The Nine Lives of Ol' Possum

And Along Came (George) Jones

By Jerry Renshaw, Fri., Oct. 22, 1999

Near the door of Ray Hennig's Heart of Texas Music on South Lamar, you'll find a framed photo of Hennig shaking hands with George Jones and band. The crew had just purchased a complement of Fender guitars and Fender Twin amplifiers; Jones' geometrically perfect flattop is as stiff as a toothbrush, bristling straight up from his head about three inches. Hennig and Jones are beaming for the camera, the music-store proprietor proud to be shaking the hand of a country legend and the legend looking a little glassy-eyed and dazed. "I got on board with George Jones about l965 or so, about the time of "She Thinks I Still Care,'" recalls Hennig. "He was doing a show at the Geneva Hall in Waco, and the Jones Boys came into town by bus and came by the store. George came by the store later that evening with his manager. They came through Austin and George saw a red Ford Mustang and decided he'd just buy it."

Jot down a short list of post-WWII male country superstars: Hank Williams, Lefty Frizzell, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson. There's maybe half a dozen more, at least, but Jones makes the list every time. Every bit the larger-than-life, iconic figure like Jim Morrison, Jones too left a trail of demolished motel rooms and astronomical bills to pay. And like Pete Townshend and later Kurt Cobain, he smashed guitars onstage. Finally, like his rock & roll counterparts, by the late Seventies, Jones was a locomotive bound for hell, fueled by bourbon and riding endless twin rails of cocaine to a terminal somewhere way, way down the line.

Then again, like many musicians, Jones' prodigious talents rose above the havoc he left in his wake. A small sampling of his prodigious recorded output ranges from sublimely goofy numbers such as "Love Bug" or "I'm a People" ("If I was a monkey a-workin' for a livin', I'd be a-gittin' instead of a-givin', hangin' by my tail, waitin' for the dinner bail") to conventional honky-tonk shuffles such as "Tarnished Angel" or "Empty Bottle, Broken Heart" to achingly sad and beautiful ballads like "A Good Year for the Roses" or "The Grand Tour." Jones' amazing voice shines through it all.

Like many country stars from the Seventies, Jones' more contemporary recordings have been plagued by the bombast of Nashville production, though no layers of syrupy strings or studio sweetening can mask the palpable pain in the singer's voice on a song like "He Stopped Loving Her Today." One of Jones' early Eighties hits, "The One I Loved Back Then (the Corvette Song)," was all but a novelty ("she was hotter than a $2 pistol, the fastest thing around"), but anyone who fancies themselves a singer should take a stab at it: Jones' rendition spans all 17 or so of his octaves.

Nick Tosches' comprehensive if occasionally pedantic tome, Country: The Twisted Roots of Rock and Roll, goes into great detail about the tragic lives of many a country star like Hank Williams and Spade Cooley, people who grew up dirt-poor and desperate, only to find themselves awash in money later in life. Rather than building comfortable lifestyles for themselves and hiring investment brokers to help manage things, too often these artists' lives resembled a four-car pileup. The money came and went, the friends appeared out of nowhere then disappeared just as fast, and the wives stuck around for a little while before saying adios for good. Jones' life fits the description, or rather helped establish it.

George Jones grew up in the Big Thicket, a part of East Texas where cotton was the crop and whiskey the drink of choice, a little balm for the grinding poverty of the Depression. In the Thirties, malaria overran the swampy, snake-infested country; Jones lost his oldest sister to the disease five years before his birth, which drove his father to the bottle. After the family moved to Beaumont, Jones got his first guitar and began learning to play.

