Endangered Species Conservation

'The Last Unicorn' takes a victory lap at the Alamo Drafthouse

By Amy Gentry, Fri., May 31, 2013

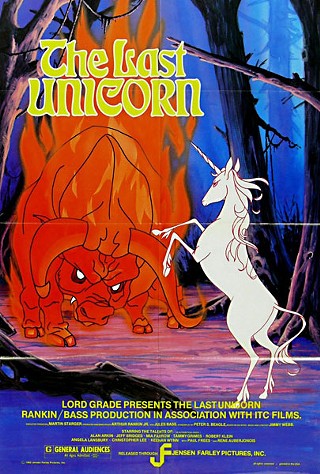

"Don't you want to try something else?" Throughout the 1980s, this chorus rang out from video stores across America as parents watched their daughters reach for a VHS tape with a vaguely menacing cover of a unicorn battling a fiery red bull. Despite their protestations, The Last Unicorn was the repeat rental of choice for a generation of bookish, introverted young girls. I should know; I was one of them.

So was Alamo Drafthouse programmer Sarah Pitre. "When I was a kid, my mom would take me to the video store once a week to pick out a few movies," she says. "Without fail, I would always rent The Last Unicorn. My mom was understandably perplexed. I'd seen it at least 20 times, not to mention that a few scenes scared the living daylights out of me."

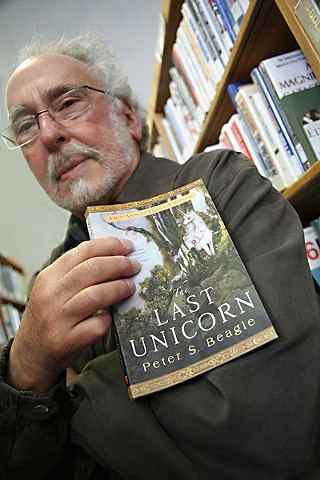

Three screenings of the film at the Alamo Drafthouse will not only give fans a chance to relive their childhoods, but also convince newcomers that the 1982 animated film from production house Rankin/Bass (founded by directors Arthur Rankin and Jules Bass) is more than just nostalgic 1980s kitsch. The new digital print features crisper, brighter animation and restores original dialogue excised from DVD versions of the film. Even more exciting for die-hard fans, Peter S. Beagle, who adapted the film's screenplay from his own 1968 novel and whom Neil Gaiman calls "the gold standard of fantasy," will be present to answer questions before the film.

What sets The Last Unicorn apart from its animated brethren? Well, for starters, there's the dark, moody plot, infused with Beagle's wry, deadpan humor and laced with melancholic themes of mortality and regret. Upon discovering that she's the last of her kind, a lone unicorn (voiced by Mia Farrow) sets out to find the rest of her kin, undergoing a startling transformation into a human woman at the height of her quest. Along the way, she encounters a series of ghoulish and grotesque characters, including a mad king (Christopher Lee), his demonic minion bull, a snickering skeleton (Rene Auberjonois), an evil carnival witch (Angela Lansbury), and a bloodthirsty, triple-breasted harpy – not exactly kiddie fare. Its shape-shifting love story owes more to Greek myth than to The Little Mermaid; in the end, the unicorn gives up love, along with her human shape, to save her people. It's Casablanca for fourth graders, with Ingrid Bergman recast as the hero.

There's also the unusually strong cast of voice actors, which includes Alan Arkin and Jeff Bridges in addition to Lee, Farrow, and Lansbury. In an interview with The Austin Chronicle, Beagle explained how the film wound up with such an enviable cast. "Most of them knew the book, and that made a lot of difference," he says. Bridges reputedly offered to do the part for free out of love for the book, and venerable fantasy aficionado Lee once named the Beagle novel as one of his top two desert-island picks (the other being The Lord of the Rings). Beagle remembers the first time he met Lee: "He had just recorded King Haggard's speech about the first time he ever saw unicorns. I told him that he had recorded my favorite speech in the book, and he immediately offered, in this grand Christopher Lee style, to re-record it if I didn't like it. 'We're right here in the studio, I can tape it again if you like.' And of course he'd done it perfectly."

The film's animation is remarkably sophisticated as well, especially given the budget constraints of the Rankin/Bass production studio. Producer Michael Chase Walker had pitched the film to Disney, Warner Bros., and a succession of other major animation studios, but, despite interest from individual animators, the story was too dark and too quirky to be considered a good box-office risk at a time when many studios were backing away from features to concentrate on the safer television market. "The film was always almost getting made," says Beagle. When he learned that the film had been signed with Rankin/Bass, best known at the time for producing stop-motion holiday specials like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and The Year Without a Santa Claus, he was furious. "I remember screaming, 'Why didn't you just go all the way and sell it to Hanna-Barbera?' And Michael looked immensely sad and said, 'They were next.'"

