "XTC" experience.

By the early Eighties, both the American political climate and the drug itself were undergoing massive changes. Jimmy Carter's folksy ineffectiveness gave way to the rose-tinted, right-wing fervor of the Reagan administration. Waiting in the wings, MDMA, commonly known by the street name Ecstasy by now, was poised to enter mainstream drug culture.

On the East Coast, in New York City and Boston, at such nightclubs as the Saint, Studio 54, and the Paradise Garage, gay men took to the Ecstasy that was being manufactured in city-wide bathtub operations in numbers unheard of since hippies discovered LSD. For them, it leveled emotional walls, created a deep, abiding sense of belonging, and allowed them to dance and party all night long. The previous drugs of choice, cocaine and poppers, paled in comparison. To top it all off, it was legal.

And then X found its way to Texas.

The E's of Texas Are Upon You

At 41, Kerry Jaggers is an Austin legend -- his name precedes him wherever he goes. Compactly built, with thinning, closely cropped hair and piercing blue eyes, dressed in a tight black Lycra T-shirt and dark trousers, he could pass for any other former clubgoer cautiously edging his way into middle age.

Calling Jaggers a "former" anything, though, is a mistake. The man who first DJed Austin's legendary punk and new wave Club Foot, then moved on to help establish countless other clubbing institutions -- among them Dallas' Starck Club, Houston's Rich's, Austin's Backstreet, and San Francisco's 1015 Folsom -- is still hard at work, taking monthly red-eye flights to assist at various club locales across the US and the UK. If you want to know when and how Ecstasy came to Austin, Jaggers is apparently the man to ask.

The high-profile club consultant probably knows more than anyone in Austin about the early days of the Ecstasy scene and what preceded it. Back in 1980, while spinning vinyl at Club Foot, he'd fly up to New York City on the weekends to hang out at a massive, planetarium-themed gay club known as the Saint (www.thesaint.com), one of several gay clubs in and around the Village that first danced aboard the Ecstasy bandwagon.

"The first time I went to the Saint," he says, "everybody was on Ecstasy. Pure powder. Everywhere.

"The thing about X back then was that it created this feeling that all my little fears of what anybody might think about me, or what I thought about them, the negative things -- all that was just gone. Everybody was there knowing that they would be accepted totally. At the time, it was legal, so there wasn't even any guilt associated with it, no fear. It was just something that everybody did, and it was a beautiful thing."

January, 1984: Jaggers had recently opened the gay club Rich's in Houston when he was offered a job DJing at the soon-to-open New York City club Private Eyes. The money was good, he would be close to his beloved Saint, and the gig seemed rife with possibility, so he packed up his records and flew to New York.

"Private Eyes was scheduled to open on Memorial Day 1984," he recalls. "That very day I got a call from my friend Grace Jones, who was appearing that night with Stevie Nicks at a new club in Dallas called the Starck, and she promptly flew me down to DJ."

Before Jaggers left New York, he managed to wangle a few ounces of Ecstasy to take with him to the as-yet-unecstatic state of Texas. The rest, as they say, is history.

"That's how the whole thing with the Starck began," boasts Jaggers. "Almost as an afterthought. I'm the man responsible for turning on Dallas."

From Dallas, it was just a sprint down the I-35 corridor to Austin, which was soon flooded with the drug. The progressive, party atmosphere of Austin in fall 1984 was well-suited to Ecstasy's euphoric high. The drug quickly swept through the already-knowledgeable gay community, and the club Halls at 404 Colorado St. -- currently home to Polly Esther's -- became Austin's E nexus. On Thursday nights, Halls hosted the mobile Club Iguana, and it was here, around the corner from Voltaire's Bookstore in the heart of Austin's current arts district, that the Austin Ecstasy scene exploded in one huge grinning bliss-out.

"You have to remember: There were no ravers in 1985," reminds Jaggers. "Most of them were in the act of being conceived at the time."

Who were all these people taking the oversized, speckled Ecstasy wafers?

"At Halls, it was trendy kids, frat rats, and students from UT," he says. "A lot of yuppies would come by in their BMWs. Halls had been intended as a gay club, but the gay community didn't take to it as fast as the owners had hoped, which is why Club Iguana -- this club within a club -- was started."

Whatever else it may have done, Austin's initial Ecstasy boom thoroughly warped any and all preconceived gender issues the drug's newfound audience may have held.

"Frat boys would go out with their girlfriends early in the night," recalls Jagger, "do some X, and then at the end of the night, they'd drop their girlfriends off at home, take another X, and come back to Club Iguana where they'd then either pick up or get picked up by a guy. I've heard that story more times than I can remember. Ecstasy brought down a lot of barriers between a lot of groups."