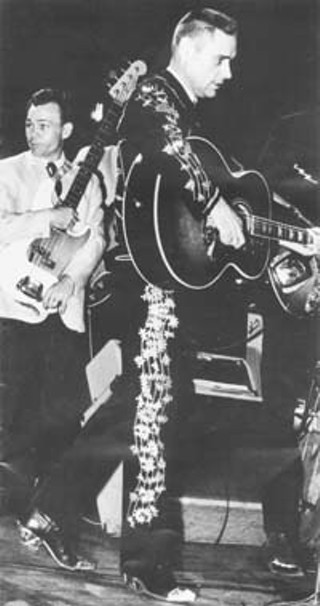

A well-known photo shows Jones carrying a guitar on the streets of Beaumont, a look of purpose on his young, handsome face. Before long, he was playing for audiences and money, a turn that eventually led him to various East Texas honky-tonks that make South Austin's rougher joints look as threatening as 1910 Iowa garden club meetings. Danger hung in the air of such dives, heavy as the smells of stale beer and piss, and at age 20, a slash across the belly with a straight razor nearly cost the young Possum his life; the origin of Jones' famous nickname's is unclear, but it has dogged him nearly as long as "No-Show Jones."

After various day jobs, a brief marriage, and a stint in the U.S. Marine Corps, Jones caught the interest of now-legendary country label Starday Records; the "Star" came from Jack Starnes, Lefty Frizzell's manager, the "Day" was Pappy Dailey, who later became Jones' manager. His first few records found Jones emulating his idols -- Williams, Frizzell, Bill Monroe and Roy Acuff -- until in 1955, he found his true voice and broke though with "Why Baby Why," still a Jones staple today, and began to tour in East Texas and Louisiana.

With Elvis at the fore, however, rock & roll began to overtake country music's popularity by the end of '55. Plenty of country stars put out albums that sounded a lot closer to rockabilly; early sides by Red Sovine, Johnny Horton, the Maddox Brothers and Rose, Conway Twitty, and plenty of others show more pure abandon than the staid Grand Ol' Opry formula. Buck Owens recorded rock & roll under a pseudonym to avoid the ire of the Bakersfield establishment. So, too, tried Jones, who at his manager's urging, adopted the nom de rock "Thumper" Jones and cut "How Come It, Dadgummit" and "Maybe Little Baby." The results are as compelling and primitive as any rockabilly from the era, with Jones supplying over-the-top inflections behind his vocals.

"I did some rock, had fun with it, but it didn't touch my heart," says Jones in the liner notes of the excellent 2-CD collection, Cup of Loneliness. "I was always looking forward to the next song so I could get back to a ballad."

Either way, such tunes certainly pique one's curiosity as to what might have been if he'd pursued rockabilly. The hits that followed in the Fifties, "What Am I Worth," "Seasons of My Heart," and "Don't Stop The Music" to name a small handful, helped define the country ballad style that became Jones' hallmark and one of the most imitated styles in all country music. Starday, meanwhile, merged with Mercury, a business move that would eventually dissolve with acrimony on all sides.

As his popularity increased, Jones' idea of fun became more and more extreme and irresponsible. Pappy Daily bailed him out of jail once and landed him a $2,500 gig in Houston. Jones played the gig, threw a party, and got drunk; word filtered back to Daily that Jones had flushed the remainder of the money down the toilet. Daily confronted the singer about the incident, saying, "Golly, George, I get you out of jail, get you a date, give you front money and buy you new stage wear, and you go and flush $2,500 down the toilet!"

"That's a goddamn lie," replied Jones. "It wasn't but $1,200 [I flushed]."

Jones' autobiography, I Lived to Tell It All, recounts in painfully stiff prose the one-way ticket to Hell his life became. All the stories are there, including the time Jones rode his lawn mower to the liquor store after being denied the car keys. There's the story of his first tour bus, "The Gas Chamber," with an interior consisting of several metal folding chairs, a couple of cots, and air conditioning, courtesy of a floor ventilated by six shots from Jones' .38 revolver. The vehicle eventually rolled down an embankment with the band inside.

Then there's the one about Jones, Johnny Cash, and Merle Kilgore teaming up to wreck a motel room, as well as another one about Cash letting a flock of live chickens loose in a hotel (shades of Keith Moon). In one tale, the Jones Boys, with Johnny Paycheck in tow, traveled from Milwaukee to Vidor, Texas, by car, with the boss insisting that someone trail the band on a moped at all time. The trip took four days, with Paycheck crashing the two-wheeler.

