Got My Mojo Workin'

Paul Oscher used to blow harps for Muddy Waters

By Tim Stegall, Fri., June 27, 2014

Thursday night at C-Boy's Heart & Soul, and Steve Wertheimer's southside juke joint is drenched in true blues. Dim lights, vintage soul posters, foil streamers, and a threepiece rhythm section. A dignified hepcat in black is up front playing, his white hair slicked back behind wraparound shades perching out above a trimmed white beard.

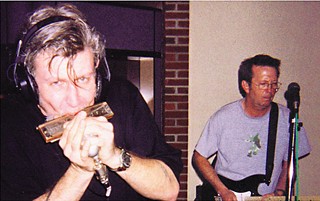

He's seated, pulling jagged electric guitar lines from an old Harmony hollow-body. Then thick-toned Little Walter lines from a rack-mounted harmonica. Eventually, he moves to an electronic keyboard and coaxes blues piano legend Otis Spann's warm, rolling cadences. Sometimes, he might play all three at once.

He dusts his rhythm section often, able as they are. His blues run raw and deep, from Chicago's South Side to the Mississippi Delta. His repertoire's pure: many Muddy Waters songs, Robert Johnson's "32-20 Blues," Big Bill Broonzy and Mississippi John Hurt numbers, Freddie King's shuffling "Hide Away."

Holdovers from a previous residency at a now-closed barbecue joint in Manchaca fill the club. There are tipsy young nubiles to chat up at break. Locals like Greg Izor and harp hero Walter Daniels watch and learn. Some may dare to join him onstage.

Hugh Laurie, Fox's wonky Dr. House, is in the building. The British actor doubles as a crack blues pianist. He's in Austin to play his own show that Friday at the Paramount Theatre. Tonight, Laurie's just another punter in awe of that hepcat clad in black, squeezing real blues out of three instruments.

The hepcat is named Paul Oscher. In 1967, at 17, this white kid from Brooklyn desegregated the Muddy Waters Band.

Mannish Boy

Oscher puffs Marlboros on the Sam's BBQ patio as he sorts through how he came to aid Muddy.

"Through Jimmy Mae," he says. "He knew the guys in Muddy's band."

Paul Oscher played harp for Mae in the mid-Sixties. The two also had a duo act playing tracks like Slim Harpo's "Baby Scratch My Back" in black clubs around New York.

"They'd have these little shows – an emcee, a vocal group, female vocalists, maybe even a comedian," Oscher recalls. "They would call us Salt & Pepper. There were a lot of places in the area where people had Southern roots, and we were getting over. Jimmy was from the South."

Oscher came backstage with Mae at a blues night at Harlem's Apollo Theater in 1966, one showcasing Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker, Lightnin' Hopkins, T-Bone Walker, Bobby "Blue" Bland, and Muddy Waters. Waters had heard Oscher play and was impressed. The Chicago great called Salt & Pepper back to the Theresa Hotel. "We drank and shot dice," says Oscher. "And Muddy took my number."

Six months later, Waters returned to New York City on tour with no harpist. Big Walter Horton was supposed to show up but didn't. Waters' guitarist Luther "Georgia Boy, Snake" Johnson called Oscher to the gig. "I played two numbers," he remembers. "'Blow Wind Blow' and 'Baby, Please Don't Go.' When Muddy got off the bandstand, he said, 'Can you travel?' I said, 'You're damned right!'"

Oscher found himself one day later in a green Volkswagen bus seated opposite drummer S.P. Leary and Otis Spann, history's greatest blues pianist, as well as Spann's girlfriend Lucille, and Waters' driver Bo. Muddy Waters rode one car ahead in a station wagon. Half a century later, Oscher's memory is crystal clear.

"Spann says to Lucille: 'Baby, gimme my shit.' Lucille reaches in her bra and hands him a .22 automatic. He checks it, puts it in his pocket. Then he says to S.P.: 'Gimme a taste.' S.P. gets a bottle of Gordon's Gin, he hands it to Spann. Spann takes a drink, Lucille takes a drink, I take a drink, S.P. takes a drink. Then we hand it up to Bo, and Bo takes a long swallow. Then he says, 'I see the moon, and the moon sees me! I see God, and God sees me!' I said, 'Goddamnit! I'm in it, now! This is it!'"

The Keys to the Highway

Muddy had one saying: "You've got something good, keep it in your pocket."

At the time that Oscher was coming up, nobody showed anybody how to play anything. "You'd ask a guitar player, 'How'd you do that, man?' He'd say, 'Man, I don't know. I just play like how I feel.'

"You had to watch really close. And if a guy saw you watching too hard, he'd turn his back. James Cotton told me he asked Little Walter how he got that warble sound on the harmonica, whether he was shaking his harp this way, or moving his head. How was he doing it? Walter said: 'That's easy, man!' And he turned his back on Cotton so he couldn't see it!"

Paul Oscher's first blues lesson came courtesy of a black co-worker at a supermarket he'd make deliveries for as a child. The then-12-year-old was practicing Hohner instruction pamphlet fare like "Red River Valley" on a Marine Band harmonica his uncle gave him. The co-worker demanded to "see that whistle you got!"

"He takes that harp and goes: [cups hands, vocally mimics a blues lick]. Man, I never heard a sound come out of a harmonica that sounded like that!"

Then followed a three-year immersion into the art form. He'd play along with every blues record he could find, weighing down his phonograph's tonearm with nickels.

"It messes up all your records, but that would slow it down enough to where you could learn the licks."