There are also the persistent apocryphal tales of legions of forethinking UT chemical engineering and MBA students reaping huge profits on their Jester Center dorm-bathtub X-manufacturing operations. There was so much legal Ecstasy around during the spring of 1985 that well-dressed student dealers were literally hawking their pills in the street outside Halls, undercutting each other's $12 price tags, and returning home each night more ecstatic than their customers, Dockers swollen with cash.

At this point, the Texas state capital might as well have changed its name from Austin to Super-Happy Fun Town, but already that atmosphere was doomed. Anyone with half a brain not split from ear to ear with one huge ridiculous smile could tell that anything this popular -- legal or not -- wouldn't be around much longer. They were right.

The Drug Enforcement Administration had been aware of Ecstasy since Dr. Shulgin's experiments took off in the early Seventies, but it wasn't until the drug spilled over into popular use that the agency began to take real notice. In July of 1984 the DEA opted to begin proceedings that would place the drug in the Schedule I category of the Controlled Substances Act, effectively making possession or use -- even within the medical community -- a felony.

Predictably, this didn't sit well with the yuppified street users and dealers, but more interestingly, the movement toward impending criminalization of the drug was challenged in open court by a raft of medical and psychiatric professionals, a move which caught the DEA completely off guard. The pleas from the medical community to keep the drug available to licensed therapists and medical professionals were many, impassioned, and very, very vocal.

Due in no small part to the open-air-market feel of Ecstasy dealing in Austin and other cities, however, the DEA rushed MDMA into Schedule I on July 1, 1985, using the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, which allowed for "emergency scheduling of any substance deemed to be a significant threat to the public."

The DEA issued a statement justifying the emergency scheduling, which mentioned the "open promotion of MDMA as a legal euphoriant through fliers, circulars, and promotional parties," and noted the almost certainly lowballed statement that "30,000 dosage units of MDMA are distributed in Dallas each month."

By all appearances, the party, here, there, and everywhere, was over.

It's Great When You're Straight ... Yeah!

Appearances can be deceiving, though. In the months after the drug went Schedule I, an unknown number of Texas-based manufacturers began tinkering with the molecular structure of MDMA in hopes of bypassing the law by inventing a new, albeit similar, chemical offshoot. The resulting hybrid, MDE, was tagged with the street name "Eve" and failed to take off.

Recreational users of Ecstasy found Eve's trippier, mellower high to be a bit of a letdown, and hardly worth the bother. Like the Edsel, Eve just wasn't what people were looking for at the time. What they were looking for -- MDMA, the real deal -- was in short supply. The collegians who had been Austin's chief source of street-level dealing had returned to their classes at UT once it became apparent any money they may have made from clandestine manufacturing would likely be used to hire pricey lawyers once the APD caught wind of their operations.

Halls and the Lizard Lounge dried up and eventually packed it in, though this was due as much to changing musical tastes in Austin nightlife as it was to the sudden lack of the party people's favorite Scooby Snack.

For five or so years, Ecstasy went more or less completely underground, and in some places outright vanished. Not just in Austin, but all across the country; from San Francisco, where it had gained a sizable toehold amidst the city's multigendered club scene, to New York and Boston, two other popular early-Eighties Ecstasy strongholds.

Madchester Rave On

There's no sobriety so great that a little druggy ingenuity can't overcome it, so during America's fallow Ecstasy years, the drug reappeared with a vengeance in England. Not that 1985-1990 were completely E-starved stateside, not by a long shot. Tablets and capsules continued to appear in the larger urban areas, including Austin, but the quality was rarely up to snuff. Besides, that old devil cocaine had made a startling comeback as the Eighties' drug du jour.

In 1988, England's so-called Summer of Love took flight, fueled in equal parts by the driving beats of acid house music and Ecstasy, dubbed "E" by the Brits. The emerging overseas rave community, weaned on the Detroit techno music of Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, and Juan Atkins, exploded with a shot heard 'round the world -- or at least in Europe -- ushering in a golden age of techno, house, acid, and their 1,001 permutations.

Record labels such as Alan McGee's legendary (and recently curtailed) Creation sprang up overnight to fuse the more traditional sounds of Northern Soul, bastardized Merseybeat, and psychedelia with the outright beat-barrage of electronic and DJ-inspired musical styles. The bands Primal Scream and My Bloody Valentine released two of the most important recordings of the past 20 years, Screamadelica and Loveless; both these and countless others made epic use of Ecstasy not only during the recording sessions (rumor has it), but also on a daily basis.