Thus Jones' life evolved into an endless stream of fistfights, parties, one-night stands, and hangovers in between concerts. Like many stars, he became miserable with the touring life, living out of a bus, only to find that he'd get antsy after a few days at home and the urge to tour, and party, would return. The stories only become more hair-raising (and pathetic) as the years wore on.

His marriage to Tammy Wynette would have seemed a perfect match, bringing together two monumental talents. Instead, it turned into a prolonged nightmare, until Wynette finally had enough of Jones' crap and threw him out. Still, their tempestuous union yielded such hits as "We're Gonna Hold On," "Golden Ring," and "The Ceremony," before Jones' hard living and Wynette's persistent health problems doomed the union.

Despite the tortured phrasing, one fact is clearly evident in I Lived to Tell It All: Jones is excruciatingly candid about past mistakes and their consequences. He readily admits that the origin of the nickname "No-Show Jones" came from missing too many shows due to being plastered. Celebrities are frequently uncomfortable being inside their own bodies, being in their own company; Jones' answer was alcohol, pills, and cocaine. To fight the depression and shame of drinking, he'd drink more. To find the energy to go on, he'd put a gram of cocaine up his nose.

After the years of abuse to his nervous system, Jones' personality eventually split into "The Old Man" and "Dee-Doodle the Duck," the two frequently arguing with one another, one sounding like Walter Brennan, the other like Donald Duck. Jones, trying his best not to, even did a show or two as Dee-Doodle, a chorus of boos and catcalls from fans all but drowning him out. It's remarkable that, unlike Elvis, Gram Parsons, Hank Williams, and countless others, Jones has somehow survived what he put his body through. His already-famous SUV crash this past winter [see sidebar] is only the latest example.

"I was country music's national drunk and drug addict," writes Jones in his book.

Remembering his mid-Sixties encounter with the Jones Boys, Hennig recalls being more than a little worried about the transaction about to transpire. "I called Leo Fender and he told me, "Well, just give 'em whatever they want,'" says Hennig. "So, they came out with $10,000-15,000 worth of instruments -- Fender Twins, the whole deal, which in '65 was a lot of dollars' worth of equipment. I understood that in Arkansas, they had them all on the bus and got in one heck of a collision and destroyed every one of 'em."

Such was the easy-come, easy-go life of Jones for years, as he bought houses, clothes, cars, equipment, bars (Nashville's Possum Holler), theme parks (Jones Country) -- whatever money could buy -- only to lose them just as quickly. Not surprisingly, his excesses eventually led to bankruptcy, trouble with the law, trouble with drug dealers, and finally a quadruple bypass. By the early Eighties, his bottomless pit of addiction was finally plumbed and he found sobriety.

Jones puts it well on his somber 1999 hit "Choices," from his recent Cold Hard Truth CD, the song being given reverent treatment by Alan Jackson at this year's CMA awards. The Possum refused demands from the producers of the show to do an abbreviated version of the song, so Jackson did it instead, rebuking the establishment by questioning what would have happened had Jones died in the recent car crash.

Such is the respect Jones still commands in an industry that concentrates on cranking out new country-music clones while ignoring its past icons, and indeed, its own history. Giants like Merle Haggard, Waylon Jennings, Johnny Cash, and Loretta Lynn can't even get country airplay in 1999; the fact that Jones can be honored in such a public way (and not as a dusty relic of country's past) speaks volumes.

Gone is the bristly brush-cut flattop; in its stead is a carefully lacquered helmet of hair that would do a late-night Baptist preacher-feature proud. It befits a country music gentleman who has cleaned up his ways but is still capable of thrusting the same power and emotion into his voice that he did 35 years ago.

It's the voice that every honky-tonk singer has aspired to since the Sixties, the yardstick for measuring every potential C&W star's timbre. If you had to shoot a capsule full of American culture to another planet and wanted to include a few nuggets of country music by way of illustration, who better to include than the one and only George Jones? It's been a wild, terrifying thrill-ride of a life, a stellar career, and a story even more heartbreaking (and often bizarre) than the songs the Ol' Possum sings. ![]()

George Jones plays Stubb's Friday, October 22.