Surprisingly, the animation studio of last resort proved to be a perfect fit for the idiosyncratic screenplay. Like all Rankin/Bass productions, the film was animated by the Japanese studio Topcraft, whose major animators, including studio head Toru Hara, went on to work on the highly regarded Hayao Miyazaki features Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and My Neighbor Totoro. The film's animation aesthetic resembles the Studio Ghibli style: Alternately graceful and grotesque, Lady Amalthea's furtive movements, eerily enlarged eyes, and delicate limbs link her visually with her unicorn alter ego. The film's richly painted backgrounds borrow from medieval tapestries, and Janet Maslin called the film's climactic animation sequence "startling and lovely" in her 1982 New York Times review. In one particular standout chase sequence, the Red Bull was animated "in ones," meaning that a new image was drawn for each frame, rather than every other frame. The resulting fluidity and vibrancy of the moving image may explain why those who watched the film as children always remember the Red Bull so vividly. According to Beagle, "While children are terrified by the Red Bull, they remember the Red Bull; they come back to see it and be scared again."

One final aspect of the film that sticks with fans is its music. Rather than using their in-house music team, Rankin/Bass hired experienced songwriter Jimmy Webb, whose catalog included hits like "Up, Up and Away" and "MacArthur Park," to write original songs for the score, which was performed by 1970s folk-rock group America. Moreover, in a practice that is more or less unheard-of in commercial animated features, the film was scored before it was animated, meaning that the flow of images was created to follow the music rather than the other way around. This gives the film a peculiarly dreamlike quality. According to Beagle, himself a musician, Webb has written that The Last Unicorn was his best experience working on a film. "It opened his work up to an entirely new audience of 7-year-old girls."

Even fans who grew up with an appreciation for these aspects of the movie, however, may not know its troubled history – or the fact that for three decades after the film's release, Beagle made not a dime in royalties from the film's theatrical, VHS, and DVD releases. The film was plagued with difficulties from its inception. First, the film had difficulties finding a distributor, then the small distribution company that accepted the film, Jensen Farley, folded just 17 days after the film's theatrical release. In those 17 days, the film earned $6.5 million at the box office; there is no way of knowing how much the theatrical release actually grossed, since private theatre owners undoubtedly kept running the film and pocketing the profits long after the distributor's demise. For 20 years, the film floated around on VHS released by British company ITC, which had acquired the film with 90 others in the type of batch deal often used to get around paying royalties.

Then, in 2004, there was the disastrous DVD release: a shoddy, fourth-generation transfer saddled with childish, oversimplified cover art that Beagle's business manager Connor Cochran describes as "My Little Pony on steroids." Soon Wal-Mart, which stocked the movie at its checkout line, started getting phone calls from mothers who had picked up the DVD for very young children based on the misleading cover art. They were particularly disturbed by three uses of the word "damn," which Wal-Mart obligingly pressured Lionsgate Films, the new distributor, to chop out of the soundtrack. All subsequent releases of the film have kept the sanitized soundtrack in place; only a 2011 Blu-ray release offers a choice between the original and the doctored version.

During these 30 years of crooked deals, corporate neglect, and plain bad luck, Beagle's only earnings from the film besides an initial screenwriting fee came from overseas video releases, which amounted to less than $4,000. When Cochran met Beagle in 2001, the author was in severe financial distress, about to lose his house to foreclosure and, as Cochran puts it, "six weeks away from being homeless and almost penniless." Cochran began a decadelong fight to secure royalties for Beagle's work, and in 2011 Beagle finally began to earn money from the film, along with some remunerations for the preceding years.

Perhaps just as importantly, Cochran began dragging Beagle to conventions, where Beagle made an amazing discovery. For years he had assumed that his book and film, though moderate successes in their time, had been largely forgotten. "Peter kept track the way most writers keep track of their work, which is by the royalty checks," Cochran explains. "The checks were not large, or in some cases existent, so he just assumed that it wasn't selling." This, as millions of fantasy readers, anime enthusiasts, and grownup girl-nerds can attest, was not the case. Beagle still sounds reverent when he talks about going to the 2011 New York Comic Con. "I met – I always feel embarrassed by this word – I met my fan base. I realized I had one."

Beagle's fan base has always been strong in Austin. In fact, the first contemporary screening of The Last Unicorn Beagle attended was at the Alamo Drafthouse Lake Creek in October 2009. He was overwhelmed with the positive response from locals who bought out both the first show and an added-on second show. The feeling is mutual; Beagle calls the Drafthouse "the only civilized way to watch movies." Now embarking on a cross-country tour with the film, Beagle and Cochran hope to introduce a new generation of fans to the film.

Asked about why the film continues to have such an impact, Beagle speculates: "There's a lingering quality that I think it has. The fact that it's a bittersweet sort of ending, which is the way I tend to work, stays with people. A lot of people come to me to talk about the ending, wishing there could be a perfectly happy ending but realizing that it can't be."

With long-delayed financial restitution, a taste of public recognition, and the accumulated love of a generation of fans, The Last Unicorn is getting something as close to a "perfectly happy ending" as such things can get. The only thing that could make it sweeter is a whole new chorus of children's voices begging their parents to rent it just one more time.

The Last Unicorn will screen at the Alamo Drafthouse at the Ritz on Sunday, June 2, at 1pm; Monday, June 3, at 7pm at the Village location; and Tuesday, June 4, at 7pm at Lake Creek. All screenings will be preceded by a Q&A session with screenwriter Peter Beagle.