England's precociously asinine Top of the Pops was, for a time, rife with Ecstasy-inspired outfits such as the Shamen, whose jaunty "Ebeneezer Goode" was a cheekily obvious nod to the drug. Even international supergroups like New Order scored bonus points for their massive -- and massively publicized -- Ecstasy intake, as well as sneaking the line "E's for England" into their 1990 Royal-sanctioned World Cup anthem "World in Motion."

Kerry Jaggers cheerily claims full responsibility for that notoriously hedonistic band's longtime love affair with E. Back in the early Eighties, he hooked up New Order with their very first hits hours before their Club Foot show. Nearly a decade later, when they returned during a 1990 world tour, the band took a week off to soak in Austin's Ecstasy scene and relax on Lake Travis.

"They were walking around with sandwich bags full of cocaine and Ecstasy literally strapped onto their belts," recalls a mischievous Jaggers. "This is how we affected the English scene."

At one point in the early Nineties, the story goes, the British pub community circulated a sort of in-house pamphlet outlining methods pub owners could combat the increasing use of the drug by young people. So many Brits had taken to using the drug on the weekends that no one was going round to the pubs anymore, resulting in revenue losses unseen since WWII.

At the tail end of the Eighties, an Ecstasy hub of sorts arose in the Midlands city of Manchester, England, which in turn spawned the wildly popular "Madchester" scene, home to Shaun Ryder's pharmacologically oriented baggy-rockers the Happy Mondays (and later Black Grape), the Stone Roses, the Charlatans, the Farm, and the Inspiral Carpets. While Manchester had previously given the world Joy Division, the Smiths, and the Fall, absolutely nothing on the scale of these grinny, luvved-up, Fred Perry-wearing HappyTown Hooligans had ever been seen before.

Ecstasy ruled the roost then, and continues to this very day: This past April, the British drug czar noted that Ecstasy remains a veritable staple of nightlife across the entire United Kingdom, with an estimated 500,000 tablets and capsules changing hands every weekend.

Last Night a DJ Saved My Life

As the American rave scene took off in the early Nineties, youngish kids and the earlier, somewhat older generation of promoters, DJs, and clubgoers naturally gravitated back toward a drug that was still considered underground enough to be cutting-edge, and cool enough to be utterly without peer when it came to dancing all night beneath a storm of argon lasers amidst hundreds of like-minded individuals.

Attracted by the frenetic energy of the rave community, more and more kids began crossing that Fender Strat off their Yuletide wish lists and hurriedly scribbling in their urgent need for a pair of Technics 1200s turntables and a Roland 303. Grunge came and went, and the vacuum left by its ignominious passing was quickly filled to bursting with newcomers to the new Texas -- and American -- rave scene.

At 25, Levon Louis is a working model of what many kids in the Texas rave community are aiming for. Currently, he runs Space City Records (www.spacecityrecords.com), organizes some of Houston's most slamming raves (the last one, April 29th's Mystic Rhythms, played host to Philly's Dieselboy and Brit DJ Spike E, one of the UK's earliest proponents of rave and E culture), and along with Russian DJ Mir and Austin's JT, acts as one-third of the techno band LunaTex.

In July 1984, at the tender age of 10, Louis appeared in a Newsweek article on break dancing, bustin' moves with his pint-sized breaking crew. At 16, he began DJing around Houston, spinning at private parties, and working in and around a club scene he wasn't even old enough to legally be involved in. A couple of years later, Louis headed out to Nacogdoches' Stephen F. Austin State University, where he majored in electronic music and began throwing warehouse parties in the rehearsal hall of his reggae band Zion Lion.

After college, Louis moved to Dallas and says he immediately fell in love with that city's exploding rave community, working alongside the infamous Haysee Daze crew in Deep Ellum. In 1996, he returned to Houston, formed LunaTex, and began working seriously on getting the music to the masses while throwing major multimedia raves to help defray the cost of getting his own tracks out there.

"The first time I ever took Ecstasy was in 1993," he recalls. "I was given some by a friend at the first big rave I attended -- and by big I mean over 1,000 people -- in Dallas. I was frankly blown away by the effects, and though I've done it a couple of times since, I personally haven't taken any Ecstasy in several years.

"My focus has been on my music and in supporting the scene, finding and cultivating new artists. I haven't found myself needing that same feeling from that same pill, either, because whenever I'm in that rave environment, it all comes back. When you experience a thing like Ecstasy even once, you really don't need a drug to keep it going."