One night, at 15, he walked past a black club, the Night Cap Lounge, while practicing his harp. His playing caught the ear of the doorman, Smilin' Pretty Eddie, who brought Oscher in and handed him a mic. The crowd went nuts for the Little Walter covers.

"The women looked like the Supremes, and the men looked like Ike Turner with the processed hair, and there were Cadillacs outside the joint. I walk off the bandstand towards the shake dancer. I'm walking to the bathroom, and she's putting her pasties on. One breast is bare, and the other breast? She's working on that. She looks up at me through those false eyelashes, bats them at me, and says, 'Hey, baby!' I said, 'Man, that's my life! I like everything about this!'"

Two years later, Oscher climbed aboard Muddy Waters' green VW van. Soon after, he was the one glaring down from a photograph advertisement for Hohner, a monumental harmonica manufacturer, simply for daring to fill the shoes of classic Waters harpists such as Little Walter Jacobs and James Cotton. His tenure would see the band go from processed pompadours and sharkskin suits to naturals and Nehru jackets. Between road dates, he played on albums like After the Rain and lived in Waters' Chicago home, alongside Bo, Spann, and Lucille. "There was a piano in the middle room, too. So, Spann would come over and play," he remembers.

Sometimes, Spann would push a Farfisa organ into the alley across the street, jamming with other musicians coming by with bottles from the liquor store around the corner. "He showed me how to play that delayed time, where to come in and out with the harp. You're never really directly on the beat, if you're playing the blues right. You're just a little bit off and the music has to expand and contract. You do that, it's like a preacher preaching. You listen to the cadences and it opens up and closes up. There's a lot of suspense.

"But I never really copied any of Spann's licks. When people hear me play, they think it's like Otis Spann. But it's really his phrasing and timing. That's the key to the blues I play."

I Feel Like Going Home

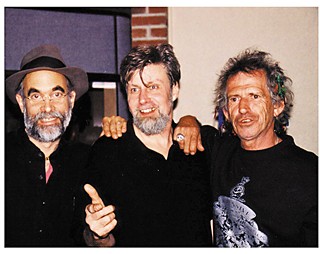

Oscher spent four years wailing around the world alongside Muddy Waters' right shoulder. He had priceless experiences, like frustrating his hero Little Walter at three card monte in Waters' living room, but soon he moved on, playing for a time as "Brooklyn Slim." He made records for himself and with others – Mos Def, Eric Clapton, Levon Helm, Keith Richards, and Waters' son Big Bill Morganfield – and won W.C. Handy awards for blues playing. He left music and held a straight job, which he refuses to talk about. The image of that shake dancer's bare breast and "Hey, baby" greeting surely brought him back.

Following his recent divorce from Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Suzan-Lori Parks, who based her play Topdog/Underdog on his youthful experiences playing three card monte, Oscher relocated in from Venice Beach, Calif., to cozy, little Manchaca.

The day Oscher's moving van arrived in Manchaca, a Volkswagen pulled up. The window rolled down, and a familiar face grinned at him. It was his neighbor, James Cotton. The 78-year-old fellow Muddy Waters vet's been living quietly in Manchaca for years, venturing out to play shows around the world.

Cotton and his wife/manager Jacklyn took Oscher to eat at a favored nearby eatery, Railroad Bar-B-Que. (See "Chairman of the Board," April 25.) Looking around, he had an idea to start some music there. He found an ad for a stage for sale on Craigslist and put it in at Railroad.

"It was just a place for me to hang out, get my chops together," he says. "Not no big show or nothing. Just tell stories and stuff, y'know?"

Oscher started playing Tuesdays at Railroad, growing his residency organically. Cotton usually sat in the back if in town, smiling approvingly at the goings-on, whispering greetings to admirers. He survived a throat cancer battle in the Nineties.

After a while, all these great musicians in Austin started coming out: Greg Izor, Oscher's bassist Sarah Brown, and others crowding the front tables. Some jammed on invitation at set's end, before he would pull the time-honored trick of walking out the front door playing, circling the building, then returning through the back door, aided by a wireless guitar unit and microphone. Walter Daniels, the Austinite who brought his own take on blues harp to garage punk, discovered the residency and hipped the local punk crowd. Eventually, the place started getting truly packed. Before the Manchaca Railroad Bar-B-Que closed in April, his live one-man history of the blues made it the place to be on a Tuesday night.

Look What You've Done

Back on the porch at Sam's, Oscher imparts wisdom on Walter Daniels. A lifetime in the blues has changed him from the student to the teacher.

"There was no such thing as formal anything," he offers in response to a question about whether Muddy Waters or his bandmates gave anybody lessons. "I would just say, 'Snake, how'd you make that thing?' 'Easy. Just like this!' Bompa-bompa-bompa-bompa. And he'd show me where his fingers went. That was it. Not formal anything, but it was better than taking music lessons. Because you're learning the sounds and the actions. There's nothing in between, like notes. You're going right straight to the thing. That's the way they learned – same way."

Asked to give capsule impressions of the many legends he played with, Oscher frequently says: "That's book stuff." He's been working on his memoirs for a while, determined to finish the manuscript before year's end. Today, he's more open to offering advice to young harp players.

"Keep that harp in your pocket all the time, keep fighting it, and try to get a sound in your head. Listen to all the great blues harmonica players, and hang out with musicians that are better than you. For intermediate harmonica players? Just crystallize that tone that you're looking for, and keep fighting that harp. And for advanced harmonica players? Don't try to outplay your peers. Just try to outplay yourself."

Paul Oscher headlines at C-Boy's on South Congress Friday, June 27, and Saturday, June 28.