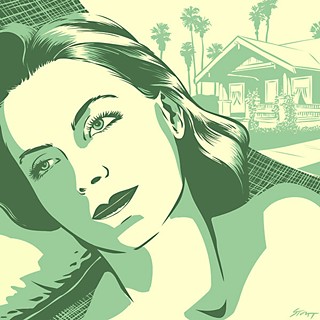

Letters at 3AM: In Greta Garbo's Bungalow

As beautiful as Greta Garbo was, she was something more

By Michael Ventura, Fri., Nov. 1, 2013

This happens and that happens and you wind up spending the night somewhere unexpected. How I arrived at Greta Garbo's bungalow is a noisy story of little interest, but picture a rich house on a slope high above the Pacific, with a walkway down to a long oval pool flanked on its landward side by tidy bungalows with doors that open to a view of the sea below. One of those prim little rooms had been a special favorite of Greta Garbo's.

My hosts related how Greta Garbo and John Gilbert (or was it that symphonic conductor?) came here in the Twenties (or was it the Thirties?) to escape the attentions of the press. Seems Garbo preferred the bungalow's slim bed to the plusher accommodations of the main house. I was told stories varnished by repetitive recitals and proven, if memory serves, by a photo in the dining room or sitting room or reading room or breakfast room or one of the many other rooms.

My hosts wished me a good sleep and left me to myself. The lights were lit in the pool. The sky – I don't remember what sort of sky it was. The sea sounded just like the sea. It was about 11 at night, very early for me – sleep wouldn't be possible for hours.

Greta Garbo? Honestly? Here? It's more fun if it's true, so let's believe it.

A chill from the sea, Irish whiskey in a tumbler, a cigarette, an improvised ashtray, a folding chair, and, in a way, Greta Garbo.

In 1926 Greta Garbo was younger than her century – not yet 21 when Flesh and the Devil went into production. How did someone so young project such sensual, thoughtful authority? She hadn't decades of movies to imitate; she was originating. No tricks. Few gestures – surprisingly few. But her face – most faces are empty, flat screens by comparison. Hers was a face of such flexible, precise expression that directors held her close-ups longer than anyone else's, because something was always happening in a Garbo close-up, even if she seemed perfectly still.

She hinted once at the source of her power: "It's not just scenes that I'm doing. I'm living."

As beautiful as she was, she was something more: She was very strange, and had the air of having accepted her strangeness without equivocation.

Director Clarence Brown said, "Many times I was never quite satisfied after two or three or four takes, [but] I would go ahead and [print them] anyway. But when that scene was shown on the screen, it had something you couldn't see on the set."

This had nothing to do with costumes or lighting or how she neither wore bras nor bound her breasts (as was often the practice in early cinema). Brown said it was "something behind the eyes that told the whole story."

The camera saw in Garbo what could not be seen by other means. It was really as though she existed in different realms. Her friend, the actress Eleanor Boardman, said, "She was man, woman, and child – you can't pigeonhole Garbo."

So when she hung out at this pool, smoking absently, pacing that languid stride, unself-consciously naked – as friends said she often was, no matter if butlers or gardeners were about – even then you might not see her truly.

Twenty years old, shooting Flesh and the Devil, she looks with mocking tenderness at John Gilbert, eight years her senior, and says something we don't hear, then the title card comes on: "You are very young." You buy completely her authority to say it. Her presence made everyone around her seem younger, because of what the camera saw in Garbo – something ancient that resists modern vocabularies.

Her bungalow's interior was simplicity itself and well-preserved, almost like an exhibit, including the old books on shelves high off the floor – and now came disbelief, for it was easier to believe this was Greta Garbo's bungalow than to believe that I held in my hands a first edition of Henry Adams' Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres.

The pages hadn't been cut.

Until about a century ago, bookbinders connected pages at the edges; a reader didn't just turn a page, the page had to be cut – usually with a small, polite-looking knife.

My dear God – my dear Garbo! – did I hold the privately printed 1904 edition or the first public edition of 1913? Either way, it had gone the better part of a century unread and unheeded in this bungalow. I doubted my hosts knew of its existence.

I decided not to tell them.

This book meant so much to me – I didn't need to cut a page to recite:

"Truth, indeed, may not exist; science avers it to be only a relation; but what men took for truth stares one everywhere in the eye and begs for sympathy."

Since I'd read that years before, the sentence had said itself to me at least a couple of times a month.

I took the book outside, sat, sipped some whiskey, lit a cigarette, said the sentence softly several times – then thought incongruously of Garbo saying, "I have been smoking since I was a small boy." Her friends reported that it was the kind of thing she'd say, like, "Give an old man a cup of tea," meaning herself.

It occurred to me that my hosts would certainly be interested to know the book's likely value. The 1904 edition (as I suspected this was, because of its size) surely was worth $10,000 or even $15,000. The 1913 – $5,000? More? Uncut pages, after all.

No, I would not tell them.

Some discoveries should be made all on one's own.

Truth indeed may not exist ... stares one everywhere in the eye ... begs for sympathy.

Greta Garbo and Henry Adams are not such an odd couple. She seemed always to be slightly distracted by something we wouldn't understand and he wrote of himself in the third person, as though always watching himself, while attempting to contain the pain of his intellectual turmoil with a grand calm and soothing prose that was, completely, a mask and a pose. In his greatest work, The Education of Henry Adams, he concluded that "Evidently the new American [you and me] would have to think in contradictions, and ... the new universe would know no law that could not be proved by its anti-law."

Adams gave good reasons for expecting that the 20th century would release increasingly chaotic energies that he feared might be beyond humanity's control. Also in The Education, he regretted that American art was "sexless," that "an American Venus would never dare exist," and that "in America neither Venus nor Virgin ever had value as force – at most as sentiment."

So Adams would have been delighted or driven mad – probably both – when the chthonic powers of technology unleashed nothing less than Greta Garbo's perfect embodiment of Aphrodite as she exists in Sappho's poem (Anne Carson's translation): "Deathless Aphrodite of the spangled mind." Garbo – impenetrably strange, a woman, a force, who always changed the story but ("deathless") whom the story never changed.

Strange and wondrous, to have met them both, Henry Adams and Greta Garbo, in this odd way on this odd night at this odd place. Light another cigarette, pour another splash, and remember how, in Flesh and the Devil, we see John Gilbert say, "Who ... are ... you?" A title card confirms it, with ellipses. Garbo looks at him from a vast but kind distance and says with her equivocal smile what a title card translates as: "What does it matter?"