As one of Central Texas' top rave promoters, Louis has found himself in the thick of the emerging, mainstream-media-driven anti-rave climate, watching how Ecstasy -- for better or worse -- is impacting the scene, and what, if any, drawbacks there might be. Drug hysteria is fine and good for Dateline NBC and 60 Minutes II sweeps-week ratings-grabbers, but Louis says the reality of Texas' Ecstasy scene is a different matter entirely.

"The only damage I've seen is from people buying bad pills on the street," he says. "I see these kids walking around buying whatever they can get their hands on without knowing where it's coming from or who's selling it, and they're getting pills cut with crystal methamphetamine, ketamine, GHB, strychnine, cocaine -- whatever the supplier happens to have lying around. It's these impurities that get people into trouble and make people ill."

As for Ecstasy use outside the rave scene, Louis is convinced that said dance culture makes up only a fraction of the whole, a notion echoed many times not only by those interviewed for this story, but also by members of the APD, DEA, and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). Contrary to 60 Minutes II's recent interview with Detective Mike Stevens of the Orlando, Fla., Police Department, the warnings directed at parents about "rave drug paraphernalia" such as glow sticks, Vick's Vap-o-Rub, and painter's masks are as specious as saying someone with a pack of matches is an arsonist.

"You've got to understand that this drug isn't just being used by people at raves," says Louis. "From the professionals that I've been working with in my dealings with the record labels and from doing major events where I needed to procure funds from investors, many lawyers, investment brokers, high-level professionals, city officials, and just everybody I talk to outside of the rave community seems to have an understood appreciation of ecstacy.

"If they don't currently do it themselves, they have in the past, or if they do it themselves, then they just don't advertise the fact to their co-workers. But they all do it and they all know they do it. It's almost as though a lot of the urban professionals that I meet and deal with lead somewhat of a double life from the office to the weekend. And if that's what needs to happen, then so be it."

Nonstop Ecstatic Dancing

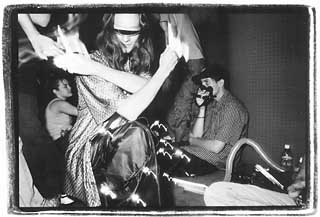

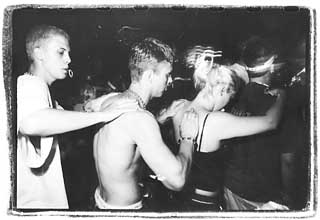

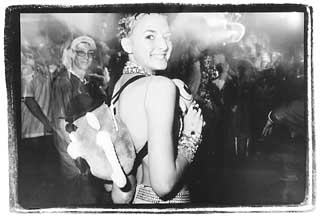

It's 2am on a recent Friday night. Do you know where the kids are? If not, follow the gargantuan beats haranguing the walls of the Austin Music Hall and you'll likely find them inside, dancing beneath a blanket of sternum-rattling bass or lounging outside on the Hall's open-air front deck, vacuum-packed in fresh teenage sweat like brightly hued sardines, dropping science, cigarettes, and the occasional tab of Ecstasy.

This, of course, is the new, improved millennial version of that popular teenage rite of passage that dates back as far as youth itself: getting fucked up and staying out all night. The only legitimately new spin on display, arguably, is the addition of the empathogenic Ecstasy; as far as youth movements go, even that has its older, trippier brethren in the psychedelic heyday of the late Sixties.

The parallels between the new century's rave culture and the original Woodstock generation are obvious. Both groups positioned themselves around a type of music that parents just don't understand. But when did they ever?

While the drug of choice has mutated from LSD to Ecstasy, the similarities between the two pharmaceuticals and their resulting subcultures are inescapable: both tend to bond people together (hence the term empath-ogen), and Ecstasy, while nowhere near the brain-baking power of LSD in terms of its propensity for hallucinations, does indeed have a minor reality-altering quality running alongside its methamphetamine high.

The music, the drugs, the clothes, the attitudes, the emphasis on cutting-edge technology and knotty doublespeak: It's as if the hippie guide book had been rewritten by William Gibson, tweaked by Bruce Sterling, and sent out as some crypto-funloving cyber-virus to kids hither and yon -- ILoveYou redux.

Inside the Music Hall, toward the front, a metal crash barrier is set up to hold back the throng. Behind it, slouching erect, is a presumably internationally famous DJ from New York/ San Francisco/London/somewhere doing what he does best, beatmatching two different 12-inch vinyl records, mixing them together, and winning hearts and minds at a furious pace that would make William MacNamara proud as punch.

Clustered around the artist at work, heads bobbing relentlessly, feet shuffling, all rapt gazes and fluttery hands, this vanguard of the new school is a sight to behold with its glowing tubes zipping all over the place and pouty empathogen grins. It's called liquid dancing, and the title is apt: Light sticks perched atop their fingers, the rave kids describe trippy little patterns in the air. It's hard not to find oneself unconsciously mimicking their movements, and realizing that the drugs aren't the only potential addictant around.

Walking the perimeter of the 1,200-plus attendees, awash in sound and light, is revelatory. As suspected, the median age tonight appears to be skewed toward the mid-teens. Only a dull smattering of hoary old twentysomethings have managed to elude their beds and make it out this evening, and they're bellied up to the bar in back, necking down $3.50 Shiner Bocks like it's a smart bar and they're moments away from going mano a mano with Regis.

Making his way through the crowd, an off-duty policeman works security. He doesn't appear particularly fazed by the excess of his current beat, nor does he seem to be very threatening to the ravers around him. He's in good-guy mode, and the kids barely register his presence as he slips past them and moves on through the throng.

Huddled in dark little camps abutting the throng is a flotilla of chill-outs: Kids all danced out line the walls, chatting, impossibly, amidst the sonic overload. Clearly, the lost art of lip reading is making a comeback. Cuddle-puddles dot the periphery. Ecstasy stimulates the tactile senses to the point where the whole concept of a back rub verges on the orgasmic. If kids have been told to just say no to sex, they've apparently got no qualms about just saying "hell yeah!" to their own private version of the next best thing: a tab of X and half-dozen like-minded peers massaging each other's backs and shoulders in what looks to be a supremely pleasurable, slackerized conga line.

Smiles abound, and not just on the blissed-out high-wire acts. As with any massive party, there's a palpable energy that comes from just being young and in the thick of the action. The trance occasionally swells into a juddering, stacatto break, and 1,000 hands stretch skyward en masse, glowsticks dotting the semi-darkness like Zippos at mom and dad's Seventies rock show.

The only difference is there are no beefy biker security guards to rough anybody up. Indeed, there's no apparent trouble of any sort, no evidence of alcohol- or drug-related mishaps anywhere. And with 1,200 or so kids in a loud, enclosed venue on a weekend night, that's pretty remarkable. Later, Levon Louis offers his take on the whole phenomenon.

"Raves are a very important part of what's happening in our society," he says. "Society as a whole is racing toward the future in areas of commerce and technology and the rave is a reflection in the arts of what's happening elsewhere. These multimedia displays of light, color, and sound are a clear reflection of the times we live in.

"I also think it's very important for the city and the state to recognize the importance of having a safe place for these young people to congregate peacefully and enjoy whatever forms of entertainment they might be enjoying, so long as they're not hurting anybody. There are almost never instances of violence at raves.

"I've worked at or attended over 300 raves in my life, and in all that time, I've seen only one fight, and even that was a case of a girl defending herself from an ex-boyfriend. These parties are giving kids who've made the choice -- right or wrong -- to do drugs in a place that's safe and supervised as opposed to cutting them loose on the freeways."

Dealing With It

Simon the ex-X-dealer has responded to my online query and is willing to be interviewed -- over the phone -- regarding his shady past. A face-to-face interview would of course be preferable, but apparently his current life outside the realm of illicit pharmaceuticals distribution is going swimmingly and he'd rather keep a lid on his previous line of work as much as possible.

The 29-year-old Dallas native admits spending "a couple of years" during the mid-Nineties selling Ecstasy in and around the burgeoning Austin rave scene. He's quick to point out that he also sold the drug to countless others ("cowboys, frats, you name it"), but his main focus was dealing to his friends in and around the local electronica scene. Asked to estimate how many tablets of Ecstasy he sold in his time dealing, he thinks for a long moment before hesitantly offering a figure in the 30,000-plus ballpark.

The television rule of drug-dealer thumb applies to Simon about as poorly as a cheap pair of Reebok trainers; for one thing, he's a well-spoken Aggie graduate who currently works for "a Fortune 500 company which I'm not going to name so please don't ask." Most dealers of Ecstasy appear to be users as well, and Simon is no exception, having been given his first hit at a Dallas rave in 1994.

"It made a huge impression on me," he says. "I immediately understood the aesthetic of what was going on around me. I wasn't much of a dancing person before, but I felt very comfortable in that rave environment. I could see that the music was very obviously tailored toward that state of mind, and any kind of latent homophobia that I may have had stashed away in my mind, that all sort of evaporated.

"There were all these drag queens there that first time I did Ecstasy and I just totally understood what they were about. It just created an amazing empathy in me toward others."

After that first time, Simon sought out the drug, and although the mid-Nineties were a notoriously dry time for Ecstasy in Texas, he made a connection and began dealing as a means of income. Regarding the continuing attraction of the drug in Austin, he notes that since Ecstasy is a relatively new drug, "you had the feeling that you were doing something that hadn't been done before.

"With drugs like acid or mushrooms, you're sort of tied to the past by the sense of history they engender," he explains. "What you were doing with Ecstasy was being part of the first generation of people to use this drug, recreationally, in this way. You were on the cusp of all these technologically amazing visual and musical events, and so you were literally on the forefront of American popular culture.

"It was a brand-new scene with an accompanying brand-new drug. It was underground, and it was very much like what the hippies must have felt in the mid-Sixties with LSD. The cops didn't even know about it yet."

By anyone's standard, dealing illegal drugs is right up there on the stressful jobs scale, so after a few years, Simon decided to quit while he was still ahead.

"Eventually, I had too many ethics to continue drug dealing," he says. "If someone stiffs you, you can't just call the police like you would in the real world. You have to enforce your own rules, and that can cause problems.

"But I took a lot of care in the curatory aspects of what I was doing. I made sure that what I was selling was real. I really tried to make sure that this stuff ended up in a safe, useful form. I took care to inform people of guidelines for use, and tried to make sure that the people I sold to were not getting sloppy with this drug.

"The problem" he adds, "is that there is the potential for abuse with any drug, and there are real dangers with Ecstasy. It's typically not the kind of thing you want to do every single weekend. There are those people that do, of course, but typically that's not the case.

"Dealing Ecstasy, I felt that I was helping people have an experience that, hopefully, will have an enlightening aspect to it. I can give some very forthright recommendations about doing this drug. Which is nice, because so much of the 'War on Drugs' rhetoric is so transparent. It's such bullshit. And, of course, once the government gets this reputation of dispersing bullshit to young people, it becomes very easy to blow off anything 'they' say."

Fool's Gold

Detective Michael Burns is a 15-year veteran of the Austin Police Department, with 10 years of narcotics work. Deferring to his precarious position as an undercover officer, we'll dispense with the physical details. Suffice it to say, he's got a quick smile, a rapid-fire delivery when he speaks, and a solid family life. A stack of High Times magazines and a poster depicting various images of LSD blotters vie for space in his small Twin Towers office. Stern and scowling Joe Friday he's not. Asked how the war on drugs is coming along, Detective Burns shakes his head. "We're not winning it," he admits. "We're just taking the top off things."

As far as Austin's Ecstasy situation, Burns says he doesn't think there's a boom under way, believing instead that much of what passes for MDMA on the street is actually over-the-counter cold remedy ephedrine, retabbed and packaged as the real deal. Detective Burns also notes the increasing popularity of other so-called club drugs such as Ketamine and the notoriously dangerous animal tranquilizer GHB, which took off in Britain years ago and is only now making inroads in the States.

Since the question on everybody's lips these days is if Ecstasy is as outright dangerous as the prime-time news magazines and their sweeps-week horror stories would suggest, Detective Burns naturally expects the query. Users say no way, but Burns' answer to the question, although hardly unequivocal, is notable for its restraint.

"I don't really know of any actual overdoses on Ecstasy where anybody's ever died from actual Ecstasy," he says. "What they die from is overheating, exhaustion, and dehydration.

"What Ecstasy does to your system is very similar to speed -- it heightens users' senses, makes them feel wide-awake, vibrant, and able to do more and have more energy. The downside of it is that it also raises the body's temperature. Normally, when your body gets tired, you start to cramp or get exhausted. Under the effects of Ecstasy, you don't notice that and you keep going and continue to elevate your temperature.

"After about four or five hours of this, the person reaches an overheated position, they're dehydrated, and they pass out. Their friends think they partied too hard and just let them lay there. And then five or six hours later they die."

The APD has long been a presence on Sixth Street, but Detective Burns says interdiction efforts are stymied by the incestuous nature of clublife.

"It's like a news line down there," he explains. "If you're at one club and do a deal and somebody is taken down or arrested, all the clubs know about it within 30 minutes. So that makes it real hard to work it logistically. Plus, if I'm not going to bust you right that second, I have to identify you, and when you've got anywhere from 80,000-100,000 people coming and going every weekend on Sixth Street, that's a huge task in itself."

Burns still considers crack cocaine to be Austin's No. 1 drug problem, far outweighing the marginally lesser evil of Ecstasy. Because users of drugs such as crack are more likely to commit violent crimes and robberies to score the money to feed their high, the APD continues to pour their resources into street-level interdiction and arrests. Although the media stories that were so prevalent in the late Eighties have more or less subsided, crack in particular remains a major cultural and economic threat, especially in East Austin.

Since it's the new kid on the felonious pharmaceutical block, relatively little is known about the long-term affects of Ecstasy on human physiology. A report released in February by the National Institute on Drug Abuse says, "MDMA harms neurons that release serotonin, a brain chemical thought to play an important role in regulating memory and other functions."

The NIDA/Johns Hopkins University-sponsored study utilized a technique known as positron emission tomography to effectively map the brains of 14 MDMA users who had not used any psychoactive drug, including Ecstasy, for at least three weeks. A similar grouping of people who had never taken the drug at all was used as a control, and the brain scans from the two groups were compared.

The results clearly showed depleted serotonin production in the MDMA group, though exactly what the functional consequences of MDMA use might be are still open to debate. The facts, or lack thereof, indicate more research is needed before the true neurotoxicological dangers of Ecstasy can be explored further. Of course, that doesn't mean that today's Ecstasy users aren't dumbing themselves down for a future as baggy halfwits. Or vice versa. Information is at a premium.

Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior

Saddled with the unwieldy title of Parke-Davis Centennial Professor of Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Texas at Austin, Dr. Carl Erickson, author of the book Drugs, the Brain, and Behavior agrees that more research into the dangers of Ecstasy is of paramount importance.

"Part of the problem is that the kids who are using rave drugs like Ecstasy are five years ahead of the scientists," he notes. "Scientists can't pick up on how these drugs are working quickly -- they have to run controlled experiments over a long period of time, and that's only after they write the grant and get the money, which usually takes about two years.

"That's why this is so frustrating for us. We never know the definitive answer for anybody who wants to know more detail about these drugs. All we can do is guess."

To Erickson, Ecstasy's addictive potential is more problematic. Because the drug is an offshoot of methamphetamine, about which much is known, Erickson believes that although it may not cause addiction in everyone, there is the potential "that it's capable of doing that in individuals that are susceptible to addiction."

Though none of the users interviewed by the Chronicle expressed concern or belief in Ecstasy's addictive properties, that doesn't necessarily mean that they're not there. Cause for alarm?

"I think that the more kids who use the drug," says Erickson, "the more will become dependent on it. It does affect mood, it does affect judgment, and therefore it affects driving skills. As with any amphetamine, or with cocaine, you have the chance of raising blood pressure, which could result in a stroke or increase the possibility of seizure activity in pre-epileptic individuals.

"As far as the long-term side effects, one of the things that scientists kind of believe is that MDMA will likely destroy brain cells with continued use. The reason I say 'likely' is because this has been shown to be the case in animals, but it's never been shown that this occurs in humans that I'm aware of. And I don't even know if you can extrapolate that information to humans."

Clearly, there are legitimate concerns relating to the long-term health issues of Ecstasy users, and more and more reports are coming in of young people collapsing at raves and parties from dehydration and massive overheating brought on by nonstop, Ecstasy-fueled dancing.

Some of this unwanted attention is warranted: When kids start to die, no matter how baggy their wardrobe, people -- parents and public officials vying for attention this election year, especially -- pay attention. On the other hand, it should be noted that no single instance of anyone dying from the toxicological effects of ecstacy ingestion have been recorded.

Protection

One group working to combat the dangers of Ecstasy use is the online resource DanceSafe (www.dancesafe.org), which was recently featured on 60 Minutes II's Ecstasy exposé and praised by several Ecstasy users mentioned in this article.

Founded as "a national, nonprofit harm reduction organization promoting health and safety within the rave and nightclub community," DanceSafe's wealth of online information could conceivably be a marginally safer jumping-off point for the millions of Ecstasy-mad kids who can't find similar safety information elsewhere.

This sort of self-policing of the rave scene is a fairly recent development in the U.S., but has been going on in Europe for years, with Web sites such as the late Nicholas Saunders' groundbreaking www.Ecstasy.org leading the way. Saunders, a middle-aged Brit who discovered the drug in the mid-Eighties, penned the seminal E is for Ecstasy in 1993 as a way to share his experiences with others and offer what little scientific information he could unearth at that point.

Like Ecstasy.org, DanceSafe has rounded up as much information as it could find and offers it to the drug's potential users free of charge. For those interested, DanceSafe clearly and accurately refutes much of the recent horror stories attributed to the drug, such as 60 Minutes II's apparently unfounded (not to mention journalistically suspect) claim that over 1,100 people have died from Ecstasy in the United States in the past few years.

According to DanceSafe, "the figure of 1,100 emergency-room visits due to MDMA comes from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) system. DAWN compiles statistics of emergency-room visits where a particular drug happens to be mentioned by the patient or one of their friends, regardless of whether the drug caused the emergency. Also, blood tests are not required, so it's impossible [to determine] if the patient consumed real Ecstasy or DXM, a common adulterant on the Ecstasy market that is much more likely to cause medical emergencies that real MDMA."

DanceSafe's explanation rings true. In the course of researching this article, the Chronicle contacted both Brackenridge and St. David's records departments seeking any information they had regarding Ecstasy-caused ER admissions. At both hospitals, the answer to my question -- after a hesitant "you want admissions records for what?" -- was that neither facility keeps records on specific drugs.

Apparently, in a typical ER, unless the APD is officially present at the time of the patient's admission, "drug overdose" is what goes on his or her chart. That information, without regard to specificity, is then passed on to the state, which in turn presents its statistical findings in a breakdown of drug crimes by city, county, and so on. Currently, Ecstasy has not yet been added to Texas' statistical information, still falling under the rubric "other."

Snapshots From the Front

Boston, April 29, 2000: Federal Agents seize 172,000 Ecstasy tablets with an estimated street value of $4.5 million, the largest seizure of the drug ever in New England. Two men, Israeli nationals Yaniv Yona and Ereza Abutbul, both 23, are arrested by U.S. Customs agents as they attempt to receive delivery of FedEx packages containing the drug.

Phoenix, February 24, 2000: Sammy "The Bull" Gravano -- onetime mob assassin and the man who snitched out "Teflon Don" John Gotti -- is arrested at his home and charged with controlling the distribution of Ecstasy in Phoenix and surrounding areas. Gravano had dropped out of the Federal Witness Protection Program two years earlier, saying he was sick of always looking over his shoulder for "some kid" hoping to "make a name for himself by taking me out."

New York City, February 23, 2000: The DEA breaks up a Tel Aviv-run Ecstasy ring in the Big Apple (novelly employing bearded orthodox Jews as mules) after an eight-month undercover operation. More than one million Ecstasy tablets headed for the U.S. are intercepted. According to sources, "the pills were produced in the Netherlands at a cost of 50 cents to $1 per pill and eventually were sold in New York, particularly at so-called rave clubs, for $25 to $50 each."

Miami. Houston. Los Angeles. There are more Ecstasy busts than ever before, which might be seen as an indication of the drug's increasing inroads into American popular culture. It could also be the result of more media attention to the drug, hence more pressure on federal and state agencies to make more arrests. It might even be seen as a result of the fiery politics of this election year; nobody wants to appear soft on drugs, at least not anyone hoping to win any sort of political mandate these days.

Hollywood is even getting into the act, with a pair of Ecstasy-themed films -- Greg Harrison's Groove and Brit Justin Harrison's Human Traffic -- due out later this summer, a sure sign that the drug has broadsided mainstream pop culture in heretofore unseen ways. (Doug Liman's Go doesn't really count, since that film's Ecstasy use was less a plot point than a Hitchcockian maguffin.) And maybe you've even caught the recent breath-mints TV spot featuring a comely clubgoer popping an enticing little blue pill? That ain't no Tic-Tac, baby.

The question remains: Is Ecstasy, the little pill with the smiley-face sensuality, threatening to sour the hearts and minds of America's youth, not to mention the casual weekend yuppie users who've taken to it like their early-Eighties frat-boy forerunners? Or is it just another negligible facet of Austin's intellectually hedonistic lifestyle?

"In Austin, most [people who use Ecstasy] are going to be 18-25 years of age, college-educated kids, and they're using it as a recreational drug," Detective Burns says. "Part of it is experimentation, rebellion against authority, cutting loose and so on, but when you buy it at a club, the dealer isn't going to tell you to make sure and drink plenty of fluids and don't operate any heavy machinery, you know?"

Levon Louis agrees, at least in spirit:

"The real problem I see is that these drugs get in the hands of kids who are not old enough to take responsibility for their actions," he says. "They're not recognized as adults by the state and they're not recognized as adults in my eyes, either. If you're 16 years old, then you don't need to be doing Ecstasy, and that's the bottom line.

"If you've made it through high school and you're in college or supporting yourself, making your own decisions in life and not living at your mom and dad's house anymore, then you can take responsibility for what you do to your brain and body. But until you're all grown up, you really should be cautious and try to avoid getting yourself into a situation where you could cause yourself trouble. There's a lot of bad medicine out there.

"Bottom line? Be careful what you do." ![]()